Top 10 Interesting Facts about Robert Hooke

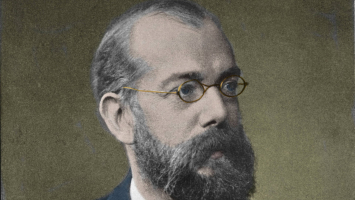

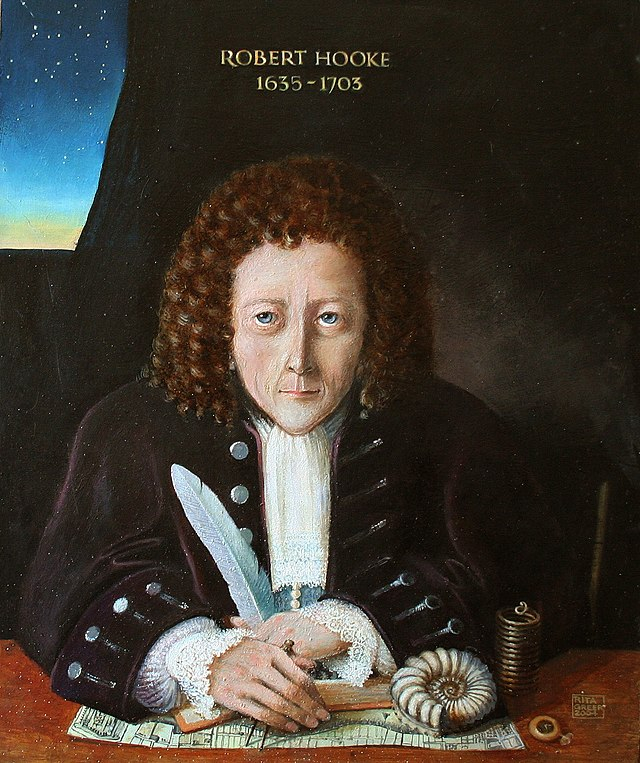

The first person to see a microbe under a microscope was an English scientist and architect named Robert Hooke. In the sciences of physics, geology, ... read more...paleontology, and even astronomy, he achieved important advances. Many people refer to Hooke as "England's Leonardo da Vinci." In this article, we'll take a trip back in time to discover Robert Hooke's life story and accomplishments. Do you want to discover what this scientist has contributed to the field of science? Let's look at interesting facts about Robert Hooke.

-

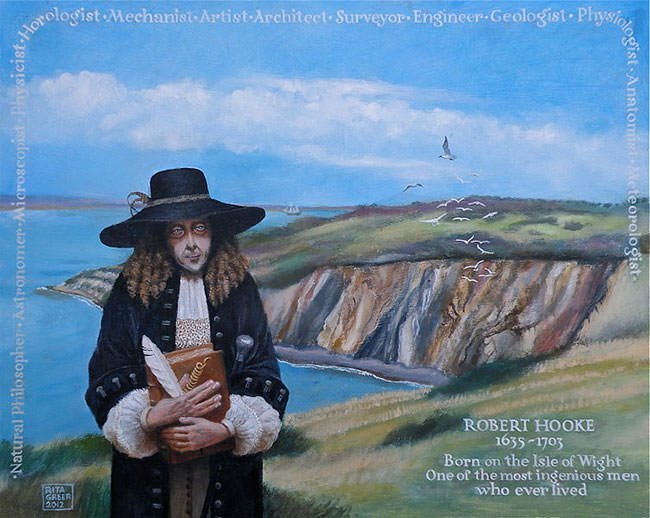

In 1635, Robert Hooke was born on the Isle of Wight, a territory of Great Britain. His father was John Hooke and Cecily Gyles was his mother. John Hooke, who was a curate at All Saints Church in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight, was Robert Hooke's father. John Hooke was left in charge of All Saints even though he was technically a curate since the minister was also the dean of Gloucester Cathedral and Wells. It was a wealthy church since St John's College in Cambridge served as its patron. John Hooke served as a private tutor in addition to managing a small school that was affiliated with the church. The youngest of four children, Hooke was.

Robert's health was bad, as it was for many kids his age, and he was not expected to live to maturity. If Robert had been in excellent health as a youngster, there is little question that he would have continued the family tradition because his father came from a family where it was anticipated that all the boys would enter the church (John Hooke's three brothers were all ministers). As it was, Robert's parents started preparing for his schooling with this in mind, but his persistent headaches made studying difficult. This is the reason why he spent much of his education time at home.

m.apdut.com

m.apdut.com -

One of the interesting facts about Robert Hooke is he had an interest in the arts before becoming a scientist. Since Robert's father started becoming sick about the time he turned 10, he has been allowed to pursue his extremely practical interests in education on his own. Robert showed abilities not just in physics but also in painting. Robert used to observe John Hoskyns, a portrait painter who was employed by Freshwater at the time, while he worked. Soon, he was mimicking Hoskyns' pen and chalk technique and duplicating the artist's portraits. After his father passed away in 1648, Robert's family recognized his potential and decided that the best way for him to support himself would be via art. His family sent him to London to work as an apprentice for portrait painter Peter Lely after his father left him £40 and all of his father's books.

Before Hooke was assigned to him, Lely had already established himself in London after completing his studies at Haarlem in the Netherlands. Lely immediately became well-known for his portraits of James, Duke of York, and Charles I. He developed into England's most technically accomplished painter under the influence of Van Dyck, and Hooke might have learned a lot from such a renowned master. Hooke quickly realized, though, that learning under Lely would be a waste of money and that what he needed was formal education. Hooke enrolled in Westminster School and boarded with Richard Busby, the school's headmaster. Hooke was lucky to be influenced by Busby, an excellent instructor who immediately realized he had a very exceptional student. By the end of his first week at school, Hooke had mastered the first six books of Euclid's Elements, but Busby appeared to recognize that conventional education was not going to be ideal for Hooke and encouraged him to study independently in his library.

Hooke studied Latin and Greek at Westminster, but unlike his contemporaries, he never wrote in the language, despite enjoying speaking it. He quickly applied his newly acquired geometrical knowledge to his genuine passion for mechanics and started to come up with ideas for potential flying aircraft. He had other hobbies as well, including music. He attended an organ course at the start of his Oxford studies and was accepted into the Christ Church chorus. When he felt he had learned everything Westminster School had to offer in 1653, he enrolled in Christ College in Oxford and was given a place as a chorister.

theconversation.com

theconversation.com -

Since he was a child, Robert's original concepts used both his mechanical and observational abilities, which is one of the interesting facts about Robert Hooke. Around him, he took note of the surroundings' vegetation, fauna, farms, cliffs, sea, and beaches. He made various items out of wood, ranging from a model of a fully equipped ship with operating weapons to a functional clock since he was attracted by mechanical toys and clocks. Waller dates Hooke's conviction in mechanics, and particularly his idea that nature was a complex machine, from the time he allowed his imagination and his skills to run wild at around age ten, in the Preface to Hooke's Posthumous Works, which was published in 1705.

When in Oxford, Hooke studied astronomy under Seth Ward and dazzled Wilkins with his mechanical prowess. A copy of Wilkins' book Mathematical Magick, or the miracles that may be worked by mechanical geometry, which he had written five years before Hooke arrived at Oxford, was given to him. This book inspired Hooke to pursue his goal of creating a flying machine, and he carried out pulley experimentation at the Wadham College grounds. Hooke helped Willis with his dissection experiments for a period. He collaborated with the leading English scientists of the day and benefited significantly from learning a variety of fields.At the age of 20, Hooke moved a step closer to becoming a scientist in 1655. His proficiency with mechanical equipment had advanced to the point that he was able to gain employment in Oxford as Robert Boyle's assistant, who was one of the fathers of modern chemistry. Boyle used apparatus that Hooke mostly conceived and built to uncover Boyle's Law throughout their seven-year collaboration. The anchor escapement, which Hooke created about 1657, significantly enhanced the pendulum clock. This gear advanced the clock's hands while providing a tiny push to each pendulum swing to keep it from running out of energy. The balancing spring, which is essential for precise timekeeping in pocket watches, was created by Hooke around 1660, and he even manufactured one for himself. Since a pendulum cannot be employed in a pocket watch, an alternative method of keeping track of time is required. Time could be accurately preserved by using Hooke's balancing spring, which was connected to a balance wheel and created a regular oscillation. Over ten years later, Christiaan Huygens independently developed the balancing spring. Hooke's Law, which asserts that the tension force in a spring rises in direct proportion to the length it is stretched to, was discovered in 1660.

commons.wikimedia.org

commons.wikimedia.org -

A booklet on capillary action was Hooke's first piece of writing. His report, which demonstrated that the higher the water ascended in the tube, the narrower it was, was read to the Society on April 10th, 1661. By this point, the Gresham Society had requested from King Charles II recognition and a royal grant of incorporation. A Curator of Experiments was to be appointed by the terms of the Royal Charter, which established the Royal Society of London and was approved by the Great Seal on July 15, 1662. The Society had previously planned to name Hooke to this post, and on November 5th, 1662, he was awarded the job. In many respects, it didn't seem like a great lot because he was expected to present three or four experiments at each Society meeting, which was completely unreasonable and unlikely to be accomplished by anybody other than Hooke. Hooke was compelled to complete the task without payment until the Society was in a position to do so, even though it was believed that they would eventually be able to compensate him.

In reality, over the next 15 years, Hooke responded to the impossible job given to him by coming up with a ton of innovative ideas. Society indeed flourished as a result of Hooke's stream of ideas, but the demands also fully exploited Hooke's talent. On the one hand, it appeared to fit his character to have his thoughts hop from one half-formed notion to the next, even if the demands meant that he never had time to develop his ideas over time as one would expect a renowned scientist to do. On June 3rd, 1663, he was elected to the Royal Society, and although he was still not being paid, the Society was willing to let him become a Fellow without having to pay the annual dues.

The Society agreed to pay Hooke £80 per year in salary in 1664, but shortly afterward they arranged for him to hold the position of Cutlerian Lecturer in the Mechanical Arts at a salary of £50 per year. Later, they decreased his salary to £30 per year as Curator of Experiments while appointing him to a position for life. As a result, this did not give Hooke the financial security he might have hoped for. The Society frequently did not have enough money to pay Hooke as Curator of Experiments, and when he wasn't paid for his duties as Cutlerian Lecturer in the Mechanical Arts, he was forced to go to court to get payment. Nevertheless, he managed to acquire another position, as Professor of Geometry at Gresham College in London, where he was appointed in 1665. He was given college housing in exchange for delivering one lecture every week during the academic year. It was necessary to deliver the lecture in Latin before repeating it in English. In December 1691, Hooke got the title "Doctor of Physics."

commons.wikimedia.org

commons.wikimedia.org -

Hooke was the first to construct a Gregorian reflecting telescope, which is one of the interesting facts about Robert Hooke. He created the earliest known description of the planet Uranus using this telescope. He also developed several theories concerning the rotation of Jupiter and gravity, as well as the first double-star system, known as Gamma Arietis. He then created a helioscope to use sunspots to gauge the sun's spin. He created sketches of Mars that were eventually used to calculate its rotational period. He witnessed multiple comets and posed several significant concerns regarding them, such as why the tail of each comet faces away from the sun and how a comet that is burning could continue to burn for so long in an environment devoid of oxygen.

Hooke not only found Uranus, but Hooke also developed the Theory of Planetary Motion. He came up with the idea after solving a mechanical puzzle. One of the strongest postulates he made in expressing the laws of universal attraction was that all bodies travel in a straight line until they are deflected by another force, which will cause them to move in the form of a circle, ellipse, or parabola. He said that everybody has their gravitational pull at its center or axis and that this pull is amplified by the gravitational pull of other celestial bodies in the area. This power of attraction impacts us more the closer we are to other celestial bodies. Additionally, he made an effort to confirm that the Earth orbited the Sun in an ellipse. All of this contributed greatly to the advancement of science and space observation.

study.com

study.com -

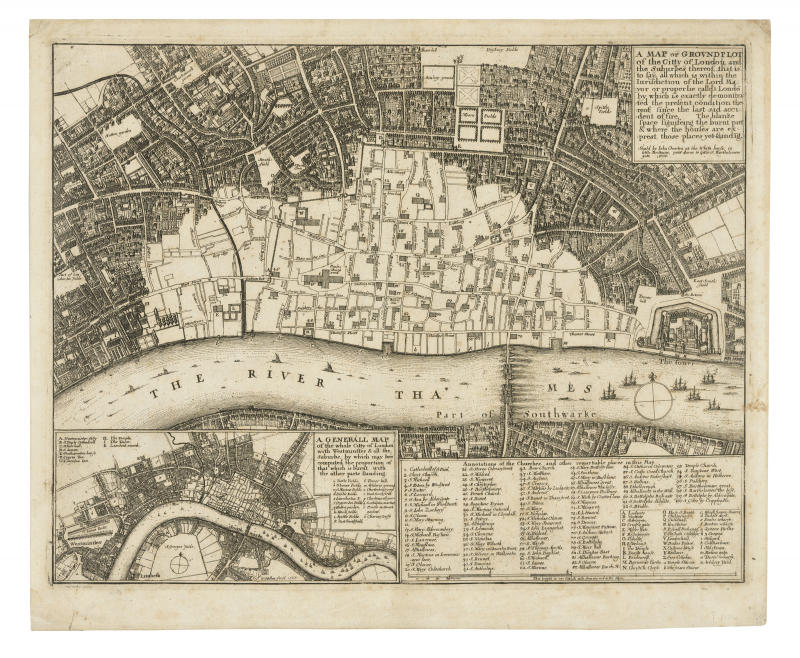

Hooke pursued a second profession as an architect in addition to his work as a scientist, which is one of the interesting facts about Robert Hooke. He was crucial in helping to reconstruct London following the Great Fire (1666). There was an urgent need to rebuild the City of London. The King nominated three people, Wren being one of them and the City appointed three others including Hooke to manage and carry out this massive undertaking. He rose to the position of Surveyor for the City of London, working with renowned architect Christopher Wren as his principal assistant. Hooke was heavily involved in every phase of the reconstruction of London, including the practical (widening streets and defining property lines) and artistic (designing churches and civic buildings). His construction designs were well received, he created many of the structures that stood in for those lost by the Great Fire of London in 1666, he made a lot more money as an architect than as a scientist.

Besides, the Monument to the Great Fire is a brilliant illustration of Hooke's inventiveness, even though very few of his architectural creations have lasted the test of time. Its design as a monument, a column sitting on a prism is rather traditional, but it is clever when used as a scientific tool. Hooke was doing research into the earth's motion and the calculation of gravity during the time the monument was being created. The monument was built to include a gravity "lab" and a zenith telescope to advance study. Additionally, The Royal Greenwich Observatory, Montagu House in Bloomsbury, Bethlem Royal Hospital, the Royal College of Physicians, and many more buildings were among the projects he worked on.

www.rmg.co.uk

the Monument to the Great Fire - www.westminster-abbey.org -

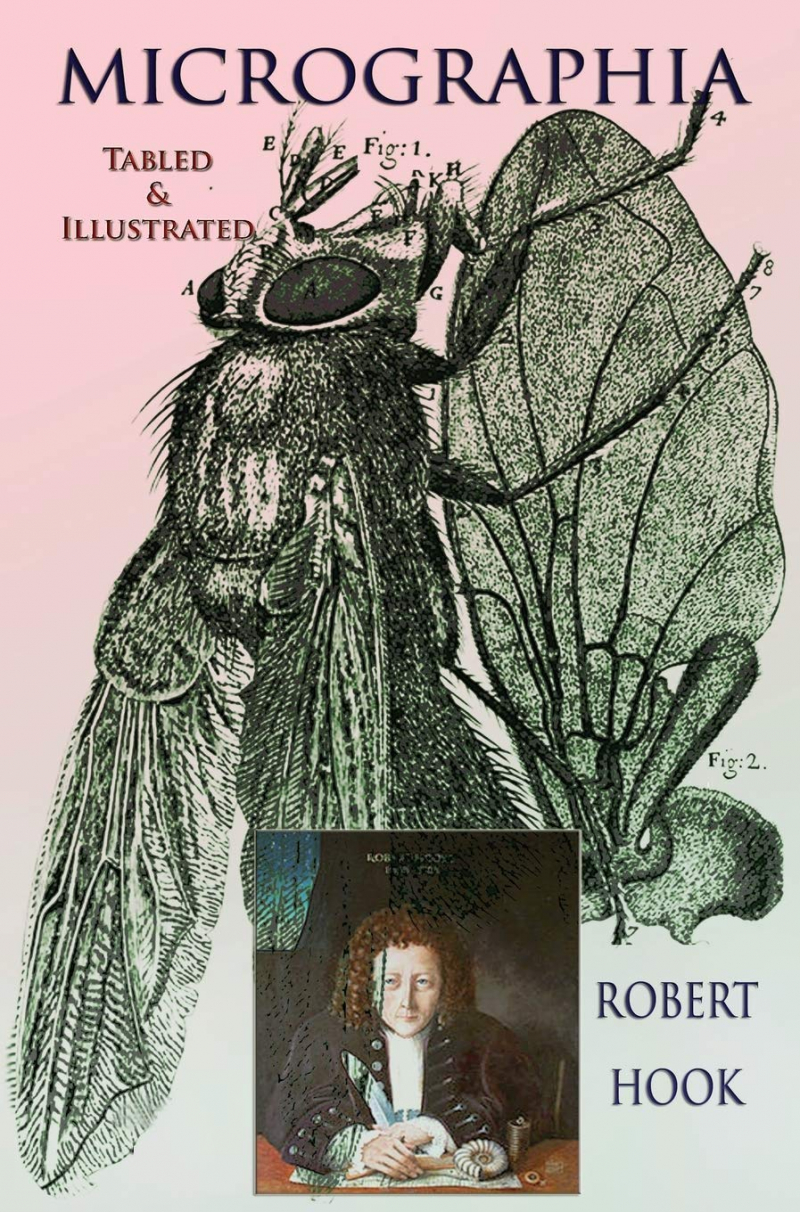

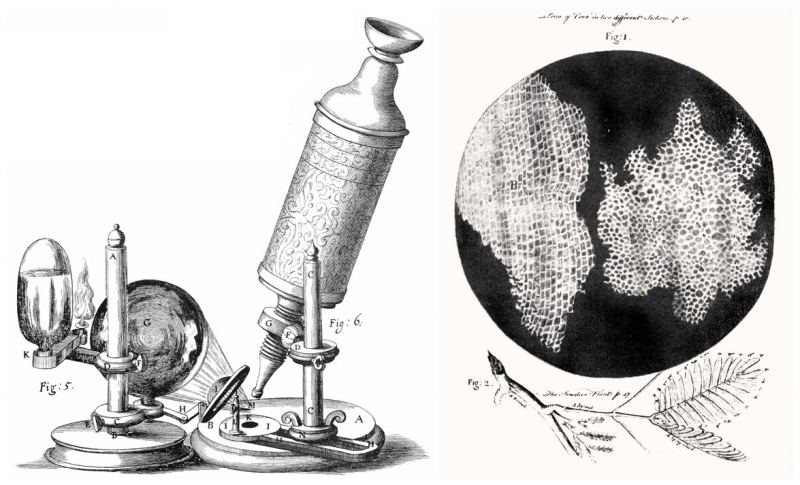

Hooke published Micrographia, the first scientific blockbuster ever in 1665 when he was 30 years old. Micrographia showed a brand-new universe that no one had ever thought was possible. The book served as a display of Hooke's unique capabilities, including his grasp of nature and light, his highly developed scientific instruments, construction skills, and his abilities as an artist.

Hooke created a novel, screw-operated focusing mechanism and built a compound microscope with it. Before, the specimen had to be moved to be in focus. He added illumination to the microscope to make it even better. To brilliantly illuminate his specimens, he set up an oil lamp next to the microscope and a water lens to concentrate the light on it.

Hooke examined the tiniest, hitherto unnoticed aspects of the natural world with his microscope. In the form of tiny fungus, Hooke found the first known microorganisms in 1665. This came nine years before Antonie van Leeuwenhoek discovered single-celled life. Hooke examined the microscopic structure of the cork tree's bark. In the process, he discovered and gave the term "cell" to the basic unit of life. He believed the things he had found resembled the distinct cells, or chambers, found in monasteries. Hooke never identified the real biological purpose of cells.

Besides, Hooke examined the ancient cells in the petrified wood with his microscope. He concluded that fossils were once living organisms whose cells had become minerals. He also concluded that certain extinct species must have previously existed. Although practically everyone today accepts this, his proposition was unpopular when it was first presented. According to Hooke's Micrographia: "Nothing is so far away that it cannot be seen through the use of telescopes, and nothing is so little that it cannot be studied through the use of microscopes. As a result, a new visible World has been made known to humankind."

Micrographia - www.amazon.es

www.atlasobscura.com -

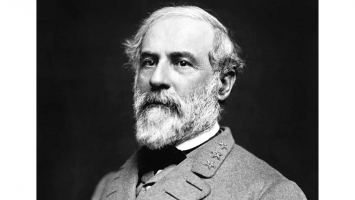

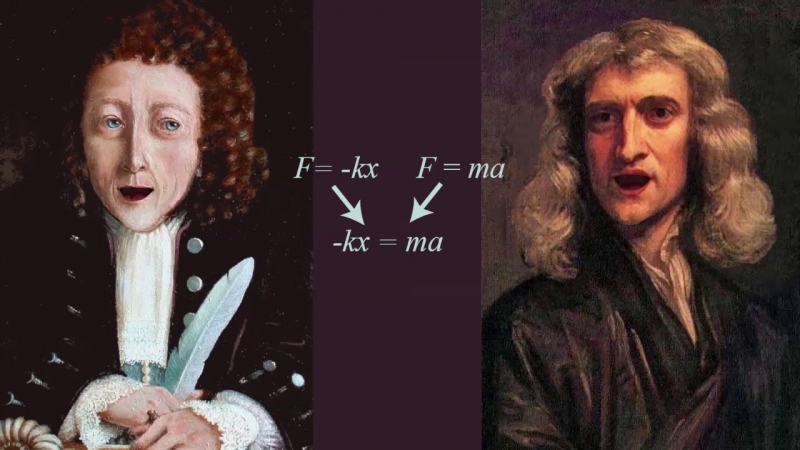

In his later years, Hooke grew more irritable and got into a lot of arguments with other scientists, frequently over who said what first. Isaac Newton and Hooke had one of his most well-known disputes, which is one of the interesting facts about Robert Hooke. Hooke stated that what was accurate in Newton's theory of light and color in 1672 was taken from his views about light in 1665 and that what was original was incorrect. In 1672, Hooke made an effort to demonstrate that the Earth orbits the Sun in an ellipse. Six years later, he suggested the inverse square law of gravity as a theory to account for planetary motions.

But starting in November 1679, he began writing to Isaac Newton and sharing some of his newer discoveries. Newton introduced his hypothesis of this law in his 1686 book Principia. The argument arose from Hooke's assertion that he had introduced Newton to the idea of the inverse square law. Newton eventually realized Hooke had first put out these concepts. But Hooke didn't appear to be able or perhaps he wasn't willing to provide a mathematical justification for his hypotheses. He also highlighted that other scientists had also done it, but that he had established all the data and the mathematical demonstration, not Hooke.

Hooke's life was filled with numerous, acrimonious arguments with other scientists. On the other hand, it's important to note that he got along well with several of his coworkers, especially Boyle and Wren. In many respects, historians' assessment of Hooke as a difficult and unreasonable guy is unfair. Without a doubt, Hooke sincerely believed that his original ideas had been copied by others. It's simple to understand why this occurred. Hooke had a wide variety of remarkable ideas, many of which were later claimed by others not because they wanted to steal them from him, but rather because Hooke never pursued them to construct whole theories. Because he lacked the technical know-how to create such thorough theories as some of his contemporaries like Newton and Huygens, he was unable to produce any significant theories from his inspired thoughts.

www.writerstheatre.org

www.writerstheatre.org -

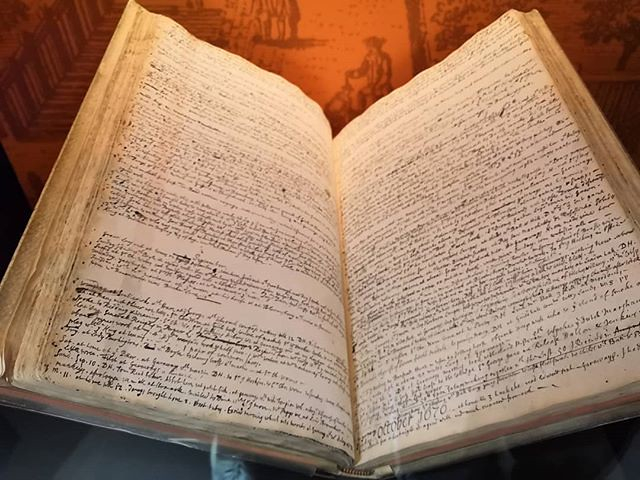

One of the interesting facts about Robert Hooke is he has a diary, although not as literary as Samuel Pepys, also Hooke's diary makes a significant contribution to both London architecture and scientific inquiry in the 17th century. The diary provides an unmatched look into the exciting and vibrant world of scientific discovery and the rebuilding of London from the ashes of the Great Fire. It was kept as a memorandum book to remind him of the numerous places he had been and people he had met each day, as well as his witty thoughts and observations about scientific research and the world around him.

Hooke could be frank in his remarks about himself and his contemporaries since he did not intend for anyone else to read his journal. A guy tries to be open and honest with himself, as seen in the journal. He took note of his symptoms and the experimental, occasionally risky medications he self-administered because he believed that his body and habits were worthy of examination and research.

The evidence from his diary reveals he was frequently both social with many evenings in taverns and coffee houses documented and collaborative, working closely and amicably with many colleagues. He was known for his irascibility and scientific arguments. Other times, he confessed in the journal his resentment of scientists whom he felt had stolen his concepts and inventions or purposefully understated his contributions and accomplishments. The entries in the journal have allowed historians to shed light on these traumatic arguments and explore the various lines of inquiry he was pursuing across a wide range of subject areas. The diary has been added to the UK Memory of the World Register by UNESCO.

www.flickr.com

www.flickr.com -

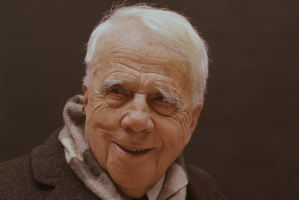

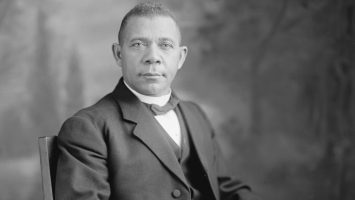

Robert Hooke spent most of his adult life in his native Isle of Wight, Oxford, and London. He never got married, but he did have a love connection with his housekeeper and longtime live-in companion Grace Hooke, his niece. He was friends with Robert Boyle, Sir Christopher Wren one of the most renowned builders in history, and John Aubrey an English naturalist and writer. On March 3, 1703, he passed away in London at the age of 67. In his room at Gresham College, a box containing gold and cash worth 8,000 British Pounds was discovered. He had discussed giving the Royal Society a gift that would have funded a lab and library in his honor before he passed away.

Robert Hooke left his remaining cash and gold to his cousin Elizabeth Stephens because there was no such will to be located. Although his bones were interred in St. Helen's Bishopsgate, the location of his burial is still a mystery. A few months after Hooke's passing, Newton was elected to lead the Royal Society, and preparations for a new headquarters were made. When they relocated, Hooke's portrait vanished and was never recovered. As president of the Royal Society, Isaac Newton neglected to save (or destroyed) his sole surviving portrait. Hooke's reputation suffered after his passing as a result of his disagreements with other scientists, but now he is regarded as one of the most significant scientists of his time.

www.britannica.com

www.britannica.com