Top 9 Interesting Facts about Claude Debussy

Claude Debussy is one of the most well-known composers in the history of classical music. Toplist will share some interesting facts about Claude Debussy.... read more...

-

Although Debussy is well known for his tranquil music, his personal life, particularly as it related to women, was anything but. He had a number of well-known affairs and ended his marriages to other women suddenly. It's one of the interesting facts about Claude Debussy that we want to mention. Once, author Marcel Dietschy penned: “There was a woman at each crossroad of Debussy’s life. Certainly women of all ages seemed fascinated by him, and they attached themselves to him like ivy to a wall.”

In the 1890s, as he established his reputation, Debussy shared a home in Montmartre with a woman by the name of Gabrielle DuPont. After working for DuPont for more than ten years, he abruptly told her to find another place to live so he could wed model and seamstress Rosalie Texier. Due to his sympathy for Gaby and women in general, Debussy lost friends, and DuPont shot herself but survived and vanished into obscurity.

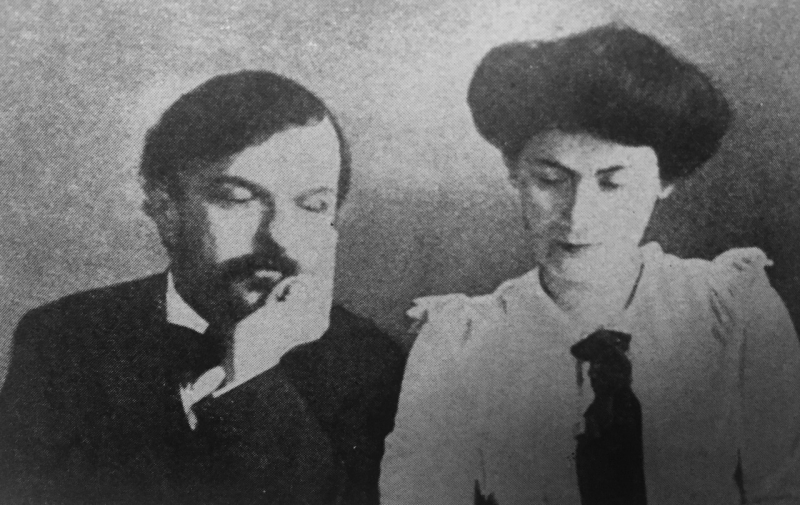

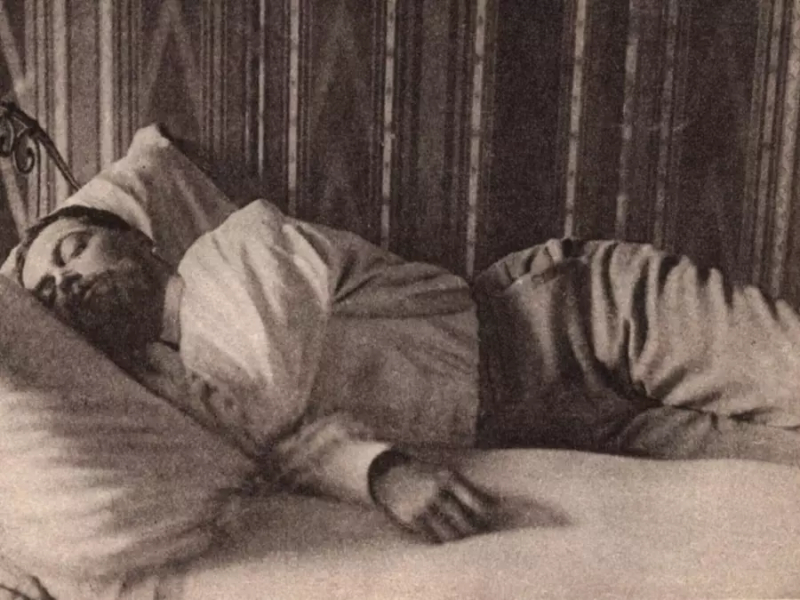

Rosalie Texier, however, allegedly did not satiate Debussy's intellectual curiosity, so in the summer of 1904, after nearly 5 years of marriage, he sent her home from their seaside getaway (and later gave her the written okay to divorce him) and picked up another woman named Emma Bardac that same day from the train station (pictured with Debussy above). Claude Debussy had his only child, Claude-Emma Debussy, with Emma in 1905. He remained with her for the rest of his life and wed Bardac in 1908.

Photo: Classic FM - Claude Debussy and Emma Bardac

Photo: Composers Doing Normal Shit - Claude Debussy and Rosalie Texier -

France's Claude Debussy was a composer. Although he vehemently rejected the term, he is occasionally regarded as the first Impressionist composer. He was one of the composers who had the most impact in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

He was reportedly born into a low-income family with little exposure to the arts. However, his parents believed he would become a piano virtuoso because of how much he enjoyed playing the piano. Debussy demonstrated sufficient musical talent to be accepted at the age of 10 to the Conservatoire de Paris, France's top music school. While at college, he developed a unique music taste and created innovative compositions, much to the displeasure of the professors. Despite the conservative professors at the Conservatoire's disapproval, he initially studied the piano but eventually discovered his passion for creative composition. Unfortunately, the criticism of his manner prevented him from receiving the help he needed to advance his skills quickly. He eventually achieved the fame for which he is known, but not without first beating the odds and developing his craft. He spent many years honing his mature style, and he was almost 40 years old when Pelléas et Mélisande, his sole opera, brought him international acclaim in 1902.

Photo: Rete Toscana Classica

Photo: UNA | Universidad Nacional de las Artes -

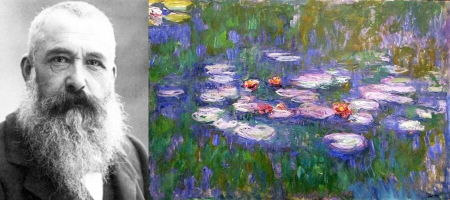

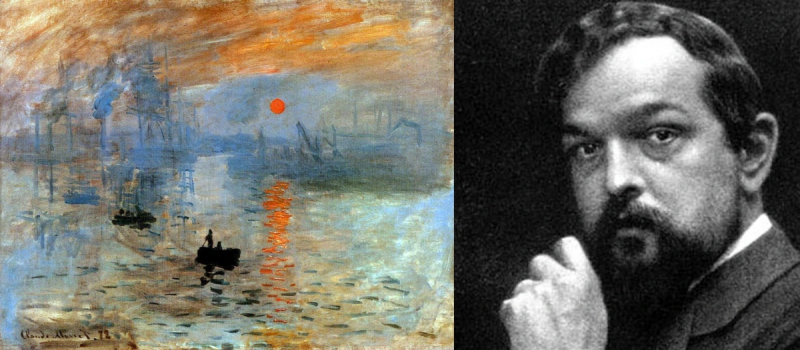

It has been hotly contested, both then and now, whether or not Debussy and the music he influenced qualify as "Impressionist." According to art critic Richard Langham Smith, the term "Impressionism" was initially used to describe a late 19th-century French painting movement in which the emphasis is on the overall impression rather than on outline or clarity of detail, as in the paintings by Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and others. These paintings frequently feature scenes that are bathed in reflected light. The phrase was later applied to Debussy's and other composers' works that were "concerned with the representation of landscape or natural phenomena, particularly the water and light imagery dear to Impressionists, through subtle textures suffused with instrumental color," according to Langham Smith.

Although Debussy vehemently objected to the term "Impressionism" being used to describe his (or anyone else's) music, it has been associated with him ever since the Conservatoire's assessors offensively used it to describe his early composition Printemps. The piano pieces "Reflets dans l'eau" (1905), "Les Sons et les parfums tournent dans l'air du soir" (1910), and "Brouillards" (1913) are just a few examples of Debussy's nature-inspired compositions, according to Langham Smith, who also suggests that Debussy's use of brushstrokes and dots is similar to that of Impressionist painters. Although Debussy claimed that anyone who used the term (whether in reference to music or painting) was a fool, some Debussy scholars have adopted a less rigid stance. La mer is described by Lockspeiser as "the best orchestral example of an Impressionist work," and more recently, Nigel Simeone writes in The Cambridge Companion to Debussy, "It does not seem overly far-fetched to see a parallel in Monet's seascapes."

Photo: Chasing the Chords - First Impressionist: The Style and Character of Claude Debussy

Photo: Colorado Public Radio - Musical Impressionism Started With Claude Debussy's 'Prelude To The Afternoon Of A Faun' -

Rudolph Reti, a critic, listed six characteristics of Claude Debussy's music in 1958, which he asserted "established a new concept of tonality in European music": the frequent use of lengthy pedal points – "not merely bass pedals in the actual sense of the term, but sustained 'pedals' in any voice"; glittering passages and webs of figurations which distract from the occasional absence of tonality; frequent use of parallel chords which are "in essence not harmonies at all, but rather 'chordal melodies', enriched unisons", described by some writers as non-functional harmonies; bitonality, or at least bitonal chords; use of the whole-tone and pentatonic scales; and unprepared modulations, "without any harmonic bridge". Reti comes to the conclusion that Debussy achieved this by combining harmonies, however distinct from those of "harmonic tonality," with a monophonic-based "melodic tonality."

Debussy and his former instructor Guiraud had talks in 1889 during which the pianist explored various harmonic possibilities. Maurice Emmanuel, a Guiraud student who was younger, took note of the conversation and Debussy's improvised chordal piano pieces. Some of the components mentioned by Reti may be heard in the chord progressions Debussy plays. They could also be a sign of Satie's 1887 Trois Sarabandes' impact on Debussy. During this chat, Debussy also improvised a series of whole tone harmonies that may have been influenced by the music of Glinka or Rimsky-Korsakov, which was starting to gain popularity in Paris at the time. Guiraud overheard Debussy say to him: "There is no theory. You have only to listen. Pleasure is the law!" – although he also conceded, "I feel free because I have been through the mill, and I don't write in the fugal style because I know it."

Photo: Encyclopedia Britannica - Claude Debussy Video: Five Minute Mozart -

The ideal text to adapt to music was a question posed to Claude Debussy in the journal "Musica" in 1911. The composer proclaimed his choice for rhythmic prose after skeptically illustrating a number of options, adding that the composer should create his text. Debussy published 56 songs, but of those, he issued no less than 18 set poetry by Paul Verlaine. He did, after all, arrange numerous of his words to music.

Debussy used Verlaine's maxim "Music above all else, and for that picked the irregular, nebulous and dissolving better into the air" and turned it into a literary reality. This artistic affinity between the two authors has been extensively analyzed. Before he traveled to Rome or became familiar with the music of Wagner, Debussy attempted two versions of Clair de Lune, with the first setting dated from between 1882 and 1884.

Your soul is a chosen landscape

Where charming masquerades and dancers are promenading,

Playing the lute and dancing, and almost

Sad beneath their fantastic disguises.

While singing in a minor key

Of victorious love, and the pleasant life

They seem not to believe in their happiness

And their song blends with the moonlight,

With the sad and beautiful moonlight,

Which sets the birds in the trees dreaming,

And makes the fountains sob with ecstasy,

The slender water streams among the marble statues.

But let's not forget that Verlaine and Claire de lune also served as the inspiration for the renowned Suite bergamasque, which properly featured "Clair de lune" in the third movement.Video: Matthew Thompson - Debussy 1892 Clair de lune Video: CHANNEL 3 YOUTUBE - Clair de Lune -

The five-act opera Pelléas et Mélisande features Claude Debussy's music. The same-named symbolist drama by Maurice Maeterlinck served as the inspiration for the French libretto. On April 30, 1902, the Opéra-Comique gave it its world premiere performance in Paris at the Salle Favart under the direction of André Messager, who had played a key role in convincing the Opéra-Comique to produce the opera. Jean Périer sang as Pelléas and Mary Garden as Mélisande. Being the only opera Debussy ever finished, it is regarded as a major achievement in 20th-century music.

There is a love triangle in the story. Mélisande, a strange young woman, is discovered by Prince Golaud stranded in a jungle. He marries her and returns her to his grandpa, King Arkel of Allemondepalace. ,'s Here, Mélisande is envious as she develops a close bond with Golaud's younger half-brother Pelléas. To learn the truth about Pelléas and Mélisande's relationship, Golaud goes above and beyond, even ordering his own kid, Yniold, to spy on the pair. Pelléas makes the decision to leave the castle, but he makes plans to see Mélisande one more time. They then make their love-confession official. Golaud comes outside after overhearing their conversation and murders Pelléas. After giving birth to a daughter, Mélisande passes away soon after, with Golaud still pleading with her to tell him "the truth."

Pelléas et Mélisande has continued to be routinely produced and recorded throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries despite its original criticism.Video: Claude Debussy - Pelléas et Mélisande

Photo: Teatro Regio Parma - Pelléas et Mélisande -

When Debussy was named a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur in 1903, the public acknowledged his status. However, the following year, a controversy involving another aspect of his personal life dealt severe damage to Debussy's social position. Raoul Bardac, the son of Emma, the wife of the Parisian financier Sigismond Bardac, was one of his students. Debussy was immediately attracted to his mother once Raoul introduced his instructor to her. She was sophisticated, witty in conversation, a talented vocalist, and unconcerned with marital fidelity because she had been Gabriel Fauré's mistress and inspiration a few years before.

On July 15, 1904, Debussy sent Lilly to her parents' residence at Bichain in Villeneuve-la-Guyard and then took Emma away, residing covertly in Jersey and Pourville in Normandy. On August 11, he wrote to his wife from Dieppe, informing her that their marriage was terminated but leaving out any mention of Bardac. He settled down on his own when he got back to Paris, renting a place in a separate district. Lilly Debussy shot herself in the chest with a handgun on October 14, five days before their fifth wedding anniversary, but she was saved and the bullet was left in her vertebrae for the rest of her life. Due to the subsequent controversy, Bardac's family had to renounce her, and Debussy also lost a lot of close friends including Dukas and Messager. His already strained relationships with Ravel got worse when the latter joined other ex-Debussy acquaintances in making contributions to a fund to aid the abandoned Lilly.

May 1905 saw the divorce of the Bardacs, Debussy and Emma, who was now pregnant, left for England because they could not stand the animosity in Paris. In July and August, they remained at the Grand Hotel in Eastbourne, where Debussy revised the La Mer symphonic sketches' proofs while also celebrating his divorce on August 2. Following a brief trip to London, the couple returned to Paris in September and purchased the property that would serve as Debussy's residence for the remainder of his life in a courtyard neighborhood off Avenue du Bois de Boulogne (now avenue Foch).

Photo: Classic FM - Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

Photo: GoHighBrow -

One of the interesting facts about Claude Debussy, he was already fighting his battle against colon cancer. Debussy began experiencing acute rectal pain by the year's end of 1908, and he soon started experiencing everyday bleeding. Early in 1909, Debussy writes to his publisher Jacques Durand on his doctor's advice to increase his exercise routine and switch up his diet. Debussy continued to endure grueling exams and unfathomable torment, but it wasn't until the summer of 1915, six years later, that he received a formal diagnosis. Life for Debussy and his family got significantly more difficult as the war began its second year. Food and fuel shortages, as well as a constant rise in price, making it harder and harder to make a livelihood. “It is almost impossible to work,” Debussy wrote, “to tell the truth, one hardly dares to, for the asides of the war are more distressing than one imagines. I am just a poor little atom crushed in this terrible cataclysm.”

In addition, his condition was developing in a terrifying way. Debussy had colostomy surgery and radiation therapy on December 7, 1915. Debussy wrote on June 8, 1916, when he was unable to work and extremely sad.

Debussy took heart after finding inner strength and started to write more music than he had in years. At the composition's debut on May 5, 1917, Debussy mustered the courage to play the piano portion of his Sonata No. 3 for Violin and Piano. A scholar writes, “reading Debussy’s letter from his last years, all the while contemplating the degree of almost endless suffering and ongoing physical deterioration is itself a painful experience. And yet he soldiered on, displaying precisely the sort of spirit and courage often attributed to those fighting a terminal disease.”

Photo: Last.fm

Photo: Last.fm -

A fleeting glimmer of optimism appeared in June 1916 when a radium therapy appeared to promise a recovery. However, the treatment had serious side effects. The "interesting ore," as he put it, did not go down well with him. Debussy was practically in an artificial coma, had stopped working, and both his wife and kid contracted the mumps in 1916. There was never a moment of calm; the barracks' trumpets nearly drove Debussy insane, and the rain sounded like a million small dwarven drums. Then, on March 23, 1918, the Germans launched an attack on Paris using the so-called "Paris Gun," a weapon created by the company Krupp, pounding the city from a distance with some 800 grenades.

Debussy was too frail to find refuge in the cellar. He was subjected to the assault for two days before succumbing on March 25, 1918, just before midnight. René Valléry-Radot, a friend of his, remembers it like way: "He was emaciated, staring off into the distance. His hands were shaking. He smiled at me as if waking from a dream, and spoke a few loving words. Then the fog descended over his soul once more."Three days later, the burial was to take place in the Père Lachaise artists' cemetery, but the funeral procession transformed into a risky obstacle course. The casket had to be carried around the entire city since just 20 mourners were ready to brave the streets. He was taken "under the booming and thunder of German artillery fire" to his final burial place.

Photo: takt1 - Claude Debussy's funeral

Photo: Wikipedia - Debussy's grave