Top 8 Interesting Facts about Immanuel Kant

One of the most well-known thinkers to emerge from the Age of Enlightenment was Immanuel Kant. His philosophical writings and numerous publications in fields ... read more...like law, history, aesthetics, and astronomy are what he is most famous for. Do you have any knowledge of Immanuel Kant? Let's test your knowledge! 8 interesting facts about Immanuel Kant are selected that most people are unaware of today.

-

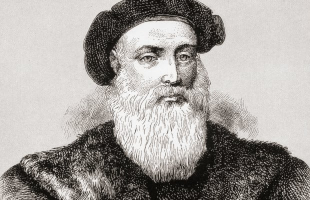

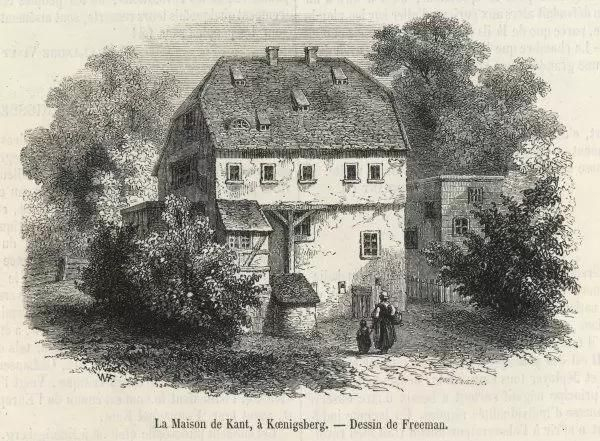

In Königsberg, Kant was born in April 1724. Kant spent his entire life in the isolated province where he was born. Although researchers have not been able to verify Kant's assertion that his father, a saddler, was descended from a Scottish immigrant, his mother was notable for her character and natural brilliance despite having never attended school. The eight siblings of Immanuel. Sadly, most of them did not make it past infancy.

The family frequently struggled with money. However, Kant's parents did not consider money to be significant. They placed a strong emphasis on Latin, religion, and harsh discipline in raising their kids. Both of my parents were devout members of the Pietist branch of the Lutheran church, which preached that morality and simplicity are the expressions of religion. Kant, the fourth of nine children and the eldest to survive, was able to pursue an education thanks to the help of their priest.

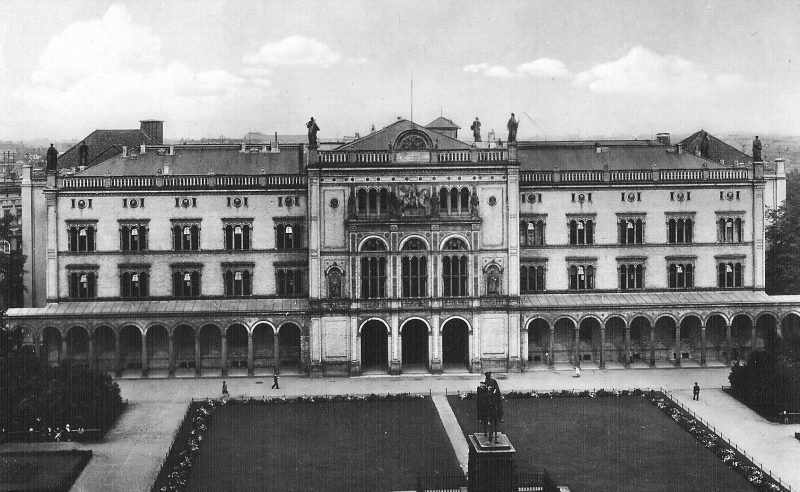

Kant's father passed away when he was enrolled at the University of Königsberg to study mathematics and philosophy. As a result, he had to give up his studies to become a private instructor and support his family. A friend's financial assistance allowed Kant to return to Königsberg over ten years later, where he completed his Ph.D. rather swiftly.

Photo: https://en.wikipedia.org/

Photo: https://www.prints-online.com/ -

One of the most interesting facts about Immanuel Kant is he was a gifted young man with the potential to have a fruitful academic career. Kant enrolled in the Pietist school run by his pastor when he was eight years old. This was a Latin school, and Kant likely developed his enduring love for the Latin classics during his eight and a half years there, particularly for the naturalistic poet Lucretius.

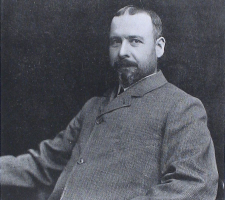

He enrolled as a theological student at the University of Königsberg in 1740. The university was very important to him. Kant began to establish his career while still a student. But despite taking religion classes and even giving a few sermons, his main areas of interest were physics and math. In 1744, Kant began writing his first book, Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces, which addressed a problem involving kinetic forces. Kant was assisted by a young professor who had studied Christian Wolff, a systematizer of rationalist philosophy and a supporter of Sir Isaac Newton's science. Although he had already decided to pursue an academic career at that point, his father's death in 1746 and his inability to secure a position as an undercut or in one of the schools affiliated with the university forced him to leave and look for a way to support himself.

Photo: https://en-academic.com/

Photo: https://commons.wikimedia.org/ -

The circumstances in the family changed following the passing of Kant's father. To make matters worse, Immanuel was unable to secure employment at any of the institutions that were covered by the University. He had no choice but to leave the university and hunt for employment elsewhere.

He obtained work as a family tutor and served three different families throughout his nine-year commitment to the position. He gained social grace, was introduced to the city's powerful society and traveled the furthest from his home city with them—some 60 miles (96 km) to the village of Arnsdorf. He was able to finish his studies at the university and become a Privatdozent, or lecturer, in 1755 thanks to the generosity of a friend.

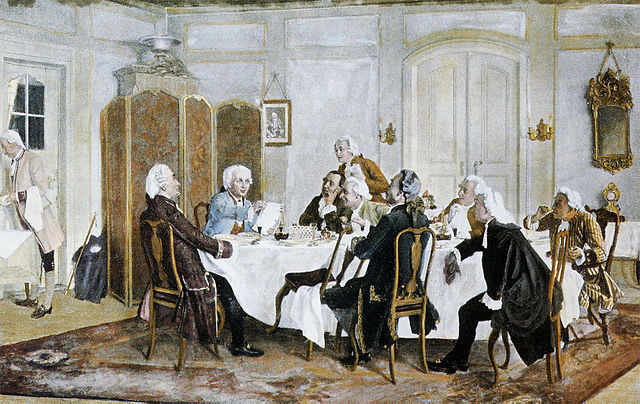

Kant's reputation as a professor and author grew over his 15 years as a Privatdozent. Soon, he was giving lectures on a variety of topics besides physics and math, such as logic, metaphysics, and moral philosophy. He even gave lectures on fortifications and fireworks and ran a well-liked physical geography course for 30 years every summer. He had enormous success as a lecturer, and his lectures, which were very different from his books, were amusing and colorful, infused with numerous examples from his readings in English and French literature, travel and geography, science, and philosophy.

Photo: https://dialektika.org/

Photo: https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/ -

In the 1760s, Kant's criticism of Leibnizianism grew stronger. One of his students claimed that at that time, Kant was criticizing Leibniz, Wolff, and Baumgarten. Baumgarten was a self-declared Newton supporter who also displayed a deep appreciation for the moral theory of Romanticist philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

"An Inquiry into the Distinctness of the Fundamental Principles of Natural Theology and Morals" was his most important piece during this time. He criticized Leibnizian philosophy's assertion that philosophy should be modeled after mathematics and strive to establish a chain of proven facts based on obvious premises in this work. According to Kant, the foundations of mathematics are arbitrary definitions, carefully defined operations, and conceptions that can be demonstrated physically.

Kant stated that philosophy must start with notions that are already established, "albeit confusing or poorly specified," in contrast to this approach since philosophers cannot start with definitions without enclosing themselves within a circle of words. Philosophy must analyze and clarify; unlike mathematics, it cannot advance synthetically. The significance of the moral order, which he had acquired from Rousseau, strengthened his view that a synthetic philosophy is hollow and untrue, which he had also learned by studying Newton.

Photo: https://slidetodoc.com/

Photo: https://www.britannica.com/ -

According to Kant, those who dared to be intelligent helped to create the Enlightenment era. He emphasized the value of having independent thought and not deferring to anyone's authority. Many idealist philosophers of the 19th century were influenced by his writings, and many philosophers of the 20th century were interested in them.

Kant expanded on the notion of moral autonomy as having control over one's behavior. Kant connected the concept of self-government to morality by urging the will to determine its guiding principles rather than allowing our political leaders, pastors, or society to set them for us. Rather than being obedient to an externally imposed law or religious precept, one should be obedient to one's self-imposed law. He referred to the first as heteronomy and the second as autonomy. He outlined enlightenment as "the human being's emergence from his self-incurred minority" in his article "What is Enlightenment," and he urged his readers to have the guts to apply their knowledge "without direction from another" (Kant 1996, 17). Though Kant's account is closely related to what we could recognize as personal autonomy today, it is strongly rooted in his moral philosophy.

Photo: http://churchandstate.org.uk/

Photo: https://www.magicalquote.com/ -

One of the most interesting facts about Immanuel Kant is that he articulated the notion that good can only come from human goodness. Any decent person does deeds of compassion because they freely uphold certain moral principles. According to the legislation, everyone has a responsibility to treat others with respect and as important "human objects." The fundamentals of law indicate that individuals are embodied in one another.

The premise that "goodwill" is the sole thing that is good without qualification serves as the starting point for Kant's critique of conventional concepts. Although the expressions "he's good-hearted," "she's good-natured," and "she means well" are frequently used, "the goodwill" as Kant views it is distinct from any of these common ideas. A "person of goodwill" or, more formally, a "good person" is more similar to the concept of goodwill. Early on in the analysis of ordinary moral reasoning, the term "will" is used in a way that foreshadows later, more technical arguments about the nature of rational agency.

The premise that "goodwill" is the sole thing that is good without qualification serves as the starting point for Kant's critique of conventional concepts. Although the expressions "he's good-hearted," "she's good-natured," and "she means well" are frequently used, "the goodwill" as Kant views it is distinct from any of these common ideas. A "person of goodwill" or, more formally, a "good person" is more similar to the concept of goodwill. Early on in the analysis of ordinary moral reasoning, the term "will" is used in a way that foreshadows later, more technical arguments about the nature of rational agency.

Photo: https://www.amazon.co.uk/

Photo: https://www.philosophytalk.org/ -

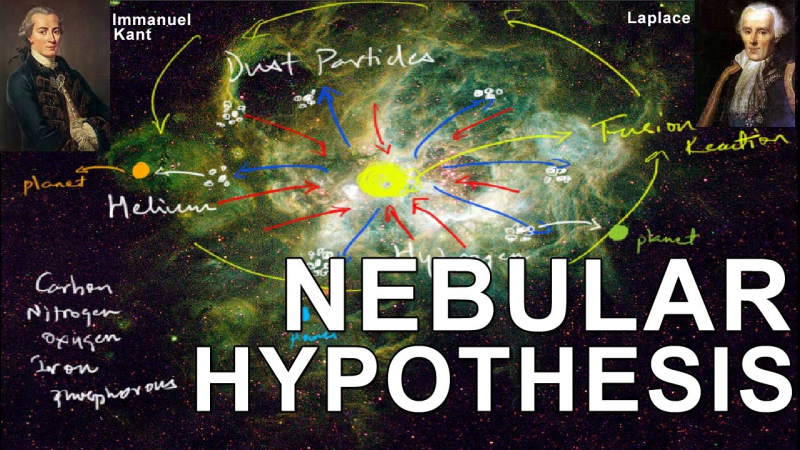

Kant provided an explanation of the development of the Solar System in one of his first publications. Kant postulated a nebular hypothesis of the creation of the solar system in the Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels (1755; Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens), in which the Sun and the planets condensed from a single gaseous cloud. It was then referred to as the Kant-Laplace hypothesis after being independently advanced by Laplace in 1796. At this time, Kant valued the philosophical implications of Newtonian physics just as highly as its scientific merits.

His earliest lessons were in arithmetic and physics, and he never lost interest in advances in science. His publication of multiple scientific books discussing the various human races, the nature of winds, the causes of earthquakes, and the general theory of the skies demonstrates that it was more than just casual curiosity. Immanuel Kant's interest in studying gravity and formulating a solution to the issue of Earth rotation is one of the most interesting facts about Immanuel Kant.

Photo: https://www.cambridge.org/

Photo: https://www.youtube.com/ -

Kant thought that people are unable to access the "thing-in-itself" by overcoming the limitations of the mind. It was one of the ideas that Kant put forth. Why does that matter? The idea holds that individuals only notice an object's look. Humans are unable to comprehend what an object is on its own. After Kant's passing, the concept he offered was frequently explored. "The idea suggests that there are no objects. As a result, we shouldn't consider the nonexistent objects," was the response of some philosophers to Kant's idea.

Unlike what Kant referred to as the phenomenon—the thing as it appears to an observer—the thing-in-itself. Kant argued that although the noumenal contains the elements of the understandable universe, man's speculative reason can only comprehend phenomena and can never enter the noumenon. However, since practical reason, or the ability to act as a moral agent, is impossible without the assumption of a noumenal universe in which freedom, God, and immortality exist, man is not entirely excluded from the noumenal.

Philosophers have debated the relationship between the noumenon and the phenomenon in Kant's philosophy for almost two centuries, and some have determined that his passages on these subjects cannot be reconciled. German Idealists who followed Kant immediately rejected the noumenal as having no existence for the intelligence of man. Insisting that the phenomenal world is an expression of power and that the only place this power can come from is the noumenal world beyond, Kant continued to maintain the absolute reality of the noumenal. He felt that by refuting Idealism, he had avoided this rejection.

Photo: https://www.redbubble.com/

Photo: https://www.youtube.com/