Top 10 Founding Mothers of the United States

Unfortunately, many of the women who are cited as heroes throughout the American Revolutionary period come more from folklore than from historical accounts. ... read more...One of these women was probably a composite of several others who accompanied the Continental Army into battle. She was named Molly Pitcher. Others include Sybil Ludington and Betsy Ross, whose accounts didn't surface until decades after the Revolution and aren't backed up by any contemporary records. Here are 10 women whose contributions to the Constitution, the Revolutionary War, and the Declaration of Independence need more recognition.

-

One of history's most prolific letter writers was Abigail Adams. She wrote to practically all of the Founders during her lengthy life, in addition to her husband during his numerous extended absences. She sent letters to numerous people, including Jefferson, Washington, Lafayette, John Dickinson, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Benjamin Rush, and Benjamin Franklin, who replied in the stiff style of the time. And the majority of her letters, which have survived, show how strongly she pushed the founders to embrace women's rights, democracy, and independence.

During the French Revolution, she traveled to Paris with her husband, and her letters reflect her New England Puritan disdain for many of the court's customs. She went with him to the Court of St. James where she was introduced to the King and made equally scathing remarks about British culture. She reprimanded her husband during the Constitutional Convention to make sure that women's rights were taken into account and given equal respect. She wrote to Jefferson following their political disagreement to defend her husband's views and deeds.

In 1800, when she and her husband first moved into the White House, they discovered it to be unfurnished, lacking in landscaping, and insufficiently heated. As the story goes, she did hang her washing in the unfinished East Room. Years earlier, through her husband John, she wrote the all-male Continental Congress a letter warning them that "if particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation."Despite John's resistance to Abigail's criticisms, which he referred to as a "despotism of the petticoat," Abigail had a remarkable amount of influence over the founders. She "would have been a greater President than her husband," Harry Truman famously said of her.

- Born: Abigail Smith, November 11, 1744Weymouth, Massachusetts Bay, British America

- Died: October 28, 1818 (aged 73)Quincy, Massachusetts, U.S.

- First Lady of the United States ( March 4, 1797 – March 4, 18010

- Second Lady of the United States ( April 21, 1789 – March 4, 1797)

http://allencbrowne.blogspot.com

https://www.thoughtco.com - Born: Abigail Smith, November 11, 1744Weymouth, Massachusetts Bay, British America

-

Martha was a well-off widow when she wed George Washington, and she gave her new husband a sizable dowry, property, and two kids from her previous union with Daniel Parke Custis. 14 years after their 1759 wedding, her daughter Martha, also known as Patsy, passed away due to a seizure. Despite having a seemingly blissful marriage, the Washingtons never had children.

Martha traveled with Washington when he first traveled to New York and then Philadelphia to assume the role of President of the United States after coming out of retirement. At the time, the gatherings were known as weekly Presidential levees, and she served as the hostess. Without any rules to guide her, and with no official responsibilities given to her, she took on the position of First Lady. Few of her letters to Washington have survived; after his death in 1799, she burnt the majority of their private correspondence.

Some erstwhile revolutionaries also expressed concern that the levees she hosted resembled the European Royal Courts in an uncanny way. But she overcame and, after once more serving in her famous husband's shadow, departed Philadelphia for Mount Vernon in 1797 as a respected and admired woman and hostess. Indeed, throughout her tenure as the nation's first lady, her reputation improved, but her husband's had seen a sharp reversal.

- Born: Martha Dandridge, Martha Dandridge, June 2, 1731, Chestnut Grove, Virginia, British America

- Died: May 22, 1802 (aged 70), Mount Vernon, Virginia, U.S.

- First Lady of the United States (April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797)

https://uspresidentialhistory.com

https://npg.si.edu/ -

Sarah Livingston Jay was the wife of one Constitutional signer and the daughter of another (William Livingston) (John Jay). Sarah was brought up in the upper echelons of colonial American society as the daughter of a powerful and affluent New York family. She followed her husband, John Jay, when he was despatched by the Continental Congress to France to join the group led by Benjamin Franklin after serving as minister in Spain. In order to improve diplomatic relations, she copied Franklin's strategy of involving Americans in the higher echelons of French society.

Adrienne, the Marquis de Lafayette's wife, Abigail Adams, and other American spouses living in Paris were all involved in Sarah's social circle. She rose to prominence in French society, and on at least one occasion, the audience applauded as she entered her box during a play, stopping the performance. Later, she presided as New York's First Lady while her husband was governor and as the Supreme Court's socialite when he was the country's Chief Justice.

Sarah worked as a hostess and socialite in Washington. She was a notable member of George Washington's cabinet who spoke French fluently and was renowned for her subtlety and diplomacy. Her life was inextricably entwined with her husband's, a 19th-century tradition known as coverture, like that of the majority of the Founding Mothers. However, she made a vital contribution to the events that led to the Jay Treaty with Great Britain, the Treaty of Alliance with France, and the important choices taken in the early years of the new American government.- Born; Sarah Van Brugh Livingston, August 2, 1756, British America

- Died: May 28, 1802 (aged 45)Bedford, New York

- First Lady of New York (July 1, 1795 – June 30, 1801)

https://www.walmart.com/

https://www.flickr.com/ -

Elizabeth Schuyler, sometimes known as Eliza to her friends, is a rich New Yorker who is descended from the Van Rensselaers and the Schuylers. She first met her husband, Alexander Hamilton, in 1780 at the Continental Army encampments at Morristown, New Jersey, when he was a member of George Washington's staff. In the Schuyler house in Albany, they were wed in December of that same year. Eliza, who was his wife, had a significant impact on the Constitution's drafting and the formation of the US federal government.

Eliza assisted Alexander Hamilton in writing his contributions to the collection of essays now known as the Federalist Papers during the discussions over the Constitution's ratification. Eliza suffered a miscarriage and learned that her husband was having an affair during the two terms of President George Washington, which temporarily tore them apart but ultimately brought them back together. For nearly two decades, researchers were unaware that Hamilton and Eliza collaborated on a large portion of the essay Washington wrote for his Farewell Address.

Eliza contributed to the establishment of the Orphan Asylum Society in New York after both her son and her husband were killed in duel. She volunteered with the organization for more than 40 years, helping to raise funds, gather supplies, and oversee the upbringing and care of over 700 orphaned or abandoned children. The society is still active today under the name Graham Windham. She also fought to preserve her husband's works, personal documents, and legacy, leaving much of what is known about the complex person that was Alexander Hamilton to future generations. She outlived her husband by 50 years and passed away in 1854. In the Trinity Church cemetery in New York, she was interred close to Alexander.- Born: Elizabeth Schuyler, August 9, 1757Albany, Province of New York, Thirteen Colonies

- Died: November 9, 1854 (aged 97) Washington, D.C., U.S

http://twonerdyhistorygirls.blogspot.com/

https://www.thefamouspeople.com -

During Thomas Jefferson's presidency, Dolley Madison got her start as a White House hostess. When his daughter was unable to do that duty on multiple occasions, the widowed President requested her to step into that position. Dolley is credited for making the Executive Mansion and the President's table the social hubs of early Washington, positions they still hold today, more than 200 years later. However, it's safe to say that it wasn't her only contribution to American history at that time.

Dolley collaborated with architect Benjamin Latrobe to help equip the White House. She also contributed to the social organization of occasions like State Dinners and other formal gatherings. She was the only First Lady in American history to be given an honorary seat in the House of Representatives thanks to her use of social gatherings to spark political conversations and reach agreements. Despite popular belief, Elizabeth did not save the famous Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington from the White House fire in 1814, but she did order its removal and transportation to safety.

Dolley Madison formalized the First Lady's position considerably more than her predecessors did. She strongly backed her husband's goals and positions as President and head of his political party by utilizing the position. Dolley moved back to Washington after Madison's passing and the forced sale of his Montpelier property to settle his debts, where she remained for the majority of the rest of her life while still a prominent member of Washington society. At the age of 81, she passed away in 1849. She was first buried in Washington, but it was later unearthed and reburied next to her husband, James Madison, at Montpelier.- Born: Dolley Payne , May 20, 1768Guilford County, North Carolina, British America

- Died: July 12, 1849 (aged 81)Washington, D.C., U.S.

- First Lady of the United States ( March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817)

https://history-first.com/

http://greensborohistory.org/ - Born: Dolley Payne , May 20, 1768Guilford County, North Carolina, British America

-

Even though the Pennsylvania delegation, of which John Dickinson was a member, voted in favor of independence in 1776, he declined to sign the Declaration of Independence. He rejected in part because he was a Quaker and felt the document would result in protracted conflict, which would go against his moral beliefs. Mary Norris Dickinson, his wife, had the same religious beliefs. Men and women are treated equally by the Society of Friends, who also believe that spirits are genderless. Mary Norris Dickinson used this maxim to all aspects of her life, including business and politics.

When her husband was a delegate from Delaware to the Constitutional Convention, Mary was the owner of sizable tracts of land and one of the greatest private libraries in North America. To the chagrin of some of the more conservative-minded delegates, Mary routinely hosted delegates for dinners in her home during the convention, where she actively participated in political discussions. She didn't follow the custom of the ladies leaving the table after dinner to let the men talk about things like politics and business; instead, she invited other women to join her conversations.

She exerted influence on her husband and other delegates to push for the inclusion of a bill of rights and the equal treatment of men and women in all legal proceedings. She also promoted women's voting rights. Despite parts of her estates being destroyed by the British during the Revolution, her library was not. She and her husband gave Benjamin Rush the land close to Carlisle and the library in 1784, so he could establish a new college, which he named John and Mary's College. Its current name is Dickinson College.

- Born: July 17, 1740 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – July 23, 1803 in Wilmington, Delaware

- Died: Wilmington, Delaware, on July 23, 1803

https://www.wikiart.org/ -

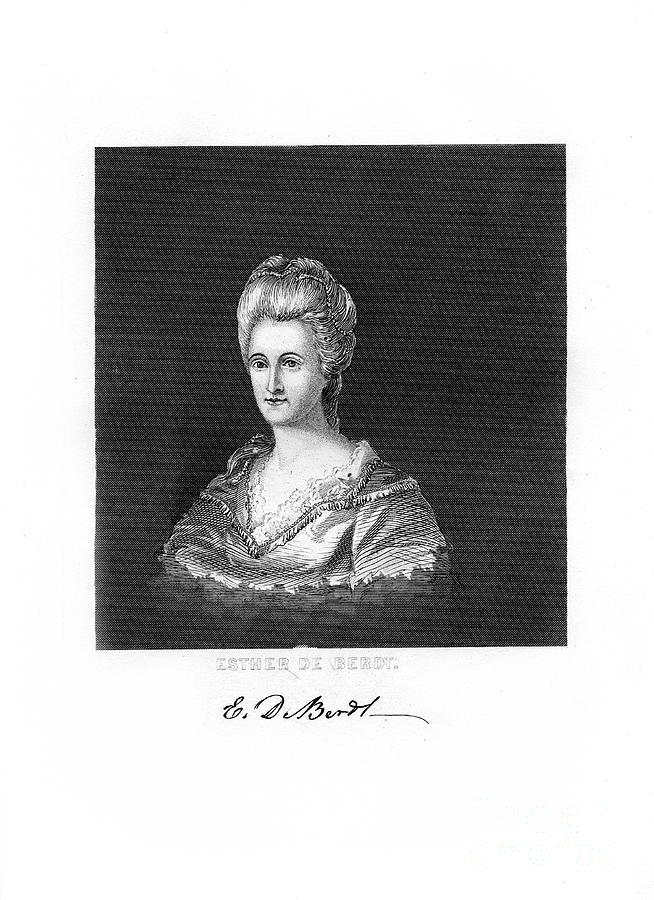

The Ladies Association of Philadelphia was established, according to a brochure that first appeared in Philadelphia in January 1780. Its author could only be identified by its title, Sentiments of an American Woman. Like many other Americans since, that American woman was a foreign-born citizen. She was Esther de Berdt Reed, a native of England who married Joseph Reed, a well-known Philadelphia lawyer who was at the time George Washington's assistant in the Continental Army. Joseph Reed was a distinguished Philadelphia attorney.

The Ladies Association declared its purpose to raise funds for the Continental troops' upkeep, who up until that point were frequently unpaid. The necessary monies couldn't be raised by Congress. The Ladies Association had greater success, but Washington was reluctant to provide the money to the troops directly out of concern that they might spend it on alcohol. The money was spent, at the General's request, on food and clothing for his men. Direct correspondence between Washington and de Berdt resulted in a productive working relationship that she later used to help create several additional Ladies Associations in the former colonies.

For Washington's men, the Ladies Associations made shirts out of material they had purchased, sewing their initials into the seams at Esther's insistence. In the end, the 39 members of the Philadelphia Ladies Association alone produced more than 2,000 shirts. Esther did not live to see the project completed and the United States triumph. Later that year, in Philadelphia, she passed away from dysentery.- Born: October 22, 1746

- Died: September 18, 1780

https://fineartamerica.com -

Both Mercy Otis and her husband James Warren were able to trace their maternal ancestry back to the Mayflower. Both came from wealthy households in Massachusetts, and Mercy had a good education from Reverend Jonathan Russell despite never attending a formal school. Mercy was given permission by the Reverend to attend tutoring sessions while he prepared her two brothers for admission to Harvard College with the help of Mercy's father.

She applied what she had learned to produce satirical plays, pamphlets, and poetry that were published anonymously, as was the custom of the day. Throughout the protests against the Stamp Act, the Intolerable Acts, and the deployment of British troops in Boston, she supported the increasing Patriotic cause in each one of them. She routinely hosted Patriot gatherings in Boston before and throughout the war, writing to all of the Revolutionary leaders and expressing her opinions in open detail.

She kept in touch with a few of the Founders after the war, especially during the Constitutional Convention. She wrote a brochure criticizing the ratification of the Constitution without the immediate adoption of a bill of rights after it was put up for vote. She published one of the first histories of the American Revolution in the early 19th century. Nearly all of her works, including letters to George Washington while he served as America's first President, are still accessible today. Few ladies throughout the American Revolution left a more enduring legacy.- Born: Mercy Otis, September 28, 1728Barnstable, Massachusetts Bay, British America

- Died: October 19, 1814 (aged 86), Massachusetts, U.S.

https://en.wikipedia.org/

http://educators.mfa.org -

Before the American Revolution, British officers were stationed in Boston, and young bookseller Henry Knox catered to their needs. He provided the impression of being loyal to the King by allowing the British to mingle in his shop, which also offered him the opportunity to learn about British rumors and the army's tactical procedures, notably those relating to artillery. It also gave him the chance to pursue Boston's pretty Lucy Flucker, a young woman. Her parents, affluent landowners in Maine and Massachusetts, were against the union. The Knoxes were married in 1774 against the desires of her parents. When it was discovered that Henry was a patriot in 1775, Lucy's family abandoned her.

Henry Knox served as the Chief of Artillery for the Continental Army during the conflict. As part of her service, Lucy coordinated supply trains and other forms of assistance for the soldiers in the field. During the war, Lucy wrote Henry a letter in which she forewarned him that she had changed as a result of having to manage her husband's business dealings, and that upon his return, "...I trust you will not view yourself as commander in chief of your own house." Throughout the war, she joined her husband in camp at Valley Forge and other winter encampments.

Lucy supported her husband during the Revolutionary War and then in New York and Philadelphia when Henry worked as the country's first Secretary of War. Throughout their lengthy and seemingly content marriage, Lucy gave birth to 13 children, 10 of whom died as infants. She lived the rest of her days apart from her Loyalist family after 1775. Her letters to her husband, the most of which have survived, provide insightful accounts of the struggles and sacrifices made on the home front throughout the American Revolution. Throughout the founding of the United States, Lucy gave up her family, her fortune, and a life of luxury to assist the Patriot cause.- Born: Lucy Flucker, August 2, 1756Boston, Massachusetts, British America

- Died: June 20, 1824 (aged 67)Thomaston, Maine, U.S.

http://knoxmuseum.org/ -

She was born in 1738 not far from New London, Connecticut, and traveled with her brother William when he founded the Providence Gazette, a newspaper, in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1762. His newspaper soon endorsed the Patriots' operations. William also started a newspaper in Baltimore called the Maryland Journal, and in 1774 Mary took over publishing of the Maryland Journal when he went to Philadelphia to start yet another newspaper. She subsequently became among the first female publishers in history.

In addition to continuing to publish the Journal, she also assumed the responsibilities of Baltimore's Postmaster in 1775. She is regarded by some as the country's first female federal employee. When the Continental Congress in Philadelphia agreed to print the Declaration of Independence, Goddard offered her press to produce the version that is now known as the Goddard Broadside. Goddard's newspaper had supported the Patriots in the early stages of the conflict. It was the first to incorporate the signatories' names in typeset, and Goddard added her own name to the paper in a lower corner. She could have been accused of treason as a result.

In 1784, Elizabeth was made to resign from her post as publisher of the Maryland Journal by Goddard's brother William. She remained Baltimore's postmaster until Postmaster General Samuel Osgood thought the position was too demanding for a woman in 1789. Her reinstatement was not granted despite a petition from more than 200 Baltimore residents. She stayed in Baltimore and ran a bookshop there until she passed away in 1816.- Born: June 16, 1738Connecticut

- Died: August 12, 1816 (aged 78)

https://www.openculture.com/