Top 8 Interesting Facts About Lusitania And Its 1915 Sinking

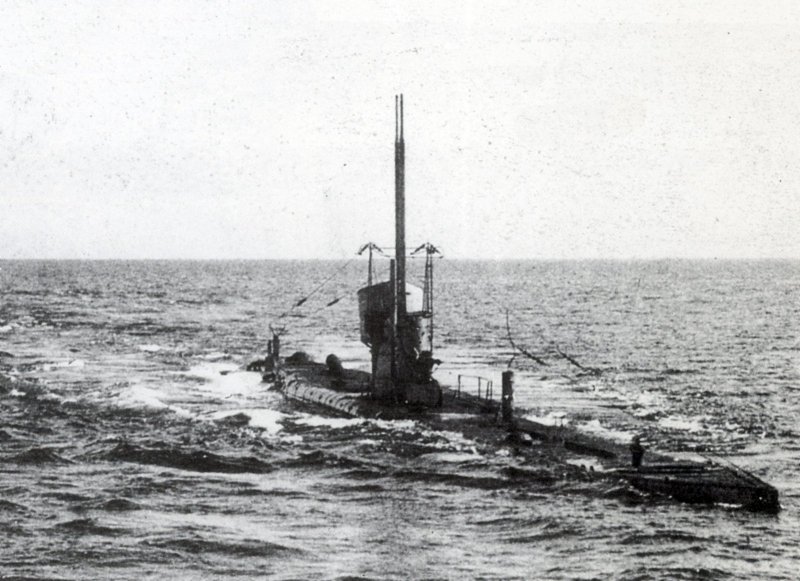

The RMS Lusitania was a British-registered ocean liner that was destroyed by an Imperial German Navy U-boat on 7 May 1915, about 11 nautical miles (20 ... read more...kilometers) off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland, during World War I. The attack occurred in the declared maritime war zone surrounding the United Kingdom, shortly after unrestricted submarine warfare against British ships. Here are the 8 interesting facts about Lusitania and its 1915 sinking.

-

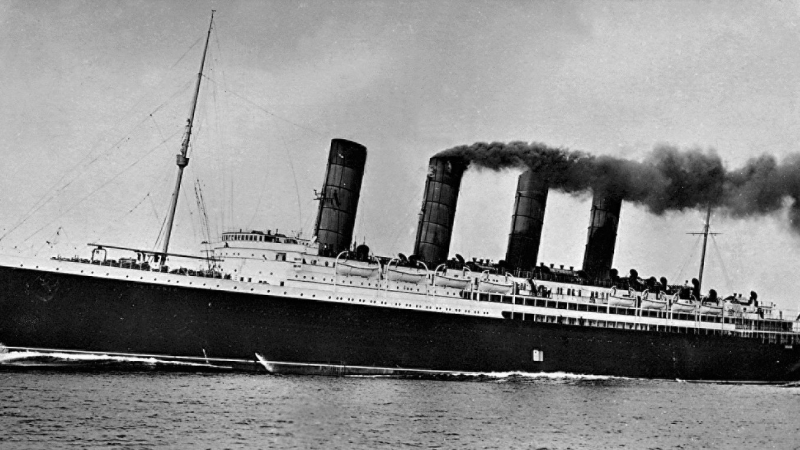

One of the interesting facts about Lusitania and its 1915 sinking is that RMS Lusitania (named after the Roman province in Western Europe that corresponded to modern-day Portugal) was a British ocean liner that was launched in 1906 and won the Blue Riband award for the fastest Atlantic crossing in 1908. It was the world's largest passenger ship for a short time until the Mauretania was completed three months later.

Cunard formed a committee to decide on the new ship's design, with James Bain, Cunard's Marine Superintendent, as its chairman. Rear Admiral H. J. Oram, who worked on ideas for steam turbine-powered ships for the Royal Navy, and Charles Parsons, whose company Parsons Marine was now developing turbine engines, were among the other participants.

Parsons claimed that he could construct engines capable of reaching speeds of 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph), which would necessitate 68,000 shaft horsepower (51,000 kW). The largest turbine sets ever built were 23,000 shp (17,000 kW) for the Dreadnought battleship and 41,000 shp (31,000 kW) for Invincible-class battlecruisers, implying that the engines would be of a new, untested design. Turbines have the advantage of producing less vibration than reciprocating engines and providing higher reliability in high-speed operation while using less fuel. It was decided to conduct an experiment by installing turbines on Carmania, which was already under construction. As a result, the ship is 1.5 knots (2.8 km/h; 1.7 mph) quicker than her conventionally powered sister Caronia with predicted benefits in passenger comfort and operating economy.

The ship made its inaugural trip on September 7, 1907, traveling from Liverpool, England, to New York City. The Lusitania was one of the fastest ships in the world at the time. It earned the Blue Riband for quickest Atlantic crossing the following month, averaging over 24 knots. The Mauretania would eventually win the Blue Riband, and the two ships would compete for it on a regular basis.

thoughtco.com

smithsonianmag.com -

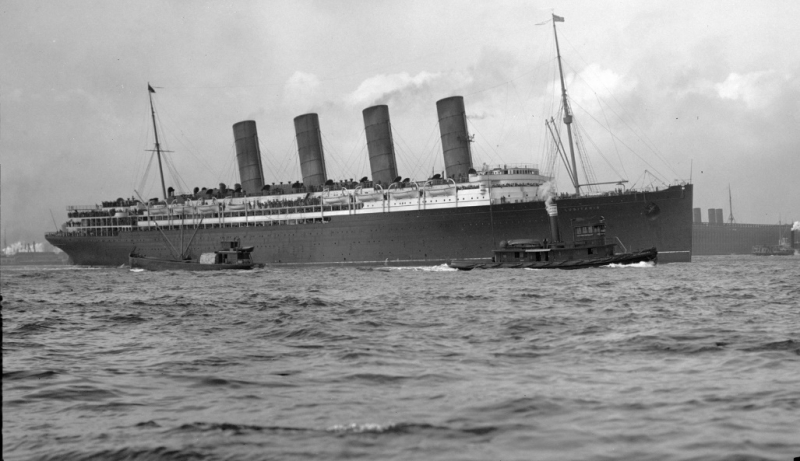

The British government sponsored the building and operation costs of the Lusitania, with the understanding that she could be converted to an Armed Merchant Cruiser if necessary. The British Admiralty considered her for requisition as an armed merchant cruiser at the onset of the First World War, and she was added to the official list of AMCs.

The Lusitania was still a commercial passenger ship in 1915. Because the Admiralty then reversed their decision and decided not to use her as an AMC after all; large liners like the Lusitania consumed massive amounts of coal (910 tons per day, or 37.6 tons per hour) and drained the Admiralty's fuel reserves, so express liners were deemed inappropriate for the role when smaller cruisers would suffice. Because they were also quite distinctive, smaller liners were used instead as transports. Lusitania, like Mauretania, remained on the official AMC list and was included as an auxiliary cruiser in Jane's All the World's Fighting Ships in 1914.

Fears for the safety of the Lusitania and other major liners were high when hostilities broke out. The ship was painted in a dull grey color scheme for her first eastbound crossing after the war began in an attempt to hide her identity and make her more difficult to spot visually. When it was discovered that the German Navy was held in check by the Royal Navy, and their threat to commerce was almost largely eliminated, it appeared that the Atlantic was safe for ships like the Lusitania, assuming that the bookings justified the cost of keeping them in service.

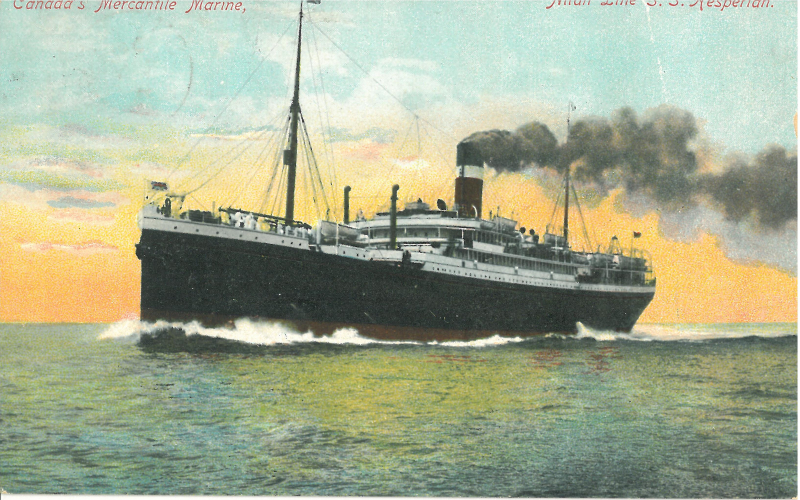

Many of the huge liners were laid up in the autumn and winter of 1914–1915, partly due to dwindling demand for transatlantic passenger travel and partly to safeguard them from mines and other hazards. Some of the most well-known of these liners were converted into troop transports, while others became hospital ships. Despite the fact that bookings on board the Lusitania were not particularly robust throughout that autumn and winter, demand was sufficient to keep her in civilian service. However, cost-cutting measures were implemented.

news.usni.org

fortune.com -

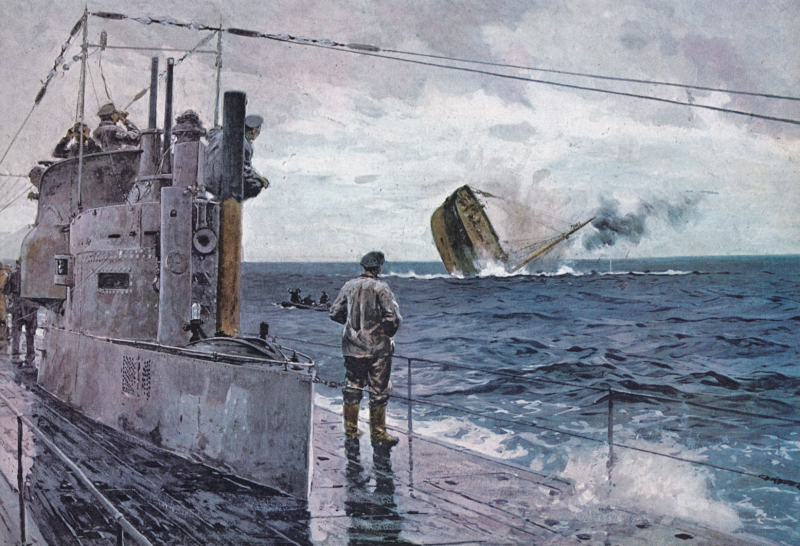

One of the interesting facts about Lusitania and its 1915 sinking is that the seas of the United Kingdom were no longer safe. By early 1915, a new menace had emerged: submarines. Initially, they were exclusively utilized by the Germans to target naval vessels, which they did relatively seldom but with spectacular success. The U-boats then began to target commerce vessels on occasion, almost invariably in conformity with the old Cruiser Rules. As a result of the British declaration of the North Sea as a war zone in November 1914, the German government decided to push up their submarine campaign in order to obtain an advantage on the Atlantic. Germany declared the seas surrounding the United Kingdom and Ireland a war zone on 4 February 1915, declaring that Allied ships in the area would be sunk without warning beginning on 18 February. This was not wholly unfettered submarine warfare, as precautions were taken to avoid sinking neutral ships.

A German U-boat sank the Lusitania 11 miles (18 km) off the southern coast of Ireland, inside the proclaimed war zone, on the afternoon of May 7. The German government justified treating the Lusitania as a naval vessel since she carried 173 tons of war armaments and ammunition, making her a valid military target, and they claimed that British commerce ships had broken cruiser rules from the start of the war. By 1915, the globally recognized cruiser regulations had become obsolete; with the advent of Q-ships by the Royal Navy 1915, which were armed with disguised deck guns, it had become more perilous for submarines to surface and give warning. The Germans claimed that the Lusitania was frequently transporting "war munitions" that she was under Admiralty control, that she could be turned into an armed auxiliary cruiser to join the war, and that her identity had been concealed, and that she flew no flags. They claimed she was a non-neutral vessel operating in a designated war zone, with orders to avoid capture and ram submarines.

There has long been a theory, expressed by historian and former British naval intelligence officer Patrick Beesly, as well as authors Colin Simpson and Donald E. Schmidt, that the British authorities deliberately put the Lusitania in danger in order to entice a U-boat attack and thus drag the US into the war on Britain's side. Winston Churchill wrote to Walter Runciman, President of the Board of Trade, a week before the sinking of the Lusitania, arguing that it is very important to attract neutral shipping to our shores, in the hope especially of embroiling the United States with Germany.

enemyinmirror.com

smithsonianmag.com -

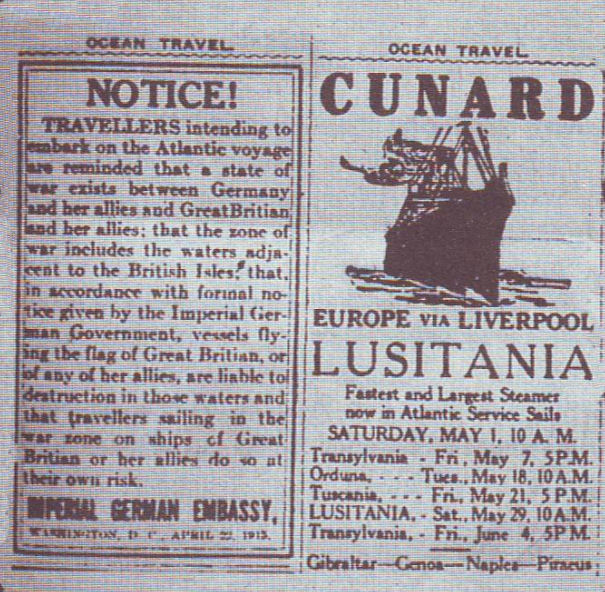

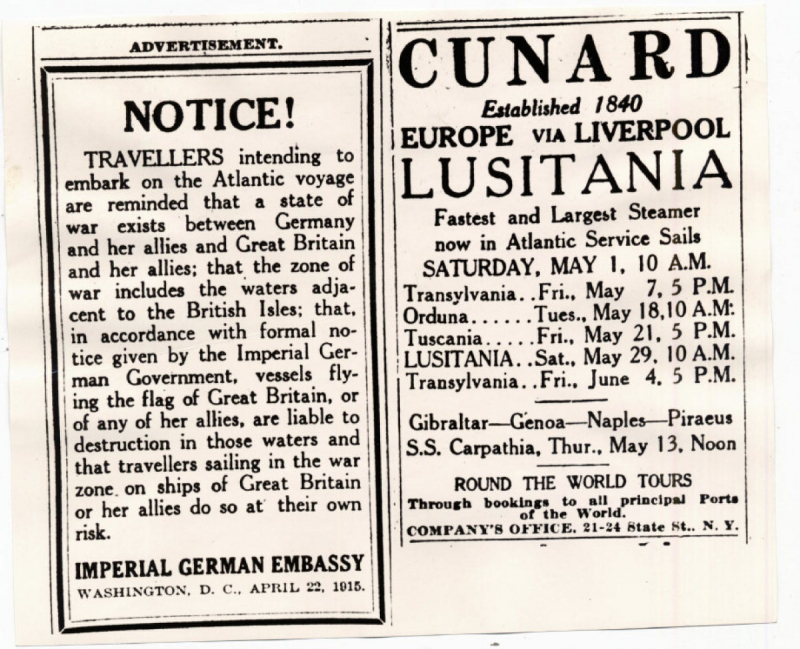

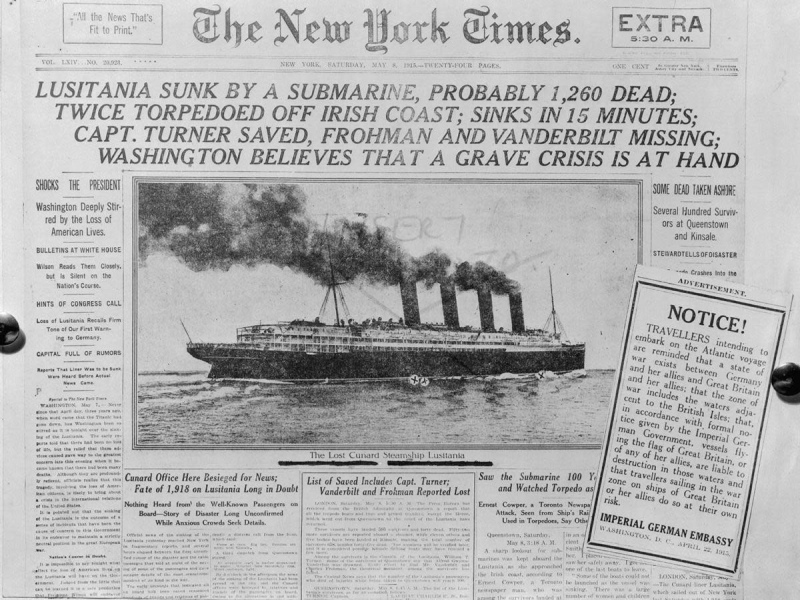

One of the interesting facts about Lusitania and its 1915 sinking is that there was the Imperial German Embassy's official warning concerning traveling before her next crossing. The Lusitania set off from Liverpool on her 201st transatlantic voyage on April 17, 1915, and arrived in New York on April 24, 1915. A group of German–Americans met with a representative of the German Embassy to address their fears about the possibility of a U-boat attack on the Lusitania. The embassy resolved to warn passengers not to board the Lusitania on her next crossing, and on April 22 posted a warning advertisement in 50 American newspapers, including those in New York.

"Travelers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with the formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travelers sailing in the war zone on the ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk."

The Imperial German Embassy's official warning concerning traveling on the Lusitania was posted next to an advertisement for the return journey of the Lusitania. The warning sparked some controversy in the news and alarmed the ship's passengers and crew. However, the Lusitania sailed from New York on May 1, 1915, with 1960 passengers and a load of bullet casings and machine gun cartridges.

greatwarproject.org

thestar.com -

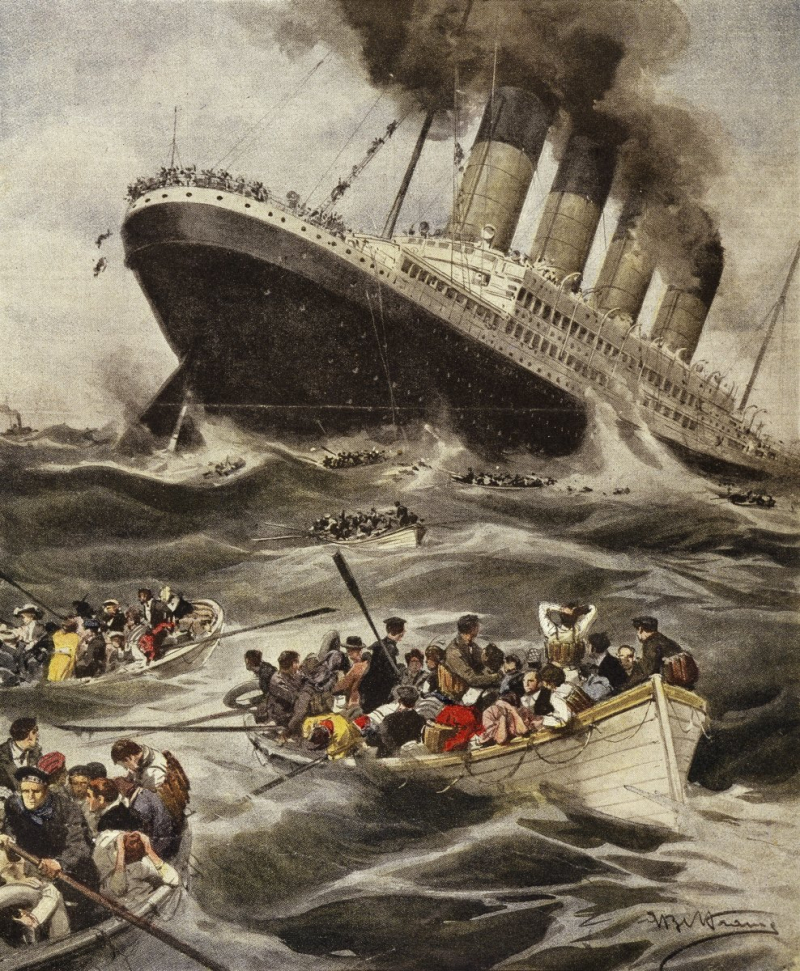

On May 7, 1915, the Lusitania was nearing the end of her 202nd journey from New York to Liverpool and was due to dock at the Prince's Landing Stage later that afternoon. There were 1,266 passengers and 696 crew members on board, for a total of 1,962 people. She was running parallel to Ireland's south coast, about 11 miles (18 kilometers) off the Old Head of Kinsale, when the liner passed in front of U-20 at 2:10 p.m. Because of the liner's high speed, some believe the collision between the German U-boat and the liner was purely coincidental, as U-20 could not have caught the fast vessel otherwise. There are differences in the speed of the Lusitania, which has been claimed to be traveling at less than full speed. The commanding officer of the U-boat, Walther Schwieger, gave the order to fire one torpedo, which impacted the Lusitania on the starboard bow, close beneath the wheelhouse. A second explosion exploded from within the hull of the Lusitania, where the torpedo had struck, and the ship began to founder much more quickly, with a prominent list to starboard.

After RMS Lusitania was struck by a single torpedo, the crew attempted to launch the lifeboats very immediately, but the sinking conditions made their use exceedingly difficult, and in some cases impossible, due to the ship's considerable list. Only six of the 48 lifeboats launched successfully, with numerous others overturning and falling apart. The ship fell down eighteen minutes after the torpedo hit, with the funnels and masts being the last to depart.

The British cruiser HMS Juno, which had only learned of the disaster a few hours before, departed her berth in Cork Harbour to assist. The calamity had spread over the world by the next morning. While the majority of those killed in the sinking were British or Canadians, the deaths of 128 Americans, including writer and publisher Elbert Hubbard, theatrical producer Charles Frohman, multi-millionaire businessman Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, and the president of Newport News Shipbuilding, Albert L. Hopkins, outraged many Americans.

history.com

en.wikipedia.org -

The Lusitania's significant starboard list made launching her lifeboats difficult. The lifeboats on the starboard side swung out too far to step aboard safely ten minutes after the torpedoing when she had slowed enough to begin placing boats in the water. While it was still possible to board the lifeboats on the port side, lowering them posed a new challenge. The hull plates of the Lusitania were riveted, as was customary at the time, and as the lifeboats were lowered, they dragged on the inch-high rivets, threatening to gravely damage the boats before they fell into the ocean.

The Lusitania had 48 lifeboats, more than enough for the entire crew and passengers, but only six were safely lowered, all from the port side. Lifeboat 1 overturned while being lowered, spilling its original occupants into the sea, however it quickly righted itself and was later filled with individuals from the ocean. Lifeboats 9 (5 people on board) and 11 (7 people on board) made it to the water safely, however, both afterward picked up a large number of swimmers. Lifeboats 13 and 15 also made it to the ocean safely, despite being overcrowded with around 150 people. Finally, Lifeboat 21 (with 52 people on board) made it to the ocean and cleared the ship just before the last dive. As she sank, a number of her collapsible lifeboats washed off her decks and offered floatation for some survivors.

Two lifeboats on the port side also cleared the ship. Lifeboat 14 (11 people on board) was safely lowered and launched, but because the boat plug was not in place, it quickly filled with seawater and sank. Later, after removing a rope and one of the ship's "tentacle-like" funnel stays, Lifeboat 2 floated away from the ship with new occupants (its former ones having been spilled into the water when they overturned the boat).

At the time of the sinking, there were 1198 of the 1962 passengers and crew aboard the Lusitania died. In the hours following the sinking, acts of heroism by survivors and Irish rescuers who had heard the Lusitania's distress signals increased the survivor count to 764, three of whom eventually died from injuries incurred during the sinking.

history.com

blog.newspapers.library.in.gov -

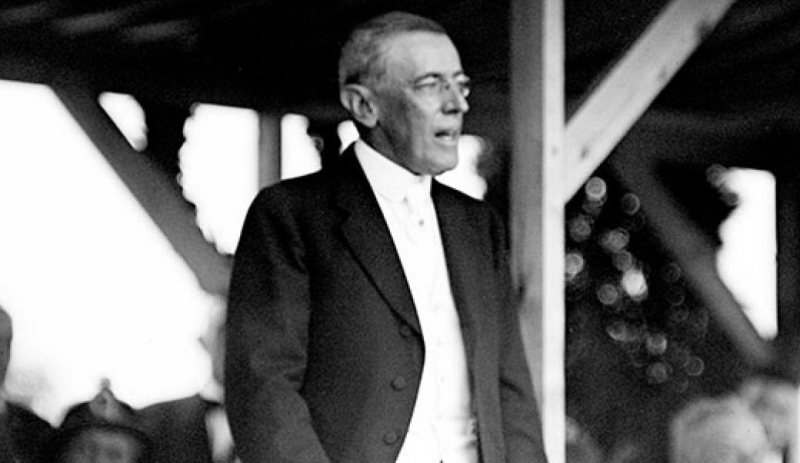

Public opinion in the United States was enraged; war talk was common, and pro-German elements remained silent. The key issue was Germany's harsh refusal to allow passengers to leave on lifeboats, as required by international law. President Woodrow Wilson declined to declare war right away; his primary purpose was to negotiate an end to the war. On May 10, 1915, in Philadelphia, he stated: "There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right."

The subject was hotly contested within the US government in the weeks following the sinking, and communication was exchanged between the US and German governments. German Foreign Minister Von Jagow maintained that the Lusitania was a valid military target because she was described as an armed merchant cruiser, flew neutral flags, and was instructed to ram submarines — a clear violation of the Cruiser Rules.

Von Jagow also claimed that the Lusitania had carried munitions and Allied troops on prior excursions. Wilson insisted that the German government apologize for the sinking, recompense US victims, and agree not to repeat the mistake in the future. Wilson's failure to take more harsh measures disappointed the British. President Wilson was urged by Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan that "ships carrying contraband should be prohibited from carrying passengers ... [I]t would be like putting women and children in front of an army." Bryan resigned later because he believed the Wilson government was biased in ignoring British violations of international law, and that Wilson was pushing the United States into the war.

historyhub.info

history.com -

Dr. Bernhard Dernburg, the former German Colonial Secretary, delivered a speech in Cleveland, Ohio, on May 8, attempting to justify the sinking of the Lusitania. Dernburg was recognized as the Imperial German government's official spokesman in the United States at the time. Dernburg claimed that because the Lusitania "carried contraband of war" and was "classified as an auxiliary cruiser", Germany had the right to destroy her regardless of the passengers on board. Dernburg went on to say that the German Embassy's warnings prior to the ship's departure, as well as the 18 February note stating the presence of "war zones", absolved Germany of any responsibility for the deaths of the American citizens on board. He mentioned the ammunition and military goods declared on the manifest of the Lusitania and stated that "vessels of that kind" might be seized and destroyed under Hague rules without regard for a war zone.

The German government issued an official communication about the sinking the next day, stating that the Cunard liner Lusitania was torpedoed by a German submarine and sank yesterday, that Lusitania was naturally armed with guns, as were recently most of the English mercantile steamers, and that, as is well known here, she carried large quantities of war material. The Collector of the Port of New York, Dudley Field Malone, issued an official denial to the German claims, stating that the Lusitania had been inspected before departure and no guns, mounted or unmounted, were discovered. Malone asserted that no commerce ship would have been permitted to arm and depart the port.

Following the sinking, the German government attempted to explain it by saying in an official statement that the ship was armed with guns and carried huge quantities of military material. They also claimed that because she was classified as an auxiliary cruiser, Germany had the right to destroy her regardless of the number of passengers on board and that the warnings issued by the German Embassy prior to her departure, as well as the 18 February note declaring the existence of "war zones," absolved Germany of any responsibility for the deaths of American citizens aboard. While the Lusitania was constructed with gun mounts as part of government loan conditions during her construction to allow for quick conversion into an Armed Merchant Cruiser (AMC) in the event of a conflict, the guns themselves were never installed. Her cargo was estimated to be 4,200,000 rifle cartridges, 1,250 empty shell cases, and 18 cases of non-explosive fuses, all of which were recorded in her manifest, although the cartridges were not formally classified as ammunition by the Cunard Line.

felixsommerfeld.com

opposite-lock.com