Top 10 Interesting Facts About The Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae was regarded as part of the second Persian invasion of Greece between alliances of Greek city-states commanded by King Leonidas and ... read more...the Persian Empire of Xerxes I. This second invasion was a delayed response to Persian loss at the Battle of Marathon by Athenian forces in 490 BC, and it was part of Persian ambitions to expand their empire into the tumultuous world of Ancient Greece. Here are the 10 interesting facts about the Battle of Thermopylae.

-

The political beginnings of the Battle of Thermopylae can be traced back to Xerxes' predecessor, Darius I (the Great), who dispatched heralds to Greek cities in 491 BCE with the goal of convincing them to accept Persian sovereignty. The proud Greeks were so angry that the Athenians threw the Persian heralds into a pit, while the Spartans followed suit and threw them into a well. As part of Darius' initial strategy, Xerxes invaded Greece in 480 BCE. He began in the same manner as his predecessor: he dispatched heralds to Greek cities, but he bypassed Athens and Sparta due to their previous reactions.

Many Greek city-states either sided with Xerxes or remained neutral, while Athens and Sparta spearheaded the resistance, supported by a number of other city-states. Before invading, Xerxes begged Spartan King Leonidas to hand over his arms.

However, according to Anirudh (a novelist, writer, SEO expert, and educationist), the main cause of the battle can be related to the Ionian revolt. The Greeks of the region revolted in what is known as the Ionian Revolt in 499 BC. The Greek city-states of Athens and Eretria backed the Ionian Revolt, during which the Greeks burned down parts of the territory, including Persian temples in the cities.

In 499–494 BC, the city-states of Athens and Eretria aided the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt against Darius I's Persian Empire. The Persian Empire was still young and prone to rebellions among its subjects. Darius, on the other hand, was a usurper who had spent a significant amount of time suppressing revolts against his power.

The Ionian insurrection challenged his empire's unity, so Darius swore to punish anyone implicated, particularly the Athenians, "since he was certain that [the Ionians] would not go unpunished for their rebellion." Darius saw an opportunity to expand his kingdom into the tumultuous environment of Ancient Greece as well. In 492 BC, a preparatory invasion led by Mardonius secured the areas bordering Greece, reconquered Thrace, and forced Macedon to become a client kingdom of Persia.

sutori.com

about-history.com -

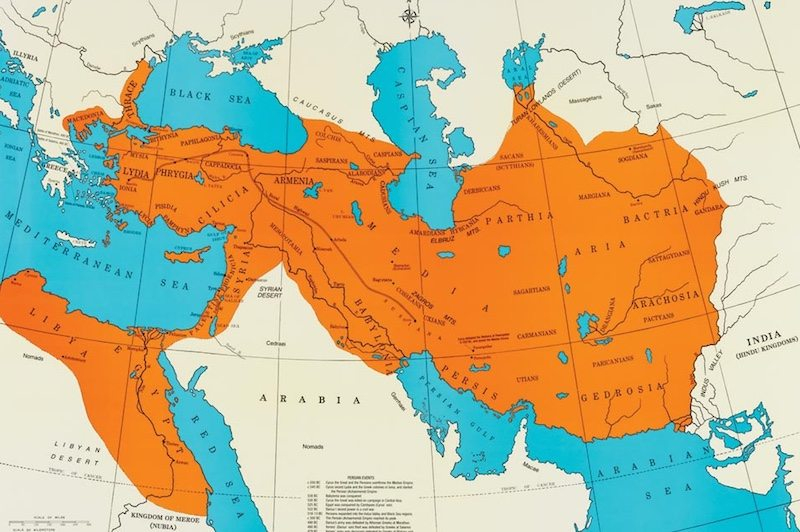

The Achaemenid Empire, also known as the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire located in Western Asia that was founded in 550 BC by Cyrus the Great. Its greatest extent was during Xerxes I, who conquered the majority of northern and central ancient Greece. The Achaemenid Empire spanned from the Balkans and Eastern Europe in the west to the Indus Valley in the east at its peak. The Persian Empire was the largest in ancient times. The empire was greater than any other in history, spanning 5.5 million square kilometers (2.1 million square miles).

Nomadic Persians established the Achaemenid Empire. The Persians were an Iranian people who came to what is now Iran around 1000 BC and settled with the local Elamites in a territory that included northwestern Iran, the Zagros Mountains, and Persis. In the western Iranian Plateau, the Persians were initially nomadic pastoralists. The Achaemenid Empire was not the first Iranian empire; the Medes, another group of Iranian peoples, may have founded a short-lived empire when they played a crucial role in the Assyrians' defeat. Cyrus ascended from this region and defeated the Median Empire, of which he had previously been king, as well as Lydia and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, before formally establishing the Achaemenid Empire.

The Achaemenid Empire is known for imposing a successful model of centralized, bureaucratic administration through the use of satraps; its multicultural policy; the construction of infrastructures such as roads and a postal system; the use of an official language across its territories; and the development of civil services, including the possession of a large, professional army. The empire's prosperity influenced the use of similar systems in subsequent civilizations.

Xerxes I, Old Persian Khshayarsha, byname Xerxes the Great, Persian king (486-465 BCE), the son and successor of Darius I (born c. 519 BCE-died 465, Persepolis, Iran). He is primarily remembered for his major invasion of Greece from across the Hellespont (480 BCE), which included the battles of Thermopylae, Salamis, and Plataea. His ultimate defeat signaled the beginning of the Achaemenian Empire's downfall.

gohighbrow.com

thecollector.com -

One of the most interesting facts about the Battle of Thermopylae is that the Persian army was one of the largest and most sophisticated invading armies ever formed in the ancient world. The number of troops assembled by Xerxes for his second invasion of Greece has been the topic of unending debate, particularly between ancient sources, which record very huge numbers, and modern academics, who estimate considerably smaller proportions. According to Herodotus, there was 2.6 million military personnel in total, along with an equal number of support people. The poet Simonides, who lived at the time, speaks about four million; Ctesias gives 800,000 as the overall number of Xerxes' army.

Modern researchers prefer to dismiss Herodotus' and other ancient authors' statistics as unrealistic, the consequence of victors' miscalculations or exaggerations. These estimations are typically derived from research into the Persians' logistical capabilities at the time, the sustainability of their different bases of operations, and the general manpower restrictions influencing them. Whatever the true numbers were, it is evident that Xerxes was eager to assure the expedition's success by amassing an overwhelming numerical advantage on land and water. As a result, the number of Persian troops present at Thermopylae is as unknown as the entire invading force. It is unknown, for example, whether the entire Persian army marched to Thermopylae or whether Xerxes left garrisons in Macedon and Thessaly.

ludwigheinrichdyck.wordpress.com

the-past.com -

Themistocles was an Athenian statesman and naval strategist whose emphasis on naval force and military talents proved useful during the Persian wars. He was the architect of Athenian sea strength and the primary liberator of Greece from Persian rule at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE.

Plutarch portrays Themistocles as "the man most instrumental in accomplishing the salvation of Greece" from the Persian danger, and he can still be regarded as such. As a statesman and naval strategist, Themistocles planned the Greek defense against the Persians. His naval strategies would also have a long-term impact on Athens, as maritime dominance became the foundation of the Athenian Empire and the golden period.

Thucydides described Themistocles as a man who demonstrated the most undeniable marks of brilliance; indeed, in this particular, he had an amazing and unequaled claim on our adoration.

Many other Greek leaders recognized what was about to happen, and in the autumn of 481, they convened in Corinth to plan for the war against the invaders. At this point, Themistocles persuaded the Athenians that they needed to prepare for the departure of their city. The navy was dispatched to two locations: Artemisium and Salamis. Themistocles proposed the decree.

Themistocles was in command of the Greek naval force at Artemisium during the Battle of Thermopylae when he received word that the Persians had taken the pass at Thermopylae. Because the Greek defense strategy necessitated the holding of both Thermopylae and Artemisium, the decision was taken to withdraw to the island of Salamis. The Persians conquered Boeotia and then seized Athens, which had been evacuated. In late 480 BC, the Greek fleet, seeking a decisive victory over the Persian armada, attacked and defeated the invading force at the Battle of Salamis. Wary of being stuck in Europe, Xerxes withdrew much of his army to Asia, reportedly losing many of his troops to starvation and disease, and leaving behind the Persian military commander Mardonius to continue the Achaemenid Empire's Greek campaign. However, the next year, at the Battle of Plataea, a Greek army decisively defeated Mardonius and his forces, effectively ending the second Persian invasion.

historycollection.com

pixels.com · In stock -

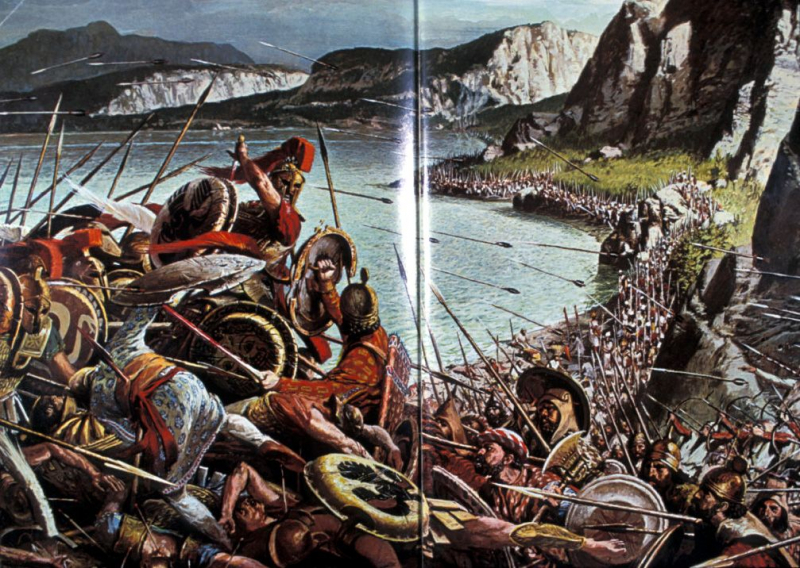

Thermopylae was a gateway region, a pass -three passes- on the main road connecting northern and central Greece. Thermopylae is a tapering plain that extends east to west for about 3 1/2 miles. To the south are mountains, while to the north lies the sea, known as the Gulf of Malis. Thermopylae is narrowest at its two ends, known as the East and West Gates, while the mountains are sharpest in the middle of the pass, known as the Middle Gate. The Greeks defended the pass from here, at the Middle Gate. They took their stand between the precipitous cliffs and the sea, using a crumbling ancient wall that they repaired. In 480 B.C., the land was just about twenty yards wide. The mountains were impenetrable, as far as the Greek defenders knew.

From a strategic standpoint, the Greeks were making the best use of their forces by defending Thermopylae. They had no need to pursue a decisive fight as long as they could prevent a further Persian march into Greece and could thus remain on the defensive. Furthermore, by defending two constrained passageways (Thermopylae and Artemisium), the Greeks' inferior numbers were reduced. The Persians, on the other hand, could not stay in one spot for long due to the difficulty of supplying such a massive force. As a result, the Persians were forced to retreat or advance, with the latter requiring forcing the pass of Thermopylae.

Tactically, the Thermopylae was suitable for the Greek method of battle. A hoplite phalanx could easily block the small pass, without fear of being outflanked by cavalry. Furthermore, the phalanx would have been extremely difficult to assault in the pass for the comparatively poorly armed Persian troops. The Greeks' main vulnerability was the mountain track that ran parallel to Thermopylae and could allow their position to be outflanked. Although unfavorable for cavalry, this route could readily be taken by Persian infantry (many of whom were versed in mountain warfare). Locals from Trachis informed Leonidas of this path, and he stationed a contingent of Phocian warriors there.

Therefore, choosing Thermopylae as a battlefield was a great strategy to defend against the Persian invasion. The Thermopylae pass was barely 200 yards wide at the time, thus the Persians had to come through it in tiny numbers, which could be resisted by the relatively small Greek force. Themistocles realized that the Persian navy could sail across the Straits of Artemisium and surround the Greek ground force. To block the strait, he stationed an allied Greek navy, of which he was captain.

en.wikipedia.org

sjoerdtegelaers.com -

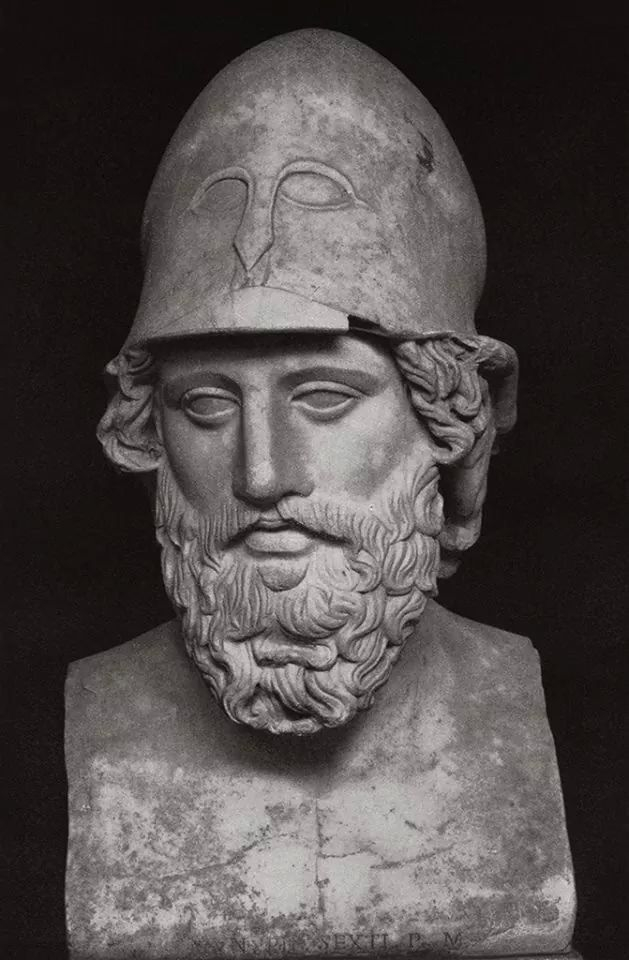

Leonidas I was the 17th king of Sparta and the 17th of the Agiad line, a dynasty descended from the mythological demigods Heracles and Cadmus. Leonidas I was King Anaxandridas II's son. In around 489 BC, he succeeded his half-brother King Cleomenes I on the throne. King Leotychidas was his co-ruler. His son, King Pleistarchus, succeeded him.

Leonidas played an important role in the Second Greco-Persian War. Spartan King Leonidas lead the Greeks in the Battle of Thermopylae while attempting to defend the pass from the invading Persian army; he perished at the battle and became known as the leader of the 300 Spartans. While the Greeks lost this fight, the Persian invaders were driven out the following year.

Sparta consulted the Oracle at Delphi after receiving a request from the confederated Greek soldiers to assist in defending Greece against the Persian invasion. Leonidas marched out of Sparta with a small force of 1,200 men (900 helots and 300 Spartan hoplites) to meet Xerxes' army at Thermopylae, where he was reinforced by forces from other Greek city-states who threw themselves under his command to form an army of 7,000 men.

Whatever the reason for Sparta's participation of only 300 Spartiates (supported by their attendants and perhaps perioikoi auxiliaries), the total force mustered for the defense of Thermopylae's pass was between four and seven thousand Greeks. They were up against a Persian army led by Xerxes I, who had invaded Greece from the north. According to Herodotus, this army had almost two million troops; current academics consider this to be an exaggeration, with estimates ranging from 70,000 to 300,000.

Xerxes waited four days before attacking in the hope that the Greeks would scatter. Finally, on the fifth day, the Persians launched an attack. For the fifth and sixth days, Leonidas and the Greeks repelled the Persians' frontal assaults, killing around 10,000 enemy men. The Persian elite unit known as "the Immortals" was defeated, and two of Xerxes' brothers (Abrocomes and Hyperanthes) were killed in battle. On the seventh day (August 11), a Malian Greek traitor named Ephialtes led the Persian general Hydarnes to the Greeks' rear via a mountain trail. Leonidas then dispatched all Greek troops and remained with his 300 Spartans, 900 helots, 400 Thebans, and 700 Thespians. The Thespians stayed totally of their own volition, vowing not to desert Leonidas and his troops.

According to Herodotus, Leonidas sent away the remaining his warriors out of concern for their safety. The King would have thought it prudent to save those Greek forces for future battles against the Persians, but he knew the Spartans would never quit their position on the battlefield. The men that remained behind were supposed to protect their escape from the Persian cavalry. Except for the 400 Thebans, who surrendered to Xerxes without a fight, the little Greek force was attacked from both sides. After driving back the Persians four times, the Spartans recovered Leonidas' body.

discovermagazine.com

historyextra.com -

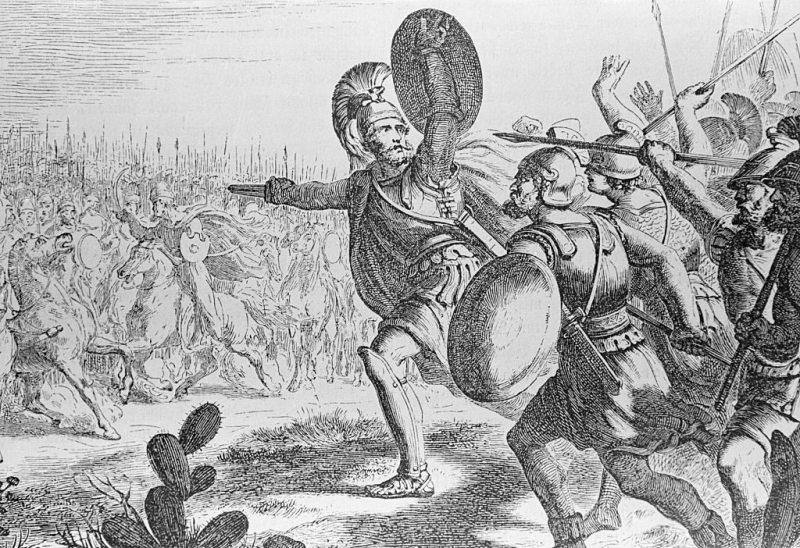

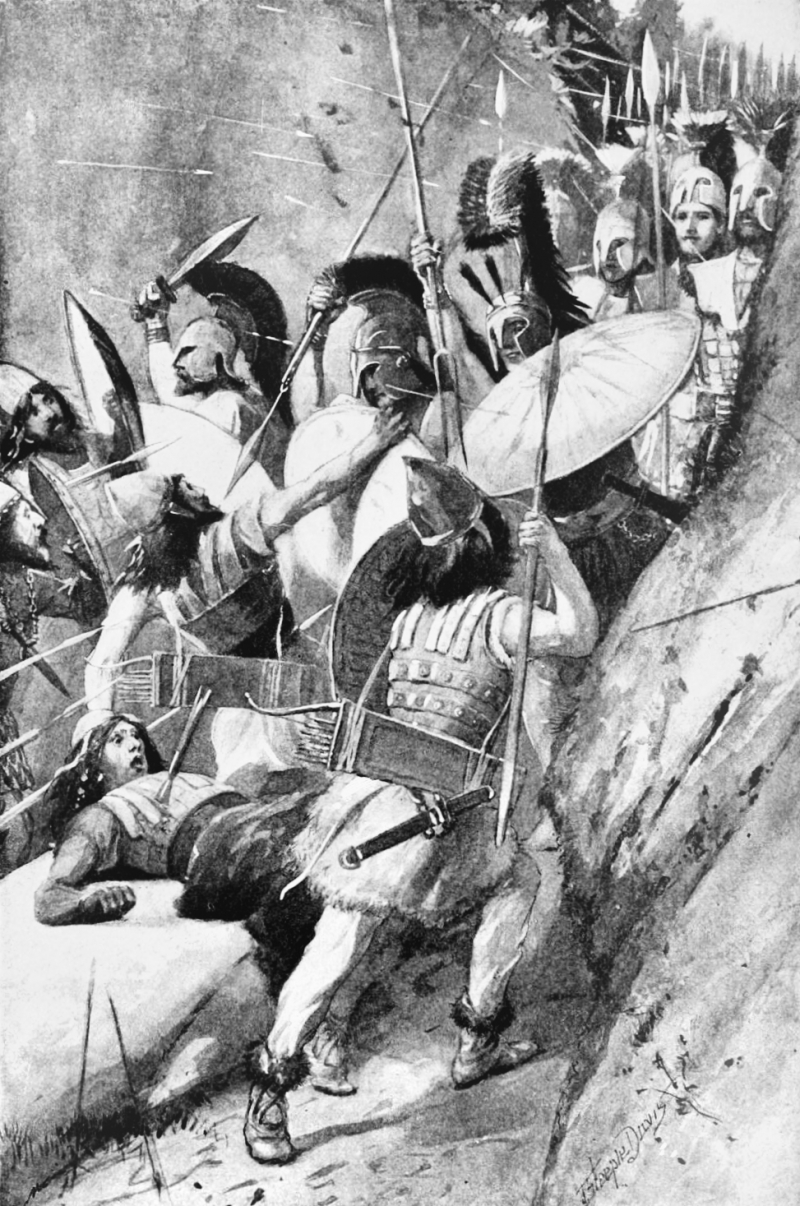

One of the most interesting facts about the Battle of Thermopylae is that the Persians made no progress in the first two days of the battle. Xerxes eventually decided to fight the Greeks on the fifth day after the Persians arrived at Thermopylae and the first day of the conflict. First, he sent 5,000 archers to launch a barrage of arrows, but they were ineffectual because they were fired from at least 100 yards away. Following that, Xerxes dispatched a force of 10,000 Medes and Cissians to capture the defenders and bring them before him. The Persians quickly began a frontal assault on the Greek position in waves of roughly 10,000 troops. The Greeks fought in front of the Phocian wall, at the narrowest part of the pass, with a few warriors as possible.

The Greeks were "superior in valor and in the large size of their shields," according to Diodorus, and "the men stood shoulder to shoulder." This is most likely the classic Greek phalanx, in which the troops built a wall of overlapping shields with layered spear points sticking out from the sides of the shields, which would have been extremely effective as long as it spanned the width of the pass. The Persians' weaker shields and shorter spears and swords prohibited them from attacking the Greek hoplites successfully. According to Herodotus, each city's soldiers were maintained together; units were rotated in and out of the combat to prevent exhaustion, implying that the Greeks had more men than necessary to block the pass. The Greeks killed so many Medes that Xerxes is supposed to have risen up three times while viewing the combat from his seat. The initial wave was "cut to ribbons," according to Ctesias, with just two or three Spartans killed in return.

According to Herodotus and Diodorus, the monarch, having assessed the adversary, threw his strongest warriors, the Immortals, an elite corps of 10,000 men, into a second assault the same day. The Immortals, on the other hand, fared no better than the Medes and made no ground against the Greeks. The Spartans supposedly utilized a strategy of pretending to escape and then turning around and slaughtering the enemy troops who chased them down.

On the second day, Xerxes sent in the soldiers to attack the pass, supposing that their opponents, who were small in number, were now handicapped by wounds and could no longer resist. The Persians, on the other hand, had no more success on the second day than they did on the first. Finally, Xerxes called a halt to the assault and returned to his camp, very confused.

Later that day, while the Persian king contemplated his next move, he received a windfall: a Trachinian named Ephialtes informed him about the mountain path around Thermopylae and offered to direct the Persian army. Ephialtes' motivation was a desire for a prize. That evening, Xerxes dispatched his general Hydarnes and the Immortals under his command to encircle the Greeks via the path. He did not, however, say who those men were. Because the Immortals had been bloodied on the first day, it is conceivable that Hydarnes was given overall command of an enlarged force that included what remained of the Immortals; according to Diodorus, Hydarnes had a force of 20,000 for the operation. The path led from the Persian camp to the east along the ridge of Mt. Anopaea, behind the cliffs that surrounded the pass. It split, with one way descending to Phocis and the other down to the Malian Gulf at Alpenus, Locris' initial town.

youtube.com

historyhit.com -

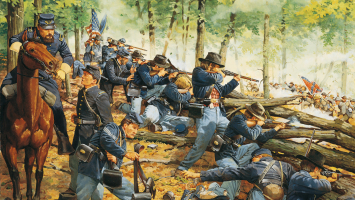

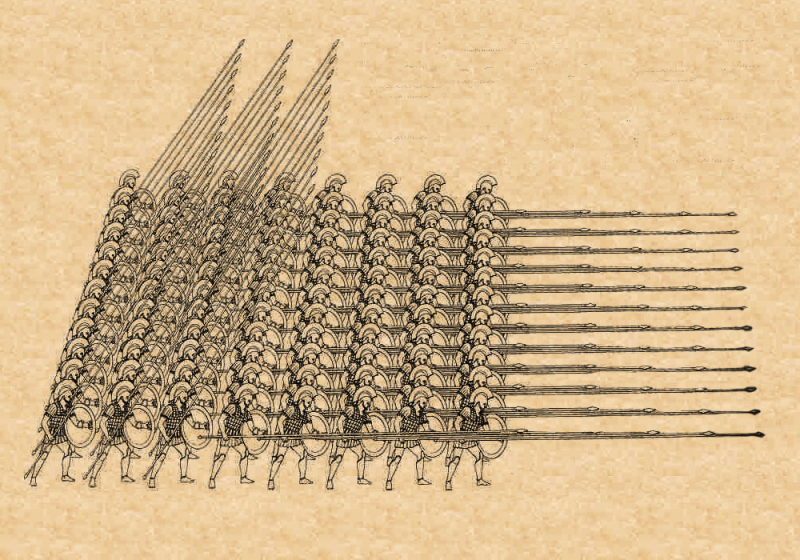

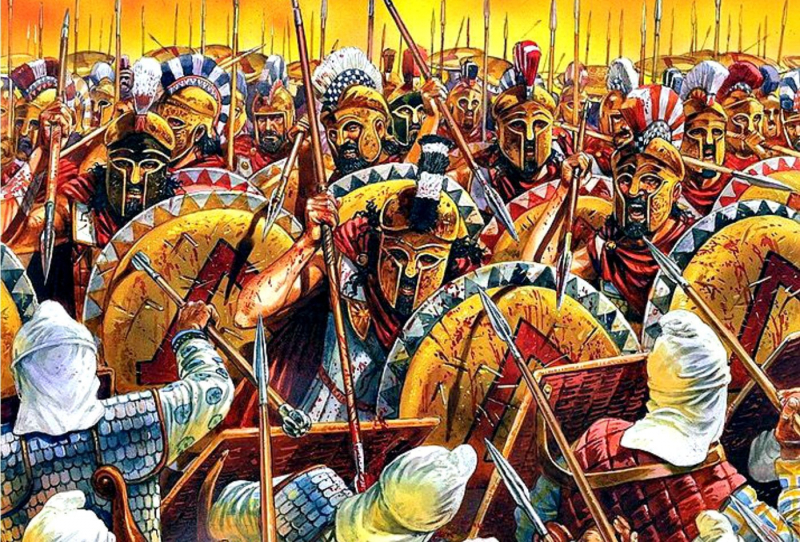

One of the most interesting facts about the Battle of Thermopylae is that the Greek's famous Phalanx formation is used in the battle. A phalanx is a tactical configuration in military science that consists of a block of heavily armed men standing shoulder to shoulder in files many ranks deep. Many spear-armed warriors have historically battled in phalanx-like formations. It was fully perfected by the ancient Greeks and survived in modified form into the gunpowder era, and it is now regarded as the start of European military evolution.

The phalanx was a rectangular mass military formation made up of heavy soldiers armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or other pole weapons. The phrase is most commonly used to characterize the employment of this configuration in Ancient Greek warfare, but it was also employed by ancient Greek writers to denote any massed infantry formation, regardless of equipment. The phalanx may be deployed for combat, on the march, or even camped in Greek writings, representing the mass of men or cavalry that would deploy in line during battle. They marched forward as a unified front.

The Greeks favored heavily armored hoplites at the Battle of Thermopylae, organized in a densely packed formation known as the phalanx, with each man carrying a massive round bronze shield and fighting at close quarters with spears and swords. At close quarters, the larger spears, heavier swords, better armor, and rigorous discipline of the phalanx formation meant that the Greek hoplites would have all of the advantages, and the Persians would struggle to make their greatly superior numbers count in the confined constraints of the terrain.

The Greek tactic of feigning a disorganized retreat and then turning on the enemy in the phalanx formation also worked well on the first day, reducing the threat from Persian arrows, and the hoplites may have surprised the Persians with their disciplined mobility, a benefit of being a professionally trained army. The second day followed the same pattern as the first, and the Greek forces maintained control of the pass. However, an unscrupulous traitor was about to swing the scales in the invaders' favor.

battle-of-thermopylae-jbh.weebly.com

mettlesomegenius.net -

Leonidas was not surprised by the Persians' actions. He was brought up to date on their every action, obtaining news of the Persian outflanking maneuver before first light. Leonidas convened a council before dawn after learning that the Phocians had not held. Some Greeks pushed for evacuation in the face of the overwhelming Persian advance, while others vowed to stay. Following the council, several Greek forces chose to withdraw. Herodotus claimed Leonidas granted their departure with an order, but he also presented an alternative explanation: the retreating army left without orders. 300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, and 400 Thebans were the only soldiers left to guard their retreat. Thus, the Greek last stand at Thermopylae had perhaps 1400 soldiers rather than 300 as stated.

The Spartans had vowed to battle to the death, while the Thebans were being imprisoned against their will. A force of roughly 700 Thespians, led by general Demophilus, the son of Diadromes, refused to leave with the other Greeks and joined the Spartans. The Spartans were ostensibly honoring their promise and the Delphic oracle. It could, however, have been a premeditated strategy to delay the Persian approach and hide the retreat of the Greek army. In truth, with the Persians so close, the decision to stand and the battle was most likely a tactical necessity, one made more appealing by the oracle. The importance of the Thespians' refusal to depart should not be underestimated.

The Greeks sallied forth from the wall this time, hoping to slay as many as they could in the wider part of the pass. They fought with spears until all of them were shattered, then turned to xiphoi (short swords). Abrocomes and Hyperanthes, two of Xerxes' brothers, were killed in this battle, according to Herodotus. Leonidas was also killed in the attack. The Greeks withdrew and took a position on a small hill behind the wall after receiving word that Ephialtes and the Immortals were approaching. The Thebans, led by Leontiades, raised their hands, although a few were slaughtered before the surrender was acknowledged. Some of the last Greeks fought with their hands and teeth. Xerxes surrounded the hill by tearing down a part of the wall, and the Persians poured down arrows until the last Greek was killed.

After losing tens of thousands of men in the first two days of the fight, Xerxes received a lucky break when a Greek named Ephialtes informed him of a mountain route that would carry his army behind the Greek army. With the aim of gaining a prize from the Persians, Ephialtes betrayed his homeland. In the Greek language, his name came to imply "nightmare." Leonidas was aware of the mountain route and had deployed 1,000 Phocians to guard it, but they withdrew wrongly believing that their homeland Phocis was under attack. When Leonidas saw he was being outflanked, he dismissed the majority of the Greek troops.

en.wikipedia.org

pinterest.com -

Thermopylae is undoubtedly the most renowned battle in European ancient history, and it has been mentioned numerous times in ancient, modern, and contemporary culture. At least in Western culture, the Greeks are praised for their military prowess. However, in the context of the Persian invasion, Thermopylae was unquestionably a Greek defeat. The Greek strategy appears to have been to hold off the Persians at Thermopylae and Artemisium; whatever they intended, it was presumably not to yield all of Boeotia and Attica to the Persians. Despite being vastly outnumbered, the Greek position at Thermopylae was practically impregnable.

After their defeat at Thermopylae, the Greeks withdrew from the simultaneous naval Battle of Artemisium. Xerxes went proceeded to burn Greek cities to the ground, despite the fact that most of the population were evacuated. Even though the Persians won the Battle of Thermopylae, they were unable to conquer Greece. The Persians were decisively beaten in the naval Battle of Salamis in late 480 BC, followed by the ground Battle of Plataea in 479 BC, effectively ending the Second Persian Invasion of Greece.

Some argue that Thermopylae was a Pyrrhic triumph for the Persians (i.e., one in which the victor is as damaged by the battle as the defeated party). However, Herodotus makes no mention of the Persian army being affected in this way. The theory ignores the fact that the Persians would seize the majority of Greece in the aftermath of Thermopylae, and that they were still fighting in Greece a year later. Alternatively, some argue that the last stand at Thermopylae was a successful delaying operation that allowed the Greek navy to prepare for the Battle of Salamis. However, when compared to the expected duration (about one month) between Thermopylae and Salamis, the time purchased was insignificant. Furthermore, this theory ignores the fact that a Greek ship was fighting at Artemisium during the Battle of Thermopylae, inflicting losses.

defenceredefined.com.cy

nationalgeographic.co.uk