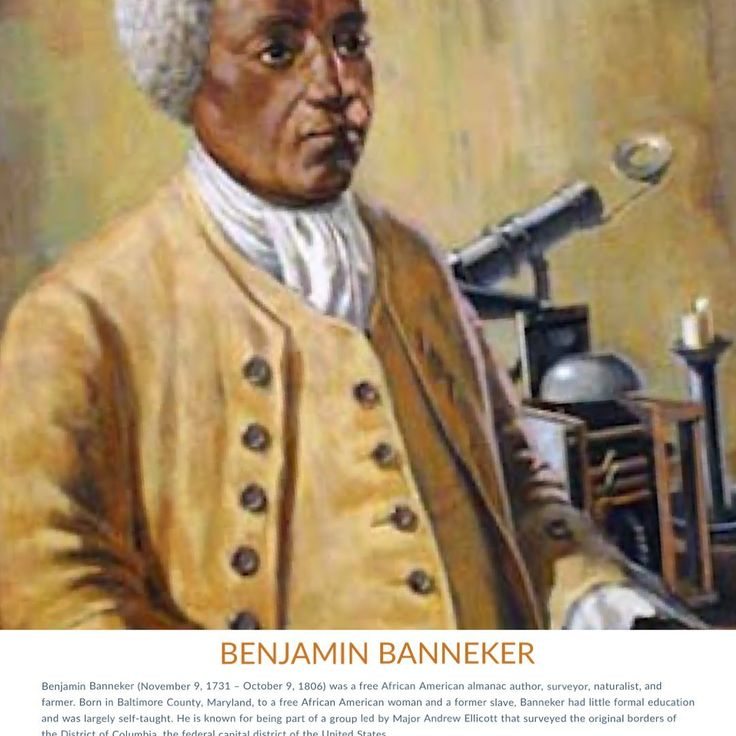

Top 8 Interesting Facts about Benjamin Banneker

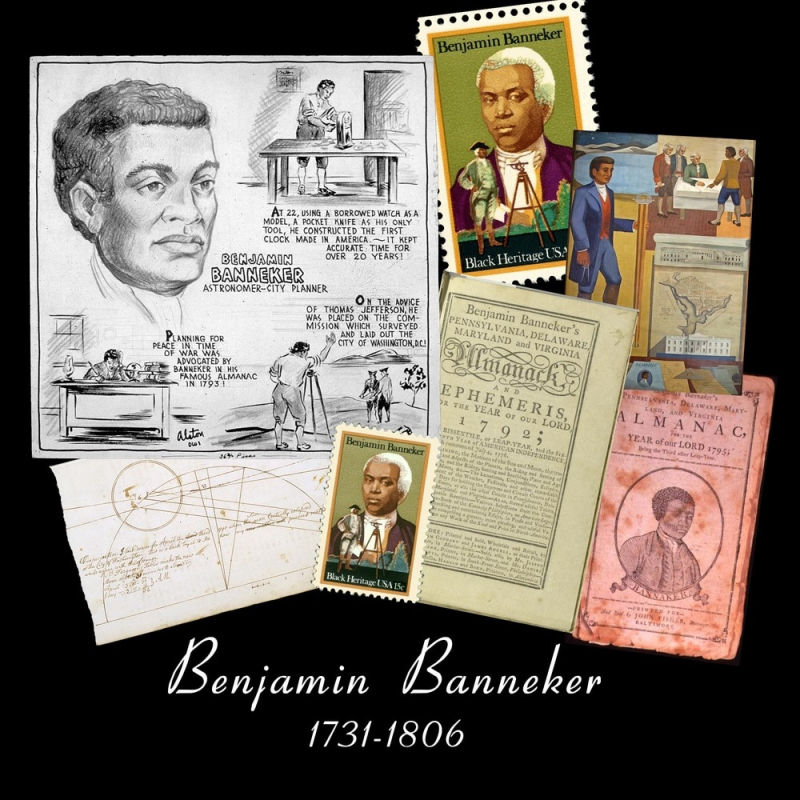

As a civil rights activist in American history, Benjamin Banneker, an African-American philosopher, is known for his exceptional and distinguished record of ... read more...compiling almanacs and playing an important role in defending the legal rights of slaves. In this article, Toplist has listed below some interesting facts about Benjamin Banneke that many readers did not know during his life.

-

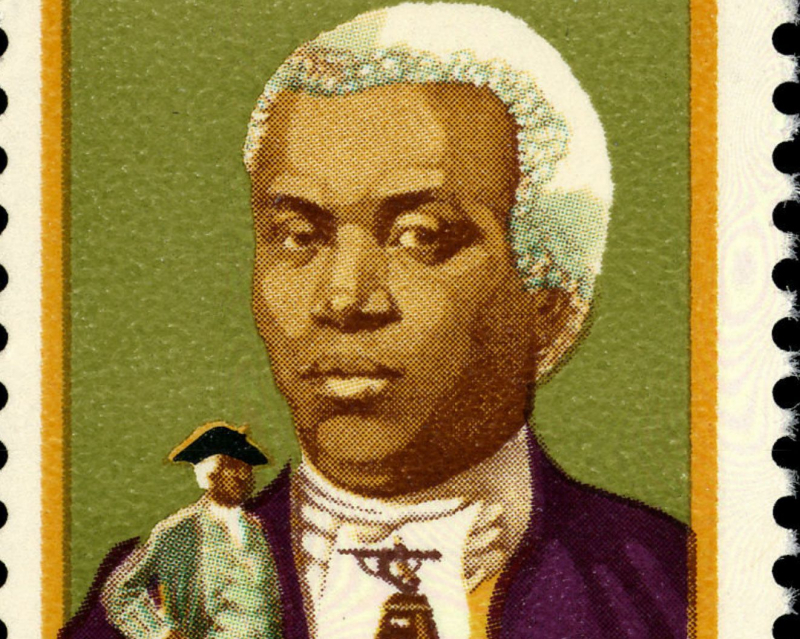

On November 9, 1731, Benjamin Banneker was born in Baltimore County, which is found in the state of Maryland's northern region. His father Robert was an ex-slave who bought his own freedom from slavery, while his mother Mary was a free African American. Several biographers assert that his mother Mary was a mulatto since she was the offspring of Molly Welsh, an Englishwoman, and Banneka, an African freed slave, even if this cannot be proven with confidence.

Banneker was a knowledgeable surveyor who developed his skills while working for the Ellicotts, a prominent Quaker family in Maryland. Benjamin Banneker, who is often regarded as America's first black scientist and civil engineer, was born free, which was unusual at a time when an estimated 750,000 black people lived in the country as slaves.

Banneker, a self-taught natural philosopher who later became an amateur mathematician and astronomer, contributed to the mapping of the District of Columbia, the nation's new capital, and wrote widely-read almanacs. His most audacious deed, nevertheless, was to publicly disagree with Thomas Jefferson on the subject of racism and slavery.

Jefferson made various attempts to gradually abolish slavery in the United States early in his political career. He devised a statute in Virginia in 1778 that forbade the importing of new slaves from Africa, and he put forth a bill to outlaw slavery in the expanding Northwest territory in 1784. These restrictions, he thought, would help phase out the slave economy over time.

Jefferson yet maintained his belief in the moral and social superiority of whites over blacks in spite of his reservations about the slave trade. In actuality, he sold and possessed more than 700 slaves directly. And there is evidence that Jefferson had a long-term relationship with Sally Hemings, one of his slaves, and had six children with her.

Photo: Monumental Surveyors

Photo: Scientific American -

The Patapsco River valley in rural Baltimore County was home to the 100-acre tobacco farm owned by the Banneker family. Benjamin lived almost his entire life and was reared here. As soon as he was old enough, he began assisting the family with farm work. Despite his reputation for academic prowess, Benjamin spent the majority of his life working as a farmer.

Banneker's early years were spent cultivating tobacco on his parents' 100-acre farm close to the banks of the Patapsco River with his family, which also included three sisters. His grandmother had taught him to read and write when he was little using a Bible she had imported from England, but his sole official education consisted of a few weeks or so spent attending a nearby Quaker one-room school.

In addition to becoming a voracious reader and mastering mathematics, Benjamin also became a voracious book borrower. He took pleasure in creating mathematical puzzles and deciphering those that others presented to him.

Photo: Audacy Video: TED-Ed -

A Christian sect known as Quakers first appeared in England around the middle of the 17th century. The Quakers are well recognized for their support of racial equality and their involvement in the anti-slavery movement. An interesting fact about Benjamin Banneker is that while he was a teenager, he grew close to Quaker Peter Heinrichs. Benjamin had access to Heinrichs' personal library. Heinrcihs' one-room school was occasionally attended by Benjamin as well. These were the only lessons he received in class, and he mostly learned astronomy and advanced mathematics through the voracious reading of books he borrowed.

Because they favored equal rights for everyone, regardless of race, creed, or caste, the Quakers gained popularity. Benjamin was granted access to Heinrichs' library and a book loan. He only ever studied and learned in this chamber, including everything he knew about advanced mathematics and astronomy. For Benjamin, borrowed books were a blessing.

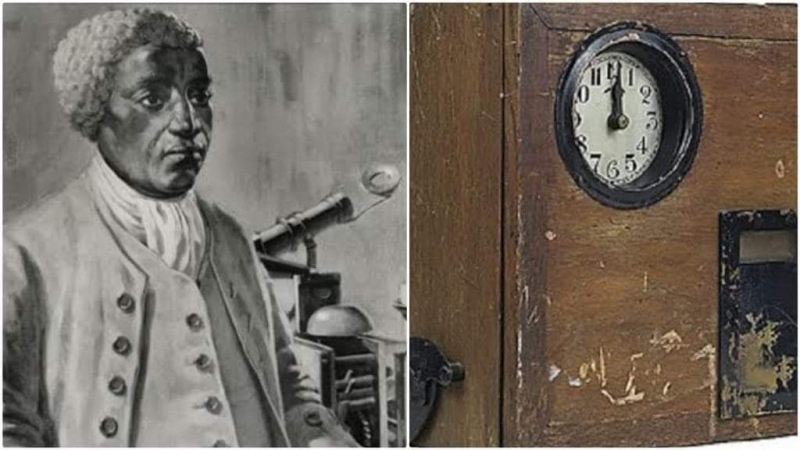

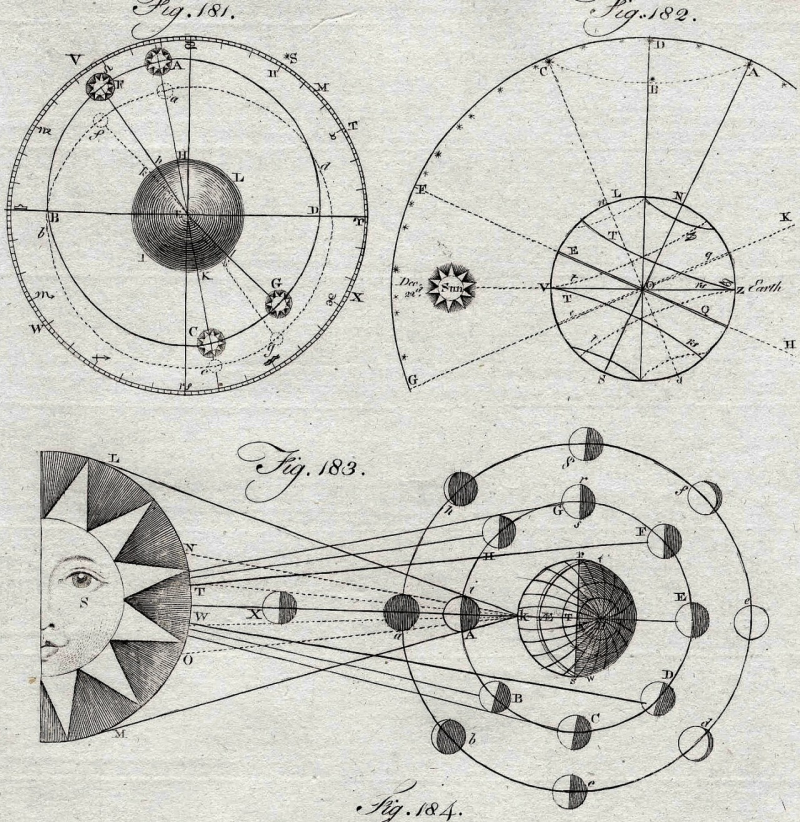

He quickly showed a special aptitude for maths. He constructed a wooden clock that kept accurate time when he was still a young man (possibly around age 20). George Ellicott, a Quaker and amateur astronomer whose family owned mills close by, urged Banneker to pursue astronomy as a field of study. Banneker started performing astronomical calculations as early as 1788, and he correctly foresaw a solar eclipse that took place in 1789. Banneker made more astronomical observations in 1791 while collaborating with Andrew Ellicott and others on the survey of the area that would become Washington, D.C.

Photo: Pinterest

Photo: Banneker Watches & Clocks -

According to PBS, Banneker had only "seen two timepieces in his lifetime—a sundial and a pocket watch" when he was 22 years old in 1753. Clocks weren't widely used in America at the time. Still, according to PBS, "Banneker built a striking clock almost entirely out of wood, based on his own plans and calculations, on the basis of these two mechanisms. Up until it was destroyed in a fire forty years later, the clock kept on ticking. The clock, which was made completely of hand-carved wooden components, attracted visitors from far and wide.

It is claimed that it was based on his memories of a pocket watch's mechanism. He must have thought of it as a mathematical puzzle as he meticulously carved each toothed wheel and gear from seasoned hardwood with a pocket knife. He used either a glass bottle cap or a metal can as a bell. The clock, which seems to have been the first in the area, attracted anyone who heard about it to his cabin to see it and hear it strike. Up until his passing, the clock ran well for more than fifty years. There is disagreement about whether it was the first wooden clock manufactured in America; various sources disagree, including the United States Postal Service, which claims Banneker was responsible. Whatever the circumstances, it was nonetheless a significant accomplishment that improved his intellectual standing.

It is notable for being the first clock constructed entirely in the United States and maintaining accurate time even after his passing in 1806. He was soon pushed to pursue astronomy, which he did exceptionally well in. He started performing astronomical calculations in 1788, and in 1789, he correctly predicted a solar eclipse that took place. From that point on, he started making additional astronomical observations and forecasting future solar eclipses by ten years.

Photo: Citizen NewsNG Video: NaturallyTeeCee -

The Quaker Ellicott family settled in Baltimore County and acquired property close to the Banneker farm. Benjamin had some background in astronomy, and George Ellicott, an Ellicott and an amateur astronomer offered him some books and tools to begin a more thorough investigation. Banneker foresaw the solar eclipse that took place in 1789 and began performing astronomical calculations as early as 1788. His accurate prediction went against those of more well-known astronomers and mathematicians.

A family from Ellicott relocated to Baltimore County and took up residence close to Banneker's home. They were both Quakers, and because George Ellicott was interested in astronomy, the two men became friends. George loaned books and tools to Benjamin, who used them to thoroughly research astronomy with keen enthusiasm. He predicted the solar eclipse of 1789 using astronomical calculations in the year 1788. A crucial feature about Benjamin Banneker is that although many of the leading astronomers and mathematicians of his time condemned him, his accurate forecast won him praise.

Banneker lived most of his life on the 100-acre farm his family owned outside of Baltimore. Banneker started publishing an annual almanac in 1791 after teaching himself astronomy. He noted when the Sun, Moon, and stars would be visible in the sky each day for the upcoming year in it. European scientists liked his almanacs. Additionally, Banneker published articles and pamphlets that opposed both slavery and war.

One of the interesting facts about Benjamin Banneker is that he acquired advanced mathematics from borrowed textbooks and taught himself astronomy by studying the stars. Banneker started performing astronomical calculations in 1789, which allowed him to accurately predict a solar eclipse. His estimate, which was made well before the cosmic occurrence, went against what more eminent mathematicians and astronomers had predicted.

Photo: Magic Transistor - Tumblr Video: Biography -

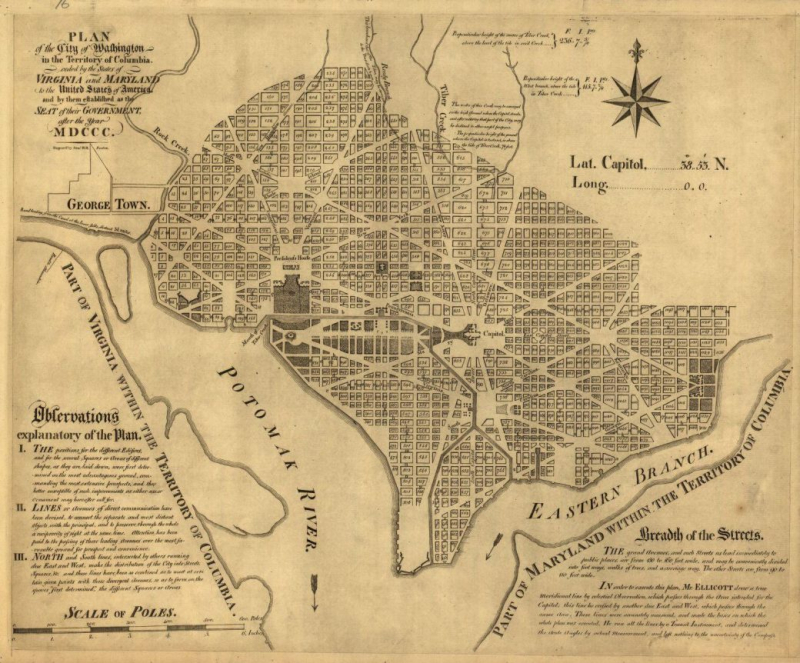

There was just as much discussion about the size and design of the new federal capital when the United States ratified the Constitution in 1789 as there was about the other issues facing the young country. Some feared that the nascent republic's cohesiveness would be destroyed before it even got off the ground due to the ferocious debate about where it should be established, whether it be in Boston, Philadelphia, or New York.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant wrote to George Washington asking to be hired to design the federal city even before the site of the new federal capital specified in the Constitution was chosen. When Congress passed the Residence Act of 1790, which established the Potomac River as the permanent location for the capital, he received his wish.

Benjamin Banneker was chosen and included in the team, or the District of Columbia Commission, that Major Andrew Ellicott led to survey the site for the US capital city in 1791. It then changed its name to Washington, DC. It was Benjamin's responsibility to make astronomical calculations and observations. Unfortunately, his condition prevented him from finishing his task.

Banneker had to recreate the entire city plan from memory after Pierre Charles L'Enfant resigned and left the commission, but it saved him a lot of time. Being a member of that group allowed Banneker, a free black man living in a country where slavery was still legal, to use his knowledge and abilities to refute the notion that blacks were a less-than-equal race. The degree of Banneker's contributions to the planning and construction of the US capital may be contested in some quarters, but it is well known that he was a key player in the massive undertaking.

Photo: White House Historical Association

Photo: ABNA Engineering -

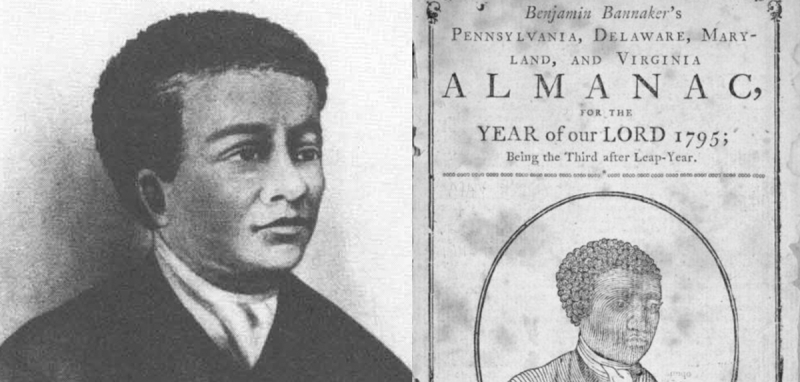

According to the Library of Congress, Banneker had a clear aptitude for mathematics and machinery despite having little formal education and scientific expertise. The Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia Almanac and Ephemeris, which he published from 1791 to 1802, was a product of his expertise as an accomplished astronomer.

According to the Library of Congress, "Banneker spent the majority of his life on his family's 100-acre farm outside of Baltimore." "There, he acquired advanced mathematics from borrowed textbooks and taught himself astronomy by studying the stars."

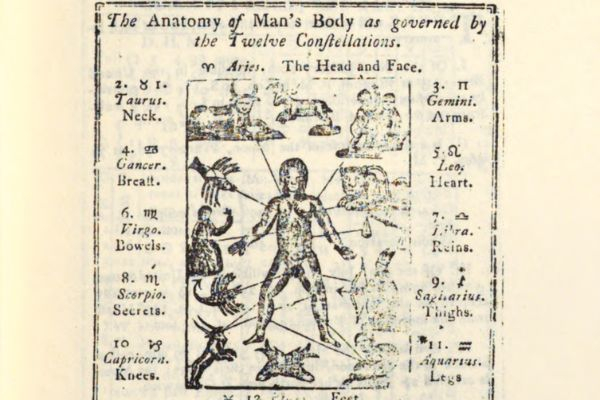

As a gentleman farmer, Banneker had lots of chances to observe the environment. The Almanac and his other books contain many such insights. His almanac supplied medical advice, documented the tides, and forecast eclipses and other celestial events, according to the Library. According to PBS, it "also incorporated commentary, literature, and fillers that had a political and humanitarian purpose," such as a line from a poem opposing slavery in the 1793 version.

The Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia volumes of the Almanacs and Ephemeris series were written by Benjamin Banneker. His series of almanacs included details on literary works, medications, and astronomical observations. Between 1792 and 1797, the almanacs were released annually and distributed to 6 cities and 4 states. An interesting fact about Benjamin Banneker is that the success of the series helped to make him famous and well-liked. They not only provided astronomical facts but also his writings, literary works, as well as tidal and medical data. They increased his notoriety and were a commercial success.

Photo: Farmers' Almanac

Photo: Smithsonian Magazine -

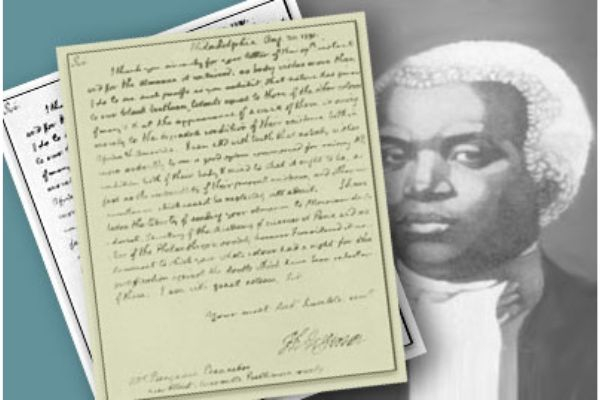

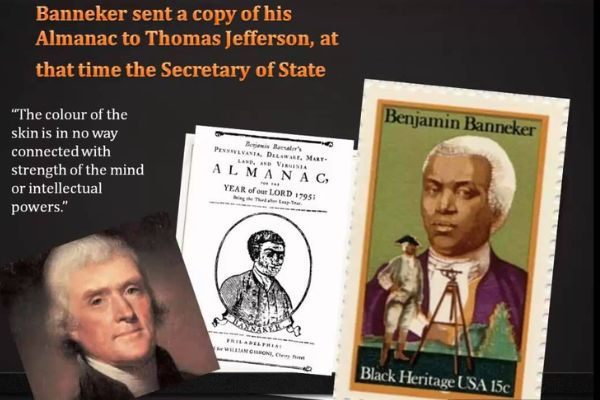

At the age of 59, Banneker wrote a letter to Thomas Jefferson, who was serving as secretary of state for the United States at the time. The letter chastised Jefferson for having slaves and asked him to strive for the advancement of African Americans. It also had a handwritten manuscript of Banneker's 1792 almanac.

Banneker wrote that his "Sympathy and affection for [his] brethren" led him "unexpectedly and unavoidably" to take the opportunity to condemn endemic prejudice and the "groaning captivity and cruel oppression" of slavery. He claimed that his intention was simply to direct to Jefferson "as a present, a copy of an Almanack which I have calculated for the Succeeding year." Banneker contended that he had a moral obligation to address the secretary of state on this subject because he was aware of a serious injustice. Instead of speaking for all slaves, he did so as a more privileged "brother" of slaves who felt compelled to utilize his skills to further the interests of his race. Banneker attacked the system, which he dubbed "that State of dictatorial thraldom, and horrible captivity," highlighting the contradiction between the rhetoric of equality stated in the Declaration of Independence and the actuality of slavery.

Jefferson responded by praising Banneker's accomplishments and using them as evidence to dispel any racial prejudice. In the British House of Commons, abolitionists like William Wilberforce and others praised Banneker's efforts.

Photo: Black Then

Photo: Pinterest