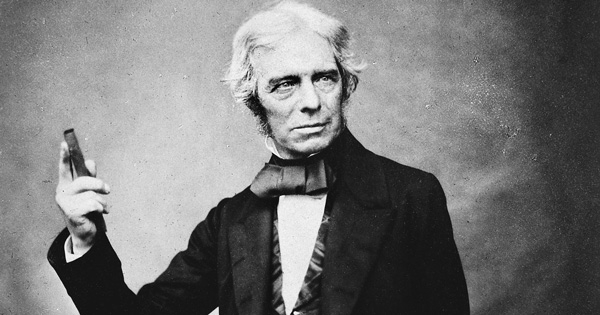

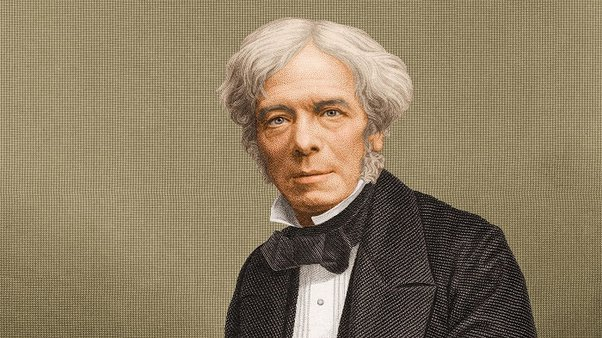

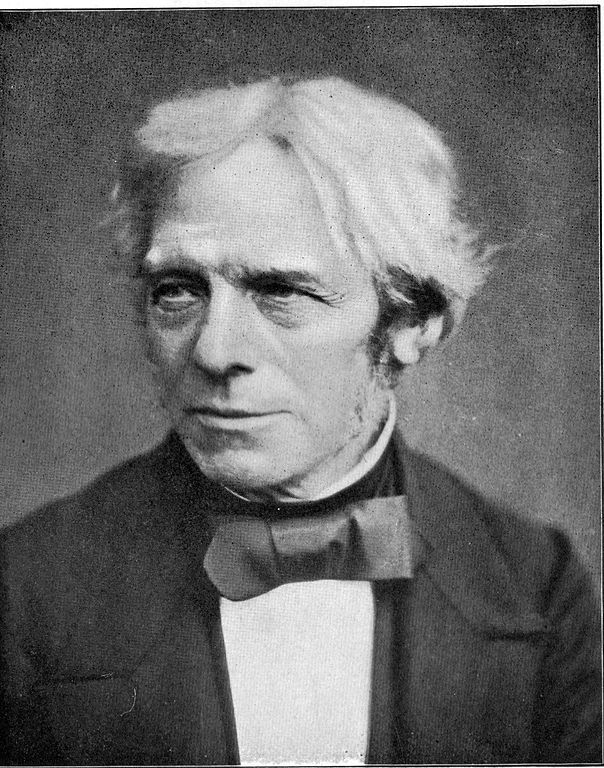

Top 10 Interesting Facts About Michael Faraday

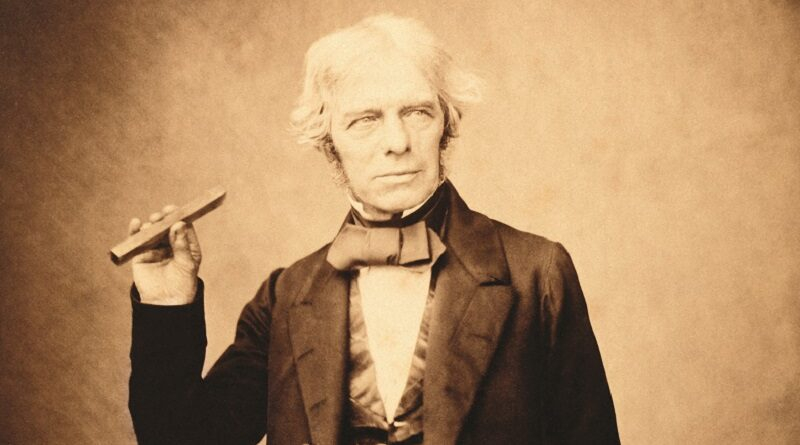

On September 22, 1791, physicist Michael Faraday was born into poverty. Faraday was a self-taught English scientist who excelled in chemistry and physics and ... read more...went on to become one of history's most significant thinkers. He is well known for his contributions to the subject of electromagnetic and is known as the "Father of Electrical Engineering". Do you have any curiosity about this great scientist? If yes, today let's follow Toplist to discover 10 interesting facts about Michael Faraday.

-

Faraday (1791–1867) was a self-educated English scientist who specialized in electromagnetic and electrochemistry. His father James was a sickly blacksmith who struggled to support his wife and four children in one of London’s poorer outskirts. As a result, at the age of 13, Faraday was obliged to work to help his family make ends meet.

George Ribeau, a bookseller, offered him a free apprenticeship. Faraday spent the next seven years mastering the art of bookbinding. Faraday stayed at Ribeau's store after hours, reading many of the same books he'd bound together. Faraday's official education was restricted, as it was for other lower-class youths. However, he learned himself chemistry, physics, and a mysterious force known as "electricity" in the space between those bookcases. He never went to college and had no formal education beyond basic reading, writing, and math.

When Faraday's apprenticeship ended, a Riebau customer offered him tickets to four lectures by Humphry Davy, the Royal Institution's professor of chemistry. He went to the meeting and took copious notes. Faraday applied for a job at Davy and submitted his notes in his application. Davy was so impressed that he employed Faraday as his assistant for the next 18 months while Davy toured scientific institutes across Europe.

Humphry Davy aided Faraday's scientific education by introducing him to well-known European scientists such as André-Marie Ampère (after whom the ampere or amp is called) and Alessandro Volta (for whom the volt is named). Faraday took over as professor of chemistry at the Royal Institution after Davy retired in 1827. With the achievements that he has done, surely this is one of the interesting facts about Michael Faraday that surprised many people.

Photo: pitara

Photo: themarginalian -

Faraday was a great experimenter who communicated his thoughts in plain and easy language; unfortunately, his mathematical talents were restricted to the simplest algebra and did not extend beyond trigonometry. He is described as "mathematically ignorant" by almost all of his biographers. He never studied mathematics, and his contributions to the field of electricity were solely experimental.

So, why is he included in a mathematicians' archive? Faraday's work, after all, is what led to the development of sophisticated mathematical theories of electricity and magnetism. For example, in 1846, he proposed that light is an electromagnetic phenomenon, but his hypothesis was discarded since he couldn't prove it mathematically. In 1864, scientist James Clerk Maxwell developed equations that helped to establish Faraday's idea. Maxwell remarked that Faraday's use of lines of force demonstrates that he was "in truth a mathematician of a very high order, one from whom future mathematicians may learn valuable and productive methods." The farad is the SI unit of capacitance named after him.

Photo: quora

Photo: newsd -

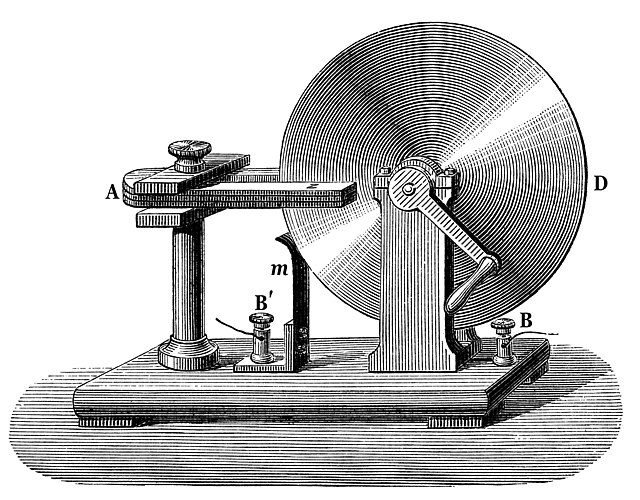

Other scientists had demonstrated by 1820 that an electric current generates a magnetic field, and that two electrified wires exert a force on one another. Faraday believed that these forces could be harnessed in a mechanical device. He began experimenting at the Royal Institute in 1822. In the bottom of a mercury-filled glass jar, he placed a magnet. A cable dangling overhead was connected to a battery by Faraday. The wire began rotating around the magnet after an electric current was supplied through it. To put it another way, that was the very first electric motor. "Very satisfactory," Faraday wrote in his journal, "but make more sensible apparatus".

Faraday found that moving a wire through a stationary magnetic field can induce an electrical current in the wire a decade after his discovery with the motor, the idea of electromagnetic induction. Faraday demonstrated this by creating a mechanism in which a copper disc spun between the two poles of a horseshoe magnet and generated its own power. The Faraday disc, as it was afterwards known, was the world's first electric generator.

Photo: commons.wikimedia.org

Photo: twitter -

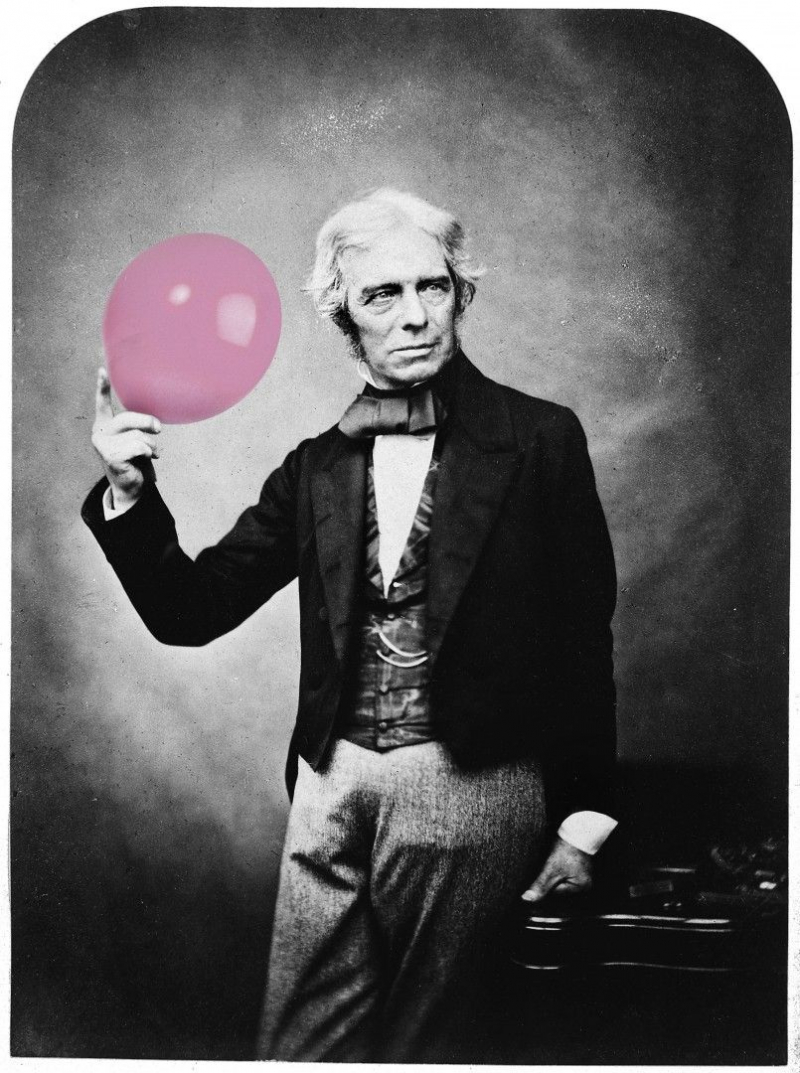

A balloon is a thin, flexible bag that may be filled with air and inflated. Rubber latex is commonly used. Professor Michael Faraday created the first rubber balloons in 1824 for use in his hydrogen experiments at the Royal Institution in London. In the same year, he reported in the Quarterly Journal of Science, "The caoutchouc is highly elastic." "Bags manufactured of it...have been inflated by forcing air into them until the caoutchouc became extremely transparent, and when expanded by hydrogen, they became so light that they formed balloons with great ascending power..." Faraday made his balloons by cutting a circle out of two sheets of rubber that had been put together and pressed together. To prevent the opposite surfaces from fusing together, the tacky rubber bonded automatically, and the inside of the balloon was wiped with flour.

His early balloon models are shoddy by today's balloon standards. They were invented by Faraday, who praised the bag's "great rising power." The following year, toy companies began distributing them. Thomas Hancock, a pioneer rubber producer, introduced latex rubber toy balloons as a do-it-yourself kit that included a bottle of rubber solution and a condensing syringe. J.G. Ingram of London invented vulcanized toy balloons in 1847, which, unlike earlier types, were unaffected by temperature changes. They are considered the prototype of current toy balloons.

Photo: pinterest

Photo: thehomegrownprofessor -

Sir Humphry Davy had a significant impact on science. He found five new elements in the year 1808 alone, including calcium and boron. Davy's lectures at the Royal Institution drew large numbers on a regular basis.

Faraday, then twenty years old, attended four of these demonstrations in 1812 after receiving tickets from a customer. Faraday scribbled meticulous notes as Davy talked, which he later collated and bound into a small book. Davy received Faraday's 300-page transcript. The seasoned scientist was so impressed that he employed him as a lab assistant. Davy was asked later in life to name the most important discovery he'd ever made. "Michael Faraday", Davy replied.

Regardless, tensions would arise between mentor and protégé. As Faraday's achievements surpassed his own, Davy accused the younger man of plagiarizing another scientist's work (a story that was later debunked) and attempted to prevent his membership to the Royal Society.

Photo: sciencehistory

Photo: doisongvietnam -

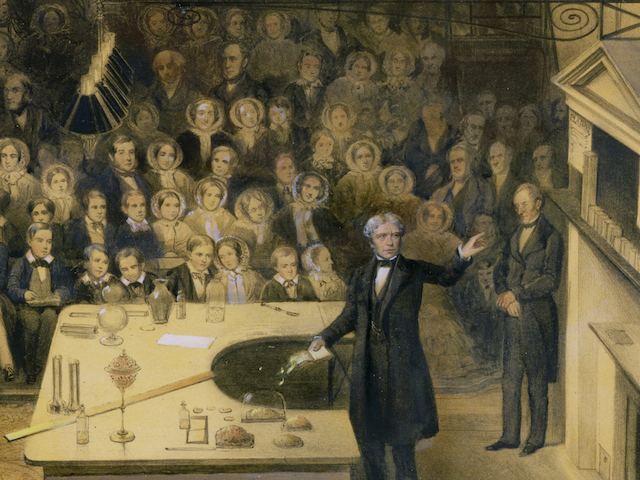

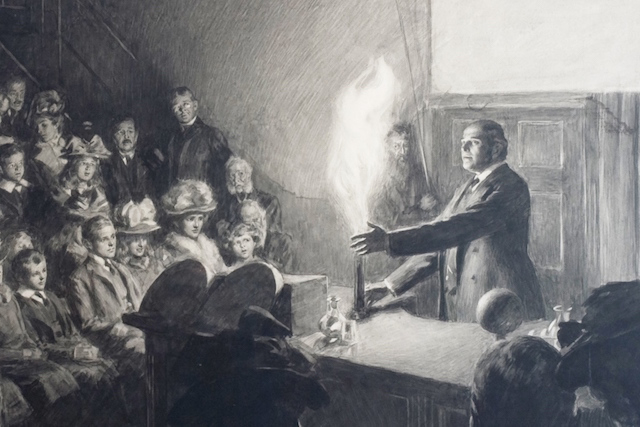

The Christmas lectures are the world's most popular science talks for children and adults, and they have inspired both children and adults. Faraday recognized the value of making science accessible to the general audience. Since 1825, when organized education for children was uncommon, Michael Faraday's Christmas lectures have pioneered an exciting new manner of imparting science to youngsters.

The Lectures have been held annually since 1825, except for World War II. Nobel Laureates William and Lawrence Bragg, Sir David Attenborough, Carl Sagan, and Dame Nancy Rothwell are among those who have delivered the Lectures. On 19 occasions, Faraday was the speaker.

The Christmas lectures are the earliest science television series, having been aired in 1936. Since 1966, they have been televised every year on the BBC, and then on Channel Five, Channel Four, and other channels4. The Lectures were reintroduced to BBC Four in 2010.

Photo: londonist

Photo: londonist -

The £20 note is a sterling banknote issued by the Bank of England. The Bank of England now issues banknotes in the second-highest denomination. The current polymer note, which was originally released on February 20, 2020, features Queen Elizabeth II on the obverse and painter J. On the back, M. W. Turner is depicted. It took the place of the cotton paper note with a likeness of economist Adam Smith, which had been in circulation since 2007.

On June 5, 1991, the Bank of England presented a £20 note containing Faraday's picture to commemorate his contribution to British science. He joined an illustrious company of Britons, including William Shakespeare, Florence Nightingale, and Isaac Newton, who all had their own notes. The bank estimates that 120 million Faraday notes were in circulation by the time it was withdrawn in February 2001 (a total of more than 2 billion pounds). The banknotes have a lilac color and until now you will probably still find these notes circulating in the UK. This is indeed a wonderful British tribute to the world's great scientist.

Photo: numista

Photo: numista -

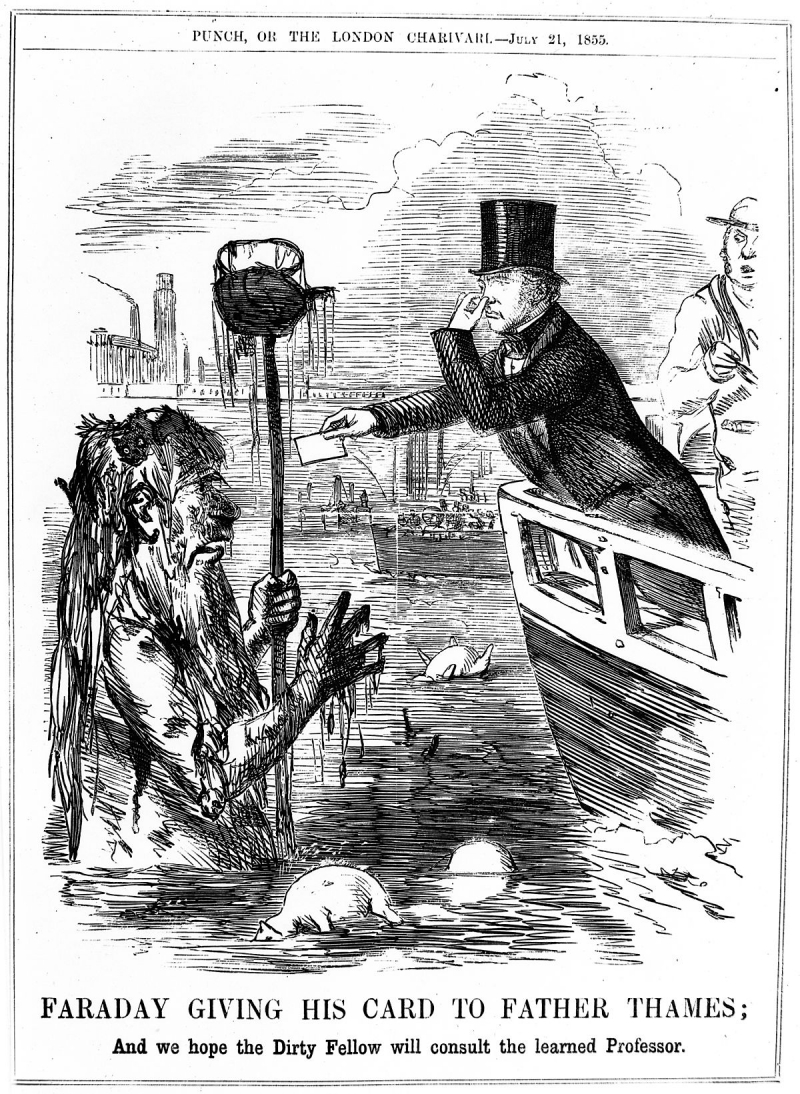

Garbage and feces were often tossed into the River Thames as London got more populated in the nineteenth century. You can imagine how bad it smelled. Faraday was also involved in environmental science, or engineering, as it is now known. He looked into industrial pollution in Swansea and was briefed by the Royal Mint about air pollution. Seeing the unpleasant consequences to come in the near future, Faraday sent an open letter about the matter in 1855, pleading with the government to act. "We cannot hope to do so with impunity if we disregard this issue," he wrote, "and we ought not to be surprised if, before many years have passed, a hot season gives us painful proof of the foolishness of our indifference".

A scorching summer drove Londoners to hold their noses, just as Faraday prophesied. The Thames' rotten stink wafted all throughout the city during the summer of 1858, dubbed "the Great Stink." A comprehensive sewage reform measure was introduced in Parliament in response. Thus, besides being a talented scientist, one of the interesting facts about Michael Faraday is that he also has very positive contributions to society.

Photo: commons.wikimedia.org

Photo: londonnewsonline -

Faraday experienced a sickness in 1839, when he was 48 and still in the throes of his genius, that kept him from working for more than three years. He never fully recovered from this illness, and for the rest of his life, he complained of poor memory and periodic bouts of giddiness and confusion. He lived to be 75 years old. Faraday experienced a sudden bout of vertigo and shakiness in his walk. Despite the fact that he continued his studies and made more significant discoveries (such as diamagnetism), he retreated from social life and did not keep up with the scientific breakthroughs of his day.

Faraday continued to experience unexplained bursts of euphoria, despair, and severe forgetfulness. “[My] bad memory,” he wrote, “both loses recent things and sometimes suggests old ones as new.”. Nobody knows what caused the illness, while some speculate that it was caused by his exposure to mercury. This is one of the interesting facts about Michael Faraday, because with a genius mind and his dedication to science, no one would have thought that he would have memory problems for such a long period of time.

Photo: discoverwalks

Photo: twitter -

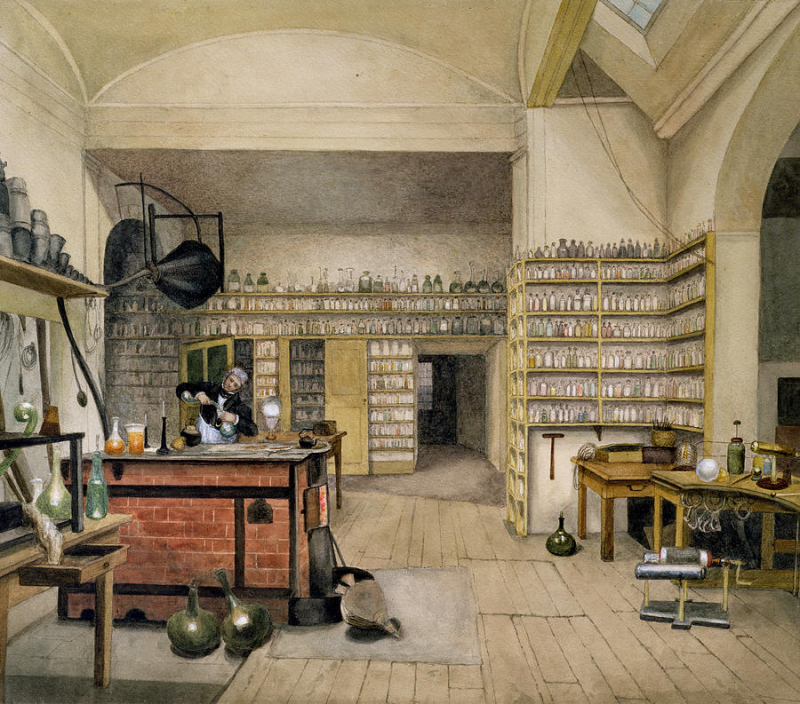

At the Royal Institution, an organization dedicated to promoting applied research, Faraday held a number of scientific positions. Faraday was eventually selected as its Fullerian Professor of Chemistry, a permanent position that allowed him to conduct study and experiments at his leisure. The Faraday Museum at the Royal Institution has precisely recreated his magnetic laboratory from the 1850s. Michael Faraday's fundamental discoveries of the magneto-optical effect and diamagnetism were made in this laboratory.

The area was a servants' hall before the Ri moved in, as evidenced by the old dumbwaiter that Faraday later used to store his experiments (behind the door in this photo). It was utilized as an apparatus storage by 1819, and Faraday secretly took it over for his own studies in the 1820s. The chamber is located beneath the main part of the structure and has limited natural light, making it ideal for experiments involving light beams.

The laboratory became a storehouse after Faraday's death in 1867, and it was left undisturbed. The centenary of his discovery of electromagnetic induction was commemorated in 1931 with a large display at the Albert Hall, which included a full-scale recreation of the lab. The original room's history was ultimately recognized, and it has since functioned as the heart of the Royal Institution's museum. The contemporary design of the room is based on a painting by Faraday's acquaintance Harriet Moore from the 1850s. Except the oil lamp, all the things on display were used by Faraday and include some of his most important inventions and apparatus, including the electric motor, homo polar generator, and the huge electromagnet he employed in his diamagnetic studies.

Photo: atlasobscura

Photo; pixels