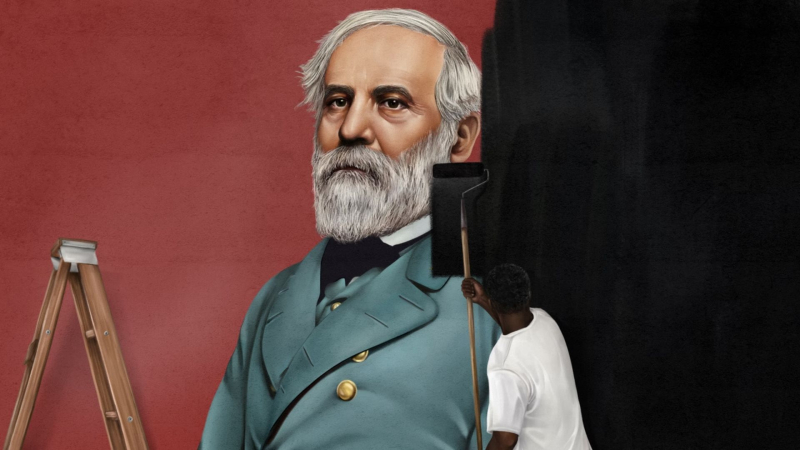

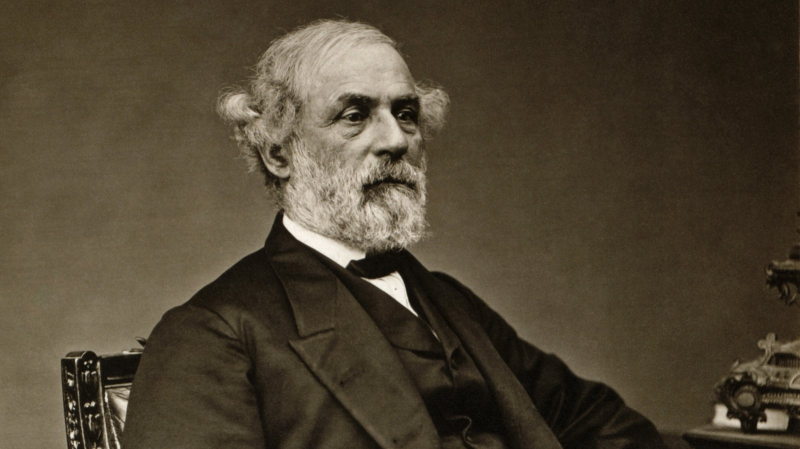

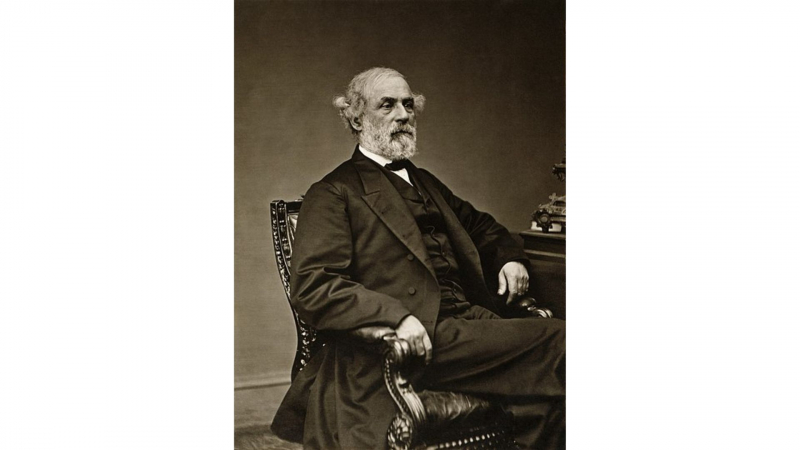

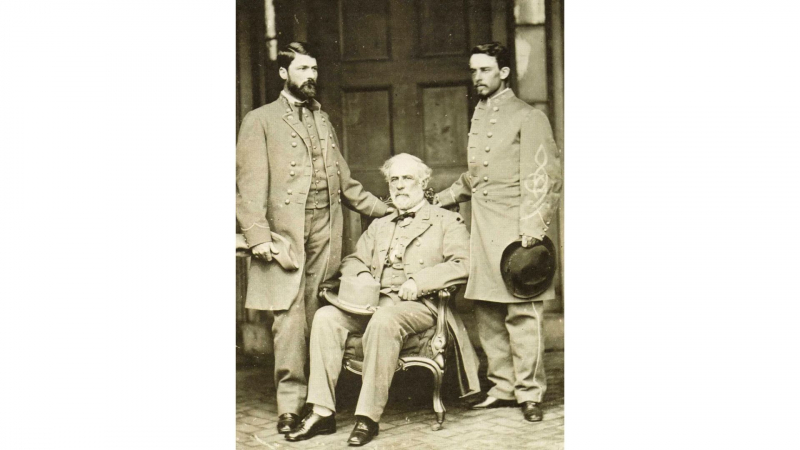

Top 10 Interesting Facts About Robert E. Lee

During the American Civil War, Robert Edward Lee, an American general, oversaw the Confederate States Army. General Lee left behind a legacy that has caused ... read more...controversy and contradictions ever since his passing. On the one hand, he is recognized as having been a successful and moral strategist who fought tenaciously to bring the nation back together following the bloodshed of the American Civil War. Here are some interesting facts about Robert E. Lee - one of the most well-known and divisive historical personalities in the United States.

-

The white abolitionist John Brown assisted fugitive slaves and attacked slave owners. In 1859, Brown made an effort to incite an armed slave uprising. He assaulted and took control of the American arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, with the help of 21 other members of his group.

In less than an hour, a platoon of US Marines headed by Lee overcame him. John Brown became a martyr and a symbol for people who had the same ideals since he was subsequently hung for his crimes. In response to the death penalty, Ralph Waldo Emerson predicted that "[John Brown] will render the gallows magnificent like the Cross."

According to historian Stephen Oates, John Brown "was a trigger of the Civil War... he put fire to the spark that led to the blow up." It has been suggested that John Brown accomplished more for the abolitionist cause by his death and subsequent martyrdom than anything he did while alive.

Source: virginia history

Source: PBS -

One of the interesting facts about Robert E. Lee is that Lee never explicitly spoke out against slavery. Although Lee is frequently seen as being against slavery, he, unlike other white southerners, never outright condemned it. He vehemently criticized abolitionists, saying that they were attempting to "interfere with and transform the internal institutions of the South" through their "systematic and progressive endeavors." Lee went so far as to say that slavery fit within the natural order. He called slavery a "moral and political evil" in a letter to his wife sent in 1856, largely because of the harm it caused to white people.

When Lee's father-in-law passed away in 1857, he inherited Arlington House, where many of the slaves had been misled into thinking that they would be emancipated at the time of his passing. However, Lee kept the slaves and had them work harder to fix the failing estate; he was so strict that it almost sparked a slave uprising. Three of the slaves managed to escape in 1859, and after their arrest, Lee gave the order to lash them extremely hard.

Source: The Independence

Source: The Atlantic -

To the dismay of his staff, Lee nearly never accepted the delicacies that the wealthy locals in the region where his troops camped provided. Lee would surreptitiously convey the food to his soldiers, generally the injured in hospitals, after writing a nice note of gratitude to the donor when fresh fruits or vegetables, great meat, good bread, or even premium spirits were sent to his headquarters. Lee always consumed the standard army ration that was issued to his soldiers along with basic dinners. He also often declined offers to set up shop at Southerners' houses as his headquarters, choosing instead to spend the night outside in a small tent that was, coincidentally, owned by a New Jersey officer who had been captured by the Confederates.

As a result, he made it a point to partake in and get to know his men's everyday struggles as much as he could. One time, Lee was going back to his tent when he saw a soldier looking inside. Lee said, "Walk in, Captain; I am pleased to see you." I ain't no captain, General Lee," the astonished soldier said as he turned to face Lee. I am only a private, and I serve in the Ninth Virginia Cavalry. Lee said, "Well, come on in, sir." "You should be a captain if you aren't already."

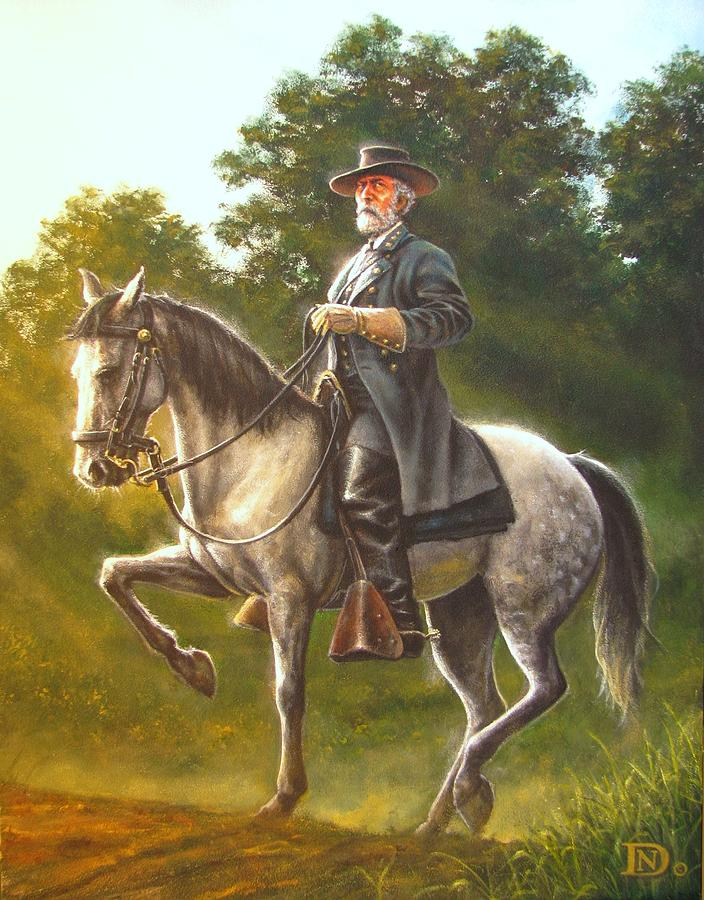

Source: Dale Gallon

Source: Pixels -

One of some interesting facts about Robert E. Lee is that he rode other horses besides travelers during the Civil War. Lee rode other horses during the fight, despite the fact that the iron-gray Traveler may be the most well-known horse in American history. Stratford Hall's website states the following:

Both Richmond, a bay stallion that General Lee obtained in the early months of 1861, and Brown-Roan were already in Lee's stable when he bought Traveler. When he examined Richmond's defenses, the General rode Richmond. In 1862, during the Battle of Malvern Hill, Richmond passed away. Lee bought Brown-Roan in western Virginia during the first summer of the conflict. The horse, also known as "The Roan," had to be retired after going blind in 1862. He had a farmer left behind.

After Lee bought Traveler, two other horses—Lucy Long and Ajax—joined his stable. Lucy Long, a mare, acted as Traveler's main backup. After the war, Lucy Long stayed with the Lee household. She lived longer than General Lee and passed away at the age of 33. Ajax, a sorrel horse, was seldom ridden since Lee couldn't easily ride him due to his size. Ajax continued to live with the Lees even after the war. In the middle of the 1850s, he accidently ran into an iron gate-latch prong and killed himself.

Source: Pinterest

Source: The Saturday Evening Post -

The 200 slaves at Arlington Plantation that had belonged to Lee's father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, were under his management for five years, despite the fact that he had never personally owned slaves. Lee was a strict taskmaster with regard to the Arlington slaves, who had grown accustomed to the lax standards of their late owner, and may have once whipped three escaped slaves. As Lee reportedly noted, "everywhere you see a negro, everything is going down around him, and wherever you find a white guy, you see everything around him improving." He undoubtedly thought that white people were superior to black people.

However, Lee acknowledged that slavery was "a moral and political evil in any society" in a letter from 1858, and after liberation, he embraced the new social realities, treating freed blacks with respect and urging other Southerners to do the same. A black man once dared to kneel before white worshipers at the communion rail in his Richmond Episcopal parish, and he was the first to join him.

Source: The Washington Post

Source: The New York TIme -

Before the war's end, Union soldiers had taken control of the Lees' Arlington mansion; following Appomattox, he returned to a humble home in Richmond that he had rented for his wife and family. Lee sought a means to make a living and give back to society because his legal situation was unclear and he had significantly less money. Ernest B. Furguson notes that Lee declined all opportunities to make a name for himself, including those to lead the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, lead the Romanian army, serve as governor of Virginia, write his memoirs—or simply sign those written by someone else, lead insurance companies, and move into an English manor house with a yearly stipend.

The presidency of Washington College in Lexington, where he would get $1,500 a year plus a share of the total tuition payments the college received, was the job Lee finally found to fit him. By supplementing the existing curriculum of classical education with practical courses in engineering, trade, farming, and the law, Lee revived the failing institution and turned it into a university. This was one of the nation's very few programs in Spanish. Additionally, he founded the nation's first journalism school. According to author Charles Bracelen Flood, Lee is entitled to a position "in the foremost rank of American educators" as a result of his work at Washington College.

Source: the imaginative conservative

Source: Histrory -

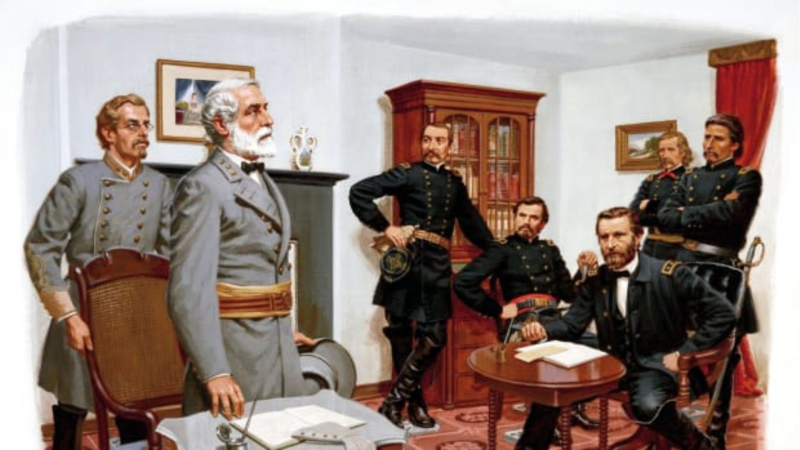

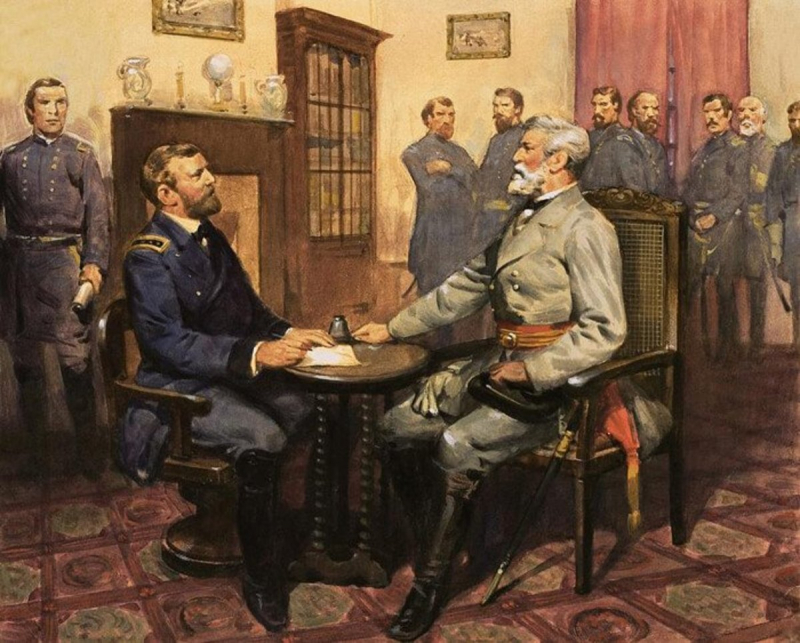

Lee and Grant, who had worked together in the Mexican War before opposing one another in the War Between the States, met on a hilltop between their respective forces the day following their well-known encounter at the McLean House.

Later, when Lee faced the possibility of arrest and execution after being charged with treason by a federal grand jury, he appealed to Grant, pointing out that the clause Grant himself had written into the terms of his army's surrender stated that "each officer and man will be allowed to return to his home, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside." Lee's interpretation was supported by Grant, who pushed Lee to submit an application for a federal pardon, which Grant stated he would support. Lee accomplished this, forwarding the papers to Grant, who approved them and sent them on to President Andrew Johnson.

Although that is a different scenario, the application would be "lost" and Lee's citizenship would not be reinstated until 1975. Lee was unaware that Grant had secretly stated that if Lee were to be imprisoned, he would retire from the army.

Source: National Park Service

Source: LA Progressive -

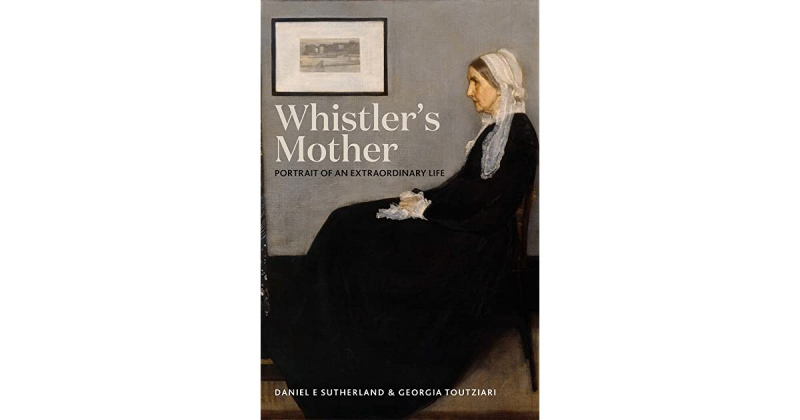

One of some interesting facts about Robert E. Lee corresponded with Whistler’s mother. James McNeill Whistler was a cadet at West Point's Military Academy while Lee served as its superintendent, and he was a very subpar one at that. Lee took a genuine interest in the boy, as he always did with those under his care, even though he ultimately had to expel the "moody and insolent" Whistler from the school after he failed his chemistry class ("If silicon were a gas, I would have been a major general some day," Whistler sarcastically remarked later).

He updated Whistler's mother on his health and emphasized the need for the youngster to be attentive in his efforts in a number of letters to her. The iconic portrait was painted in 1871 by Whistler, who graduated from the Academy and went on to become a well-known artist. Naturally, Whistler rose to fame as an artist after graduating from the Academy, creating the portrait known as "Whistler's Mother" in 1871.

Source: Goodreads

Source: Wikiwand -

Light Horse Harry Lee, one of the heroes of the American Revolution, was a spendthrift and an unsuccessful businessman who had depleted the Lee estate. He was the father he had hardly known. Lee developed a mindset of extreme austerity and meticulous accounting with money after hearing enough tales about his father and witnessing enough of the repercussions of his spending habits on his mother. He once complained in writing to his bank about a $1.20 difference in his account balance of $841.77.

He acquired another poorly managed estate, Arlington House, through his marriage to Mary Custis, a George Washington relative, and it was in a bad state of repair. He put forth a lot of effort over a number of years to make Arlington profitable. Lee was cautious about paying off all of his debts, and at one point during the conflict, he even sent money over the border to pay a blacksmith the $2 he was due.

Source: gettysburg compiler

Source: the imaginative conservative -

Light Horse Harry Lee's prospective father-in-law opposed him when he announced his plans to wed Mary Anna Custis, since Light Horse Harry Lee had had financial difficulty. The Custis family finally gave in. Additionally, Mary Anna Custis was the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington.

Lee was a devoted husband by all accounts, but he also enjoyed the company of attractive young ladies. He even told his wife stories of his interactions with other people of the fairer sex. He cheerfully wrote to his wife Mary, after having the opportunity to entertain the exquisite Harriett Talcott, who was the focus of Lee's particular attention, "How I did swagger about..." How you would have rejoiced in my enjoyment. " By all accounts and depictions of the time, Lee's wife was a plain, if not downtrodden, lady; maybe this reality inspired Lee to win the hearts of more alluring ladies. Lee once told a friend that attractive women caused his heart to "open to them, like a flower to the light."

Source: American Battlefield Trust

Source: Goodreads