Top 9 Interesting Facts about Ancient Mesopotamia Goddess Inanna

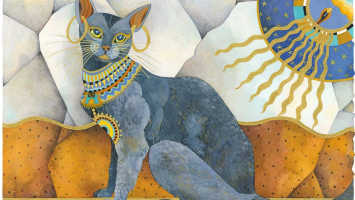

Inanna is a Mesopotamian goddess of fertility, war, and love. Her other associations include beauty, sex, justice, and political power. She was first worshiped ... read more...in Sumer as "Inanna," and afterward by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians as "Ishtar." Here are the 9 interesting facts about Ancient Mesopotamia Goddess Inanna.

-

One of the most interesting facts about Ancient Mesopotamia Goddess Inanna is that she was known as the "Queen of Heaven". The title "Queen of Heaven" was given to a variety of ancient sky goddesses who were worshiped throughout the ancient Mediterranean and the ancient Near East. Inanna, Anat, Isis, Nut, Astarte, and possibly Asherah are among the goddesses who have been referred to by the title (by the prophet Jeremiah). Hera and Juno held this title in the Greek and Roman periods. Worship forms and content varied.

The Sumerian goddess of love and war, Inanna. Despite her association with human and animal fertility, Inanna was not a mother goddess and is rarely associated with childbirth. Inanna was also linked to rain and storms, as well as the planet Venus. The Ammisaduqa Venus tablet, said to have been created about the mid-seventeenth century BCE, referred to the planet Venus as the "bright queen of the sky" or "bright Queen of Heaven."

Although the title of Queen of Heaven was frequently bestowed upon several different goddesses throughout antiquity, Inanna is the one to whom the title is bestowed the most frequently. In truth, Inanna's name is derived from Nin-anna, which literally means "Queen of Heaven" in ancient Sumerian, despite the fact that the cuneiform symbol for her name is not historically a ligature of the two. Inanna is described as the daughter of Nanna, the ancient Sumerian god of the Moon, in various stories. In other texts, however, she is frequently identified as the daughter of Enki or An. Due to these difficulties, some early Assyriologists hypothesized that Inanna was originally a Proto-Euphratean goddess, possibly related to the Hurrian mother goddess Hannahannah, who was only later accepted into the Sumerian pantheon, an idea supported by her youth, and that, unlike the other Sumerian divinities, she had no sphere of responsibility at first. Modern Assyriologists are divided on whether a Proto-Euphratean substrate language existed in Southern Iraq before Sumerian. Inanna was revered as "Queen of Heaven" in Sumer during the third millennium BC.

en.wikipedia.org

Inanna receiving offerings on the Uruk Vase -en.wikipedia.org -

The eight-pointed star was Inanna's most common symbol, however, the exact number of points varies. Six-pointed stars are fairly common, but their symbolic value is unknown. The eight-pointed star appears to have been associated with the heavens at first, but by the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 - c. 1531 BCE), it had come to be explicitly associated with the planet Venus, with which Ishtar was identified. Beginning around the same time, the star of Ishtar was usually surrounded by a circular disc. Slaves who toiled in Ishtar's temples were occasionally branded with the eight-pointed star seal in later Babylonian times. The eight-pointed star is sometimes shown on boundary stones and cylinder seals beside the crescent moon, which was a symbol of Sin (Sumerian Nanna), and the rayed solar disk, which was a symbol of Shamash (Sumerian Utu).

The doorpost of the storehouse, a traditional sign of fertility and plenty, was represented by Inanna's cuneiform ideogram, a hook-shaped twisted knot of reeds. The rosette was another prominent emblem of Inanna, and it was utilized as a symbol of Ishtar following their union. The rosette may have supplanted the eight-pointed star as Ishtar's major symbol during the Neo-Assyrian Period (911-609 BCE). The Ishtar temple in the city of Aur was embellished with many rosettes.

commons.wikimedia.org

stringfixer.com -

Inanna was associated with the planet Venus, which was called for her Roman counterpart Venus. Several hymns honor Inanna for her role as the goddess or embodiment of Venus. According to theology professor Jeffrey Cooley, Inanna's migrations in various stories may match with the movements of the planet Venus in the sky. Unlike any other deity, Inanna is able to descend into the netherworld and return to the heavens in Inanna's Descent to the Underworld. Venus appears to follow a similar pattern, setting in the west and rising in the east. An introductory song recounts Inanna departing the sky and heading for Kur, which could be interpreted as the mountains, thus recreating Inanna's rise and setting to the west.

Because Venus's movements appear to be discontinuous (it disappears for many days at a time due to its proximity to the sun, and then reappears on the opposite horizon), some cultures did not recognize Venus as a single entity; instead, they assumed it to be two separate stars on each horizon: the morning and evening star. Nonetheless, a cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period shows that the ancient Sumerians recognized the morning and evening stars as the same celestial entity. Venus's erratic movements are related to both mythology and Inanna's dual nature.

The myth of Inanna's fall into the underworld is recognized by modern astrologers as a reference to an astronomical occurrence linked with retrograde Venus. Venus departs from the evening sky seven days before its inferior conjunction with the sun. The astronomical phenomena on which the story of descent is based is the seven-day time between this disappearance and the conjunction itself. Seven days pass after the conjunction before Venus shines as the morning star, corresponding to the rising from the underworld.

eragem.com

mesopotamiangods.com -

Inanna was associated with the planet Venus, which was called for her Roman counterpart Venus. Several hymns honor Inanna for her role as the goddess or embodiment of Venus. According to theology professor Jeffrey Cooley, Inanna's migrations in various stories may match with the movements of the planet Venus in the sky. Unlike any other deity, Inanna is able to descend into the netherworld and return to the heavens in Inanna's Descent to the Underworld. Venus appears to follow a similar pattern, setting in the west and rising in the east. An introductory song recounts Inanna departing the sky and heading for Kur, which could be interpreted as the mountains, thus recreating Inanna's rise and setting to the west.

Because Venus's movements appear to be discontinuous (it disappears for many days at a time due to its proximity to the sun, and then reappears on the opposite horizon), some cultures did not recognize Venus as a single entity; instead, they assumed it to be two separate stars on each horizon: the morning and evening star. Nonetheless, a cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period shows that the ancient Sumerians recognized the morning and evening stars as the same celestial entity. Venus's erratic movements are related to both mythology and Inanna's dual nature.

The myth of Inanna's fall into the underworld is recognized by modern astrologers as a reference to an astronomical occurrence linked with retrograde Venus. Venus departs from the evening sky seven days before its inferior conjunction with the sun. The astronomical phenomena on which the story of descent is based is the seven-day time between this disappearance and the conjunction itself. Seven days pass after the conjunction before Venus shines as the morning star, corresponding to the rising from the underworld.

historyonthenet.com

commons.wikimedia.org -

It is a myth that Inanna's loyalty to her husband (Dumuzid) is questionable. Dumuzid (later known as Tammuz), the god of shepherds, is usually described as Inanna's husband, but according to some interpretations, Inanna's loyalty to him is questionable. Inanna treats her lover Dumuzid capriciously in Inanna's Descent to the Underworld. This facet of Inanna's character is emphasized in the later standard Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh when Gilgamesh mentions Ishtar's terrible mistreatment of her lovers. However, as assyriologist Dina Katz points out, the depiction of Inanna's relationship with Dumuzi in the Descent myth is uncommon. Dumuzid is commonly represented as Inanna's husband, although other interpretations doubt her commitment to him; in the narrative of her journey into the Underworld, she abandons Dumuzid and allows the Galla demons to pull him down as her replacement.

The Return of Dumuzid is a distinct myth. Instead, Inanna laments Dumuzid's death and eventually rules that he may return to Heaven to dwell with her for one-half of the year. Dina Katz observes that the portrayal of their relationship in Inanna's Descent is unusual; it differs from the representation of their relationship in other tales about Dumuzi's death, which nearly always blame it on demons or even human bandits. Researchers have compiled a substantial corpus of love poems describing encounters between Inanna and Dumuzi. Local expressions of Inanna/Ishtar, on the other hand, were not always related to Dumuzi.

Ancient Sumerian depiction of the marriage of Inanna and Dumuzid -en.wikipedia.org

Dumuzid -timelessmyths.com -

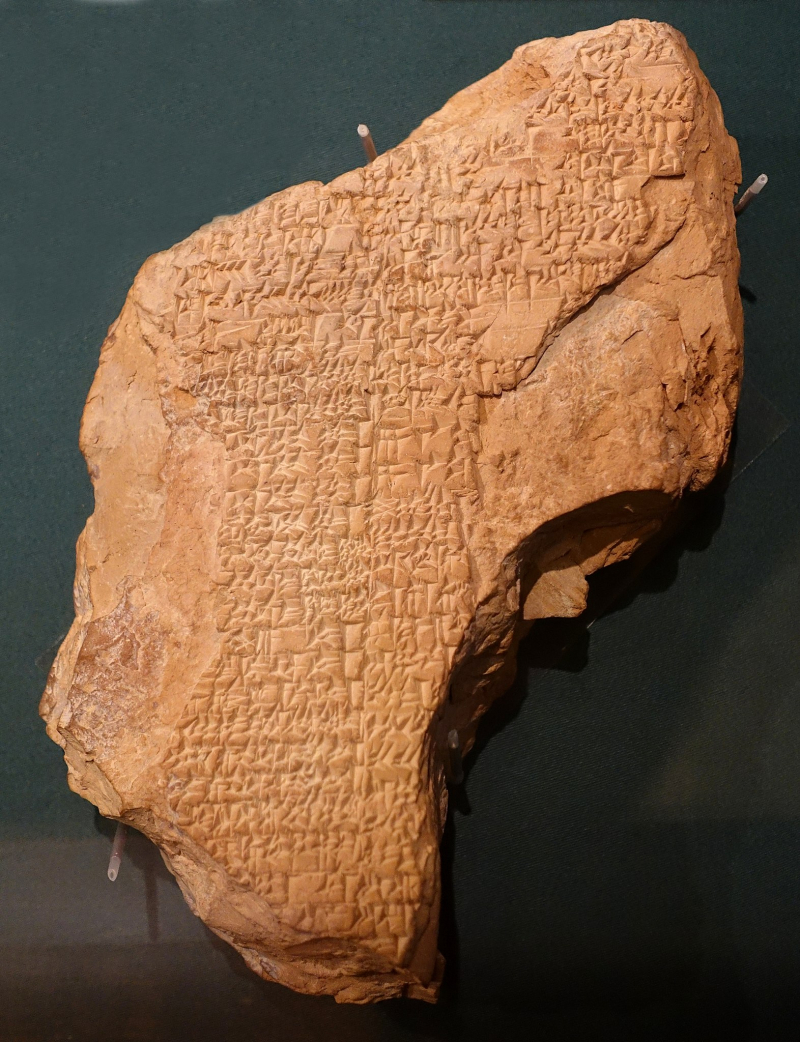

It is a fact that Inanna was regarded as the dispenser of divine justice. Inanna and her brother Utu were regarded as the dispensers of divine justice, a function that Inanna exhibits in several of her stories. Inanna and Ebih (ETCSL 1.3.2), also known as Goddess of the Fearsome Divine Powers, is a 184-line poem composed by the Akkadian poet Enheduanna that depicts Inanna's encounter with Mount Ebih, a mountain in the Zagros mountain range. The poem begins with a song that praises Inanna. The goddess travels around the universe until she comes across Mount Ebih and is enraged by its glorious majesty and natural beauty, viewing its very existence as an outright challenge to her own rule.

Inanna requests permission from An, the Sumerian god of the heavens, to destroy Mount Ebih. Anu, whose name simply means "sky" in Sumerian, was a divine representation of the sky. Anu was the celestial personification of the sky, the monarch of the gods, and the ancestor of numerous deities in Mesopotamian religion. He was revered as a wellspring of both divine and human monarchy, and his name appears at the start of numerous Mesopotamian deity enumerations. An warns Inanna not to attack the mountain, but she disregards his advice and attacks and destroys Mount Ebih anyhow. At the end of the narrative, she tells Mount Ebih why she fought it. The phrase "destroyer of Kur" is occasionally employed as one of Inanna's epithets in Sumerian poetry.

Symbols of various deities, including Anu (bottom right corner) on a kudurru of Ritti-Marduk, from Sippar, Iraq -en.wikipedia.org

Tablet describing goddess Inanna's battle with the mountain Ebih, Sumerian - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago -vi.m.wikipedia.org -

One of the most interesting facts about Ancient Mesopotamia Goddess Inanna is that she became one of the most widely venerated deities in many of the cities of Ancient Mesopotamia.Inanna amalgamated with the Akkadian goddess Ishtar, who was linked with the city of Agade, during the Old Akkadian period. A hymn from the time refers to the Akkadian Ishtar as "Inanna of Ulma," along with Inanna of Uruk and Zabalam. Sargon and his successors supported Ishtar's worship and syncretism between her and Inanna, and as a result, she swiftly became one of the most widely adored deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon. Ishtar is the most commonly invoked divinity in the inscriptions of Sargon, Naram-Sin, and Shar-Kali-Sharri.

Her principal cult centers in the Old Babylonian period included, in addition to the aforementioned Uruk, Zabalam, and Agade, Ilip. Her worship was also introduced to Kish from Uruk. While her cult in Uruk flourished later, Ishtar became primarily worshipped in the Upper Mesopotamian kingdom of Assyria (now northern Iraq, northeast Syria, and southeast Turkey), particularly in the towns of Nineveh, Aur, and Arbela (modern Erbil). Ishtar rose to become the most significant and universally worshipped divinity in the Assyrian pantheon under the reign of Assurbanipal, surpassing even the Assyrian national god Ashur. Votive items discovered in her principal Assyrian temple suggest that she was a popular female divinity.

Façade of the Inanna Temple -artsandculture.google.com

commons.wikimedia.org -

Inanna was raped by a gardener while she slept in the poem Inanna and Shukaletuda. The poem Inanna and Shukaletuda opens with a hymn to Inanna, in which she is praised as the planet, Venus. It then introduces Shukaletuda, a gardener who is terrible at his job. Except for one poplar tree, all of his plants die. Shukaletuda seeks guidance from the gods in his task. To his amazement, the goddess Inanna notices his single poplar tree and decides to rest beneath its branches. Shukaletuda undresses Inanna and rapes her while she sleeps.

When the goddess awakens and finds she has been raped, she becomes enraged and vows to bring her assailant to justice. In a flash of wrath, Inanna unleashes horrible plagues upon the Earth, turning water into blood. Shukaletuda, scared for his life, begs his father for help in escaping Inanna's anger. His father advises him to hide in the city, amid the crowds, where he will presumably fit in. Inanna searches the mountains of the East for her assailant but is unsuccessful. She then unleashes a series of storms and barricades all roads to the city, but she still can't find Shukaletuda, so she begs Enki for assistance, threatening to leave her temple in Uruk if he doesn't. Enki agrees, and Inanna soars "across the sky like a rainbow". Inanna eventually finds Shukaletuda, who tries in vain to make justifications for his crime against her. Inanna dismisses his excuses and murders him. The story of Shukaletuda has been identified as a Sumerian astral myth by theology professor Jeffrey Cooley, who claims that the movements of Inanna in the story match with the motions of the planet Venus. He further claims that as Shukaletuda was praying to the goddess, he was maybe looking toward Venus on the horizon.

Enki is the Sumerian god of water, knowledge, crafts, and creation -worldhistory.org

Inanna and Shukaletuda -mesopotamiangods.com -

One of the most interesting facts about Ancient Mesopotamia Goddess Inanna is that Inanna appears in more myths than any other Sumerian deity. She also had a disproportionately large number of epithets and variant names, second only to Nergal. Many of her mythologies involve her assuming the kingdoms of other gods. Enki, the god of wisdom, was said to have handed her the mes, which embodied the positive and negative qualities of civilization. She was also thought to have seized control of the Eanna temple from An, the god of the sky. Inanna, along with her twin brother Utu (later known as Shamash), was the enforcer of divine justice; she destroyed Mount Ebih for challenging her authority, unleashed her wrath on the gardener Shukaletuda after he raped her in her sleep, and tracked down and killed the bandit woman Bilulu in divine retribution for murdering Dumuzid. Ishtar begs Gilgamesh to be her consort in the classic Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh. When he refuses, she summons the Bull of Heaven, which kills Enkidu and forces Gilgamesh to confront his mortality.

The story of Inanna's descent into and return from the ancient Mesopotamian underworld, controlled by her older sister Ereshkigal, is her most renowned myth. When she enters Ereshkigal's throne room, the seven underworld judges find her guilty and execute her. Three days later, Ninshubur begs all the gods to return Inanna. Except for Enki, who sends two sexless beings to rescue Inanna, all of them deny her. They accompany Inanna out of the underworld, but the Galla, the underworld's guards, pull her husband Dumuzid down as her replacement. Dumuzid is eventually allowed to return to heaven for half of the year, while his sister Geshtinanna stays in the underworld for the other half, culminating in the seasonal cycle.

goldspur.ch

amateurexegete.com