Top 8 Interesting Facts About Marco Polo

Originally from Venice, Marco Polo was a merchant and explorer (Italy). Find out interesting facts about Marco Polo with Toplist.... read more...

-

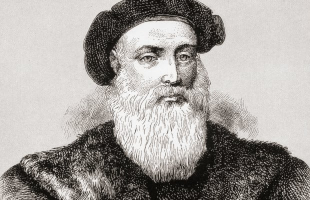

While his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, introduced the European world to the Far East. We all "know" that Marco Polo traveled to China, worked for Ghengis Khan for several years, and then came back to Italy with the ice cream and pasta recipes.

Frances Wood, head of the Chinese Department at the British Library, disagrees, claiming that Marco Polo most likely never even left the Black Sea, where his family was engaged in trade.Marco Polo's journeys from Venice to the exotic and far-off East, as well as the epic book he wrote detailing his remarkable experiences. Why does he not mention such staples of Chinese culture as tea, foot-binding, or even the Great Wall in his romantic and ostensibly in-depth account? Did he bring ice cream and pasta back to Italy? And why is there no mention of Marco Polo in the archives, given China's extensive and even compulsive record-keeping? Did Marco Polo Visit China? is sure to cause a stir.

Another claim claims that Polo wasn't even the first person to travel to China. Niccolo and Maffeo Polo had already traveled to China and met with Kublai Khan before Marco set out on his journey to Asia. Because Niccolo and Maffeo, the two more experienced travelers, had made friends with the great Mongol emperor and informed him about Christianity, the Pope, and the Church in Rome, Marco's journey could be seen as a sort of continuation of their earlier explorations. Kublai Khan asked the travelers to bring him 100 Christian men so he could learn more about the religion and some holy oil of the lamp in Jerusalem because he was curious about European religion. Niccolo and Maffeo left for the East once more after returning to Europe, where they picked up the young Marco Polo and managed to obtain the oil but not the 100 Christians that the emperor had requested.

Photo: KhoaHoc.tv

Photo: www.history.com -

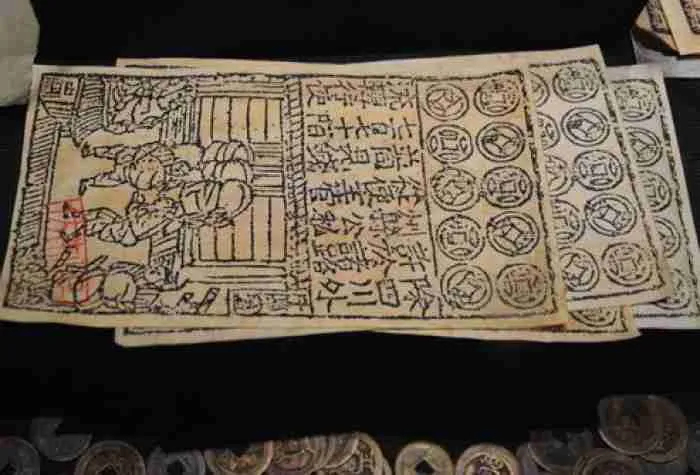

In ancient Chinese texts, the use of paper money is first mentioned. 16 merchants received permission to issue universal bills of exchange during the reign of Emperor Chen Tsung (998–1022). However, the credibility of the currency was damaged when a number of these merchants failed to redeem notes upon presentation, and the general populace refused to accept it. The merchants' rights to issue money were revoked by the Emperor in 1023, and the government's Bureau of Exchange was created with the responsibility of issuing paper money for circulation. These are currently regarded as the very first banknotes printed by the government. Archaeologists discovered printing plates made of brass from this time period, and they have since been used to print replicas of these early banknotes. There are no known examples of this series' original-issue notes remaining.

Marco Polo made a passing allusion to paper being used as currency in the Chinese Empire in his account of his travels through China in 1296. The idea was so absurd and unbelievable to Europeans that they began to doubt the veracity of his accounts of his travels and residence in China.

The oldest original banknote discovered to date was a piece that was found in a cave. Sometime between 1165 and 1174, the Chinese Emperor Hsiao Tsung issued this banknote. This surviving, rather complex example, which is descended from earlier issues of which none have survived, showed the quantity or number of coins it represented on its face.

Photo: Son Of China - Paper Money used for in ancient China

Photo: L'Internaute -

One of the interesting facts about Marco Polo you may not know, Marco Polo's famous travelogue was penned in prison.

Although many people are familiar with Marco Polo, few are aware that The Travels of Marco Polo, his celebrated literary masterpiece, was not only written while he was imprisoned but also by someone else. When Marco Polo's account of his exploits in the Far East was first published, around 1300, it quickly rose to fame and inspired a new generation of explorers, including Christopher Columbus, who kept an annotated copy of it among his personal effects.

The 24-year journey Marco Polo took with his father, Niccol, and uncle, Maffeo Polo, was chronicled in the bestselling biography, autobiography, and travelogue. Marco Polo, who came from a family of intrepid merchants, left Venice at the age of 17 and didn't come back until he was 41. Between 1271 and 1295, he traveled through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir, and China. Even for 17 years, Marco Polo worked at the court of Mongolian emperor Kublai Khan.

At a time when few Christians had ever traveled into the Far East, let alone to China, Marco Polo's travels provided a wealth of useful information for merchants. In fact, according to National Geographic, "the depth of knowledge Marco Polo provided on China and its neighboring lands was unprecedented in its time."

Photo: Amazon.ca - The Travels of Marco Polo, Volume I

Photo: Project Gutenberg - The Travels of Marco Polo, Volume 2 -

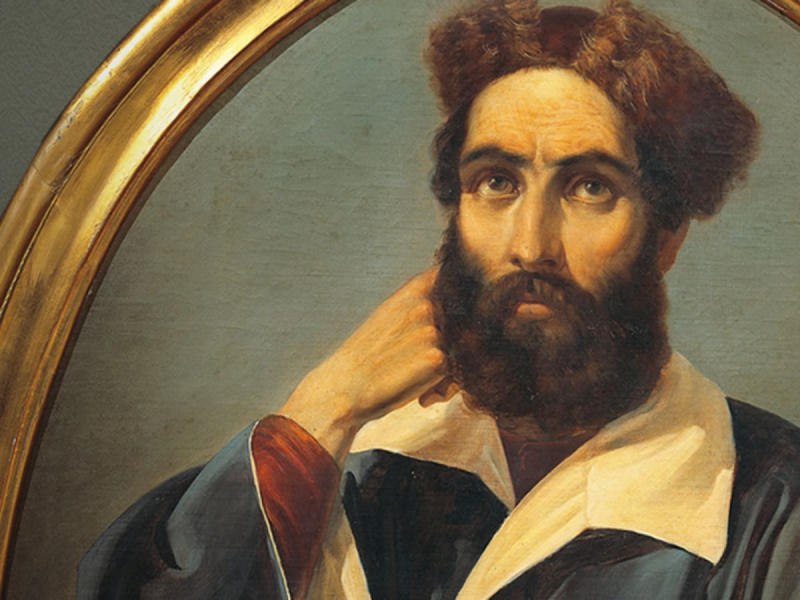

He did the job well, and the Chinese monarch frequently used him as an envoy after that. Some of the places he traveled to had never been explored by Europeans before, and Marco Polo had many strange encounters with Asian tribes that were virtually unknown. He gained promotion after promotion. He served as the mayor of a major Chinese city for a number of years. Marco Polo, his father, and his uncle were all eager to go back to Venice at this point. They had all provided devoted service to Kublai Khan, which he had appreciated and rewarded with wealth, but he did not want to let them go.

The great Khan received the Venetians with great honor, and they soon arrived there. Kublai Khan, who had a special fondness for young Marco, appointed him as his envoy and gave him power. Marco Polo traveled to the Chinese provinces using this authority to complete a variety of tasks, mostly diplomatic ones. Through these journeys, along with his inherent curiosity and extraordinary memory, Marco was able to learn about the customs and way of life of the citizens of this mysterious nation and later to write a unique and descriptive account of his discoveries and impressions. He reportedly traveled by land from Bukhara to China. He mentions his trip to Samarkand in one of his "Book" versions.

He gave the leader insightful reports from the numerous journeys he made throughout Asia on his behalf. This included the three years that he spent overseeing Yangchow as the city's governor.

Photo: The Book Palace! - Marco Polo at the Court of Kubla Khan

Photo: Alamy - Marco Polo and Kublai Khan -

Evidence indicating that Marco Polo had an extramarital child has been discovered by a researcher in Venice. Agnese is thought to have been born sometime between 1295, the year the merchant and explorer arrived back in Venice after spending more than two decades exploring Asia, and 1298, the year he was imprisoned in Genoa for his participation in a naval battle between the two cities.

When Polo was released from prison after serving a year, he returned to Venice and wed Donata Badoer, with whom he had three additional daughters. Polo also wrote a book about his travels that went on to become one of the first bestsellers in history.

There are "hints of Agnese's existence" in other Polo family documents, according to Marcello Bologna, a Ph.D. student at Ca' Foscari University in Venice, but her last will, which was recently found in Venice's state archive, offers convincing proof that the explorer was her father. The document, which was created on July 7, 1319, reveals that Agnese, who passed away in her early 20s, had given her father, Polo, the responsibility of delivering her will to Pietro Pagano at the church of San Felice in the San Giovanni Grisostomo district of Venice. “We know for sure he had three daughters and this document reflects that most probably he had another daughter from a previous relationship,” said Bologna. “We don’t know if he had been married before his second marriage or if the child was born from an affair.”

According to Bologna, the fact that Agnese had given Polo access to her will was evidence that he was aware of her existence and that they had a "strong and trusting relationship." Bolognari claimed that the absence of Agnese's mention of her mother in her will may have indicated that the woman had passed away. He noted that Agnese did a good job of capturing "an intimate and affectionate family life." She had two young children and was married.

Photo: Uncharted Wiki - Fandom

Photo: Adweek -

The Polos offered to go with a Mongol princess who was being sent to Persia to marry Arghun Khan sometime around 1292 (1290 according to Otago). Marco reported that Kublai initially refused to permit them to leave but eventually agreed. In part, because Kublai was approaching 80 and his passing (and the ensuing change in regime) might have been dangerous for a small, isolated group of foreigners, they were eager to leave. Naturally, they also wanted to visit their families and their hometown of Venice.

The princess boarded 14 ships that departed the port of Quanzhou and headed south along with 600 courtiers and sailors, including the Polos. To avoid monsoon storms, the fleet made brief stops at Champa, several islands, and the Malay Peninsula before settling for five months on the island of Sumatra. The North Star appeared to have descended below the horizon, which greatly impressed Polo. Following this, the fleet followed the west coast of India and the southernmost parts of Persia before passing close to the Nicobar Islands, touching down once more in Sri Lanka or Ceylon, and finally anchoring at Hormuz. Once in Khorsn, the expedition handed the princess off to Maḥmūd Ghāzān instead of Arghun, who had passed away.

The Polos eventually traveled to Europe, but it is currently unknown where they went; it's possible that they remained in Tabriz for a while. Unfortunately, they were robbed of the majority of their laboriously acquired wealth as soon as they left the Mongol dominions and entered Trebizond in what is now Turkey. They eventually arrived in Venice and Constantinople after additional delays (1295). One well-known piece of Polo lore is the tale of their dramatic rediscovery by family members and neighbors who had assumed they had long since passed away. Polo reportedly never left Venetian territory for the last two decades of his life.

Photo: Google Sites

Photo: campingcanyelles.com -

In the Republic of Venice's archives, Marco Polo is most frequently referred to as Marco Paulo de confined Sancti Iohannis Grisostomi, or Marco Polo of the Contrada of St. John Chrysostom Church.

But throughout his life, he also went by the nickname Milione, which is Italian for "Million." His book was titled Il Libro di Marco Polo detto il Milione, which translates to "The Book of Marco Polo, dubbed "Milione"" in Italian. The 15th-century humanist Giovanni Battista Ramusio claimed that when he returned to Venice, his fellow citizens gave him the moniker because he insisted that Kublai Khan's wealth was measured in millions. He was referred to as Messer Marco Milioni in more detail (Mr. Marco Millions).

Luigi Foscolo Benedetto, a 19th-century philologist, was persuaded that Milione was a shortened version of Emilione and that this nickname was used to distinguish Niccol's and Marco's branch of the Polo family from other Polo families because both Niccol and his father were known by the nickname.

Photo: Grunge

Photo: tellioglu.com.tr -

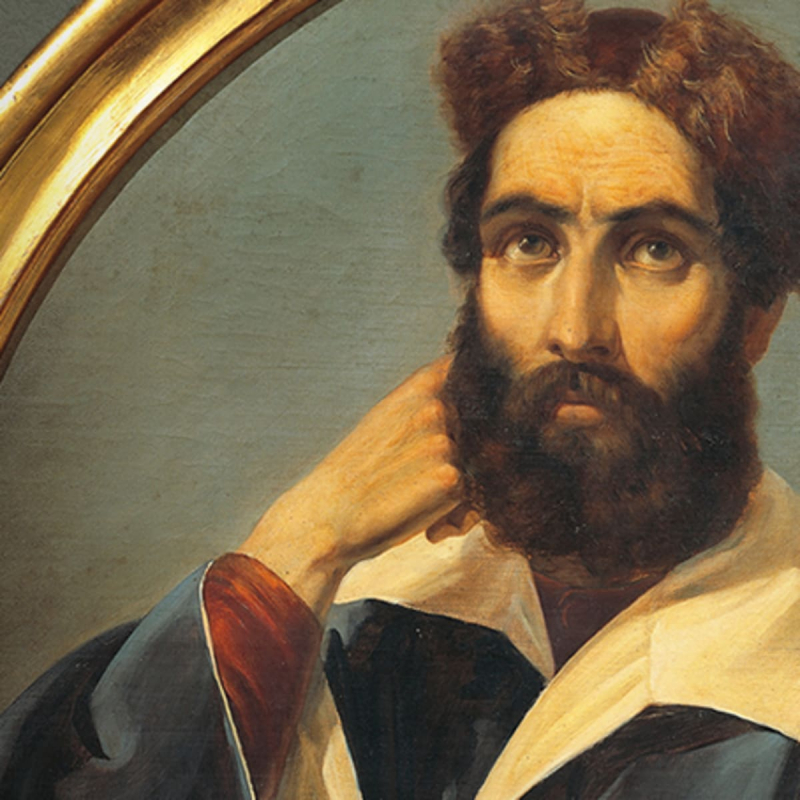

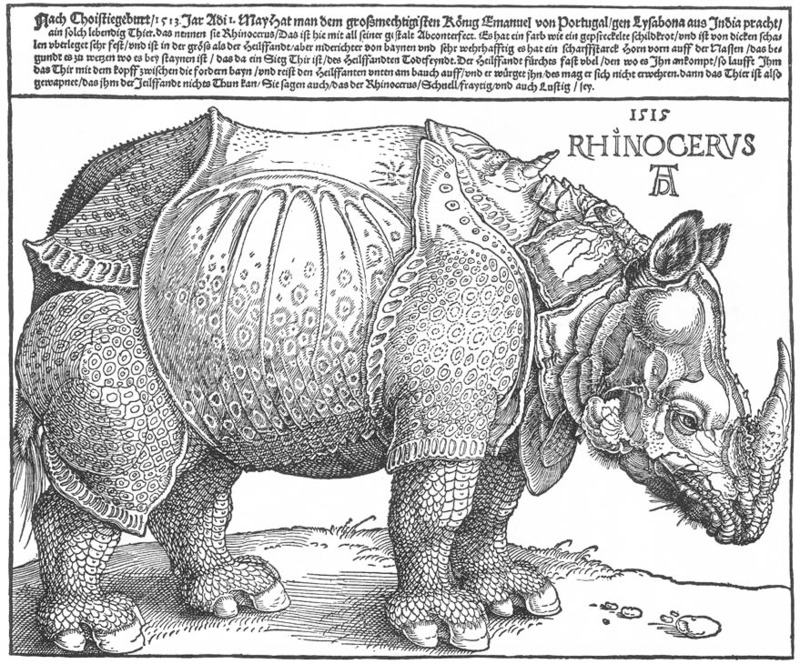

One of the fun facts about Marco Polo, he thought rhinoceroses were unicorns.

Marco Polo announced to the world that he had discovered unicorns during his travels through the islands of Sumatra in the 13th century. There were "numerous unicorns," he wrote, "very nearly as big" as the "wild elephants" he had also discovered in the same habitat. He had not only found one. They were not the majestic horses he had anticipated; instead, they were said to be so pure that, according to legend, they would only lay their heads on the lap of a virgin maiden. They did, in fact, resemble a species that one might anticipate to find on the island he called Java the Less: the rhinoceros. Polo told his readers that unicorns mostly enjoyed rolling around in the mud and dirt and biting people with their sharp tongues. Historians now understand that Polo was actually describing the rhinoceros when he described the "unicorn" in his writing.

However, Marco Polo was unaware of rhinoceroses. He knew unicorns existed, so any animal that moved on four legs and had a horn on its nose had to be a unicorn, even if it was a rather unimpressive example of the species. The Asian two-horned rhino was the rhinoceros he was most likely to encounter in Sumatra, so the fact that the rhinos he came across most likely had two rather than one horn on their noses did not sway his opinion. It had to be a unicorn if it had four legs and a horn on its nose.

Photo: Quora - Marco Polo describe unicorns

Photo: Cycle Croatia