Top 10 Inventions and Achievements of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of Western Asia located in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent along the Tigris-Euphrates river system. Mesopotamia ... read more...now occupies modern Iraq. In a larger sense, the historical territory includes modern-day Iraq and Kuwait, as well as parts of Iran, Syria, and Turkey. From roughly 10,000 BC, Mesopotamia was the site of the initial Neolithic Revolution advancements. It has been linked to some of the most significant advances in human history, such as the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops, and the development of the cursive letter, mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture. It is thought to be one of the world's first civilizations. Here are 10 famous inventions and achievements of Mesopotamia you should know.

-

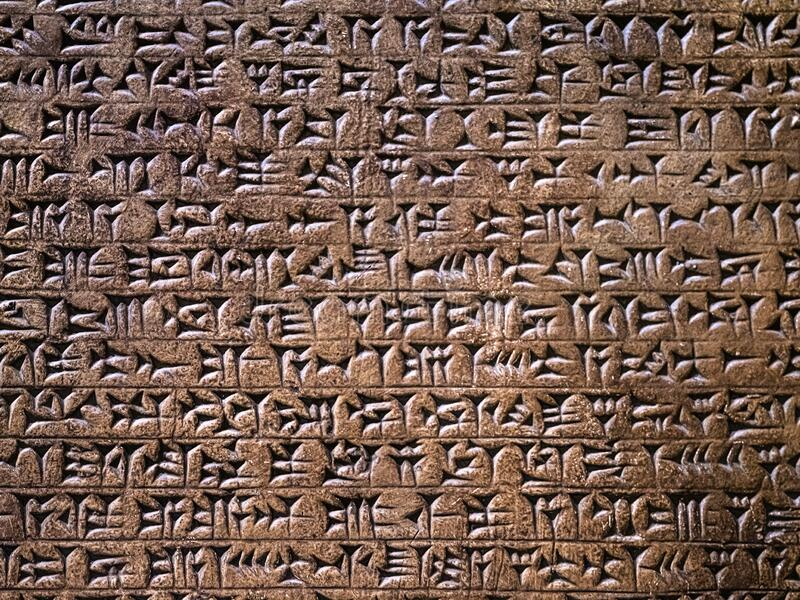

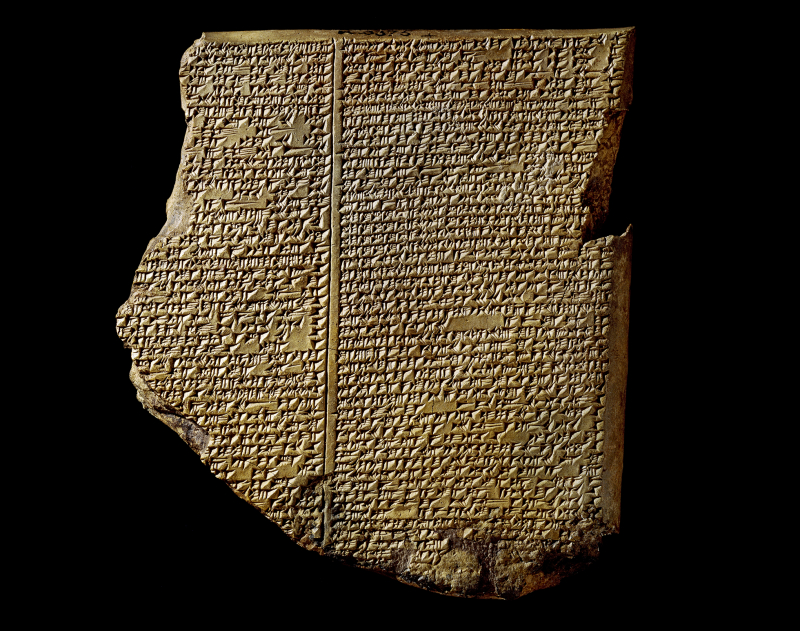

One of the inventions and achievements of Mesopotamia is Cuneiform writing. Cuneiform was established for the Sumerian language early in Mesopotamia's history (about the mid-4th millennium BC). Because of the triangular tip of the stylus used to impress marks on wet clay, cuneiform literally means "wedge-shaped." Each cuneiform sign's standardized form appears to have evolved from pictograms. The earliest texts (7 archaic tablets) are from the É, a temple devoted to the goddess Inanna in Uruk, from a structure designated by excavators as Temple C.

Cuneiform script's early logographic system required many years to master. As a result, only a small number of people were engaged as scribes to be educated in its use. Significant segments of the Mesopotamian population did not become literate until the widespread adoption of a syllabic script was adopted under Sargon's hegemony. Massive text archives were found from the archaeological surroundings of Old Babylonian scribal schools, where literacy was spread.

Sumerian was used as a religious, ceremonial, literary, and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the 1st century AD when Akkadian progressively superseded Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia at the turn of the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC (the exact dating is debatable)

Ancient Cuneiform Writing Script on the Wall -Dreamstime.com

blog.britishmuseum.org -

Babylonian mathematics (also known as Assyro-Babylonian mathematics) is the mathematics produced or performed by the inhabitants of Mesopotamia from the time of the early Sumerians to the decades after Babylon's collapse in 539 BC. The Sumerian culture swiftly distinguished itself from others through the development of mathematics, especially arithmetic and algebra. The sexagesimal (base 60) numeric system was used in Mesopotamian mathematics and science. This is where the 60-minute hour, 24-hour day, and 360-degree circle come from. The Sumerian calendar was lunisolar, with a lunar month divided into three seven-day weeks. This type of mathematics proved useful in the creation of early maps.

The Babylonians also developed theorems for calculating the area of various forms and solids. They calculated the circumference of a circle to be three times the diameter and the area to be one-twelfth the square of the circumference, which is right if remained constant at 3. The volume of a cylinder was calculated as the product of the area of the base and the height; however, the volume of a cone or square pyramid's frustum was calculated improperly as the product of the height and half the total of the bases. In addition, a tablet was discovered recently that was marked as 25/8 (3.125 instead of 3.14159). The Babylonians are also known for the Babylonian mile, a unit of measurement equivalent to approximately seven contemporary miles (11 km). This distance measurement was subsequently changed to a time-mile, which was used to measure the Sun's journey and so represented time.

en.wikipedia.org

britannica.com -

One of the inventions and achievements of Mesopotamia is the wheel. It is a circular component that rotates on an axle bearing. The wheel is one of the six simple machines' fundamental components, along with the wheel and axle. Wheels and axles enable heavy things to be easily moved, aiding movement or transit while bearing a load or doing labor in machines.

From roughly 10,000 BC, Mesopotamia was the site of the initial Neolithic Revolution advancements. It is credited for inspiring some of the most significant developments in human history, such as the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops, and the development of the cursive script, mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture. It is thought to be one of the world's first civilizations.

The location and timing of the development of the wheel are unknown because the earliest hints do not ensure the existence of true wheeled transport or are too widely scattered. The wheel is said to have been invented by Mesopotamian culture. The wheel, however, unlike previous game-changing discoveries, cannot be assigned to a single or multiple inventors. Early evidence of wheeled cart use has been discovered in the Middle East, Europe, Eastern Europe, India, and China.

idesign.wiki

oi-idb.uchicago.edu -

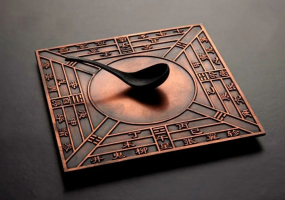

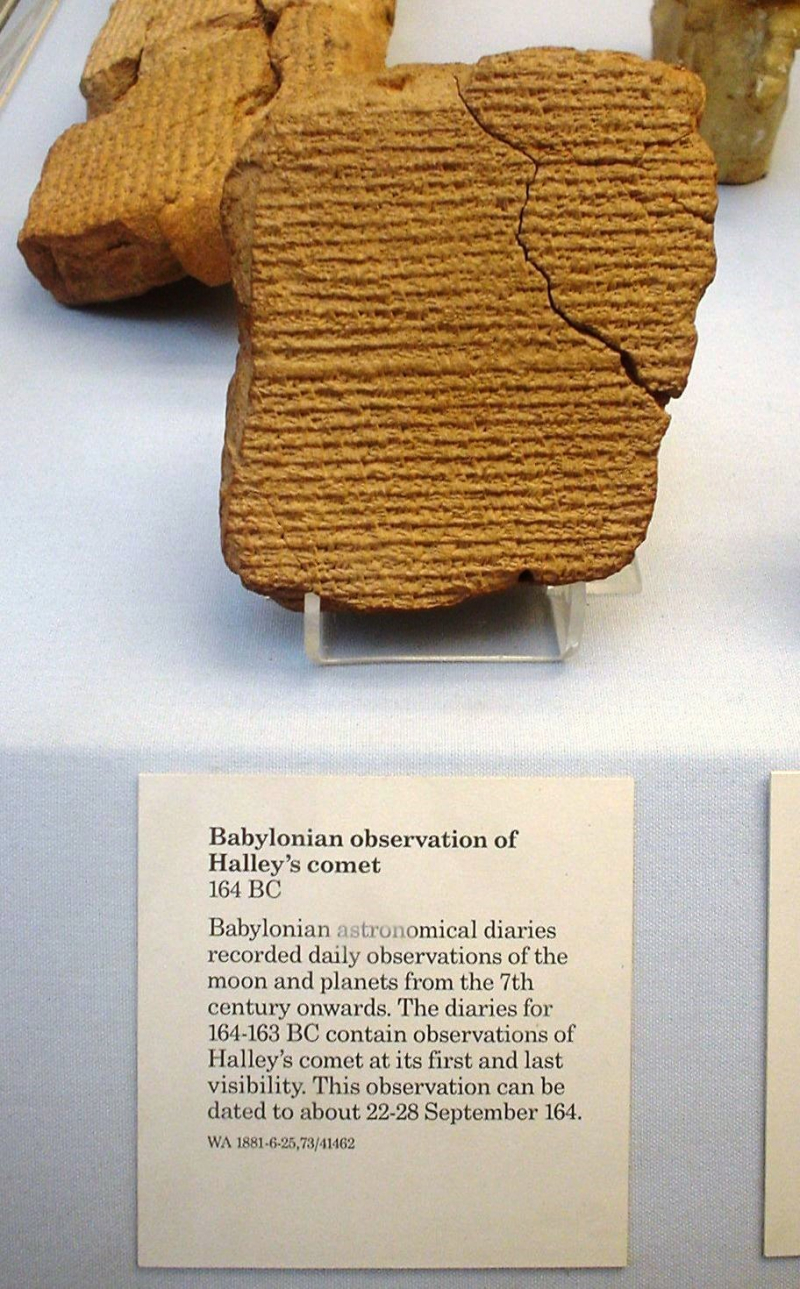

The Babylonian astronomers were mathematicians who could forecast eclipses and solstices. In astronomy, scholars believed that everything had a purpose. The majority of these are about religion and omens. Mesopotamian astronomers devised a 12-month calendar based on lunar cycles. The year was divided into two seasons: summer and winter. The origins of astronomy and astrology can be traced back to this period.

Babylonian scientists created a new method of astronomy between the eighth and seventh centuries BC. They began studying philosophy in order to understand the ideal nature of the early world, and they began using internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. This was a significant contribution to astronomy and science philosophy, and some scholars referred to this new method as the first scientific revolution. This new astronomical approach was accepted and developed further in Greek and Hellenistic astronomy.

The astronomical reports in the Seleucid and Parthian periods were thoroughly scientific; how much earlier their superior understanding and procedures were developed is unknown. The invention of systems for predicting the motions of the planets by the Babylonians is regarded as a watershed moment in the history of astronomy. Much of Greek, classical Indian, Sassanian, Byzantine, Syrian, medieval Islamic, Central Asian, and Western European astronomy was based on Babylonian astronomy.

webspace.science.uu.nl

A Babylonian tablet recording Halley's comet in 164 BC -commons.wikimedia.org -

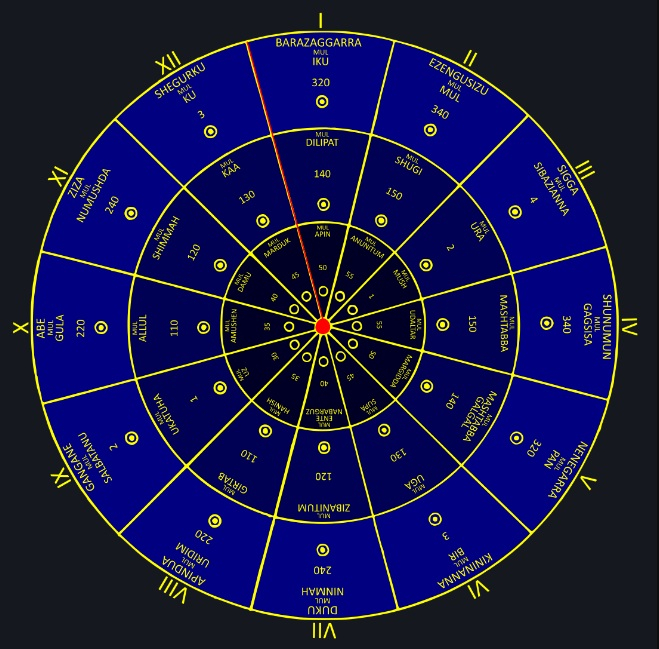

Another outstanding achievement of Mesopotamia is astrology. Astrology is a set of divinatory methods that, since the 18th century, have been acknowledged as pseudoscientific, claiming to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by observing the apparent locations of celestial objects. Since at least the second millennium BCE, several societies have used variations of astrology, which began in calendrical systems used to predict seasonal shifts and interpret celestial cycles as indications of divine communications.

Western astrology, one of the oldest currently in use, may be traced back to Mesopotamia in the 19th-17th centuries BCE, from where it spread to Ancient Greece, Rome, the Islamicate world, and eventually Central and Western Europe. In Babylon, as well as Assyria, which is a direct offshoot of Babylonian culture, astrology is one of the two chiefs' means at the disposal of the priests (who were called bare or "inspectors") for ascertaining the will and intention of the gods, the other being the inspection of the livers of sacrificial animals.

The development of astronomical knowledge within the context of divination can be seen in the history of Babylonian astrology. The oldest known detailed texts of Babylonian divination are a set of 32 tablets with inscribed liver models originating from around 1875 BC, and these reflect the same interpretational framework as that used in celestial omen analysis. Blemishes and marks observed on the sacrificial animal's liver were understood as symbolic signals conveying messages from the gods to the king. The gods were also thought to manifest as heavenly pictures of the planets or stars with which they were linked. Evil celestial omens associated with any given planet were thus interpreted as signs of unhappiness or unrest with the god that planet represented. Such signs were met with attempts to satisfy the god and find workable means for the god's expression to be realized without causing considerable harm to the king and his nation.

sevenstarsastrology.com

ancient-origins.net -

Around 4000 BC, one of the first calendars was created in Mesopotamia. Mesopotamian astronomers devised a 12-month calendar based on lunar cycles. The year was divided into two seasons: summer and winter. The Babylonian calendar is based on a Sumerian (Third Dynasty of Ur) forefather recorded in the Shulgi Umma calendar (c. 21st century BC). It was a lunisolar calendar, with years made up of 12 lunar months, each commencing when a new crescent moon was first seen low on the western horizon at nightfall, with an intercalary month inserted as needed by decree.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the solar year in Mesopotamia was divided into two seasons: "summer," which included the barley harvest in the second part of May or early June, and "winter," which roughly matched today's fall-winter. In northern regions, three seasons (Assyria) and four seasons (Anatolia) were counted, but in Mesopotamia, the division of the year looked natural. Prognoses for the well-being of Mari, on the middle Euphrates, were taken for six months as late as around 1800 BCE.

The months began with the first sighting of the New Moon, and court astronomers still reported this important observation to the Assyrian monarchs in the 8th century BCE. Month names varied from city to city, even within the same Sumerian city of Babylonia, a month could have numerous names derived from festivals, duties (e.g., sheepshearing) typically conducted in the particular month, and so on, according to local demands. On the other hand, as early as the 27th century BCE, the Sumerians utilized artificial time units to refer to the term of a high official—for example, on N-day of PN, the governor's turn of office. The Sumerian government also required a time unit that encompassed the entire agricultural cycle, such as from the delivery of new barley and the settlement of relevant accounts to the following crop.

Ancient Mesopotamia calendar -kids.britannica.com

Zuist calendar.svg - commons.wikimedia.org -

One of the inventions and achievements of Mesopotamia is cylinder seals. The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BC; sometimes known as the Protoliterate period) in Mesopotamian history lasted from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to the Early Bronze Age, following the Ubaid period and preceding the Jemdet Nasr period. This time, named after the Sumerian metropolis of Uruk, saw the rise of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization. The late Uruk period (34th to 32nd centuries) relates to the Early Bronze Age and saw the gradual formation of the cuneiform script; it has also been referred to as the "Protoliterate period."

Seals were used to secure stocked or swapped products, to secure storage places, or to identify an administration or merchant. They have been documented from the middle of the seventh millennium BC. Their use spread with the rise of institutions and long-distance trade. Cylinder seals (cylinders etched with a motif that could be rolled over the clay to stamp a symbol in it) were invented and superseded simple seals during the Uruk era. They were used to seal clay envelopes and tablets, as well as to authenticate things and goods because they served as a signature for the person who applied the seal or for the institution that they represented. These cylinder seals would be a defining feature of Near Eastern civilization for millennia. The reasons for their appeal resided in the potential of an image and hence a message with more depth, a narrative structure, and possibly an element of enchantment that they gave.

historyonthenet.com

britishmuseum.org -

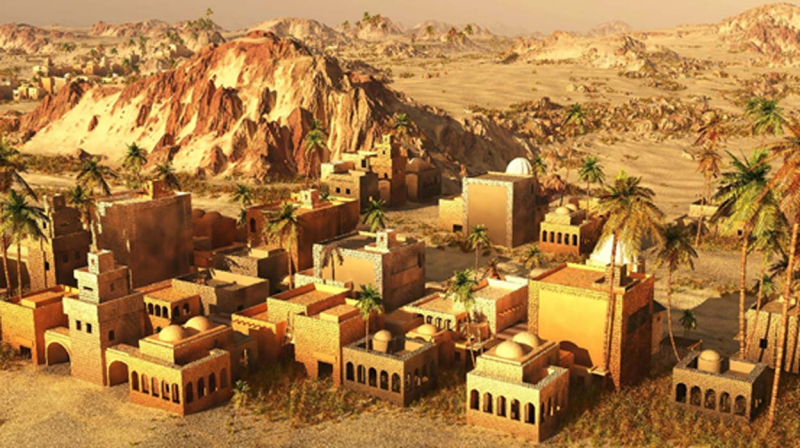

Some settlements gained significant importance and population density during the Uruk period, as well as the development of monumental municipal architecture. They have progressed to the point where they can legitimately be called cities. This was accompanied by a series of social changes that resulted in what can fairly be called an urban society as opposed to the rural society that provided food for the growing portion of the population that did not feed itself, though the relationship between the two groups and the views of the time about this distinction remain difficult to discern.

Uruk's urban site significantly outnumbered all others during the Late Uruk period. Its size, the scale of its monuments, and the significance of the administrative tools discovered there all point to it being an important center of authority. As a result, it is frequently referred to as the first city, yet it was the result of a process that began several years earlier and is widely attested outside of Lower Mesopotamia (aside from the monumental aspect of Eridu).

The formation of significant proto-urban centers began in southwest Iran (Chogha Mish, Susa) at the beginning of the 4th millennium BC, particularly in the Jazirah (Tell Brak, Hamoukar, Tell al-Hawa, Grai Resh). Excavations in the latter region tend to contradict the idea that urbanization began in Mesopotamia and spread to neighboring regions; the appearance of an urban center at Tell Brak appears to have resulted from a local process involving the progressive aggregation of previously separate village communities, and without the influence of any strong central power (unlike what seems to have been the case at Uruk). Early urbanization should thus be regarded as a phenomenon that occurred concurrently in numerous locations of the Near East throughout the fourth millennium BC, though further research and excavation are required to clarify this process.

ancient-origins.net

aa.com.tr -

One of the inventions and achievements of Mesopotamia that we want to introduce to you is reed boats. Reed boats and rafts are among the oldest known types of boats, along with dugout canoes and other rafts. They are still used in a few places throughout the world as traditional fishing boats, however, they have mostly been supplanted by planked boats. Reed boats can be distinguished from reed rafts because reed boats are typically waterproofed with tar. Small floating islands made of reeds have been built beside boats and rafts.

According to researcher Kris Hirst, Mesopotamian reed boats are the earliest known evidence of purposefully constructed sailing ships, dating to the early Neolithic Ubaid culture of Mesopotamia around 5500 B.C.E. The small, masted Mesopotamian boats are thought to have permitted minor but substantial long-distance trade between the Fertile Crescent's burgeoning villages and the Arabian Neolithic communities of the Persian Gulf. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers were followed by boatmen down into the Persian Gulf and along the shores of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Qatar. The earliest evidence of Ubaidian boat trade into the Persian Gulf was discovered in the mid-20th century when Ubaidian pottery was discovered at a number of coastal Persian Gulf locations.

Totora reed fishing boats on the beach at Huanchaco, Peru -en.wikipedia.org

pinterest.com -

A sail is a tensile structure composed of fabric or other membrane materials that harnesses wind force to propel sailing craft such as sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even land vehicles propelled by sails. Sails are typically three- or four-sided and manufactured from a combination of woven materials such as canvas or polyester cloth, laminated membranes, or bonded filaments.

Archaeological examinations of Cucuteni-Trypillian culture ceramics suggest that sailing boats were used as early as the sixth millennium BCE. Excavations in Mesopotamia from the Ubaid period (c. 6000-4300 BCE) reveal direct evidence of sailing vessels. According to Joshua J. Mark (a freelance writer and scholar), the sail evolved from seeing the effects of wind on a piece of cloth, most likely when it was hung out to dry after washing. Many merchants traded on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and had little trouble rowing or poling their boats downstream, but going back up was a different story. Rowers had to battle the current upstream in small reed-built boats that may fill and capsize as they battled the current. With the introduction of the sail, a trader could return to the point of origin much more easily and bring considerably more things on the return voyage than before. Sails were rectangular or square in shape and constructed of linen or papyrus. Long-distance maritime trade with Egypt and the Indus Valley Civilization became possible once the sail was perfected, bringing a broader range of goods to Mesopotamia than ever before.

sites.google.com

brighthubengineering.com