Top 10 Interesting Facts about Charles Lindbergh

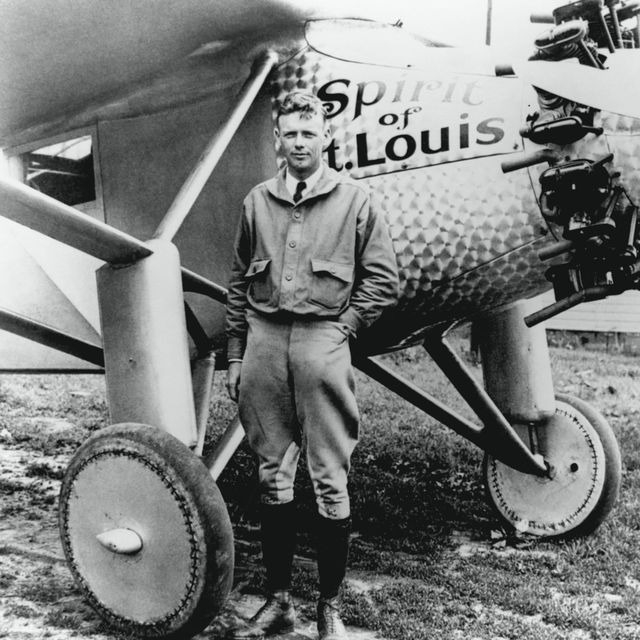

Charles Augustus Lindbergh was an American pilot, military officer, novelist, inventor, and activist. At the age of 25, he made history by being the first solo ... read more...pilot to complete a nonstop flight from New York to Paris. Besides that, there are many other interesting facts about Charles Lindbergh.

-

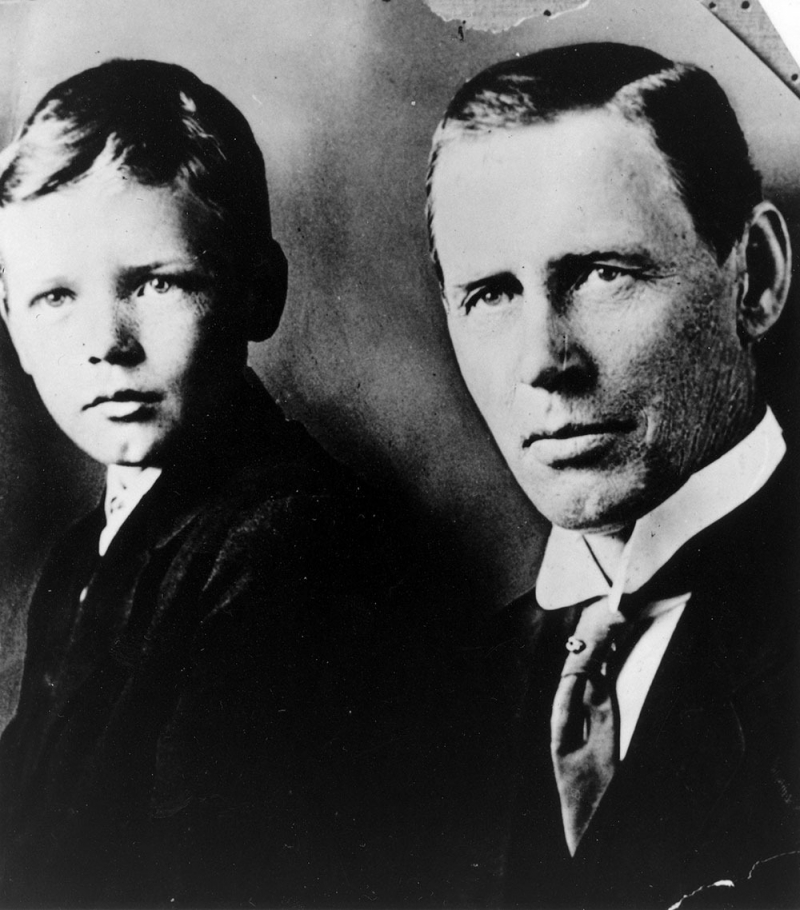

When Charles Lindbergh was four years old, his father, Charles August Lindbergh was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives by Minnesota's Sixth Congressional District. He would hold office in Congress for five terms, where he established a reputation for taking independent positions and vehemently opposing the Federal Reserve System.

In 1914, when World War I broke out in Europe, Lindbergh opposed strongly American involvement. He was defeated in his bid for the United States Senate in 1916 by a rival who openly supported American participation in Europe. Lindbergh was one of just 14 lawmakers to vote against arming American commerce ships in March 1917.

Against incumbent Joseph A. A. Burnquist, a Republican, Lindbergh ran for governor of Minnesota in 1918. He was supported by the Farmers Nonpartisan League, which advocated for government ownership of some agricultural businesses such as mills, plants, and grain elevators, supported Lindbergh. Thousands of supporters attended many of his campaign addresses. However, because of his opposition to American involvement in World War I and his affiliation with the Socialistic Farmers Nonpartisan League, Lindbergh came under fire from the press, and protesters frequently threw rocks and eggs at him. Charles Lindbergh served as his father's driver, and "never forgot the hostile crowds that harassed his father, or the way the press derided him."

Photo: Minnesota Historical Society

Photo: Wikipedia -

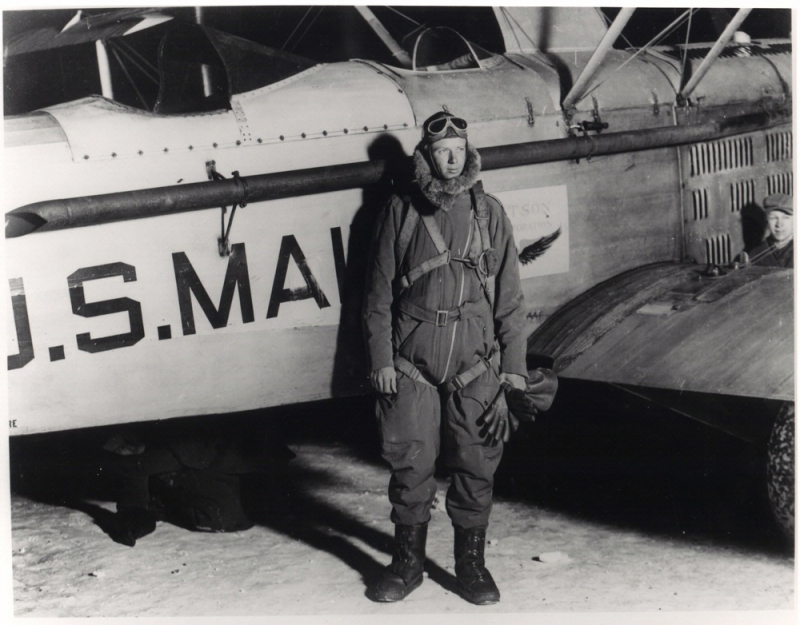

Charles Lindbergh spent two years as an aerial daredevil and traveling stuntman after learning to fly at the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation in Lincoln. The youthful pilot dazzled spectators with daring displays of wing-walking, parachuting, and mid-air plane changes during "barnstorming" excursions through the American heartland.

His first solo flight and return to the skies didn't occur until May 1923 at Souther Field in Americus, Georgia, a former Army flight training facility, when he purchased a Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" biplane that had been left over from World War I. Despite the fact that Lindbergh hadn't touched an aircraft in almost six months, he had already quietly concluded that he was prepared to fly alone. Lindbergh flew solo for the first time in the Jenny, that he had just purchased, after a half-hour of dual time with a pilot who was stopping by the field to pick up another surplus JN-4.

After another week or so of "practicing" at the field, Lindbergh took off from Americus for his first solo cross-country flight, traveling 140 miles to Montgomery, Alabama. This gave him five hours of "pilot in charge" time. He then spent the majority of the remaining months of 1923 barnstorming virtually constantly under the alias "Daredevil Lindbergh." This time, unlike the year before, Lindbergh served as the pilot and sailed in his "own ship". This is one of the interesting facts about Charles Lindberg.

Photo: Esquire Source: Studies Weekly -

One of the interesting facts about Charles Lindberg is that he was not the first pilot to cross the Atlantic. The journey crossings of the Atlantic were accomplished by scores of other pioneering pilots in the years before to Charles Lindbergh's journey from New York to Paris.

Eight years previously, British pilots John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown accomplished the first nonstop transatlantic flight in a modified Vickers Vimy IV bomber (1,890 miles or 3,040 kilometers, which is much less than Lindbergh's 3,600 miles or 5,800 kilometers voyage). On June 14, 1919, they departed St. John's, Newfoundland, and they arrived in Ireland the following day. In the same period, Augustus Post, secretary of the Aero Club of America, approached Raymond Orteig, a French-born hotelier in New York, and persuaded him to offer a $25,000 prize for the first successful nonstop transatlantic flight specifically between New York City and Paris (in either direction) within five years of the club's founding.

Most traveled in stages or with lighter-than-air dirigibles. However, the fact that Charles Lindbergh accomplished this feat alone and between two important international cities was more significant than he was the first person to fly over the Atlantic.

Photo: Madison

Photo: Disciples of Flight -

The main difficulty Charles Lindbergh faced on his transatlantic trip, except navigating the hazy Atlantic, was just staying awake. Nine hours into his 33-hour of the nonstop journey from New York to Paris, Charles Lindbergh wrote in his memoirs that he had to overcome the strong urge to fall asleep. It's one of the most interesting facts about Charles Lindberg. He was so tired that he would occasionally close his eyes and drift off, and from lack of sleep, he even had hallucinations.

In an effort to stay awake, Charles Lindbergh went so far as to buzz the ocean's surface, but 24 hours into the flight, his lack of sleep caused him to go delirious. Later, he described seeing "vaguely delineated figures, transparent, moving, riding weightless with me in the plane" and "fog islands" developing in the water below.

Even more, Lindbergh insisted that the ghostly figures spoke to him and gave him advice for his travels. After a little while, the hallucinations subsided, and a few hours later, the fatigued pilot touched down in Paris to the cheers of more than 150,000 onlookers.

Photo: Mental Floss Source: lagarchivist -

On March 1, 1932, the Lindberghs' nurse, Betty Gow, discovered that 20-month-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was separated from his mother, Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Gow then informed Charles Lindbergh, who rushed to the child's room right once and discovered a ransom note there in an envelope on the ledge. The note had poor handwriting and language. With the help of the family butler, Olly Whateley, Lindbergh searched the house and grounds with a rifle. They discovered a baby's blanket, bits of a wooden ladder, and prints in the ground beneath the baby's window.

On May 12, a delivery truck driver named Orville Wilson and his assistant William Allen pulled to the side of the road a little more than 4.5 miles (7.2 km) south of the Lindbergh residence in the nearby Hopewell Township hamlet of Mount Rose. Allen found a toddler's body after entering a forest of trees to relieve himself. The right foot's overlapping toes and homemade clothing allowed Gow to identify the infant as the missing child. The child of Charles Lindbergh appears to have died from a strike to the head.

Carpenter Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German immigrant, was detained for the crime in September 1934. He was convicted guilty of first-degree murder during a trial that ran from January 2 to February 13, 1935, and he was given the death penalty. He maintained his innocence despite being found guilty, but all of his attempts to appeal were unsuccessful, and on April 3, 1936, he was put to death in the electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison.

Photo: FBI Source: Weird History -

Charles Lindbergh became one of the world's most well-known people due to his transcontinental flight. The headline "Lindbergh Does It!" appeared above the fold on the front page of The New York Times. About 1,000 people gathered around his mother's house in Detroit. He received many job offers from businesses, think tanks, and institutions, as well as numerous requests to be interviewed by newspapers, magazines, and radio programs.

He rode in more than a thousand kilometers of parades, received millions of messages from enthusiastic followers, and even received the Medal of Honor. Nevertheless, it didn't take long for "The Lone Eagle" to resume its daring flight.

As part of a diplomatic tour to Latin America, he flew "The Spirit of St. Louis" alone and nonstop from Washington, D.C., to Mexico City in December 1927. Charles Lindbergh met Anne Morrow, the daughter of American Ambassador Dwight Morrow, while he was in Mexico, and the two soon got married. Later, Anne developed into Lindbergh's dependable copilot and radio operator. The two of them flew pioneering missions, including one in 1931 from the United States to Japan and China.

Photo: NPR

Photo: JFK Library -

Peter planned a weekend retreat for rocket enthusiasts not long after finishing The Spirit of St. Louis. To discuss reusable rockets and a personal route to space, he invited scientists, financiers, engineers, and space enthusiasts.

Charles Lindbergh was also a well-known supporter of early aviation. Via his collaboration with Robert Goddard, the so-called "father of modern rocketry," he also contributed to planting the seeds of the space program. In late 1929, Lindbergh first became aware of Goddard's research on liquid-fueled rockets, and the two quickly grew close. In 1930, Lindbergh assisted Goddard in obtaining an endowment from Daniel Guggenheim, enabling Goddard to increase his research and development. Lindbergh remained a significant supporter of Goddard's efforts throughout his life.

Charles Lindbergh became Goddard's greatest supporter after becoming convinced that his work may one day make it possible to travel to the moon. He even persuaded millionaire Daniel Guggenheim to give the physicist $100,000 in funding. The innovations made by Goddard would subsequently be crucial to the creation of early missiles and space exploration. "You have made Robert Goddard's dream a reality", Lindbergh wrote in a letter to the astronauts after Apollo 8 became the first manned space mission to orbit the moon in 1968.

Photo: Pioneers of Flight

Photo: The Pietist Schoolman -

The first "artificial heart" was created in 1935 with the collaboration of Charles A. Lindbergh and Alexis Carrel, a Nobel prize-winning French scientist and surgeon. Although there is a misnomer by today's standards, Lindbergh and Carrel's invention preserved animal organs after they had been removed.

Carrel co-invented a method to preserve tissue, and Lindbergh created a perfusion pump in 1931 that circulated fluid through a section of an animal organ to keep it alive and functional for at least a month without infection. The invention of the pump, which was lauded as medical innovation, paved the door for the creation of the first real artificial organs.

Three vertical glass chambers made up the effective "artificial heart." The organ was kept in an aseptic, or sterilized, a condition in the top chamber. The third or bottom chamber, which served as a reservoir for Carrel's synthetic blood made of oxygen and nitrogen, was connected to the organ's artery by glass tubing. The middle chamber served as a leveler. Charles Lindbergh and Carrel revealed that numerous animals' glands, spleens, livers, hearts, and kidneys had been preserved in June 1935.

Photo: Biography

Photo: Star Tribune -

Due to his opposition to World War II and his sympathy towards Nazi Germany in the late 1930s and early 1940s, Lindbergh's once reputation suffered greatly. Charles Lindbergh had visited Germany numerous times in the 1930s to examine its air force, and he returned home certain that the Luftwaffe was strong enough to dominate the rest of Europe.

He emerged as one of the most outspoken opponents of American involvement in the fight, making his case for isolationism in scores of public speeches and radio broadcasts in which he also criticized President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Jewish-owned media outlets.

Many started calling the former hero an anti-Semite and a traitor as the United States drew closer to war. After Pearl Harbor was bombed, Lindbergh gave up his cause and wanted to join the military, but President Roosevelt, who in private referred to the aviator as a Nazi, prevented him from doing so. Later, Charles Lindbergh worked as a test pilot and an aviation advisor before going to the Pacific Theater of the war as an observer. He finally flew almost 50 combat flights while being a civilian in his official capacity, even shooting down a Japanese fighter jet.

Photo: The Washington Post

Photo: All that's interesting -

Charles Lindbergh started having long-term affairs with three women starting in 1957 while still being married to Anne Morrow. With hatmaker Brigitte Hesshaimer (1926–2001), who had once resided in the small Bavarian village of Geretsried, he had three children. He had two kids with Mariette, a painter who lived in Grimisuat, and her sister. Along with Valeska, an East Prussian aristocrat who served as his personal secretary in Europe and resided in Baden-Baden, Lindbergh also had a son and a daughter (born in 1959 and 1961, respectively). Each of the seven kids was born between 1958 and 1967.

Charles Lindbergh wrote to each of his European lovers ten days before he passed away, pleading for them to keep his affairs with them a complete secret even after his passing. None of the three women—none of whom ever got married—managed to hide their relationships from their children, who—during his lifetime and for almost ten years after his passing—had only known their father by the alias Careu Kent and had only ever seen him when he paid them a quick visit once or twice a year.

Brigitte's daughter Astrid, however, came to the correct conclusion after reading a magazine article about Lindbergh in the middle of the 1980s; she subsequently uncovered photographs and more than 150 love letters that Lindbergh had written to her mother. She published her discoveries after Brigitte and Anne Lindbergh passed away, and DNA tests in 2003 proved that Lindbergh was the father of Astrid and her two siblings.

Photo: Biography

Photo: Pinterest