Top 8 Interesting Facts about Edward Jenner

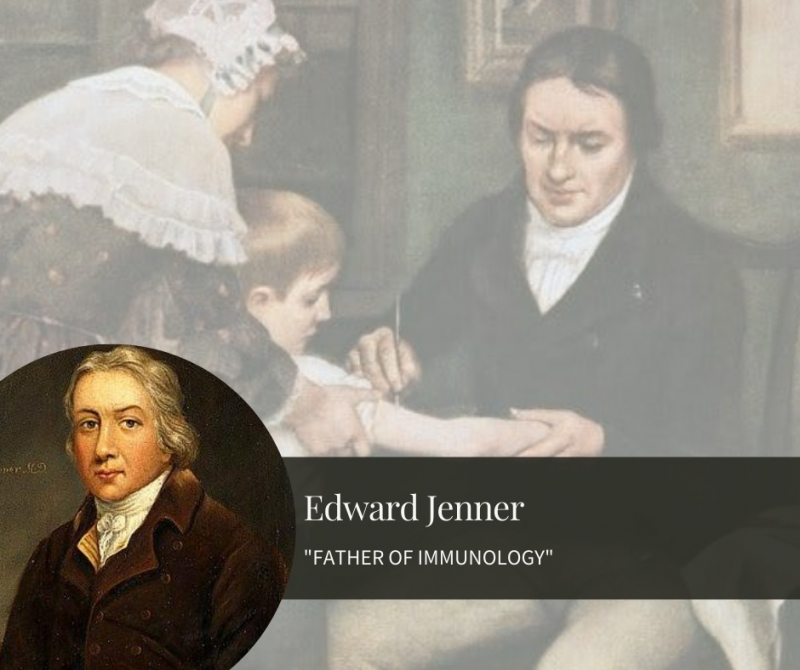

Edward Jenner, a well-known English scientist who is also referred to as the "Father of Immunology", is remembered in medical history. Edward Jenner's work led ... read more...to the creation of the first vaccination in history, which greatly reduced mortality. More lives are reported to have been saved by Jenner's efforts than by any other individual. So, let’s check these ten most interesting facts about Edward Jenner below!

-

First of all, one of the most interesting facts about Edward Jenner is he was orphaned when he was only five years old. The small English town of Berkeley, which is in the county of Gloucestershire, is where Edward Jenner was born on May 17, 1749. He was the seventh of Reverend Stephen Jenner and Sarah's nine children. Stephen, his father, served as Berkeley's vicar. Edward's parents died when he was only five years old, in 1754. The brothers and sisters raised him. Jenner wed Catherine Kingscote in 1788. Edward (1789), Catherine (1794), and Robert were their three children (1797). While Robert and Catherine outlived Jenner, his oldest son Edward passed away in 1810 from TB. Health problems plagued Jenner's wife her entire life, and in 1815 she too passed away from tuberculosis.

Throughout his life, Edward developed a love for the outdoors. The structures of British medical practice and education were changing gradually when Jenner was born. The gap between surgeons and apothecaries, who received their medical training through apprenticeship rather than academic study, and Oxford- or Cambridge-trained doctors, who were far less educated, was gradually closing, and hospital work was taking on a significant amount of importance.

Photo: https://www.journeyinlife.net/

Photo: https://www.britannica.com/ -

Humanity was wiped out by smallpox for many ages. Thanks to Edward Jenner's outstanding work and subsequent advancements resulting from his endeavors, we do not have to worry about it in the present era. One of the most interesting facts about Edward Jenner is that he was variolated as a child. In the 18th century, smallpox was widely distributed and occasionally had unusual intensity outbreaks that had a very high mortality rate. The illness, which was a major cause of death at the time, had little regard for social standing, and those who survived frequently suffered from disfigurement.

Variolation was the standard treatment at the time for smallpox (Variola). Mild smallpox matter was injected into a person to cause variation. Smallpox would then affect the patient less severely than if it had come to him spontaneously. If the symptoms disappeared after a few weeks, the patient recovered and grew immune to the illness. Although usually effective, this approach was not infallible and several people died as a result. Although he had a high fever and had been variolated as a child, Edward Jenner managed to survive. On the other hand, this had a long-lasting impact on his general health.

Photo: https://twitter.com/

Photo: https://www.gloucestershirelive.co.uk/ -

After attending grammar school, he was hired as an apprentice by a neighborhood surgeon when he was 13 years old. He went to grammar school and began working as a surgical apprentice when he was 13 years old. In the eight years that followed, Jenner thoroughly studied the field of medicine and surgery. Jenner started working as an apprentice for nearby surgeon Daniel Ludlow in 1763. During his seven years of training with Ludlow, he gained valuable expertise that helped him later in his profession.

Then he attended St. George's Hospital in London, where he had an anatomy and surgery apprenticeship with John Hunter, one of the most recognized surgeons of the day. What's more, he was a world-class anatomist, biologist, and experimentalist who not only collected biological specimens but also focused on issues related to physiology and function. The two men's strong friendship persisted until Hunter died in 1793. The stimulus that so validated Jenner's innate tendencies - a catholic curiosity in biological phenomena, focused observational skills, honed critical faculties, and reliance on experimental research—could have come from no one else. Hunter gave Jenner the recognizable advice, "Why to think [i.e., speculate] - why not undertake the experiment," to Jenner. From the University of St. Andrews, he received his MD degree. When his studies were over in 1773, Jenner returned to his native Gloucestershire to start a successful career as a surgeon and family doctor.

Photo: John Hunter

Photo: https://commons.wikimedia.org/ -

Jenner returned to country practice in Berkeley in 1773 after spending the previous two years in London studying, where he found great success. He was popular, competent, and capable. He joined two medical organizations in addition to being a physician to advance medical knowledge and occasionally publish medical papers. As a naturalist, I made a lot of observations, especially on bird migration and the cuckoo's breeding behaviors.

Jenner is renowned for penning a study that clarified a particular misconception about the actions of the cuckoo bird. One egg from a cuckoo is laid in the nest of another species of bird. Only the juvenile cuckoo lives as all the eggs and young of the other bird vanish. The foster parents raise it after that unaware that it is not their child. The host's eggs and fledglings are pushed out of the nest by the adult cuckoo, according to popular belief. In a publication, Edward Jenner asserted that the newly hatched cuckoo had wiped out its rivals. A depression on the cuckoo fledgling's back allowed it to cup eggs and other fledglings and push them out, according to Jenner. In 12 days, the depressive episode ends. This wasn't verified until the invention of photography in the 20th century. Jenner was chosen as a Fellow of the Royal Society as a result of these discoveries.

Photo: https://learnodo-newtonic.com/

Photo: https://abcnews.go.com/ -

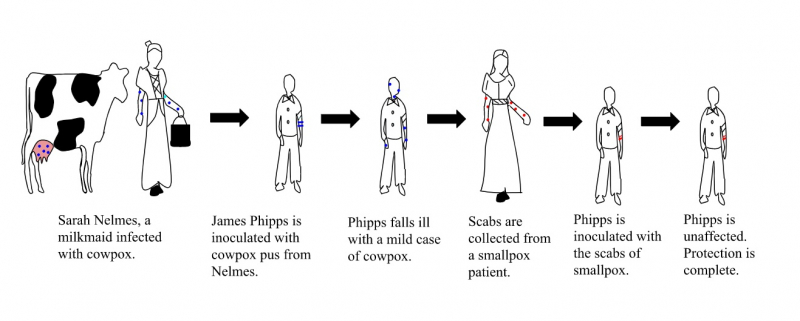

The only defense against smallpox was a crude vaccine technique called variolation, which included purposefully infecting a healthy person with "matter" removed from a patient suffering from a minor case of the illness. Unfortunately, the transmitted illness did not always stay mild, and occasionally there was a fatality. The individual who received the vaccination may also spread the illness to others, serving as a point of infection.

The fact that a person who had experienced an attack of cowpox, a condition that may be caught from cattle, could not take smallpox, i.e., could not become infected whether by accidental or deliberate exposure to smallpox had impressed Jenner. Jenner considered this phenomenon and came to the conclusion that cowpox was an intentional defense system that not only prevented smallpox but also provided protection from it.

The tale of the important discovery is well known. In May 1796, Jenner discovered Sarah Nelmes, a young dairymaid, who had recently had cowpox blisters on her hand. James Phipps, age 8, who had never had smallpox, was vaccinated on May 14 using material from Sarah's lesions. Over the following nine days, Phipps experienced a mild illness, but he was OK by day 10. On July 1, Jenner gave the boy another immunization, this time using smallpox material. No illness spread; full immunity was provided. An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccine was a slim book published privately in 1798 by Jenner after he added more instances.

Photo: https://www.nytimes.com/

Photo: https://dsp.domains.trincoll.edu/ -

The publication did not instantly receive a good response. Jenner traveled to London in search of volunteers for the immunization campaign but was unsuccessful after a three-month visit. Through the efforts of others, particularly the surgeon Henry Cline, to whom Jenner had given some of the inoculants, and the doctors George Pearson and William Woodville, vaccination gained popularity in London. There were challenges, some of which were unpleasant; Pearson attempted to detract from Jenner's accomplishments, and Woodville, a doctor working in a smallpox hospital, infected the cowpox material with the smallpox virus.

Even though Jenner demonstrated that smallpox could be prevented through vaccination, his approach wasn't immediately adopted. First of all, cowpox wasn't common, so doctors had to get Jenner's cowpox material to test the process. Second, because it was managed by physicians who performed variolations or worked in smallpox hospitals, the situation was frequently tainted with the disease. Additionally, the biological mechanisms underlying immunity were not yet fully known; hence, it took a lot of data to be gathered and a lot of trial-and-error to design an efficient technique, even on an empirical foundation. People were also concerned about the negative effects of receiving treatment with animal products. Last but not least, there was religious hostility to immunization due to receiving components from God's lower creation. Despite these obstacles, Jenner's discovery quickly became a hit and spread throughout Europe. Napoleon minted a unique medal as a monument to him in 1804 and the Empress of Russia gave him a ring as a present, among other honors.

Photo: https://www.britannica.com/

Photo: https://www.britannica.com/ -

The death rate from smallpox decreased despite mistakes and sporadic deceit. Despite receiving widespread acclaim and numerous awards, Jenner didn't try to profit personally from his discovery and instead spent a lot of time advancing the cause of vaccination. After retiring from medicine, Jenner continued his research on immunizations. He received various memberships as a result of his work, including those at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1803 he finally was elected president of the Jennerian Society, an organization dedicated to vaccination and the abolition of smallpox. He was chosen to serve as King George IV's chief physician, Berkeley's mayor, and justice of the peace in 1821. He continued his studies in natural history and zoology in between all of these activities.

Jenner was discovered on January 25, 1823, with his right side paralyzed and in an apoplectic state. He died of what seemed to be a stroke the next day. Jenner's vaccination served as the starting point for later immunology breakthroughs. French scientist, roughly 100 years after Jenner's work

Photo: https://www.economist.com/

Photo: https://www.londonremembers.com/ -

Five researchers in England and Germany successfully tested a cowpox vaccine against smallpox more than two decades before Jenner's vaccination. During an epidemic in 1774, Dorset farmer Benjamin Jesty successfully immunized his wife and two children. However, Edward Jenner was the first to openly carry out the experiment and demonstrate that those who had received a cowpox vaccination were immune to smallpox. He also showed that cowpox protective pus may be successfully transmitted from person to person, as opposed to merely directly from cattle. More significantly, it was because of his efforts in the years that followed that the cowpox vaccination was widely used. Jenner is credited with discovering the cowpox vaccine, despite not being the first to test it.

An Act of Parliament outlawed variolation in 1840, and the cowpox vaccination became free and mandatory in 1853. The World Health Organization (WHO) began its global campaign to eliminate smallpox in 1967, and in 1980 it made the official declaration that "Smallpox is Dead!" The most dreaded illness, which had been around since ancient times, had been wiped off, fulfilling Jenner's idea. The work of Edward Jenner "saved more lives than the labor of any other human," according to estimates.

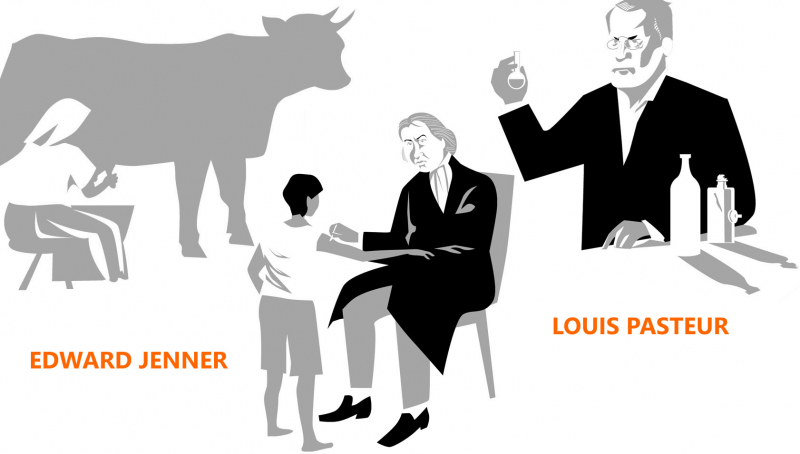

Anti-rabies and anti-anthrax vaccinations were first developed by Louis Pasteur. Edward Jenner is referred to as "the father of immunology" for his groundbreaking work on the subject. In his honor, statues have been built, and many artifacts and locations, like the lunar crater Jenner, have been given his name. Edward Jenner was ranked among the top 100 Britons in a 2002 BBC poll of the entire UK.

Photo: https://multiculturalmuseums.org/

Photo: https://etymology.net/