Top 10 Fascinating facts about the Ancient Persian Empire

The Persian Empire, which is regarded as one of the most powerful and important civilizations of all time, was a significant center in the area. Even though ... read more...archaeology has only partially illuminated this vast empire, several excavations and research have produced some intriguing. Here is a list of some of the most fascinating facts about the Ancient Persian Empire.

-

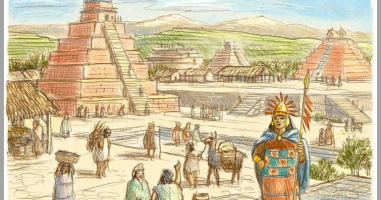

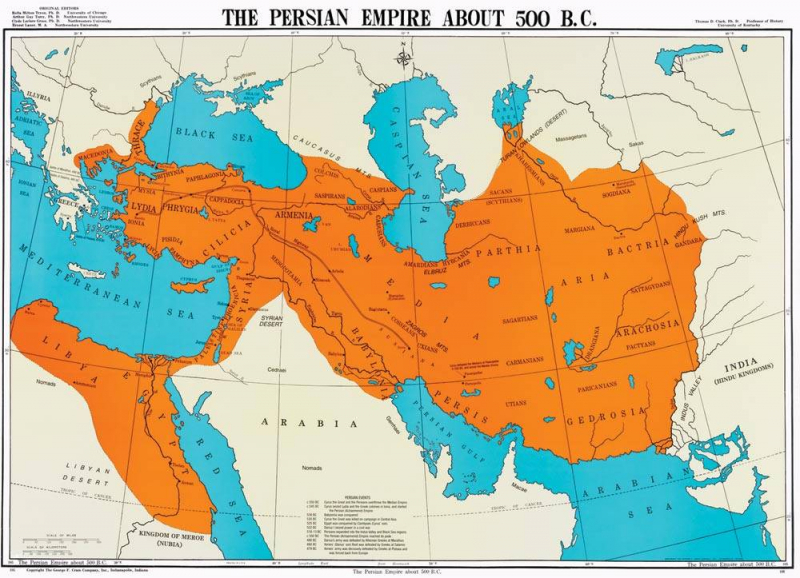

Cyrus the Great founded the Achaemenid Empire, also known as the First Persian Empire, in 550 BC. The empire supposedly stretched across a territory of around 5.5 million square kilometers, from the Balkans in the west to the Indus Valley in the east. This kingdom stood out from the others due to its welcoming of individuals of many backgrounds and religions. People were free to practice their faith without facing prejudice, and this tolerance drew many new residents from the neighborhood. During this time, other kingdoms did not provide such independence.

Several prosperous empires followed the demise of the Achaemenid Empire, most notably the Parthian and Sasanian empires. Arsaces I of Parthia, the head of the Parni tribe, established the Parthian Empire, which existed from 247 BC until 224 AD. The empire was a great political and cultural force under the Parthians. The Sasanian Empire was the final great Persian empire before the Islamic conquests altered Persia's landscape in the seventh century. Following the downfall of the Parthians, they came to power and ruled until 651 AD. The Sasanian civilization served as the foundation for many early Islamic artistic styles.

irantours24.com See U in History / Mythology - youtube.com -

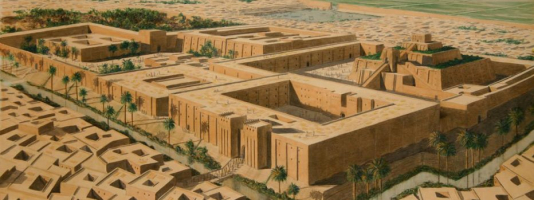

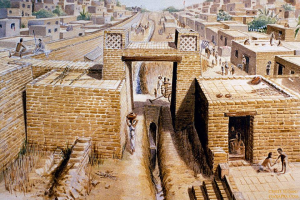

The best of Persian architecture and design may be found in its gardens. In a primarily desert region, when the summers were scorching and the winters were freezing, these lovely and complex gardens were created to offer solace from the harsh weather. The oldest and maybe most magnificent example of a Persian garden can be seen in Pasargadae, the initial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. David Stronach, a specialist in the study of ancient and medieval Iran and Iraq, unearthed the gardens at Pasargadae.

Gardens of Persia were locations for social meetings and leisure time for the Persians and were bordered by exotic plants, orchids, and water channels. Stone-lined streams in rectangular patterns could be seen inside the gardens, and mud-brick walls protected the entire area. The term "paradise" is derived from the ancient Persian phrase "a wall around," which suggests that it was once used to designate a closed-off area. The gardens were undoubtedly a paradise and an oasis in their day. Following the Islamic conquests, these gardens' design ideas were combined with Islamic architecture to produce traditional Islamic gardens. However, due to their fragility, mud-brick gardens require a lot of upkeep, and as a result, very few gardens have endured.

The Persian Gardens - www.reddit.com kathkath303 - youtube.com -

The Declaration of Independence, which was issued in 1776, granted citizens certain unalienable rights from birth. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was written in 1789 during the French Revolution and was founded on similar ideas. Human rights were first recognized in the modern era on these two occasions, however, the Persian Empire had enacted a charter of rights 2,000 years before.

There is no disputing that Persian women had more rights and privileges than women in any other ancient culture, except Egypt. This is true even though the claim that the Persians were the first to issue a Declaration of Human Rights (via the famous Cyrus Cylinder) has been contested. According to the Fortification and Treasury Texts from the reign of Darius I, royal ladies were shown the highest degree of deference. At the same time, men and women of the lower classes performed the same tasks for the same compensation (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE). Women may manage male employees, and those with remarkable abilities and authority were referred to as Arashshara (Great Chief). Women were allowed to be landowners, officers, and senior command in the king's company, as well as to have their enterprises. The most well-liked deity in Early Iranian religion was Anahita, who was still revered as a manifestation of Ahura Mazda after Persians converted to Zoroastrianism's monotheism.

Cyrus the Great wished for religious freedom and equality for all citizens of his realm. In 1879, a piece artifact known as the Cyrus Cylinder was discovered among the ruins of Babylon. It was composed of baked clay and was 22.5 centimeters (8.85 inches) in length. The cylinder has Cyrus's ideas of ethnic, linguistic, and religious freedom etched on it. It also demonstrates his kindness to the Babylonians, whom he vanquished to create his kingdom in 539 BC. Although he has been praised for helping the populace and enhancing their quality of life, some detractors contend that the cylinder glorified the great monarch and that his activities were more intended to please the gods than to benefit his subjects. However, there is unanimity among archaeologists and historians that the item is a stunning illustration of Persian history.

Declaration of Human Rights - www.youthforhumanrights.org

Cyrus Cylinder - en.wikipedia.org -

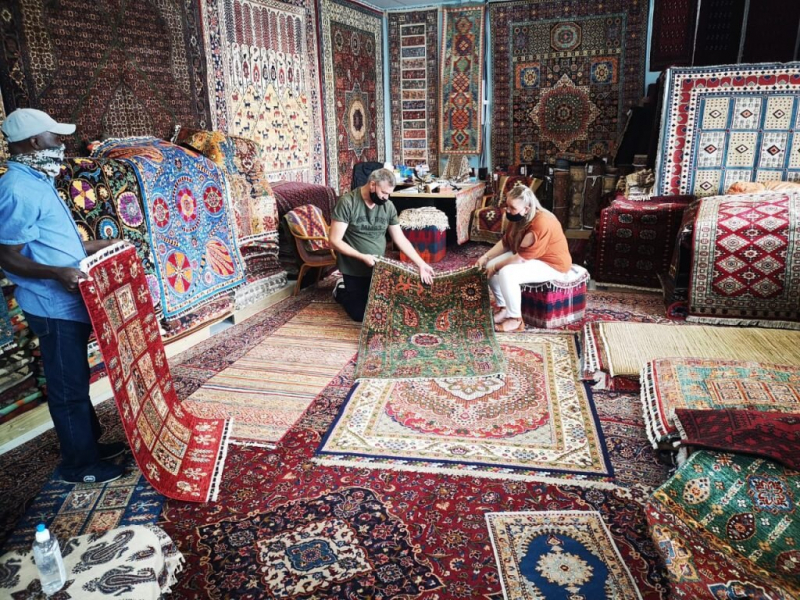

The Persians frequently experienced severe weather, particularly in the winter. The Persian tribesmen, who were primarily nomadic, wove carpets and rugs as a need to combat the cold. These rugs developed into an art form as the empire expanded and trade increased. The carpets became well-liked due to their adaptable designs and patterns, and they quickly became a significant export.

The art of producing carpets is thought to have begun some 2,500 years ago, and with each conquest or invasion, the design of the carpets and rugs evolved. Cyrus the Great had his tomb at Pasargadae in Persepolis covered in carpets and rugs because he was so moved by the exquisiteness of the designs and patterns on the carpets.

The Altai Mountains in Siberia are where the oldest carpet known to man was found. The carpet was preserved by Siberia's icy landscape, and it reveals the talents of earlier civilizations. The carpet's patterns demonstrate how carpet weaving has advanced beyond straightforward patterns. The rug is currently on display in St. Petersburg's Hermitage Museum.

www.rugsoflondon.com

www.rugsoflondon.com -

It is generally accepted that Old Persian was the language of communication during the Achaemenid Empire. The Zoroastrian scripts and scrolls were written in an Old Persian dialect that shared characteristics with Sanskrit and Avestan. However, the regional tongue transitioned to Middle Persian, often known as Pahlavi, after the Achaemenid Empire was overthrown.

Even though Pahlavi was commonly spoken in the province of Pars, relatively few works of Pahlavi literature still exist. The ability to speak Arabic became vital after the Arab conquest, but Pahlavi was still widely used locally. The dialect known as Pahlavi then developed into Modern Persian or Farsi. It is written using the Cyrillic script in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, but it is known as Dari in Afghanistan. Persian poetry is known as ghazals. The introductions to these poems, which frequently exalt wine, love, and nature, are their most crucial components. At ceremonial events and festivals, this kind of poetry was frequently utilized.

Saddleback Persian - youtube.com Langfocus - youtube.com -

Persian boys, who generally belonged to the upper class, were prepared for combat until they were 20 years old, according to the Greek historian Herodotus. However, Strabo, a different historian, claims that all men, regardless of status, received military training that lasted until they were 24 years old. Strabo also notes that the son of an aristocratic commander typically oversaw companies of 50 men. In both peace and conflict, every soldier would remain enlisted in the Persian National Army until age 50.

According to Xenophon, a different Greek philosopher, the Persian army numbered 120,000 Persian warriors in all. Herodotus, a Greek philosopher, also records that the Persian army had a spotless look, with every soldier wearing the same uniform, which was unusual in ancient times. It's thought that Cyrus II gave capes to officials in lesser positions as well as to nobility. The capes were constructed of the finest material and available in a variety of hues, including dark red, crimson, and purple. The capes are believed to have been worn by the troops to keep their appearances consistent.

The Persian army's troops were organized into regiments of 1,000 soldiers or hazaraba. The baivaraba, which consisted of a total of 10 hazaraba, served as the king's royal guards. They also went by the moniker amrataka, which means "immortal" in Sanskrit. This was because there will always be 10,000 soldiers. If a soldier became sick or got hurt, he was replaced right away by a healthy applicant. Finally, Herodotus claims that the baivaraba wore exquisite armor and apparel. The troops' attire included finely woven tunics and pants, which were covered in a coat of mail that resembled fish scales. The warriors also wore gold jewelry. They possessed wooden shields for defense, tiny spears, small swords, stiff bows with cane arrows, and armor. In carriages loaded with provisions including food, clothing, and other necessities, their wives and servants traveled everywhere with them.

www.history.com The Infographics Show - youtube.com -

The literary motif of fatalism is seen in "The brief sum of life refuses us the hope of lasting long", which originated in the Zoroastrian sect known as Zorvanism, which is another Persian creation that is sometimes neglected. Since one could not use the time to alter one's fate in any manner, Zurvan was revered as the God of Infinite Time in Zorvanism, and this religious system gave rise to the idea of fatalism. No matter what one accomplished, they would eventually perish, and their life expectancy was predetermined.

The Persian poet Omar Khayyam (c. 1048–1131 CE) prominently used this theme in The Rubaiyat, although it was first employed by Ferdowsi (c. 940–1020 CE) in his Shahnameh. It was then adopted by Greek and Roman writers, and it is being used today. Though it has served as the inspiration for many works of literature, the motif is probably best encapsulated in the lines "They are not long, the days of wine and roses/Out of a misty dream/Our path emerges for a while, then closes/Within a dream" by the English poet Ernest Dowson.

The Rubaiyat - www.kobo.com

Shahnameh - amazon.com -

The Persian cultural ideal of expressing the truth and believing it was right was one component that helped to foster this tolerance. The Persian word for truth (asa or arta) occurs in many Persian names, especially those of monarchs like Artaxerxes, demonstrating how important truth was to Persian society. The truth was also one of the oaths that soldiers made upon joining the military. Persians hated liars and ridiculed people who were in debt since a debtor was likely to lie to avoid paying back what was due, according to Greek writers who are occasionally if not frequently antagonistic to Persian principles.

The House of Lies, the Persian name for hell, had three levels, the lowest and darkest of which was reserved for the worst of sinners those who, among other sins, had lied the most. They had no desire to force their religion on anybody else since they were confident that it was real and that eventually, people would come to accept Zoroastrianism for what it was. If not, it didn't matter much to them since they thought that transgressors' or unbelievers' souls were only tortured in the hereafter for a limited period until Ahura Mazda welcomed them to paradise.

www.tehrantimes.com Abedawn - youtube.com -

The Persians under Darius I established the first fully developed postal system when he ordered the construction of a road network for the convenience of travel and then organized a service wherein horsemen could transport messages between his numerous cities or encampments. These mounted couriers were given opportunities to rest and refuel along the journey, but they were so focused on their task that they didn't stop. "Whatever the weather - it may be snowing, pouring, burning hot, or dark - they never fail to finish their allocated route in the quickest time," writes Herodotus in admiration of the Persian mail service (Histories, VIII.98).

Since 1914 CE, these words have served as the unofficial slogan of the United States Postal Service in a modified version. Beginning under the rule of Shapur I (240–270 CE), who established the Academy of Gundeshapur, a center of learning and culture, the Persians also started the first hospitals. Under the later Sassanian king Kosrau I (r. 531–579 CE), the school accepted physicians and scholars of all ethnicities and became the first teaching hospital in the world.

Chapar-khaneh (ancient post office) - www.tehrantimes.com Icahn School of Medicine - youtube.com -

The skill of animation for amusement, the habit of having dessert after a meal, and the practice of opulent birthday celebrations were all originally developed by the Persians. Birthday festivities began with a festival commemorating the monarch's birth (as they did in other civilizations), but they eventually moved to the nobility and subsequently the lower classes. A cake with lit candles was offered after the dinner as part of these celebrations, which also featured special dishes made for the honored guest. Animation may have been used as entertainment, as shown by artifacts like a cup that, when quickly turned, depicted a goat leaping in the air to snag leaves from a tree. Music may have also included vocals accompanied by stringed instruments like the carter (also known as the tar) and the sestar, a precursor to the modern guitar. Dessert was often offered as the final course of every dinner, not only on special occasions like birthdays.

Although the cake itself may have been made especially for the occasion, it was customary for people to follow dinner with dessert or some type of treat. The Persians felt the Greeks were savage and illiterate for not realizing the worth of sweets and thought them uncultured and underfed whereas the Greek authors chastised the Persians for this habit. The celebration of a birthday and the idea of dessert both emphasize the importance of enjoyment in Persian culture.

www.thedailymeal.com Learn Persian with Chai and Conversation - youtube.com