Top 10 Interesting Facts On The Greek God Of Wine - Dionysus

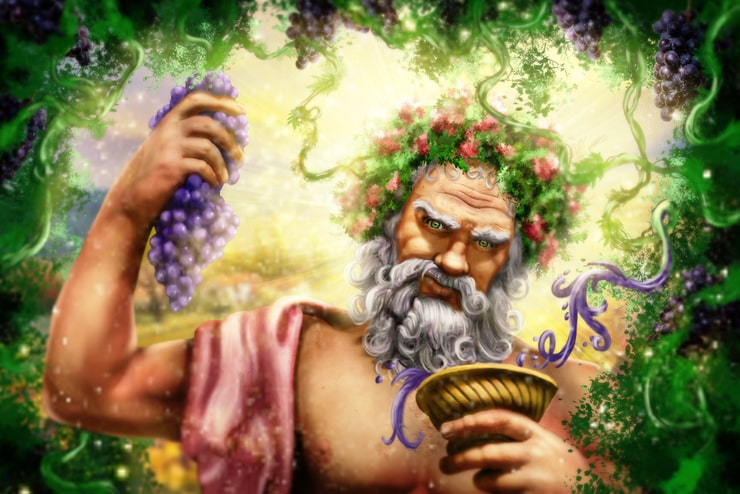

Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, was a significant figure in ancient Greek culture. Many people are familiar with Dionysus as the Greek god of wine, but few ... read more...are aware that he was a vital player in not only wine consumption, but also early viticulture and fertility, and that he was honored by the ancient Greeks with spectacle and festivity. Here are the ten most interesting facts on the Greek god of wine - Dionysus that you can share with your wine-loving pals.

-

One of the most interesting facts on the Greek god of wine is Dionysus had three births. The birth myths of many Greek gods are well-known. For example, Athena was rumored to have been created from Zeus's head after he swallowed his first wife, Metis. Dionysus has numerous birth tales, which are unique. Different local traditions emerged as a result of the legends of his birth being told at a time when there was no one official religion. Writers would eventually strive to weave these stories together into a single cohesive story.

Dionysus' initial birth, according to the account cobbled together from several local myths, occurred early in the gods' history. In a myth cherished by several mystery cults, Zeus journeyed to the Underworld and conceived a child with Persephone.

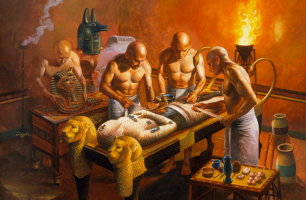

Dionysus' original incarnation was shown as a bearded guy. He possessed large horns because, according to legend, he taught humanity how to tame oxen and utilize them to plow their fields. This Dionysus was Zeus's favorite son. Zeus brought him to Olympus and placed him on his throne intending to make him his heir. Hera, on the other hand, was enraged that Dionysus was given preference over her son, Ares. She enlisted the Titans' aid in attacking and dismembering Dionysus. Many Titans were imprisoned in Tartarus in this account, not because they fought Zeus in the Titanomachy, but because they killed his son. According to one story, they had mutilated him so thoroughly that just a few parts of his heart could be located by Athena. Zeus concocted an elixir containing the god's essence from these little shards. He gave this elixir to Semele, a mortal maiden. She was a priestess in some traditions, while others believed she was the daughter of Harmonia and Cadmus.

Dionysus' second birth story is the more well-known of the two. Semele became pregnant with Zeus's child and drew Hera's notice as she welcomed the birth of her celestial child. Hera pretended to be Semele's nurse, Beroe and counseled the girl to make her lover prove his identity by revealing his true appearance. Zeus fought back at first, but eventually showed Semele a glimpse of his heavenly nature. This was enough to break the mortal psyche of the girl. Semele died when she erupted into flames.

However, Zeus was able to save the infant by cutting him out of her womb. He sewed his son into his thigh till he was big enough to be born because the baby was still immature. As a result, Dionysus was known as the god who was born three times. Persephone gave birth to the first child, Semele to the second, and Zeus to the third.

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/ -

Dionysus was viewed by early Greek scholars as a foreign divinity who was hesitantly admitted into the Greek pantheon of gods. Recent discoveries, however, suggest that his devotion to Greece predates what we now know as ancient Greek civilization. This leads us to believe that, even if his cult was imported, it was far ahead of what was previously accepted.

Excavations in and around the Palace of Nestor at Pylos in the early and mid-twentieth centuries uncovered the first written documents of the Dionysian cult. Recovered shards of clay tablets from around the 13th century BCE Mycenaean Greece show his name written in Linear B as di-wo-nu-su-jo ("Dionysoio" = 'of Dionysus'). These could be offerings to the deity during that period. Other allusions to "ladies of Oinoa" and "place of wine" are thought to confirm this theory.

Dionysus was one of the first gods attested in mainland Greek culture, according to more recent evidence. The first documented accounts of Dionysus worship originate from circa 1300 BC in Mycenaean Greece, specifically in and around the Palace of Nestor in Pylos.

Photo: https://truyencotich.vn/

Photo: https://blog.wiccamagazine.com/ -

Dionysus was nurtured in secret to avoid Hera's wrath, according to tradition. He was raised by wood and river nymphs far from Mount Olympus. Hera, on the other hand, discovered him when he was an adult. She hit her stepson with lunacy, just as she had Heracles.

Dionysus wandered the globe for many years, forgetting who he was and what his purpose was. He made wine grow wherever he went because he was still a god, and according to certain mythology, he was tied to the fertility goddess Persephone. To the Greeks, this explained why grapevines could be found all over the earth. Dionysus had unintentionally planted them as he roamed.

Rhea eventually tracked down Dionysus and cured him of his insanity. He returned to Olympus, although he still traveled the world on occasion to tend to the vineyards he had planted. Dionysus' role as the deity of madness was established in this episode. He could inspire a comparable state of mind to deliver either bliss or pain to others, having been driven insane himself.

Dionysus, according to legend, continued to tour the world when his wine grapes bloomed. According to Nonnus' epic from the fifth century, Zeus dispatched Dionysus on a military campaign to convert the inhabitants of India to his devotion. He was mostly successful because he introduced wine to the country, accompanied by an army largely made up of satyrs and maenads.

Although the Dionysiaca was not written in Classical Greece, there is evidence that the Romans had a more militant concept of Dionysus/Bacchus at an earlier time. The Roman triumphs that celebrated victorious generals and the emperor were inspired by his procession of followers.

Photo: https://wine.lovetoknow.com/

Photo: https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/ -

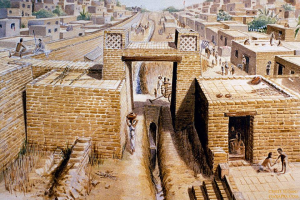

The earliest known image of Dionysus survives on pottery, which is one of the most interesting facts on the Greek god of wine. Dionysus was one of the first gods mentioned in mainland Greek culture, according to new evidence. The details of any religion associated with Dionysus during this period are scarce, and the majority of evidence consists solely of his name. The oldest known depiction of Dionysus, as well as his name, was discovered on a dino by the Attic potter Sophilos circa 570 BCE. The wedding of Peleus and Thetis is depicted in the items, with Peleus receiving the wedding guests at his home, including Dionysus. The artist's signature "Sophilos painted me" may be found between the columns of Peleus' dwelling.

Dionysus worship may have been firmly established by the 7th century BCE, according to other iconography found on pottery. He was not just the God of Wine during the time, but also of weddings, death, sacrifice, and sexuality. The transformation of the god's worshippers into hybrid creatures, commonly represented by both tame and wild satyrs, indicated the move from civilized life back to nature as a means of escape in these early images. Furthermore, his satyrs and dancers had already been assembled.

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/

Photo: https://religion.fandom.com/ -

While the Romans depicted Dionysus triumphantly, many of his myths depicted him as an outcast. Dionysus was a deity of craziness and festivity, and his devotees were notorious for behaving badly. The maenads were supposed to be so enamored of him that they would rend men to shreds if they interfered with their rites. As a result of these factors, Dionysus' mythology is littered with tales of Greek cities being unwelcoming or even hostile to the hedonistic god.

Dionysus attempted to return to his mother's hometown of Thebes after his consciousness was restored in Euripedes' drama The Bacchae. The kind, who was his cousin, refused to believe in his divinity and spoke out against his influence on the city's women. Dionysus punished King Pentheus by driving him insane and leading him to the woodland where the maenads were having their secret revels. In their rage, the maenads attacked him, and his mother killed him.

For imprisoning the maenads in his realm and threatening Dionysus, the king of Thrace was likewise horribly punished. The god sought sanctuary with Thetis and cursed Thrace with a drought. After that, he drove the king insane. King Lycurgus dismembered his son with an ax, mistaking him for a cluster of ivy. Dionysus then disseminated a rumor across Thrace, claiming that as long as Lycurgus remained, the area would be cursed with drought and misfortune. The people revolted against him, and the monarch was assassinated by a mob.

Dionysus is only welcomed by those who have no idea who he is in various myths. According to at least two accounts, Dionysus was kidnapped by pirates who mistook him for a wealthy human prince or kidnapped him to sell him into slavery. These stories proved his divinity, which was sometimes questioned in his legends.

Photo: https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/

Photo: https://learnodo-newtonic.com/ -

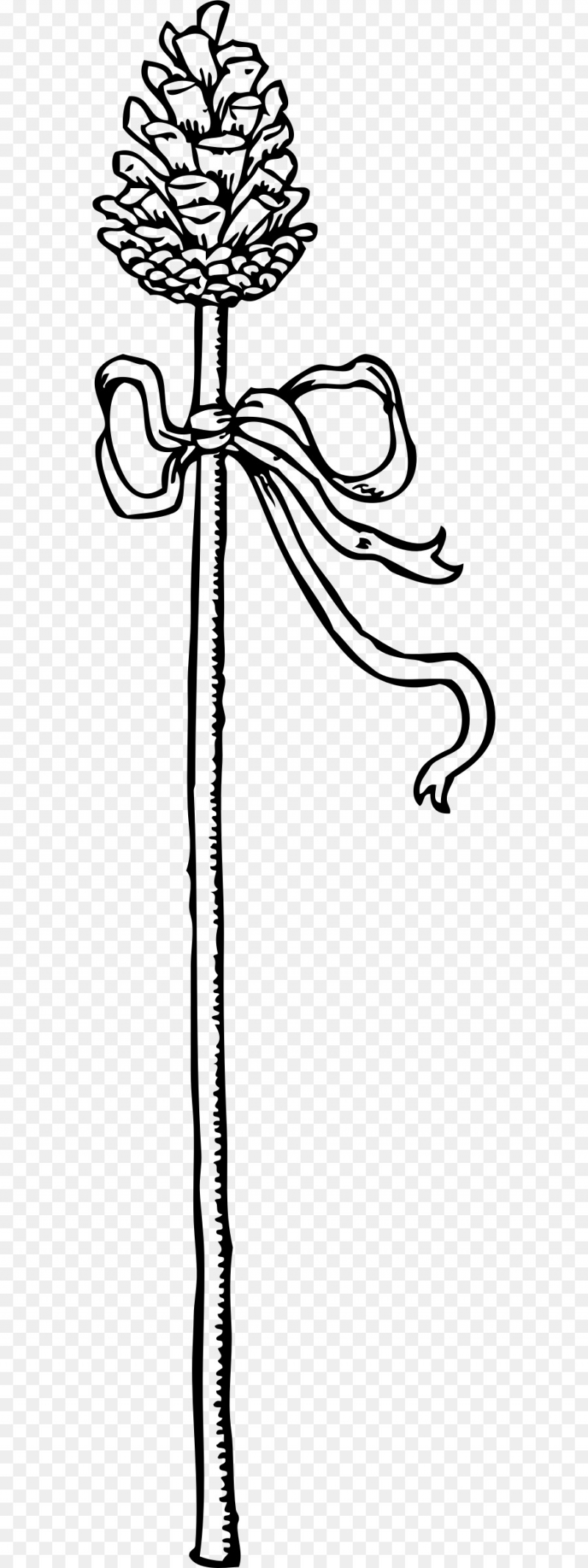

Dionysus and his followers are frequently depicted carrying a thyrsus, a popular emblem associated with God, in art, iconography, and literature. The thyrsus is a huge fennel wand or staff wrapped in ivy vines or leaves. A pinecone, a cluster of vine leaves and grapes, or ivy leaves and berries were commonly used to top it. Just below the pine cone or the group of leaves, a riband or fillet can be found linked to it. The thyrsus was a sacred instrument in Greek rituals and ceremonies and was seen as a symbol of prosperity, fertility, and an overall delight.

This is thought to be Dionysus' mystical stuff. Dionysus can use this magical tool to change the rock into the water. The thyrsus was also employed by Dionysus to turn water into wine, and the tip of the thyrsus was thought to cause insanity. The thyrsi can also be used as a weapon ("a spear wrapped in vines"). For example, in Euripides' play "The Bacchae," the main heroine Agave kills her son by impaling his skull on Dionysus' thyrsus by accident. Baccus (Dionysus) and his disciples are also shown giving the thyrsus in Ovid's Metamorphoses Book III.

Photo: https://en.wikipedia.org/

Photo: https://vi.cleanpng.com/ -

The legend of King Midas is still popular today, but many people are unaware that it was Dionysus who bestowed his golden touch on the famed leader. Silenus, the elderly satyr who had raised Dionysus in his youth, went lost, according to tradition. He'd passed out drunk on King Midas' land and been discovered by peasants. Silenus was greeted warmly by the monarch, who lavished him with hospitality. Before Midas returned the satyr to Dionysus, they feasted together for ten days and nights.

In exchange for the king's good treatment of his friend, Dionysus offered him anything he desired. Midas begged that everything he touched turn to gold without even thinking about it. Midas was granted the favor, but the god of wine told him that he wished he had made a wiser decision. The monarch, on the other hand, was overjoyed when a leaf turned to gold when he touched it. Midas suddenly saw the folly of his decision as the kingdom got wealthy. When he tried to eat or drink, the food turned to the metal as soon as it came into contact with his lips.

Photo: https://greekreporter.com/2021

Photo: https://iagtm.pressbooks.com/ -

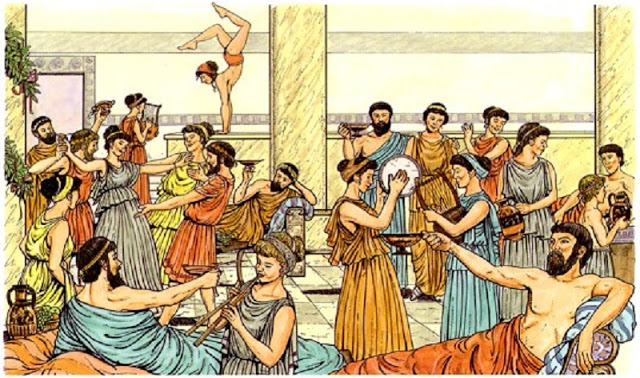

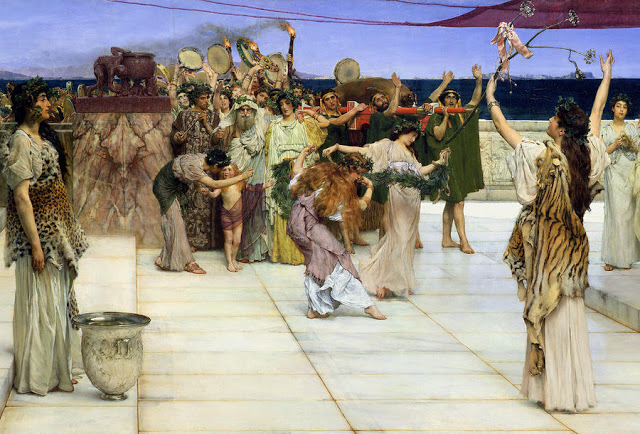

Dionysia, Haloa, Ascolia, and Lenaia were four separate ancient Greek festivals honoring Dionysus, the God of Wine and Festivity. The most ancient of them all is "Rural Dionysia," which took place in the Attic month of Poseideōn (late December). This celebration commemorated the planting of vines, which was accompanied by singing, dancing, and wine consumption. This celebration led to the creation of the "City Dionysia" festival (perhaps 6th century BCE), which was held three months after the rural Dionysia and was likely to commemorate the end of winter and the harvesting of the year's crops. Between and around the two Dionysia celebrations, smaller agrarian festivals such as Anthesteria, Lenaia, Ascolia, and Haloa were celebrated.

- The Lenaia festival took place in January in Athens and featured processions, singing, and unique rites performed by women.

- In the month of Anthesterin (January/February), Anthesteria was held near the full moon.

- Ascolia was more of a religious feast in which the goat was sacrificed and games were played in honor of God.

- Haloa was an agrarian festival held after the first harvest in the month of Poseiden (December/January). The event was largely observed by women and was devoted to Demeter, Dionysus, and Poseidon.

Photo: https://greekerthanthegreeks.com/

Photo: https://greekerthanthegreeks.com/ -

The "Theatre of Dionysus" in Athens, discovered in the 1800s by German architect and archaeologist Wilhelm Dorpfeld, is considered the world's oldest theater. The ruins of the theater lay exactly north of the shrine of Dionysus on the southern slope of the Acropolis hill in Athens. The majority of the surviving ruins date from Lycourgos' massive theater construction in the second half of the 4th century BCE.

The theater had achieved its maximum capacity at this point, and it could have sat up to 17000 people. The core of the theater is thought to date from the sixth century BCE. During the 5th century BCE, the Dionysian festival of City Dionysia (Greater Dionysia) became strongly tied with Greek theater. Sophocles, Euripides, Aeschylus, and Aristophanes were among the ancient playwrights who presented their works here. These plays are credited as being the catalyst for the creation of theater in Western culture.

Only 20 of these parts have been maintained to this day. Some of the thrones include inscriptions indicating that they belonged to chosen monarchs, while others were intended for citizens. The most magnificent seat, however, was carved with grape bunches and the phrase Priest of Dionysus Eleftherius. Over the last few years, significant efforts have been made to rehabilitate Dionysus' old theatre so that it can once again stage theatrical performances.

Photo: https://www.itinari.com/

Photo: https://www.mozaweb.com/ -

On the Greek god of wine Dionysus’s festival Bacchanalia was suppressed in Rome, which is one of the most interesting facts about Dionysus. The Bacchanalia was a famous unauthorized Bacchus (Dionysus) holiday in Roman times, based on the different euphoric features of the Greek Dionysia. The particular ceremonies conducted during the holiday are difficult to determine because it is celebrated in private groups. The Roman authorities, on the other hand, mercilessly suppressed the Bacchanalia in 186 BCE. In the 39th book of his 'Ab urbe condita,' the ancient Roman historian Titus Livius (59 BCE – 17CE) states that 7000 persons were killed in the campaign, with many of them executed. He also claims that the measures created a great deal of fear both inside and outside of Rome.

There were also several suicides and a large exodus from Rome. According to Cicero (106 BCE-43 BCE), the suppression efforts included military actions, and the entire exercise may have lasted five years. The cult was eventually reduced to a manageable level and subjected to stringent rules, rather than being entirely eradicated. Livius claims that the state took such action because of the festival's frenzied rites, sexual violence, depravity, murder, and revolutionary counterculture, which have been questioned by certain modern researchers.

Photo: https://random-times.com/

Photo: https://dinosaursandbarbarians.com/