Top 9 Facts about David Livingstone

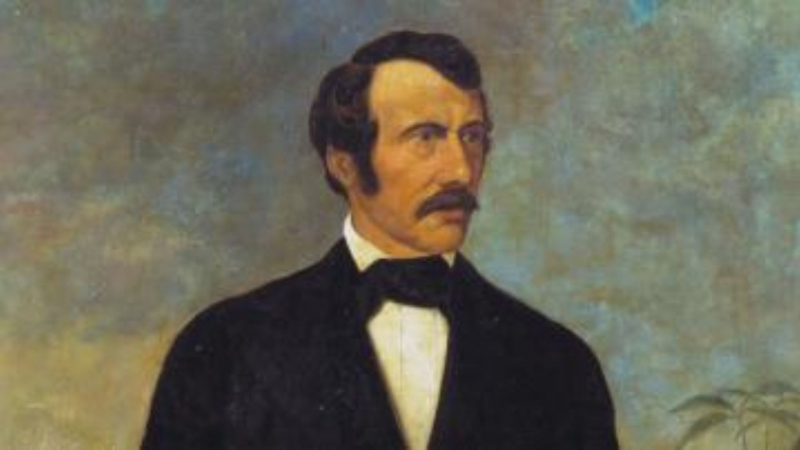

One of the most well-known British heroes of the late 19th-century Victorian era was David Livingstone, a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneering ... read more...Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society. He was also an explorer in Africa. To know more about him, let's take a look at some facts about David Livingstone!

-

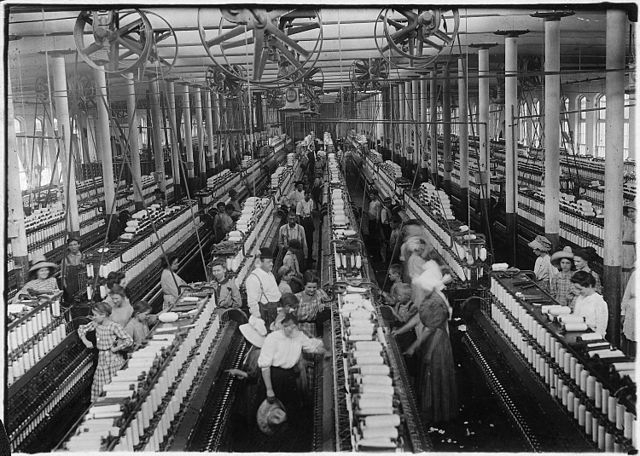

The first fact about David Livingstone is that he used to work in a cotton mill factory. In the shuttle row housing for factory workers, David was born on March 19, 1813. He resided in a single room, referred to as a single-end, with his family. The Livingstone family home once housed seven people, including David, his mother and father, two brothers, and two sisters. It was so small! David started working as a piecer at the cotton mill when he was 10 years old since his family was extremely underprivileged. In order to weave the frayed strands together, his employment required him to duck underneath the cotton spinning machines. He had to be careful not to be hurt because this was extremely risky work and the machines were constantly moving.

Life in the mill was challenging because of the demanding managers, long hours, meager pay, and noisy equipment that could induce deafness. David went to school in the evening after a long day at work (6 am to 8 pm). He left the cotton factory to pursue his dream of becoming a missionary doctor via diligence, research, and passion. These tools are made to connect the Curriculum for Excellence objectives to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Sustainable Development Goals 8 and 12, and other related goals.

Photo: AFK Travel

Photo: Visitors Guide to Scotland -

In David's life and work, religion had a significant influence. Livingstone spent a significant portion of his youth attempting to balance his passion for science with his unwavering belief in God. His father was a door-to-door tea seller who also taught Sunday school and was a teetotaller who distributed Christian literature. He consumed a lot of books on theology, travel, and missionary endeavors. His father read him Bible stories when he was a young child, and he went to the neighborhood church twice each Sunday. He discovered what Christian missionaries, people who travel the globe to share their faith with others, do. David was influenced by the writings of German missionary Karl Gützlaff, who counseled other missionaries to train as physicians in order to carry out their work and convert people by attending to their medical needs.

Nevertheless, Livingstone studied hard and saved money in order to enroll in Glasgow College in 1836 after hearing the German missionary Karl Gutzlaff's 1834 request for medical missionaries for China. David received his training at the London Missionary Society after completing his medical education in 1840. He then intended to travel to East Asia, but the first Opium War between Britain and China broke out. By chance, he attended a speech given by Scottish missionary Robert Moffat, who was visiting his station in Southern Africa. David chose to travel to Southern Africa as a result of being moved by Moffat's tales.

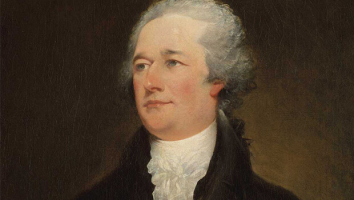

Karl Gützlaff (Photo: Wikipedia)

Photo: Heritage History -

Another fact about David Livingstone is that he did not originally go to Africa. Despite the fact that Livingstone had heeded Gützlaff's appeal for missionaries to go to China, the LMS directors were hesitant to send recruits because of the impending First Opium War. They wanted him to be engaged in the West Indies "in preference to South Africa," Cecil informed him when he asked to extend his probationary training at Ongar. He stated in a letter to the LMS directors dated July 2, 1839, that the West Indies were by that point well-served by doctors and that he had never been particularly drawn to a permanent pastorate. He continued receiving theological instruction from Cecil with LMS approval till the end of the year before starting his medical studies again.

He returned to Mrs. Sewell's missionary boarding home in Aldersgate, where he had previously lodged whilst in London, when he started his clinical study in January 1840. The missionary Robert Moffat, who was at the time in England with his family to promote the work of his LMS mission in Kuruman in South Africa, periodically paid the other guests there a visit. At the time, European explorers had not yet traveled much of the interior of Africa. Livingstone was completely engrossed in Moffat's stories. He promptly embarked on his missionary journey to Bechuanaland (modern-day Botswana), hoping to advance abolitionism in southeast Africa.

Photo: Ecyclopedia Britannica

Photo: Posterazzi -

The early years of Livingstone's career as a missionary were active. Livingstone believed that if he could kill only one lion during his visit to Mabotsa in Botswana, the other lions would consider it as a warning and leave the villages and their animals alone. The area was being terrorized by many lions. As he moved forward to begin his lion hunt, Livingstone drew the attention of a big lion and shot his gun. Unfortunately for the Scottish missionary, the animal was not severely hurt enough to stop it from attacking him as he was reloading, leaving his left arm with life-threatening injuries. Mebalwe diverted its attention by attempting to shoot the lion, saving his life. He was also bitten. Just before it died, a man who attempted to spear it was attacked.

Even though he and Edwards fixed Livingstone's shattered bone improperly, it bonded tightly. He traveled to Kuruman for healing, where he was attended to by Mary Moffat, and they later became engaged. He was able to shoot and lift heavy objects once his arm healed, but it caused him a lot of pain for the rest of his life and he was only able to lift it to his shoulder.

Photo: History

Photo: Mary Evans Prints Online -

Livingstone first encountered the father of the man who had encouraged him to travel to Africa in the early 1840s. In the Northern Cape Province of South Africa, close to the location where Livingstone had been stationed, Mary Moffat worked as a teacher in the Kuruman school. In 1845, the two made the decision to wed despite Mary's mother's opposition. David would take Mary along on several of his escapades in Africa, and she gave birth to six of his children. Having reunited with her husband at the mouth of the Zambezi River in 1862, she would later sadly pass away from malaria.

The union of Livingstone and Mary Moffat in 1845 was initially just a practical, unromantic endeavor. Livingstone had come to the conclusion that he required a wife to assist him in his missionary effort. At the age of 23, Mary desired to acquire a home of her own and anticipated joining a missionary organization like that of her parents. Both were limited in their options for marriage partners at the isolated Kuruman mission site. Livingstone didn't exactly gush over his new wife, calling her "a plain, practical woman, not a romantic.” But with time, he developed a strong love for her. This is also the fifth fact in the list of facts about David Livingstone we want to mention.

Photo: LIFE & WORK Magazine

Photo: The Herald -

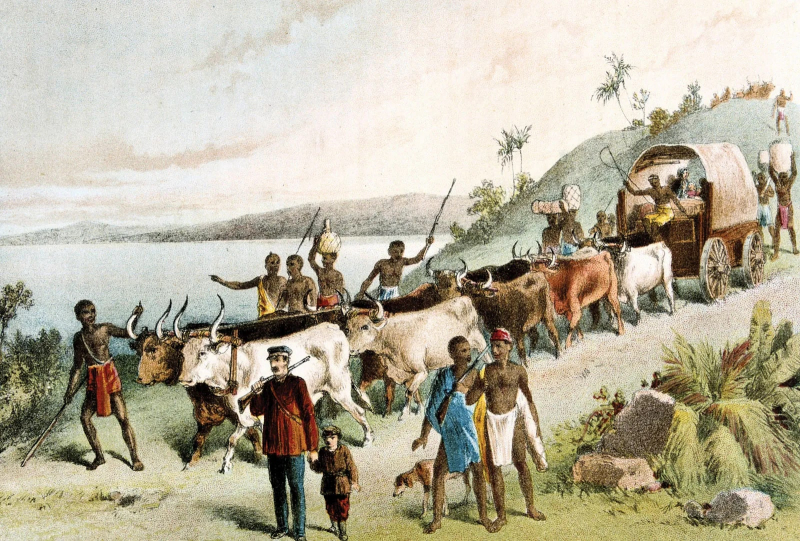

Europeans had not previously explored the interior for good reasons. The majority of explorers were unprepared to handle tropical illnesses. Tribes who perceived explorers as intruders also targeted them. Because of this, Livingstone only brought a small number of native servants, a few firearms, and basic medical supplies. In 1852, Livingstone's expedition started. He sought to teach Christianity and the abolitionist message gently rather than intimidating proud chiefs into submission because he was familiar with and respected the customs of the African tribes. The chiefs took a liking to him and even offered him soldiers to help him in his grandiose plan to survey the Zambezi river all the way to the sea - a trans-continental voyage that no European had ever made before, despite several efforts.

The missionary-explorer had left Linyanti, in what is now Namibia, in 1853 in search of a passage to the Atlantic coast that he hoped would pave the way for Western trade and Christianity to spread throughout the interior of the continent. He traveled north along the Zambezi, then north-west. He arrived at the Angolan port of Luanda, which Livingstone despised, at the end of May 1854 with his small escort of Makololo, warlike tribesmen from the Linyanti region. On November 16, 1855, Livingstone arrived at Victoria Falls after a protracted period of exploration. His subsequent works, in which he states: "Scenes so exquisite must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight," give us an idea of his awe at the sight.

Photo: Overseas Adventure Travel

Photo: James Arsenault -

Although there was already a well-established trans-regional network of trade routes, Livingstone rose to fame as the first European to cross south-central Africa at that latitude and was credited with having "opened up" Africa. Portuguese traders had traversed the continent from both sides to the middle; in 1853–1854, two Arab traders traveled from Zanzibar to Benguela; and in the early 1800s, two native traders traveled from Angola to Mozambique. However, Livingstone's main objective was to end the African slave trade, which was practiced by the Portuguese of Tete and the Arab Swahili of Kilwa.

When Livingstone made three lengthy voyages across Africa, he aimed to spread Christianity, commerce, and "civilization" there. His statue, which is located near to Victoria Falls, is inscribed with this saying, which he upheld throughout his whole missionary career. He hoped that this combination would create an alternative to the slave trade and give Africans respect in the eyes of Europeans. He thought that using the Zambezi River as a Christian trade route into the interior was the key to achieving his objectives. The phrase was adopted as a slogan by British Empire administrators to support the growth of their colonial domain. It came to represent neo-Darwinist notions of the "White Man's Burden," which held that it was the duty of European nations to spread civilization throughout the rest of the globe. Because of this, colonial aspirations were seen as an "obligation" for European powers. That's all about the seventh fact about David Livingstone.

Photo: British Heritage Travel

Photo: The Times -

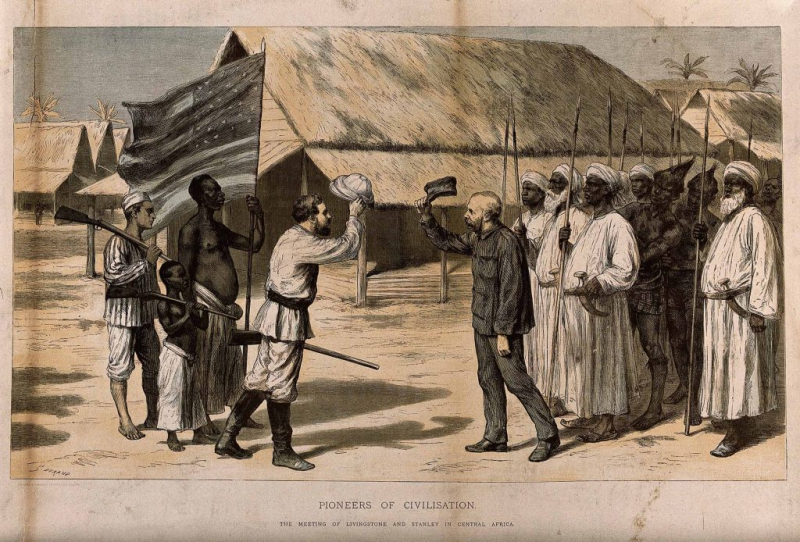

The New York Herald newspaper had dispatched Henry Morton Stanley to locate him in 1869. On November 10, 1871, he came across Livingstone in the village of Ujiji on the beaches of Lake Tanganyika, and he reportedly greeted him with the now-famous phrase "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" Yes, said Livingstone, adding, "I feel grateful that I am here to welcome you." Stanley later tore the pages of this incident from his diary, raising the possibility that these infamous comments were a fabrication. These words are not mentioned at all in Livingstone's description of the encounter. The statement does, however, appear in a New York Herald editorial from August 10, 1872, and it is quoted without hesitation in both the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Stanley's awkward attempt to sound dignified in the African wilderness by delivering a formal greeting one might expect to hear in the confines of an upper-class London club, together with Livingstone being the only other white person for hundreds of miles, are what make the words memorable. But the Herald's readers quickly recognized Stanley's pretense. Tim Jeal, Stanley's biographer, remarked that Stanley battled his self-perceived weakness of coming from a lowly background throughout his life and created events to make up for this alleged shortcoming. According to Stanley's autobiography, the reason for this welcome was actually embarrassment because he dared not embrace Livingstone.

Photo: Brewminate

Photo: The Kemscott Bookshop -

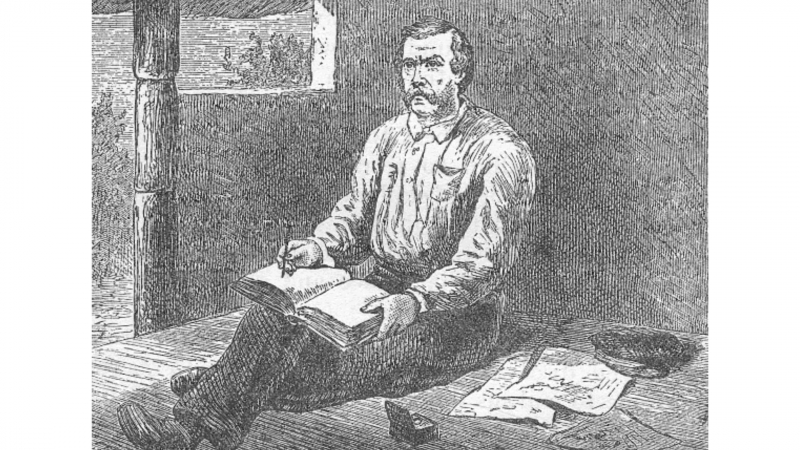

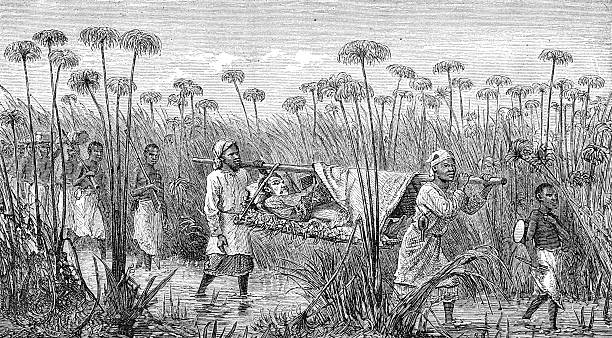

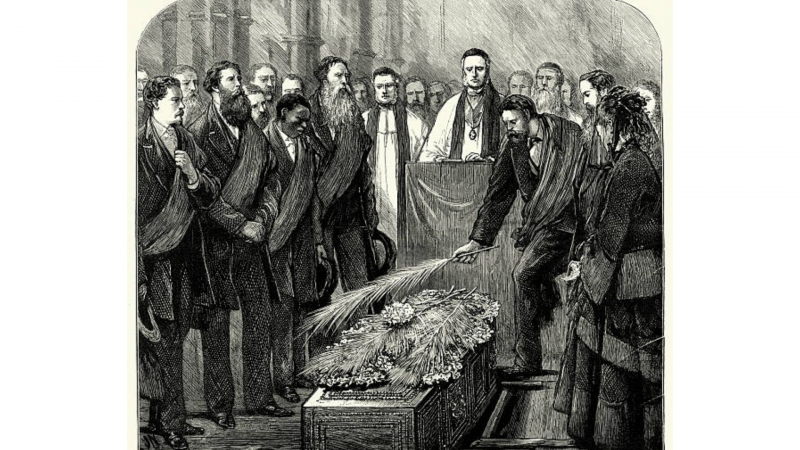

The next fact about David Livingstone is that he died in the African Wilderness. Livingstone, 60, passed away from internal bleeding brought on by dysentery and malaria on May 1, 1873, in Chief Chitambo's hamlet at Chipundu, in what is now Zambia. Chuma and Susi, two of his devoted servants, led his expedition in planning burial rites. The tree, which has been alternately identified as a mvula tree or a baobab tree but is more likely to be an mpundu tree given that baobabs are found at lower elevations and in more dry locations, was where they extracted his heart and buried it. He did more than any other individual to end slavery in that region of the world, which he had studied so thoroughly, and he left a legacy of mutual respect among the native people he encountered.

The Livingstone Memorial website lists Livingstone's passing as occurring on May 4, which is the date given by Chuma and Susi. However, most sources agree that Livingstone actually passed away on May 1, the date of his last journal entry. The remainder of his remains, along with his final journal and belongings, were then transported by the expedition headed by Chuma and Susi over a distance of more than 1,600 kilometers in 63 days to the coastal town of Bagamoyo. The journey was finished by 79 followers, the men received their just wages, and Livingstone's bones were sent back to Britain by ship for burial. Before being buried at Westminster Abbey, his body was laid to rest in London at No. 1 Savile Row, which was then the Royal Geographical Society's headquarters.

Photo: iStock

Photo: iStock