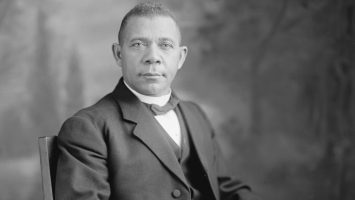

Top 10 Interesting Facts about Leif Erikson

Leif Erikson, whose name has an Icelandic sound to it, was one of the oldest and most well-known Norse explorers of his day. However, despite how old the ... read more...discovery of this Viking explorer may seem, he is regarded as one of the most important historical figures in both other Norse sagas and the United States of America. Below you can find a list comprising 10 interesting facts about Leif Erikson that you should know, ranging from history to popular culture.

-

Leif Erikson's name appears in numerous variants in both medieval chronicles and online sources. Eriksson, Erikson, or Ericson are examples of such variations. However, it is necessary to point out that his last name is a patronymic. Thus, the meaning of his last name, Erikson, is "son of Erik." The last six, which start with a Latin "c," are the furthest from Norse and the least genuine. German is used in the final two, specifically. Keeping in mind that his father, the exiled Erik the Red, was Norwegian, Leif was born an Icelander. Leif's well-deserved claim to fame requires that we settle on a single, reasonable spelling so that everyone may always understand who we are referring to.

Leif typically rhymes with the English word safe (or like "life" depending on the region) and is pronounced "Layf" in Iceland and Scandinavia. However, in America, "Leef" is frequently used instead. You might recall Spongebob Squarepants praising "Leef" Erikson Day in a season two episode if you watched Nicktoons as a child.

Leif's name is also spelled in a variety of ways. The name "Leif Erikson" is spelt "Leifr Eirksson" in Old Norse. However, it is written Leiv Eiriksson in Nynorsk, a more modern form of Norwegian writing. Just the top of the iceberg, really. Some authors use alternative spellings like Ericson, Eriksson, and Erikson, which might further complicate matters. Leif Erikson is the variant that is most frequently used in the United States, so we'll stick with it.

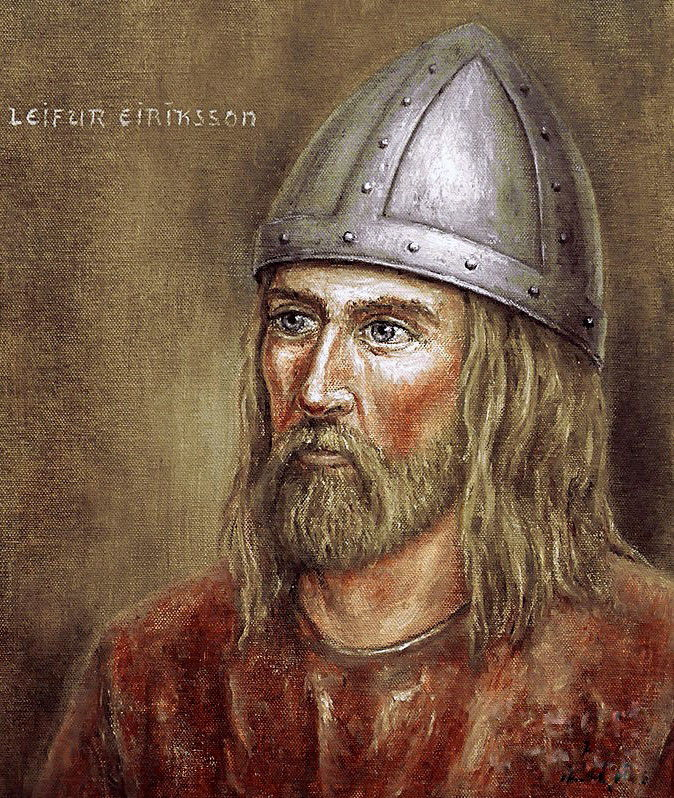

Photo: www.nationalreview.com Video: Words Classes -

A well-traveled Irish abbot named Saint Brendan the Navigator passed sometime in 577 CE. After his passing, legends about his exploits persisted in society, and in the ninth century, a Latin-language biography titled The Voyage of St. Brendan helped to further his reputation.

The book contains certain parts that appear a little unbelievable. The Voyage of St. Brendan claims that Brendan and a small crew launched a wooden sailboat from the Dingle Peninsula. The sailboat was bound in leather. They traveled west in pursuit of the Garden of Eden, and at least according to the book, they found it. Brendan arrived on a lovely island, spent some time there, and then left when an angel instructed him to return to his home. However, there are many who believe the narrative is based on a genuine transatlantic journey Brendan conducted. It has been hypothesized that the paradise Brendan discovered was either a Bahamian Island or North America's eastern seaboard.

Adventurer Tim Severin made the decision to see if the Irish abbot could have accomplished the voyage in 1976. He constructed a 36-foot replica of the kind of ship Brendan would have used using historical documents, and on May 17 he traveled to the Dingle Peninsula with his four-man crew and set sail. On June 26, 1977, after a protracted pit stop in Iceland, they arrived at Newfoundland. This appears to demonstrate that Irishmen in the sixth century had the means to cross the Atlantic, but it doesn't imply that Brendan or any of his contemporaries really did so.

Photo: www.lifeinnorway.net

Photo: allthatsinteresting.com -

An interesting fact about Leif Erikson is, that he was Erik the Red's son, who established the first European settlement in what is now known as Greenland.

Erik the Red, who established the first Norse settlement in Greenland, and Thjodhild of Iceland were the parents of Leif. Although his birthplace is unknown, it is likely that he was born in Iceland, which had just lately been settled by Norsemen, primarily from Norway. He was raised in the Eastern Settlement of Greenland on the family homestead Brattahl. Leif had two known sons: Thorkell, who replaced him as the leader of the Greenland settlement, and Thorgils, who was born to the noblewoman Thorgunna in the Hebrides.

Erik Thorvaldson, also called Erik the Red, was a man with red hair who had a difficult upbringing. Erik was born in Norway, but after his father was found guilty of murder there, the family was exiled to Iceland. There, Erik married a wealthy woman and had four children, one of whom he called Leif. Unfortunately, Erik was briefly banished after killing a neighbor in a battle. Erik chose to travel west instead of back to Norway, settling in a vast, desolate area that had been discovered by another explorer a few years before. In the year 985 CE, Erik's exile was ended, and he made the decision to try to build a new colony on the island he had discovered. Fortunately, he was a PR whiz. He called it Greenland, hoping that others would come and settle there. The plan was successful.

Photo: Teachings in Education -

The Vikings headed south once they were out of Helluland. Their next stop was a region covered in trees that came to be known as Markland, or "the land of wood." According to the sagas, Markland was located north of a third region that the Nordics called Vinland and south of Helluland. Markland is generally believed to have been a section of Canada's Labrador coast. We are aware that Greenlanders continued to go there well into the 1300s, wherever it was. This is due to the fact that a record from 1347 describes a ship that had just made a port call in Markland, albeit no precise information regarding its location is provided.

Vinland's location is a complete mystery. The sagas describe it as a huge region with a valuable resource: grape vines. There were also rumored to be natural grasses, salmon, and game animals. Leif's group established a settlement at Vinland, where they spent the winter before returning to Greenland. The Icelandic sagas recount further Viking incursions into Vinland. The Bishop of Greenland visited there in 1121 CE, according to other texts.

But eventually, the Nordic population stopped visiting Vinland. Even though historians disagree today regarding the location of the site, archaeologists discovered what turned out to be a Viking settlement in Newfoundland in 1960. The location is known as L'Anse aux Meadows, and radiometric dating indicates that it was constructed between 990 and 1030 CE and inhabited for roughly 10 years. That fits perfectly with the sequence of events in the Icelandic Sagas' Leif's account.

Is Vinland's long-lost hamlet located near L'Anse aux Meadows? Maybe. Some analysts argue that it was merely a branch of that fabled colony and would have been used as a rest stop by seafarers. Others speculate that the location could be Markland rather than any region of Vinland.

Photo: u.osu.edu Video: History Profiles -

Leif Erikson's deadly half-sister is one of the interesting facts about Leif Erikson that many people are unaware of. We are given a horrific narrative of Freydis, Erik the Red's daughter, in The Saga of the Greenlanders (who The Saga of Erik the Red tells us was illegitimate). She and her husband Thorvard set sail for the New World with two brothers named Helgi and Finnbogi while Leif served as the chief of Greenland. The couple spent a few months living in Vinland, and it wasn't a fun experience. One day, Freydis asked that Thorvard kill Helgi and Finnbogi after accusing them of beating her (a claim that the saga claims to be false).

Helgi and Finnbogi, along with several other Vikings, were residing at a different campground. The camp, where all the men there had been killed, was visited by Thorvard, Freydis, and several of their neighbors. Freydis, however, was unsatisfied and he seized an ax before slaughtering the camp's unarmed women. Leif learned of this heinous act after she had returned to Greenland, but he was unable to bring himself to punish his half-sibling.

The Saga of Erik the Red oddly never refers to Freydis as a murderer and instead portrays her as a hero for fending off a Native American invasion. Which saga is more accurate is uncertain.

Photo: www.worldhistory.org

Photo: thehistorianshut.com -

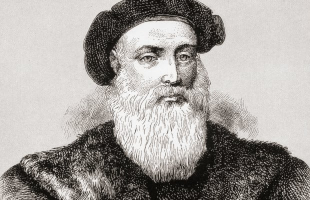

Before Washington Irving produced a spectacularly false biography of the explorer in 1828, Christopher Columbus was not a household name. Despite how misleading the book was, Italian immigrants found the idea of honoring Columbus to be very appealing. President Benjamin Harrison publicly urged his countrymen to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's voyage to the New World in 1892. In 1907, Colorado made Columbus Day an official state holiday at the urging of its Italian citizens. Columbus Day proclamations were first made by presidents in the 1930s, but it wasn't until 1968 that it was officially recognized as a federal holiday.

That interpretation of American history was not shared by everyone. Leif Erikson was traveling across North America 500 years before the Nia, Pinta, and Santa Maria crossed the Atlantic, said Wisconsinite Rasmus Bjorn Anderson in his book America Not Discovered By Columbus, which was published 46 years after Irving's biography of Columbus. On October 9, 1825, a group of Norwegian immigrants arrived in New York City, marking the beginning of organized Scandinavian migration to the United States. Anderson determined that Erik the Red's illustrious son deserved his own celebration to counter Columbus's, and he chose that day as the ideal one. In 1929, Wisconsin became the first state to declare Leif Erikson Day at Anderson's request.

Photo: www.nationalgeographic.com

Photo: time.com -

America Not Discovered By Columbus and similar works helped Leif Erikson gain a devoted following in the United States. But it soon became apparent that some of his supporters didn't just respect him for being a brilliant explorer—they also liked him because he wasn't a Catholic. The rise in immigration from nations like Poland and Italy sparked a backlash against Catholicism in the United States. Honoring Christopher Columbus—an Italian who espoused Catholicism—seemed offensive to many Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Leif Erikson appeared to them to be much more attractive.

Both Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey and congressman John Blatnik presented legislation in 1963 to establish Leif Erikson Day as a national holiday. Congress unanimously approved the observance on September 2, 1964, and asked the President to proclaim it every year. Each president since Lyndon B. Johnson has done so, better source needed], frequently utilizing the proclamation to honor the accomplishments of people of Nordic origin in general and the spirit of exploration. The Canadian Parliament has introduced bills to recognize Leif Erikson Day.

Leif Erikson Day has not yet succeeded in becoming a government holiday, similar to how Columbus Day did. However, a tradition that began in 1964 calls for the current U.S. president to recognize Scandinavian-Americans on October 9 with a proclamation.

Photo: www.nationalgeographic.com

Photo: www.grida.no -

Leif Erikson came from a distinguished line of explorers. He was the grandson of Thorvald Ásvaldsson, who was banished from the Kingdom of Norway during King Haakon Haraldsson's reign and fled to Iceland, and the second son of the reputed Erik the Red, a Norse navigator who discovered Greenland in around 982 (although the Icelandic sagas may suggest Gunnbjörn Ulf-Krakuson as the genuine discoverer of the large Arctic island).

He was also closely related to Naddodd, a Faroese adventurer who accidentally discovered Iceland while traveling between early-medieval Norway and the Faroe Islands after getting blown off course. Thorvald, Erik's older brother, also conducted an expedition to North America, but he was assassinated there by the Native Americans known in the sagas as "Skraelings." His family history is so significant that it is easy to assume that exploration was a tradition in his family.

Photo: www.history.com Video: UsefulCharts -

One of the most interesting facts about Leif Erikson was that he was the first European to discover America. Leif Eriksson and his brave band of Vikings arrived in North America and founded a town 500 years before Christopher Columbus. Some researchers assert that the Americas may have been visited by maritime people from China far earlier, as well as perhaps people from Africa and even Ice Age Europe.

The sagas offer two alternative explanations for how this occurred. According to "The Saga of Erik the Red," a storm forced him to land in North America while his route to Greenland.

However, according to "The Saga of the Greenlanders," Leif Erikson made the journey on purpose after hearing a tale from a trader by the name of Bjarni Herjólfsson. After his ship veered off course to the west of Greenland, Bjarni claimed to have seen a country. Leif collected a crew because he was intrigued by the tale and set off to investigate. At three different locations, they came to a standstill. He placed Helluland, which historians think to be Baffin Island today, in the first place. The second location was what he referred to as Markland, which historians think is Labrador. There were also reports of several woodlands in this area. He referred to the third location as Vinland and said it was full of grapes.

Photo: www.historyextra.com Video: Innovative History -

In Trondheim, Norway; Brattahlid, Greenland; and L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada, Leif has erected replica monuments. There won't be any more reproductions made. For the Trondheim statue, the molds were produced in 1996. Molds do not last forever, therefore Leif considers himself fortunate to have obtained three statues from this series.

Boston built one in 1887 thanks to the efforts of a Harvard chemist who was passionate about Viking mythology. In the following few years, Leif Erikson's sculptures were erected in Milwaukee and Chicago. The 9.5 foot (2.9 m) tall bronze figure, which shows Erikson holding a shield in his left hand, is perched upon a sizable boulder. The words "Leif Erikson Discoverer of America" are engraved on the boulder. Other people rule over Iceland, Newfoundland, and Norway. In Reykjavk, where Leif was born, there used to be a bodyguard for the statue of him that is shown above. The United States gave this sculpture, which weighs a full metric ton, as a present. City officials began to fear that drunk passersby would try to urinate on it after it was put up in 1931. In 1935, night watchmen were posted at Leif's metal feet. Right up until the start of World War II, the statue was still being guarded.

Photo: wikipedia Video: SpiritHighKoala1114