Top 8 Interesting Facts about Marie Curie

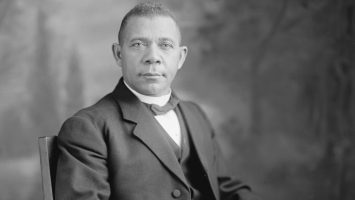

Born Maria Salomea Sklodowska on November 7, 1867, in Poland, Marie Curie grew up to become one of the most noteworthy scientists of all time. Her long list of ... read more...accolades is proof of her far-reaching influence, but not every stride she made in the fields of chemistry, physics, and medicine was recognized with an award. Here are some interesting facts about Marie Curie you might not know.

-

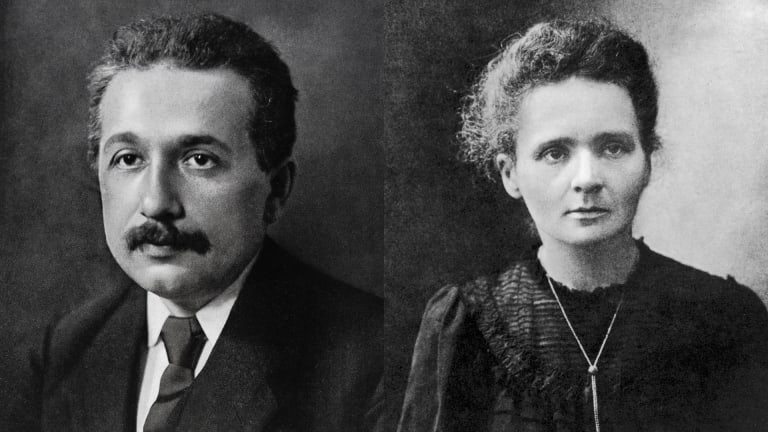

In 1906, a horrific automobile accident claimed the life of Pierre. By 1911 Marie Curie had dedicated a lot of time to work but was barely receiving the credit she deserved. She went to the Solvay Conference in Brussels, which brings together the top physicists in the world. Curie was the sole female participant.

She had her first encounter with Albert Einstein in this location. At the time, misogyny, xenophobia, and antisemitism were at their height in France. Curie fell into profound despair as a result of being shut out of any settings in which she could outperform any male competitors. Around this time, Einstein took it upon himself to write Curie a thoughtful letter in which he expressed his admiration and inspiration for her passion and brilliance. He pleaded with her to persevere, to battle on, and to know that there were those who supported her.

Fans of Albert Einstein eagerly anticipated a time in December 2014 when the Digital Einstein Papers initiative made a wealth of his correspondence, diaries, and postcards online accessible. The roughly 5,000 documents provided some insights into his thought process, but the letter to pioneering female physicist Marie Curie that provided some Einsteinian advice on how to handle the public's appetite for information about her private affairs struck many.

Photo: https://www.biography.com/news/albert-einstein-letter-to-marie-curie

Photo: https://www.reddit.com/r/interestingasfuck/comments/qsy6mr/albert_einstein_and_marie_curie_discussing_near_a/ -

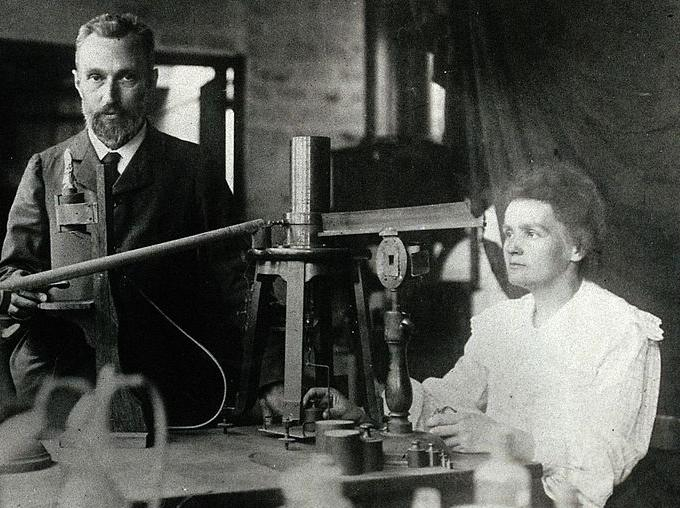

Following graduation, Marie Curie was hired to perform research and joined forces with Pierre Curie, a friend of a coworker, to find lab space. Additionally, he taught at the Sorbonne. Two years later, the Curies got married. Pierre and Marie initially worked on separate projects at the beginning of their relationship, but following the birth of their first child, Pierre started working with Marie on x-ray and uranium studies.

When Curie asserted that uranium rays were dependent on their atomic structure rather than their physical shape, she was researching uranium rays. Marie Curie herself developed the term "radioactivity" at the time, defining it as the ray activity that depends on the atomic structure, or the number of atoms, of uranium. Her idea gave rise to a new branch of research, atomic physics. Marie and Pierre worked with pitchblende for a while. Uranium oxide crystallizes into the mineral pitchblende, which contains roughly 70% uranium.

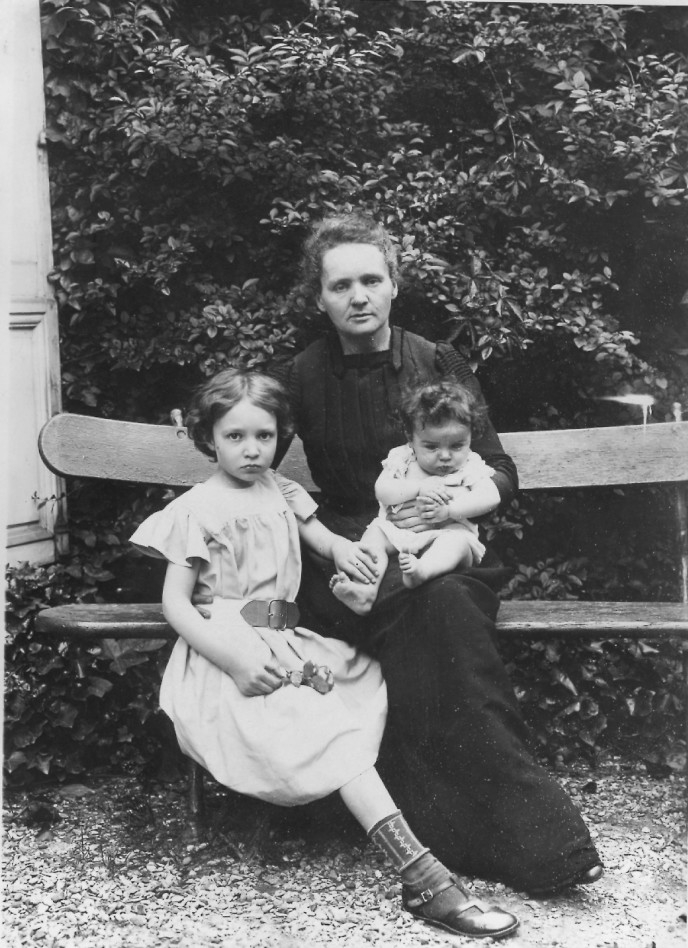

With the use of pitchblende, Marie and Pierre discovered radium in addition to polonium. For their research on radioactivity, Marie Curie and her husband received the Nobel Prize in physics in 1903. She was the first female recipient of the Nobel Prize. The Nobel Prize winner Pierre died in an accident three years later. Marie Curie took over Pierre's teaching duties at the Sorbonne even though she was a widow, a single mother of two, and a widower. Curie received her second Nobel Peace Prize in Chemistry in 1911.

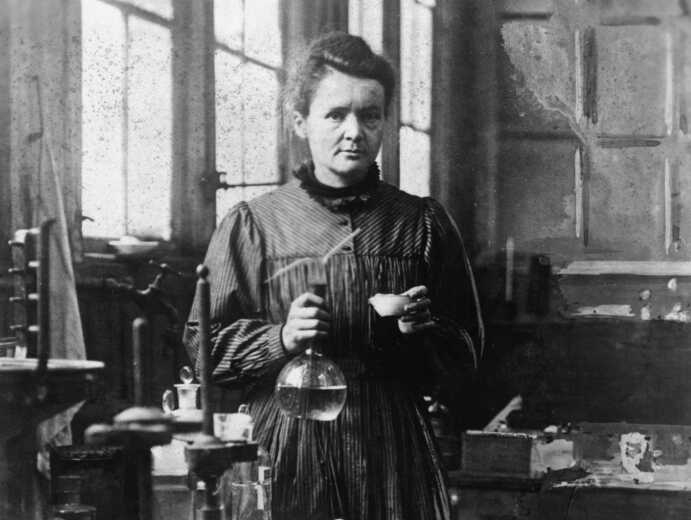

Photo: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Curie

Photo: https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/what-did-marie-sklodowska-curie-ever-do-us -

The cabinet made the decision to relocate to Bordeaux as the German army advanced on Paris. The one gram of radium in Curie's lab was all of France's research supply. Marie Curie, accompanied by government employees, boarded a train headed for Bordeaux at the government's request while transporting the priceless element in a large lead box. Curie, however, believed she belonged in Paris, unlike many others. She took a military train back to Paris after depositing the radium in a Bordeaux safe-deposit box.

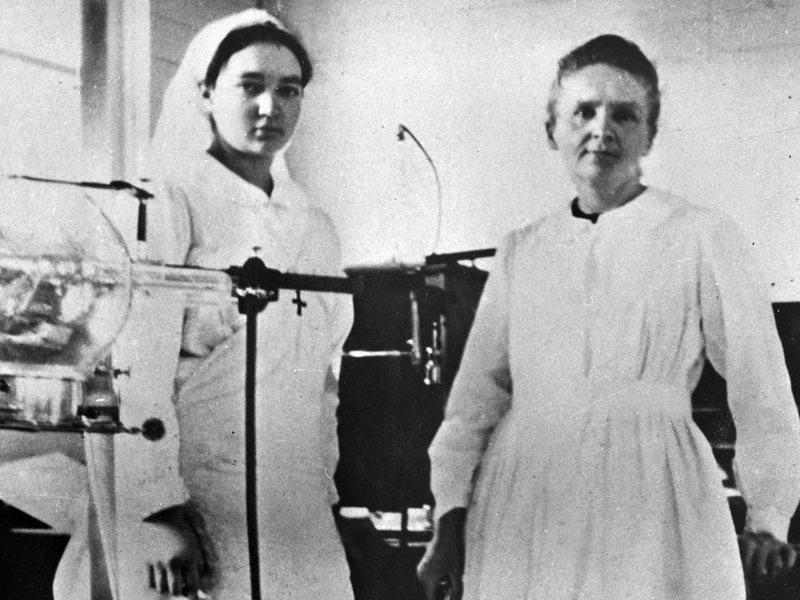

She understood that X-rays could save soldiers' lives by enabling medical professionals to spot bullets, shrapnel, and damaged bones. She persuaded the government to give her the authority to establish the first military radiology facilities in France. As the Red Cross Radiology Service's newly appointed director, she extorted cash and luxury vehicles from her rich friends.

She persuaded auto body shops to convert automobiles into vans and pleaded with equipment manufacturers to contribute to their nation. The first of her 20 radiological trucks was ready by the end of October 1914. These mobile radiography units, which took X-ray equipment to the injured at the front lines of battle, came to be known by the French enlisted troops as petites Curies (little Curies).

Photo: https://spectrum.ieee.org/how-marie-curie-helped-save-a-million-soldiers-during-world-war-i

Photo: https://www.argunners.com/marie-curie-world-war-one/ -

One of the interesting facts about Marie Curie is that the Nobel Prize Committee initially ignored Marie Curie. Few people were aware of the Nobel Prize at the time; it had been founded in 1895. The wealth left behind in Alfred Nobel's bequest, a Swedish dynamite creator, was used to support the awards for chemistry, literature, peace, physics, and physiology or medicine. They were to be given out in honor of achievements in academia, science, or culture. The first Nobel Prize was given out in 1901 after Nobel's passing, but the Curies are credited with making the honor well-known.

Simply because Marie was a woman, she nearly didn't get the honor. Marie, Pierre, and Henri Becquerel were all nominated for the Nobel Prize in physics in 1902 by a member of the committee called Charles Bouchard, a physician, but they were not selected for the award that year. Then in 1903, without mentioning Marie, four additional distinguished men on the committee proposed Pierre and Henri for their work with radioactive elements.

Three of these four experts were sufficiently familiar with the Curies' research to be certain that Marie was the one who had independently isolated radium and discovered radioactivity in pitchblende. They nonetheless asserted that Pierre and Henri Becquerel "worked together and separately to secure, with much difficulty, some decigrams of this priceless mineral."

Photo: https://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2010/12/14/132031977/don-t-come-to-stockholm-madame-curie-s-nobel-scandal

Photo: https://www.biography.com/news/marie-curie-biography-facts -

In the sciences of chemistry and physics, Marie Curie was a titan. The first person to receive two Nobel Prizes was her. She is also one of just two individuals to ever receive the Nobel Prize in two distinct fields. Following Henri Becquerel's discovery of a novel phenomenon in 1896 that she subsequently named "radioactivity," Marie made the decision to determine whether the characteristic found in uranium might also be present in other materials. She and Gerhard Carl Schmidt both found out that this was accurate for thorium. Her interest was piqued by pitchblende when she turned her focus to minerals.

The only explanation for pitchblende, a mineral with activity higher than pure uranium, is that very small amounts of an unidentified material with extremely high activity were present in the ore. The effort Marie had begun to address this issue was soon joined by Pierre, and as a result, polonium and radium were discovered. Pierre devoted most of his time to researching the new radiations' physical properties. Marie achieved the complete barium-free isolation of one-tenth of a gram of radium chloride in 1902. The significance of this work was quickly acknowledged by scientists.

Marie, Pierre, and Becquerel each received a share of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903. The Nobel Prize was awarded to Marie for the first time in any field. It wasn't until Marie and chemist André-Louis Debierne, one of Pierre's students, extracted pure radium alone in 1910. Pure radium was found to have radioactivity that was more than a million times greater than either uranium or thorium. For isolating pure radium, Marie received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911.

Photo: https://www.sciencehistory.org/historical-profile/marie-sklodowska-curie

Photo: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/336292297160044191/ -

Marie Curie's laboratory couldn't accommodate her growing radioactive studies because of space constraints. According to Goldsmith, the Austrian government pounced on the chance to hire Curie and offered to build her a state-of-the-art laboratory. To have a laboratory for studying radiation built, Curie bargained with the Pasteur Institute. The Radium Institute, also known as the Institut du Radium, at the Pasteur Institute, which is now the Curie Institute, was nearly finished by July 1914. Curie put her research on hold when World War I started in 1914 and set up a fleet of portable X-ray units for use by doctors at the front.

She put a lot of effort into fund-raising for her Radium Institute after the war. But by 1920, she was already experiencing health problems, most likely as a result of her contact with radioactive substances. Aplastic anemia, which occurs when the bone marrow fails to create new blood cells, caused Curie's death on July 4, 1934. According to historian Craig Nelson's book "The Age of Radiance: The Epic Rise and Dramatic Fall of the Atomic Era," Curie's physician stated that her "bone marrow could not react possibly because it had been harmed by a protracted accumulation of radiations."

Photo: https://snippetsofparis.com/marie-curie-sklodowska/

Photo: https://www.history.com/news/marie-curie-facts -

Irène Curie, who was married to Frédéric Joliot in 1926, was the daughter of Pierre and Marie Curie and was born in Paris on September 12, 1897. She began her academic career at the Paris Faculty of Science and worked as a nurse radiographer throughout the duration of World War One. She completed a thesis on the alpha rays of polonium, for which she was awarded a Doctor of Science in 1925. She performed significant research on natural and artificial radioactivity, the transmutation of elements, and nuclear physics either independently or in partnership with her husband; for this work, which is outlined in their joint paper, Production artificielle d'éléments radioactive, they shared the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Her study of how neutrons interact with heavy atoms in 1938 had a key role in the discovery of uranium fission. She was hired as a lecturer in 1932, rose to the position of professor at the Paris Faculty of Science in 1937, and then was named director of the Radium Institute in 1946. Irène participated in the organization's founding and the building of the first French atomic pile during her six years as a commissioner for atomic energy.

She worked on the plans for the major nuclear physics center at Orsay, and she was apprehensive about its opening. This facility had a 160 MeV synchro-cyclotron, and F. Joliot carried on building it after she passed away. She was active in the World Peace Council and the Comité National de l'Union des Femmes Français, and she had a strong interest in the social and intellectual growth of women. Irene Joliot-Curie was chosen to serve as the Undersecretary of State for Scientific Research in 1936. She held honorary doctorates from multiple universities and belonged to a number of international academies and scientific organizations. She was also an officer in the Legion of Honour. 1956 saw her passing in Paris.

Photo: https://www.nobelprize.org/womenwhochangedscience/stories/irene-joliot-curie

Photo: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ir%C3%A8ne_Joliot-Curie -

Although Marie Curie's early professional life was exclusively spent in Europe, she eventually visited the United States—in fact, twice. She made her first trip to the White House in 1921 to receive a gram of radium for her research that had been crowdfunded by American women. She met President Warren G. Harding at that time, who gave her the radium and introduced her to his wife, Florence Harding, who helped with the fundraising.

She met President Herbert Hoover when she came back in 1929 to get supplies for her work. On this visit, there was "considerably less pomp," according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology. To begin with, unlike in 1921, she was given money to purchase radium ($50,000, enough for one gram) as opposed to the actual radium. The Great Depression was made possible by the stock market meltdown that occurred two days after Curie arrived. However, according to NIST, President Hoover took the time to welcome her to the White House and give her the bank draft.

Curie sent Hoover a thank-you message following her visit. In her letter, she said, "I believe that it was extremely nice of you and Mrs. Hoover to devote time and concern to me in these particularly anxious days.

Photo: https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/marie-curie-marie-meloney-and-the-significance-of-a-gram-of-radium

Photo: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/marie-curie-with-the-us-president-w-g-harding-washington-d-c-may-20th1921-coll-acjc-source-mus%C3%A9e-curie-coll-acjc/RQGr8TLM3iAgTA