Top 8 Interesting Facts About Oliver Cromwell

One of the most polarizing figures in British history, Oliver Cromwell is still regarded by some as a champion of democracy and a radical revolutionary, while ... read more...others portray him as a killjoy Puritan who oversaw the king's execution. Here are interesting facts about Oliver Cromwell.

-

Cromwell was born into the landed gentry into a family that was descended from Thomas Cromwell's minister's sister (his great-great-granduncle). On his father's side, the Cromwell family had a long history of wealth. Although he came from a wealthy family in Huntingdonshire, he belonged to a junior branch, and despite being a gentleman, he was not wealthy. They belonged to the group of people who owned a lot of land in the area. Since they benefited from Thomas' administration of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, his family amassed enormous wealth. Cromwell had a good life, but not one like the upper-class families. His education was also respectable.

Only four of his letters and a summary of a speech he gave in 1628 remain, so little is known about the first 40 years of his life. Oliver had to leave Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge when his father passed away in 1617 in order to care for the estate, his mother who had recently lost her husband, his wife Elizabeth, and ultimately their nine children. Financially, it was a struggle, but Oliver's luck changed after his uncle gave him leases on several properties in Ely, including the lease on the home he and his family moved into in 1636 and lived in for just over ten years. The obligation to collect the local taxes was included in the lease.

Photo: History and Biography

Photo: The Guardian -

Cromwell, who was raised in a middle-class family and was born in 1599, converted to Puritanism in the 1630s. He was chosen to serve as a Member of Parliament in 1640, and from 1642 to 1651, he fought alongside the Roundheads in opposition to King Charles I's Royalist (Cavalier) forces.

He participated in the formation of the New Model Army, a military force of well-equipped and highly trained soldiers that gave promotions to deserving individuals regardless of social standing. It didn't take Cromwell long to show that he was a capable leader, and he was crucial in the downfall of the Royalists.

Without a doubt, he is among the most contentious, divisive, and controversial historical figures, this is one of the interesting facts about Oliver Cromwell. Oliver Cromwell is regarded by some as the "father of democracy," a savior, and a hero who fought for liberty, while he is despised by others as a villain, a ruthless leader, a religious bigot, and nothing more than a murderous hypocrite.

Cromwell's reputation has undergone numerous revisions over the centuries since his death in 1658 at the age of 59 as historians have worked to assess and dissect one of history's most complex characters.

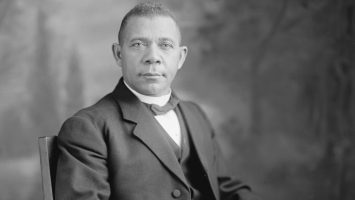

Photo: BBC

Photo: Art UK -

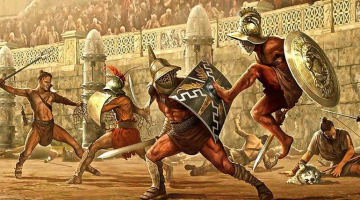

Cromwell was tasked with organizing the defense of Norfolk when the English Civil War broke out in 1642. Because of his courage and organizational prowess, Cromwell was given command of the cavalry when the East Anglian counties established the Eastern Association. His cavalry's significant contribution to the Battle of Marston Moor furthered his reputation. Cromwell was appointed General of the Horse when the New Model Army was established, and he was crucial to the King's defeat at the Battle of Naseby.

Cromwell contributed to the effort to maintain Parliament's cohesion after the Civil War, which was won by Parliament. In 1647, when the army mutinied and refused to disband, he also made an effort to resolve the conflict between Parliament and the army. He was significant in the Second Civil War.

Here are some of Oliver Cromwell's most significant reforms:

- He was the driving force behind both the Commonwealth's founding and the decision to put the King to death in 1649.

- Cromwell left for Ireland to put an end to the Irish Civil War after he had stabilized England. He was a fervent Puritan and had never forgave the Catholics for allegedly killing Protestants in 1641.

- As a result, he believed it was okay to exact revenge and was in charge of the Drogheda Massacre in September 1649.

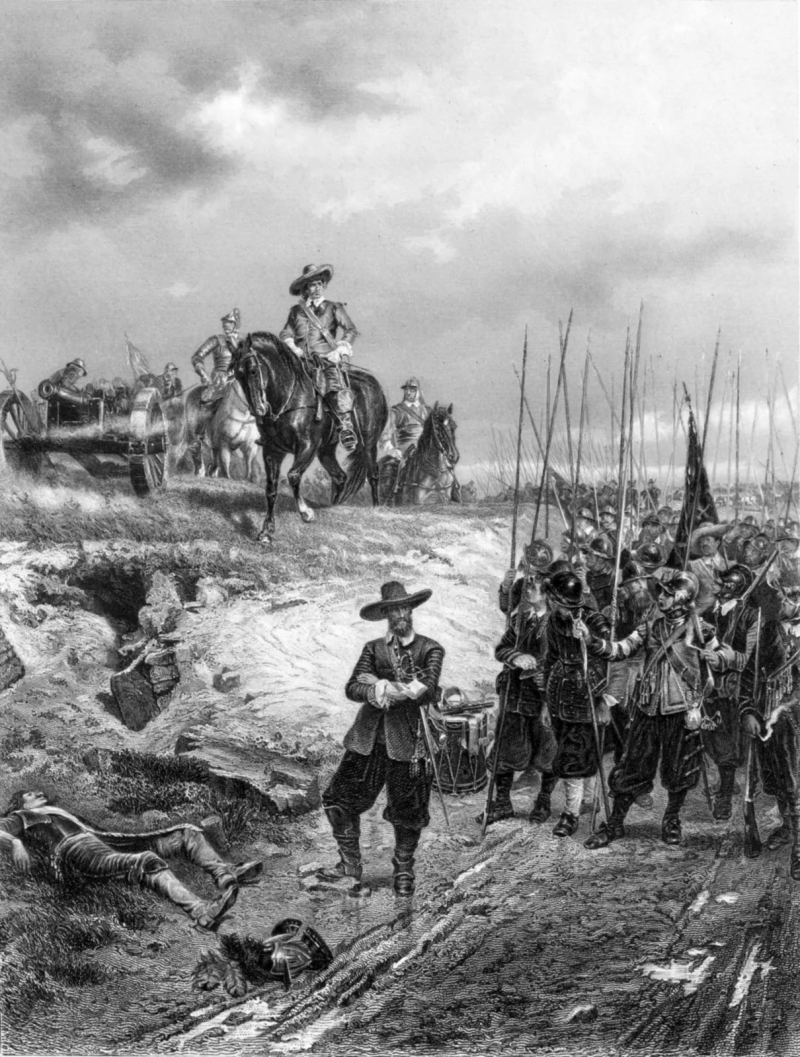

Photo: History on the Net - English Civil War: (1642–1651

Photo: Britain Magazine - Oliver Cromwell and the English Civil War -

You may not know, that one of the interesting facts about Oliver Cromwell, Cromwell built a reputation as a military planner and a fighter during the year 1643. He made it a point to find obedient and well-behaved men regardless of their social standing or religious beliefs. He had insisted from the beginning that the men who served on the parliamentarian side should be carefully chosen and properly trained. After being promoted to colonel in February, he started recruiting for a superior cavalry regiment. He enforced strict discipline while demanding that his troopers be treated well and paid on time. They were fined for swearing, put in the stocks for being intoxicated, called each other "Roundheads"—a derogatory term the Royalists used to refer to them because of their close-cropped hair—and whipped for deserting. He trained his cavalrymen so well that he could check and reform them after they were charged in combat. One of Cromwell's outstanding qualities as a combatant commander was that.

He served in the eastern counties that he was so familiar with throughout 1643. These formed a well-known center of parliamentary strength, but Cromwell was unwilling to remain on the defensive and made the decision to launch a counterattack to stop the infiltration of Yorkshire Royalists into the eastern counties. On July 28, in Lincolnshire, he won the Battle of Gainsborough by rallying his troops in the face of an unconquerable foe. The Isle of Ely, a sizable plateau-like hill rising above the nearby fens and considered a potential fortification against advancing Royalists, was given to him as governor on the same day. However, Cromwell was able to stop the Royalist attacks at Winceby in Lincolnshire and then successfully besieged Newark in Nottinghamshire while fighting alongside the parliamentary general Sir Thomas Fairfax. Now that he had achieved these victories, he was able to persuade the House of Commons to raise a new army that would not only defend eastern England but also march out and engage the enemy.

Photo: Encyclopedia Britannica - Oliver Cromwell - Military and political leader

Photo: Art UK -

The son of Walter Cromwell, a yeoman, cloth merchant, fuller, and owner of both a hostelry and a brewery, Thomas Cromwell was born in Putney, Surrey, around 1485. He may not have been a blacksmith, but his use of the alternative surname "Smith" may have contributed to a long-standing custom that he also carried. Walter was elected Constable of Putney in 1495 and was frequently called to serve on juries due to his success as a tradesman. Walter was claimed to be of Irish descent by a knowledgeable but unnamed contemporaneous chronicler, but Norwell, Nottinghamshire, according to biographer James Gairdner, is where the Cromwell family originated. In Staffordshire, Thomas's mother, Katherine Peverell, came from a well-known "gentry family." When she wed Walter in 1474, she was residing in Putney at the home of a local lawyer named John Welbeck.

Cromwell had two sisters: Katherine married Morgan (ap William) Williams, a Welsh lawyer's son who came to Surrey as a supporter of King Henry VII when he established himself in the nearby Richmond Palace, and Elizabeth married William Wellyfed, a farmer. Katherine was Cromwell's older sister. Richard, the son of Katherine and Morgan, worked for his uncle as a servant and, by the fall of 1529, had adopted the name Cromwell.The early years of Cromwell are poorly understood. He is thought to have been born at the peak of Putney Hill, close to Putney Heath.

Photo: Википедия

Photo: The Famous People -

Cromwell became the Member of Parliament for Huntingdon in the Parliament of 1628–1629, as a client of the Montagu family of Hinchingbrooke House. Only one speech (against the Arminian Bishop Richard Neile), which was poorly received, is recorded in the parliamentary records, indicating that he had little impact. Charles, I ruled without a parliament for the following 11 years after dissolving this one. Lack of resources compelled Charles to call another Parliament in 1640 when he had to deal with the Scottish uprising during the Bishops' Wars. As a representative of Cambridge, Cromwell was re-elected to this Parliament, which became known as the Short Parliament because it only lasted three weeks. In 1640, Cromwell relocated his family from Ely to London.

Later that year, a second Parliament was called; it was dubbed the Long Parliament. Cromwell was elected to the Cambridge City Council once more. He most likely obtained his position through the favor of others, as was the case with the Parliament of 1628–1629. This may help to explain why, in the first week of the current session, he was tasked with presenting a petition for the release of John Lilburne, who had become a Puritan cause célèbre following his arrest for bringing religious tracts from the Netherlands. For the first two years of the Long Parliament, Cromwell was associated with the devout group of aristocrats in the House of Lords and Members of the House of Commons, including the Earls of Essex, Warwick, and Bedford, Oliver St. John, and Viscount Saye and Sele. At this point, the group's agenda for reformation included the moderate expansion of freedom of conscience and the executive being checked by regular parliaments. It appears that Cromwell participated in some of this group's political ploys. For instance, he proposed the Annual Parliaments Bill's second reading in May 1641, and he later contributed to the creation of the Root and Branch Bill, which abolished the episcopacy.

Photo: Wikiwand - Long Parliament

Photo: National Army Museum -

It is believed that Cromwell had kidney stones or other urinary/kidney issues. In 1658, after contracting malarial fever, Cromwell was once more afflicted with a urinary infection, which contributed to his decline and eventual death on Friday, September 3, at the age of 59. Coincidentally, this was also the anniversary of his victories during the Scottish campaign of 1650–1651 at Worcester and the Scottish town of Dunbar. Although it's believed that the infection that led to Cromwell's death caused him to develop septicemia, his grief over losing Elizabeth, his supposedly favorite daughter, to what is believed to have been cancer a month earlier undoubtedly accelerated his rapid decline. The funeral for Cromwell was modeled after King James I's, and his daughter was also given a lavish ceremony before being interred in a newly constructed vault in Henry VII's chapel at Westminster Abbey.

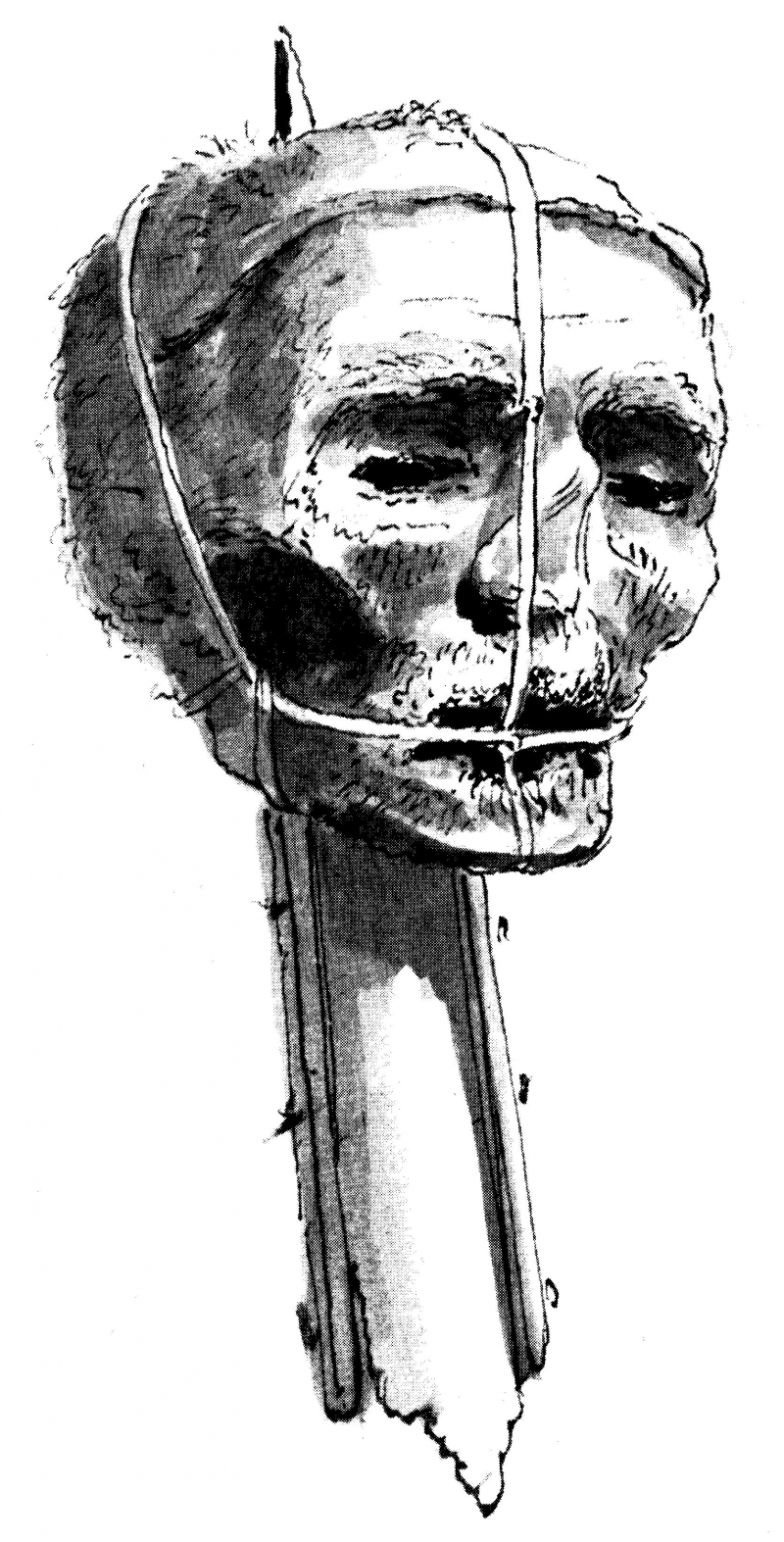

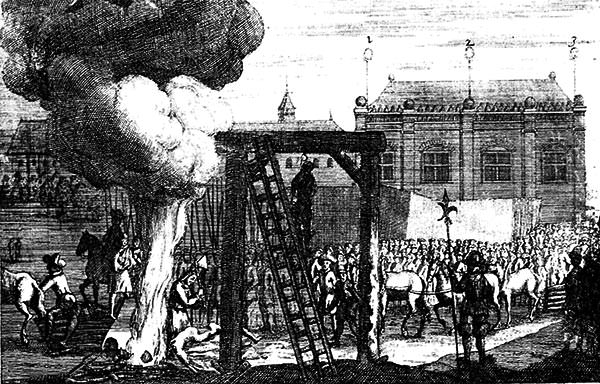

Oliver Cromwell's body, that of John Bradshaw, who presided over the High Court of Justice during King Charles I's trial, and that of Henry Ireton, who served as Cromwell's son-in-law and a general in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War, were all removed from Westminster Abbey on January 30, 1661, in order to be "executed" and put on trial for high treason after their deaths. This symbolic day was picked to fall on Charles I's execution day twelve years earlier. The three bodies were beheaded at dusk after being hung in chains from the Tyburn gallows. The heads were then displayed at Westminster Hall on a 20-foot spike while the bodies were thrown into a common grave. They remained there until 1685 when a storm caused the spike to break and the heads to fall to the ground below.

Unusually, Cromwell allowed the King's head to be reattached to his body at the time of his execution so that his family could pay their final respects to the corpse. A soldier discovered Cromwell's own head after hiding it in his chimney. He left the artifact to his daughter on his deathbed. The head, referred to as "The Monster's Head," made an appearance in a "Freak Show" in 1710. The head was traded around for many years, its value rising with each exchange, until a Dr. Wilkinson decided to purchase it. The Wilkinson family presented the head to Sydney Sussex College, his alma mater, in 1960. It received a respectable burial in a hidden location on the college grounds.

Photo: Wikipedia - Oliver Cromwell's head

Photo: History in Numbers - Cromwell's Execution -

Both in practice and in theory, Cromwell was tolerant. This is demonstrated by his 1655 readmission of Jews to England and his 1653 religious settlement. A large, national Protestant church was established in that year and was funded by tithes and donors. Although there were supposed to be no bishops and Prayer books, the Church of England was not officially disestablished. However, compared to the post-Restoration church, this Cromwellian church, established by the Instrument of Government in 1653, had a higher proportion of clergy and laity. However, some clergy and laypeople consciously chose to remain outside the national church. The more extreme Protestant congregations, like Baptist and Quaker sects, were openly tolerated by Cromwell's government.

In practice, Cromwell's government openly collaborated with the continuation of separate Roman Catholic and Anglican churches, despite the Instrument of Government's prohibition on "Popery and Prelacy's" right to freedom of worship. The Anglican Prayer Book was widely used during Cromwell's reign, and English Catholics experienced greater tolerance than they had since Mary I's death in 1558. 51 Twenty-five Roman Catholics perished as martyrs under James I. Twenty-two Papists lost their lives for their faith during the 1640s period of increased tension. Only two Catholics were executed during the Interregnum, and Cromwell made an attempt to save Father John Southworth in 1654.

Photo: Dictionnaires et Encyclopédies sur 'Academic'

Photo: ZANAMUSIK