Top 5 Interesting Facts about Maximilian I

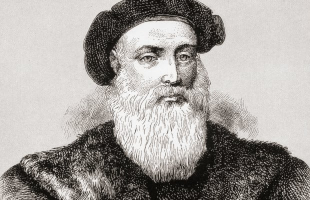

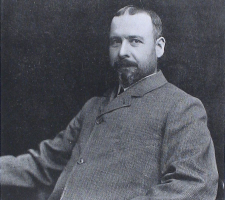

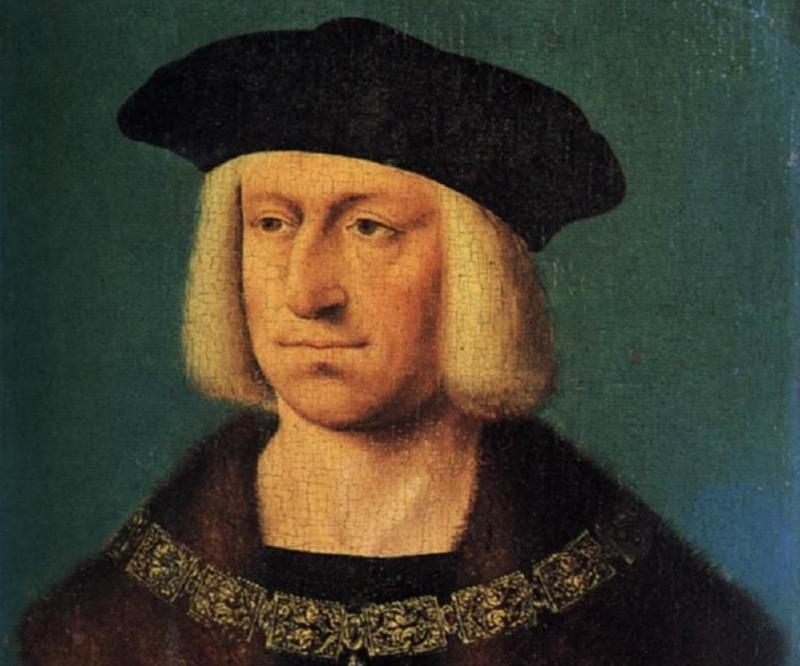

Maximilian I (March 22, 1459 - January 12, 1519) was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death, but he was never anointed by the Pope. He reigned as ... read more...King of the Romans (also known as King of the Germans) from 1486. Here are the five interesting facts about Maximilian I.

-

One of the interesting facts about Maximilian I is that he had a traumatized childhood. Maximilian I saw the fierce rivalries that occasionally resulted in armed confrontation within the dynasty. His uncle Albrecht VI's siege of the Vienna Hofburg in 1462, along with his aristocratic allies and irate people, was one early and likely traumatizing event during his boyhood. Three-year-old Maximilian was stranded inside the palace with his parents as it was being heavily cannonaded. The residents of the palace started to hunger, and little Maximilian, who had already been debilitated by an unknown sickness, became seriously ill. The character contrasts between his parents, whose traits were completely at odds with one another, caused Maximilian additional suffering.

His mother Eleonora was a vivacious woman who occasionally showed her outright hate of her phlegmatic husband, while his father, Emperor Frederick III, was a harsh and secretive man with profoundly pragmatic beliefs. His parents held opposing views regarding politics and upbringing. While Eleonora spoiled her son and created the groundwork for his distinct sense of monarchical duty and love of the outward display that signified his position and standing, his father wanted him to acquire a practical education and to be hardened toward bodily suffering. Maximilian was torn like a child between his parents. A lower jaw deformity that resulted in an incredibly pronounced lower lip also caused Maximilian to have a speech impairment as a toddler.

Eleanor of Portugal -Photo: en.wikipedia.org

Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor -Photo: en.wikipedia.org -

Although Maximilian was married three times, only the first marriage resulted in children. Mary of Burgundy (1457-1482) was Maximilian's first spouse. The marriage was annulled by Mary's passing in a riding accident in 1482 after they were wed in Ghent on August 19, 1477. His true passion in life was Mary. Even at his advanced age, the simple mention of her name made him cry (although, his sexual life, contrary to his chivalric ideals, was unchaste).

Theuerdank, in particular, in which the hero saved the damsel in peril as if he had preserved her inheritance in real life, was one of the big literary projects that Maximilian commissioned and completed in significant part many years after she passed away. His wish is that her mausoleum in Bruges contains his heart. In addition to her beauty, her inheritance, and the fame she brought, Mary fit Maximilian's ideal of a woman: a vivacious magnificent "Dame" who could coexist with him as sovereign. He gave this description of Mary to their daughter Margaret: "From her eyes shined the force (Kraft) that exceeded any other lady."

The contract between Anne of Brittany (1477-1514) and Maximilian was dissolved by the pope in early 1492, but by that time Anne had already been coerced by the French king Charles VIII (who was engaged to Margaret of Austria) to repudiate the contract and marry him instead. Anne and Maximilian were married by proxy in Rennes on December 18, 1490. In 1493, Maximilian married Bianca Maria Sforza (1472-1510), who brought him a substantial dowry and enabled him to exercise his authority as Milan's imperial overlord. They had no children, and the marriage was unpleasant.

Mary of Burgundy -Photo: en.wikipedia.org

Bianca Maria Sforza - Photo: en.wikipedia.org -

One of the interesting facts about Maximilian I is that Maximilian was often disturbed by his financial situation. Maximilian's ambitious plans were often impeded by money problems. Huge resources were consumed by several battles, the upkeep of a gorgeous court, and the finance of his ambitious goal of political expansion. He was frequently on the point of financial collapse despite the massive income from the Tyrolean silver mines. He occasionally found himself in unpleasant circumstances as a result of this, such as when he was forced to depart Innsbruck and left his second wife Bianca Maria Sforza and her entourage as security for his creditors. Maximilian bequeathed his heirs a mound of debt that future Habsburg generations would find difficult to repay.

The House of Habsburg grew reliant on its bankers for its financial support. The amount of debt owed by the Habsburgs towards the conclusion of Maximilian's reign ranged from six million to six and a half million gulden, depending on the source. The outstanding debt was predicted to be worth 400,000 guldens by 1531. (about 282,669 Spanish ducats). He had spent about 25 million guldens over his whole reign, a large portion of which came from his most devoted people, the Tyrolers. The most that can be said about his financial methods, according to historian Thomas Brady, is that he borrowed fairly from both rich and poor people and defaulted on his debts in an equally fair manner. Comparatively, Charles V left Philip a debt of 36 million ducats when he abdicated in 1556 (equal to the income from Spanish America for his entire reign).

Photo: thefamouspeople.com

Photo: prints-online.com -

It is a fact that Austria was rid of the Jews under Maximilian I. Under Maximilian, Jewish policy was quite erratic, frequently affected by economic factors and the emperor's wavering attitude toward alternative viewpoints. Maximilian ordered the expulsion of all Jews from Styria and Wiener Neustadt in 1496. He permitted thirteen Jewish expulsions between 1494 and 1510 in exchange for significant financial compensations from the local government (the evicted Jews were permitted to relocate to Lower Austria). This contradiction, according to Buttaroni, revealed that even Maximilian himself did not think his expulsion decision was fair. But after 1510, it only happened once, and when a campaign to drive Jews out of Regensburg was launched, he displayed an exceptionally firm stance.

According to David Price, for the first seventeen years of his rule, he posed a serious threat to Jews; but, from 1510, even if his attitude remained exploitative, his policies began to alter. Maximilian's success in extending imperial taxation over German Jewry was likely a contributing factor in the change; at this point, he probably thought about the possibility of raising tax revenue from enduring Jewish communities rather than short-term financial compensation from local governments attempting to drive Jews out. Maximilian granted the anti-Jewish agitator Johannes Pfefferkorn permission to seize all offensive Jewish literature (including prayer books), with the exception of the Bible, in 1509 by relying on the influence of Kunigunde, his devout sister, and the Cologne Dominicans. In Frankfurt, Bingen, Mainz, and other German cities, the confiscations took place.

Frankfurt -Photo: coinsweekly.com

Photo: alchetron.com -

One of the interesting facts about Maximilian I is that Maximilian I employed media policy for political purposes. Maximilian was an extremely well-liked king during his own reign thanks to his commanding public presence and his skillfully executed "media policy." He meticulously worked on his "Memoria", which was intended to record his history for future generations, in an effort to glorify himself and his reign. Maximilian was a skilled user of the contemporary media available to him at the time, such as printing, and he used the pamphlet, the precursor to the modern newspaper, to his advantage in order to control the flow of information. King Charles VIII of France was the target of the emperor's attacks in these media as well as on the battlefield. His extensive genealogical and heraldic program was one of Maximilian's public relations priorities.

He used the contemporary media of the day to spread this, commissioning books that were simple to reproduce and giving his claims to domination a tangible shape. He released his Triumphzug (Triumphal Procession), an intricate set of printed woodcuts illuminating a fictitious event, drawing on the old Roman tradition of the imperial triumph. A masterwork of early printing is the Ehrenpforte (Gate of Honour), which is fashioned after a classical arch of victory. Albrecht Dürer and Albrecht Altdorfer also contributed, although Jörg Kölderer, a talented artist at Maximilian's court, was mostly responsible for its creation. It was a large-format, colorful, and gilded painting that was delivered to various European courts as a declaration of Maximilian's monarchical claims.

Photo: en.wikipedia.org

Photo: wikidata.org