Top 9 Marvelous Types of Ancient Chinese Art

One of the longest ongoing traditions in the world is undoubtedly ancient Chinese art. Neolithic art, which dates back to 10,000 BC, is when most rudimentary ... read more...ceramics and sculptures were produced. Religion, politics, and philosophy have all had a significant influence on the development of ancient Chinese art as it has changed over time. This encompasses the arts of calligraphy, poetry, and painting, each of which had its own distinctive features depending on the dynasty. Without further ado, here are the top types of traditional Chinese art.

-

Peking opera (jng jù) is regarded as one of China's national treasures, combining excellent singing, beautiful gymnastics, lavish multicolored costumes, and passionate storytelling to produce a theatrical experience unlike any other. Peking opera was immensely popular during the Qing period and is still practiced as an art form in China today.

Peking opera can be scary to a newcomer. However, after you get past the painted faces, the performance itself reveals stories from Chinese history that have been passed down for thousands of years.

Farewell My Concubine (bà wáng bié j), a traditional Peking opera that depicts the tragic narrative of King Shang Yu and his loving Consort Yu from the late Qin dynasty, is one such example.

Due to its failure to appeal to a modern audience, Peking opera has seen a loss in viewers in the modern period. In addition, becoming a great performer in the Peking opera requires many years of difficult training beginning at a young age.

But outside of China, the art genre is experiencing a revival. Western audiences have shown interest in Chinese troupes that travel abroad. Even Western admirers have traveled to China to study the craft while competing and performing in well-known talent competitions on CCTV.

Chinese music - Jingxi (Peking opera) - Britannica CCTV春晚's Channel -

In several regions of China, shadow puppetry, also known as shadow play, was particularly common during the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties. Shadow puppets were initially created out of paper mâché and later were manufactured from donkey or ox leather. Their Chinese name, pi ying, which translates to "shadows of leather," is a result.

A beloved concubine of Wu Emperor of the Han Dynasty passed away from illness more than 2,000 years ago; the emperor mourned her so much that he lost the drive to rule. One day, a preacher just so happened to notice kids playing with dolls where the floor had vivid shadows. The astute minister was inspired by this incident and came up with a plan. He painted the concubine's cotton puppet after making it. He invited the emperor to see a puppet show behind a curtain as darkness fell. The emperor was ecstatic and began to enjoy it. The official history book claims that this tale is where shadow puppetry first appeared.

Politics and shadow puppetry were intertwined. For instance, this folk craft was so well-liked in Beijing during the reign of Emperor Kangxi that there were eight lavishly compensated puppeteers in one prince's palace. To make up for their inability to enjoy local amusement due to linguistic limitations, the Manchu rulers brought the puppet performance with them when they stretched their dominion to different regions of China. In order to stop the peasant insurrection from spreading during the period of 1796 to 1800, the government outlawed the public performance of puppet performances. The popularity of shadow puppet shows did not start to grow until 1821. The show is currently in danger of dying out, just like other traditional art forms like Nuo Drama.

Shadow puppetry captures an audience's attention with its lingering music, superb sculpture, brisk color, and energetic performance.

One voice speaks thousands of years of history; a pair of hands controls millions of warriors. This is how a shadow puppeteer operates. A shadow puppet group is made up of five people and is known as the business of the five. One person controls the puppets, one person plays a horn, a suo-na horn, and a yu-kin, one person plays the banhu fiddle, one person controls the percussion instruments, and one person sings. This singer takes on all of the roles in the puppet performance, which is obviously incredibly challenging. Not only that, but the vocalist also performs with over 20 different musical instruments in a puppet performance. This traditional folk art is enhanced by these archaic musical instruments.

The shadows of flat puppets are projected onto a white cloth screen that serves as the play's stage. Shadow puppets resemble paper cuts in appearance, but they may be manipulated more freely because their joints are connected by a thread. The audience is drawn in despite the scene's simplicity and primitiveness by the flawless performance. For instance, with the help of the operator, a puppet can smoke and breathe out a smoke ring. In one scene, the maid's actions are reflected in the mirror while she sits there. Each of the five puppets being played by the operator has three threads. 15 threads are held in ten fingers. It makes sense why the operator is compared to the Kwan-yin with 1000 hands.

Shadow puppets use exaggeration and dramatic dramatization to overcome the limitation caused by only seeing the profile of the puppets. Puppets' features and costumes are colorful and amusing. The floral color, beautiful sculpting, and smooth lines elevate the puppets beyond mere props to works of art. A figure requires up to 24 operations and over 3,000 cuts.

All of the figures have a broad head and a narrow, tapering torso. A man has a large head, a square face, a wide forehead, a tall, powerful frame that is not overly macho. A woman has a slim figure without being excessively lean, a small mouth, and a narrow face. For Chinese women, effeminacy and compassion are the norm. Generals with combat gear conjure up images of bravery and prowess, while scholars have a beautiful bearing and wear lengthy robes.

The figures are designed in accordance with traditional moral judgment and aesthetics. The mask of a figure might reveal his persona to the audience. A red mask, like the masks in Beijing Opera, denotes uprightness, a black mask, integrity, and a white mask, deceit. The positive figure features long, narrow eyes, a tiny mouth, and a straight nasal bridge, whereas the negative form has small eyes, a projecting forehead, and a sagging mouth. Even before performing any act, the clown has a circle around his eyes, giving a hilarious and frivolous attitude.

Shadow play includes opulent background elements like furniture, architecture, vessels, and lucky patterns. The play, being earthy art, leaves an impression on viewers with its vividness and sophistication. A framed puppet can make a unique and enjoyable keepsake.

The shadow puppets also feature historical and folkloric figures such as the Monkey King, Emperor Qin Shi Huang, or the four ancient beauties, Xi Shi, Wang Zhaojun, Diao Chan, and Yang Guifei, in addition to the characters required for a particular production. The most prevalent form of shadow puppetry is thought to be in Shaanxi. In Xi'an, the Academy Gate Cultural Street is the best spot to buy shadow puppets as gifts. Here, you can choose from hundreds of figures in various sizes and positions, each of which reveals a unique world.

Chinese Shadow Play, Chinese Shadow Shows, Chinese Shadow Puppetry - Easy Tour China UNESCO's channel -

Calligraphy, meaning "beautiful writing," has been recognized as an art form in many different cultures around the world, but its importance in Chinese culture is unparalleled. Calligraphy was considered the ultimate visual art form in China from a very early date, valued more than painting and sculpture, and rated alongside poetry as a source of self-expression and cultivation. In fact, how one wrote was just as essential as what one wrote. It is important to take into account a number of aspects in order to comprehend how calligraphy came to hold such a significant position, including the materials used in calligraphy, the characteristics of the Chinese written alphabet, and the value placed on writing and literacy in traditional China.

Brush, ink, paper, and inkstone are some of the supplies used in calligraphy. Although archaeological evidence suggests that brushes were used in China far earlier, their widespread use began during the Han dynasty. A common brush is made out of a bundle of animal hairs (black rabbit hair, white goat hair, and yellow weasel hair were all popular) squeezed within a bamboo or wood tube (though jade, porcelain, and other materials were also occasionally used). The hairs are not all the same length; rather, an inner core is surrounded by shorter hairs, which are covered by an outer layer that tapers to a point. Brushes come in a range of forms and sizes, which define the style of the line produced. But the one thing these brushes all share is adaptability. More than any other characteristic, this one enables the calligraphic line to be so expressive and flexible.

Calligraphy ink is typically formed from lampblack, a sooty residue produced by burning pine resin or oil behind a hood. The lampblack is collected, mixed with adhesive, and then pressed into molds. The solidified cakes or sticks can then be ground against a stone and combined with water, allowing the calligrapher to adjust the thickness of the ink and color density. Ink cakes and ink sticks themselves eventually became decorative art forms, with many well-known artists creating designs and patterns for their molds.

One of China's most significant contributions to the world of technology is the invention of paper, which is widely recognized. Although recent tomb discoveries show that paper was known at least a century earlier, tradition attributes the creation of the method to Cai Lun in 105 C.E. Paper served as an accessible substitute for silk as a base material for calligraphy and painting. Paper was created from a variety of fibers, including mulberry, hemp, and bamboo.

Brush, ink, and paper, along with the inkstone (a carved stone slab with a reservoir for grinding ink and mixing it with water), are regarded in China as the Four Treasures of the Study (wenfang sibao), emphasizing the great regard with which calligraphy materials are held. These Four Treasures are made using the same materials as traditional Chinese painters. Some critics have pointed to this as a reason why calligraphy is more revered in China than abroad.

It is helpful to think about the qualities that were prized when calligraphy started to emerge as an art form separate from mere writing; that is, when examples of handwriting started to be valued, collected, and treated as art, in order to understand how calligraphy came to occupy such a prominent position in China. One of the oldest known occurrences is the Han emperor Ming of the first century, who sent a messenger to retrieve a fragment of his cousin's writing before he died away after learning that he was near death. By doing this, Emperor Ming hoped to preserve the calligraphic vestiges of his relative's individuality, enabling him to "commune" with him even after his death.

More than any other element, the assertion that calligraphy may be used as a medium of revelation and self-expression explains why it has been so highly valued. A brief examination of how calligraphic skill is mastered may offer some light on why such expressive potential was perceived to be inherent in calligraphy in the first place.

The written characters in Chinese are composed of thousands of distinct graphs. Each consists of a constant set of strokes that are carried out in a specific order. These very severe limitations produce one of the truly distinctive qualities of calligraphy: the viewer is able to mentally recreate, stroke by stroke, the precise steps by which the work was created. Additionally, the observer may see incredibly minute details of execution, such as whether a stroke was performed quickly or slowly or with great delicacy or force, etc.

yoyochinese.com Chinese Calligraphy Demo - Colorado State University International Programs's Channel -

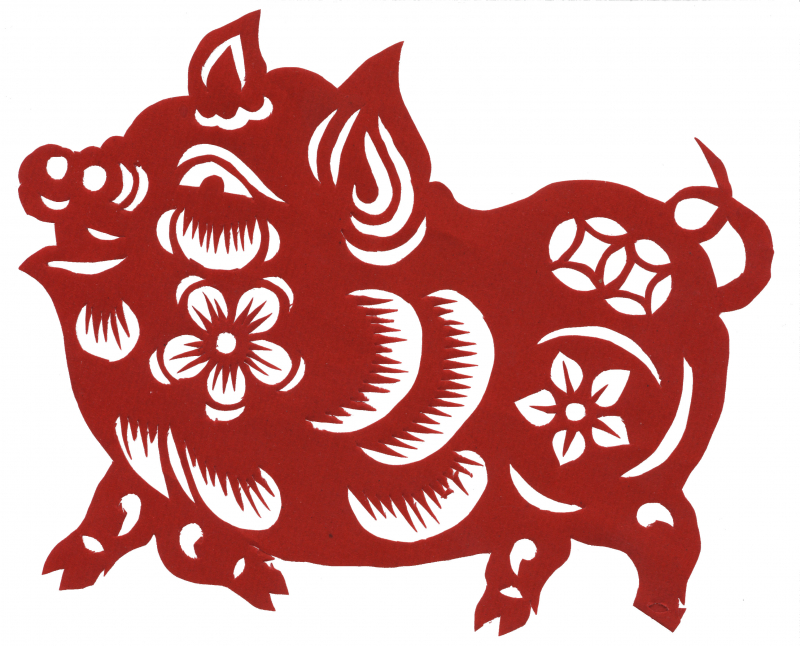

Chinese paper cutting, a peculiar form of visual art that is uniquely Chinese, has existed for centuries - possibly even longer than the paper itself! Chinese paper-cutting was added to the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009. Simple patterns ranging from portraits to animal zodiacs can be made using just a piece of paper, generally a red one, and a pair of scissors.

Chinese paper cut-outs are well-liked decorations used to adorn windows and mirrors due to their affordability and craftsmanship. Inside, an amazing pattern is made when light filters through the cut-outs' negative gaps. A Chinese New Year custom is to decorate windows with paper cuts; these attractive cut-outs are referred to as "window flowers" or (chuāng huā) in Chinese.

A symmetrical circle from the sixth century unearthed in Xinjiang, China, is the earliest surviving paper cutout. The craft of Chinese paper cutting is thought to have begun in China after Ts'ai Lun invented paper in 105 CE. Long before the paper was produced, however, there are accounts of the Chinese carving hollowed patterns into other thin materials such as leaves, silver or gold foil, silk, and leather. People were already cutting tree leaves into various art forms and handing them out as gifts throughout the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046 - 771 BC)!

There is also a lovely folklore about the origins of the first paper-cut: Emperor Wu adored his wife, Concubine Li, during the Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220 CE) of ancient China. He couldn't eat or sleep well after her death because he missed her so much. He yearned to see her again. To meet the Emperor's request, one of the ministers cut out the figure of Concubine Li from linen and placed it up against the tent's low candlelight. Emperor Wu observed the silhouette of his beloved wife from a separate tent and assumed her spirit had returned. The ministers urged the Emperor not to approach the tent lest Concubine Li's soul vanish in order to conceal the falsehood. He composed a sonnet as the shadow vanished to express his sorrow.

As paper became more inexpensive, the art gained favor among the general public and evolved into a traditional handicraft for rural women. Every female was expected to master the profession, and brides were frequently judged based on their abilities. During the Southern Song Dynasty (1127 - 1279 CE), craftspeople, mostly men, made a living by cutting paper. Some were experts at cutting Chinese characters, while others were experts at cutting flowers and other designs. Craftsmen in Jizhou, Jiangxi Province, began pasting paper-cut works on ceramics before glazing and baking them in the kiln to produce colorful designs on the ceramics.

The Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) Dynasties saw the height of paper-cutting art. Almost anything may be decorated with them, including embroidered fabrics, fans, and folk lanterns. The Running Horse Lantern, also known as (zǒu mǎ dēng), was a well-known ornate lantern from the Ming Dynasty. A candle was surrounded by cardboard cutouts of generals riding horses, which rotated as hot air rose from the candle. On the lamp's screen, the cutouts' shadows created the appearance of galloping horses pursuing one another. Then, the designs of the lantern changed to include images of gods and people.

Chinese characters are also widely utilized in traditional paper-cut designs. Some popular characters include ‘福 (fú)’ which denotes blessing, and ‘喜 (xǐ)’ which indicates happiness. It is worth noting that the character ‘喜’ is almost always cut as ‘囍’ and used to symbolize double the happiness during weddings! The Chinese characters frequently contain meanings that symbolize average people's life goals.

Chinese paper cutting - Wikimedia Commons GBTIMES's Channel -

Chinese artists used a variety of media and different painting styles. The most common formats were on walls (from approximately 1100 BCE), coffins and boxes (from approximately 800 BCE), screens (from approximately 100 CE), silk scrolls that could be held in the hand or hung on walls (from approximately 100 CE for horizontal and from approximately 600 CE for vertical hanging), fixed fans (from approximately 1100 CE), book covers (from approximately 1100 CE), and folding fans (from c. 1450 CE).

The first artists used wood and bamboo as their primary materials, but these were soon replaced by plastered walls (about 1200 BCE), silk (around 300 BCE), and paper (from c. 100 CE). Canvas would not be commonly utilized until the eighth century CE. Animal hair was cut to a tapering end and fastened to a bamboo or wood handle to make brushes. They were, interestingly, the identical tools employed by the calligrapher. The inks were created by rubbing a dried cake of animal or vegetable materials mixed with minerals and glue on a damp stone. Because there was no commercial production of inks, each artist had to laboriously make their own.

Landscapes and portraits were the two most common subjects for Chinese paintings. Beginning in the Warring States Period (5th–3rd century BCE), portraits in Chinese art were traditionally created with great restraint because the subject was typically a great scholar, monk, or court official who should, by definition, have a good moral character and deserve to be depicted with respect. Because of this, faces frequently have a blank appearance with only a tiny trace of expression or character displayed. In portraits of emperors and Buddhist dignitaries, in particular, the character of the subject is frequently much more vividly represented in their stance and interaction with other persons in the painting.

There were, however, instances of more realistic portraits, which can be observed especially in tomb wall paintings. Painting historical characters in educational moments from their lives that demonstrated the rewards of moral behavior was one area of portraiture. Naturally, there were other paintings depicting individuals with less lofty goals, such as the popular images of Chinese family life set in a garden.

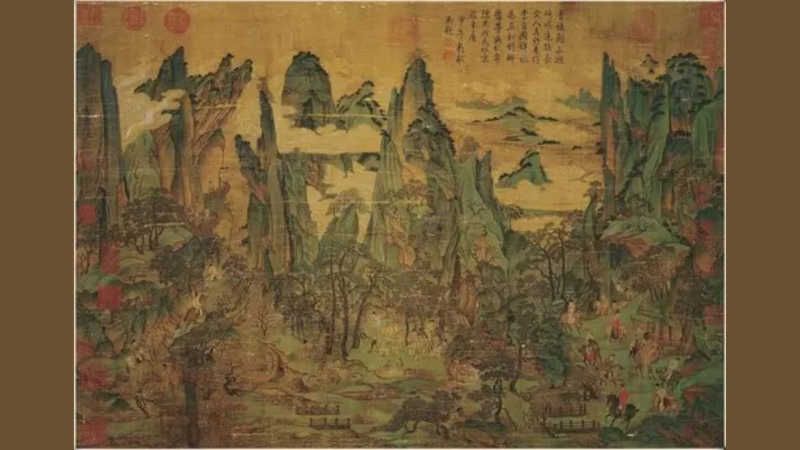

As long as there have been artists, there have been landscape painters, but the genre really took off during the Tang dynasty when artists started to become much more interested in the place of mankind in nature. In Tang paintings, little human figures frequently lead the audience across a broad landscape of mountains and rivers. It shouldn't come as a surprise that mountains and water are prevalent in landscape paintings because the Chinese word for landscape directly translates to "mountain and water." The scene typically depicts a specific season of the year and includes rocks and trees as well. The use of color was limited; either everything was painted in different tones of a single color (illustrating calligraphy's origins) or two colors were blended, most frequently blues and greens.

According to the Taoist concept of the benefits of studying quiet nature, agricultural laborers are rarely shown in landscape paintings, and no precise place is supposed to be depicted. Later periods, on the other hand, would witness more intimate and abstract depictions of nature, focusing on highly specialized themes like bamboo gardens. From the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), detailed paintings of a single animal, flower, or bird were very popular, but they were viewed as aesthetically inferior to the other categories of Chinese painting.

Nonetheless, particular animals became symbolic of certain concepts and appeared in paintings, as they did in other art forms such as bronze work. A pair of mandarin ducks, for example, represented a happy marriage, a deer represented money, and fish represented fertility and abundance. Plants, flowers, and trees all have their own significance. Bamboo grows straight and true, much like a good scholar should, pine and cypress signify endurance, peaches represent long life, and each season has its own flower: peony, lotus, chrysanthemum, and prunus.

Depth was produced in paintings by incorporating mist or a lake in the center area, creating the illusion that the mountains were further behind. Other techniques include painting more distant items with softer ink and fainter strokes, while front objects are made darker and more realistic. Another prominent feature of Chinese art is the use of numerous angles and perspectives to depict a situation. The 8th century CE painted silk panorama known as 'The Emperor Ming Huang Traveling in Shu' is one of the most famous of all Chinese landscape paintings. It is a sweeping and intricate mountain panorama masterpiece in the traditional Tang style, employing only blues and greens.

Han Women, Dahuting Tomb. - Unknown Artist (Public Domain)

The Emperor Ming Huang Travelling in Shu - Unknown Artist (Public Domain) -

The art of large-scale figure sculpture has not endured well, although some magnificent specimens still exist, such as those carved out of the rock face at the Longmen Caves and Fengxian temple close to Luoyang. The 17.4 m tall statues, which date to 675 CE, depict a Buddhist Heavenly King and demon guardians. The life-sized sculptures of Shi Huangti's "Terracotta Army" are another well-known example of Chinese art. The tomb of the Qin emperor was guarded by almost 7,000 warrior figurines, 600 horses, and many chariots. Despite all of the figures being created from a small selection of assembled body parts made from molds, great effort was made to make each one distinctive. Faces and hair, in particular, were altered to give the appearance of a real army made up of unique individuals.

The Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) is renowned for its cast bronze artwork in terms of smaller-scale pieces. Three-legged cauldrons, often with legs shaped like animals, birds, or dragons, are typical forms of bronze pots. They might have handles and lids and come in square or circular shapes. Masks, scroll designs, and repetitive patterns are some examples of sharp relief decorations. Additionally, the Shang craftsmen created vessels that resembled three-dimensional animals, including rams, elephants, and mythical creatures.

Small-scale sculpture of the Han period took the form of stone or bricks stamped and carved with relief scenes, and it was especially frequent in tombs. Outstanding examples can be found at Jiaxiang's Wu Liang Shrine. There are approximately 70 relief slabs dating to 151 CE or 168 CE that depict battle scenes and notable historical people like Confucius, all recognized by accompanying texts and providing a chronological Chinese history in a graphic record similar to a history book.

Cast bronze statues of horses were also common throughout the Han era. These are frequently shown at full gallop with just one hoof resting on the base, giving the impression that they are virtually flying. From the Han era, it is common to find earthenware figurines of solitary standing women, men, and servants. Small sculptures and elaborate incense burners were made from cast bronze. These were frequently gilded or inlaid with gold and silver. A magnificent example is a late 2nd century BCE kneeling servant girl-shaped oil lamp made of gilded metal.

Large figure statues were occasionally erected outside the tombs of emperors and other notable individuals, although many later sculptures focused on Buddhist themes. By the Tang dynasty, the Buddhist monasteries' affluence had allowed for a significant increase in the production of sacred art. The Buddha and the bodhisattvas continued to be the most popular subjects, and they were depicted in everything from tiny figurines to life-size monuments. Figures, in contrast to earlier periods, became far less static, and their apparent fluid movement even drew criticism from some who thought that, on occasion, serious religious figures now resembled court dancers.

Emperor Qin Shi Huang's Terracotta Army to Be Exhibited at EXPO 2017 - The Astana Times

Buddhism in the Tang (618–906) and Song (960–1279) Dynasties - Education - Asian Art Museum -

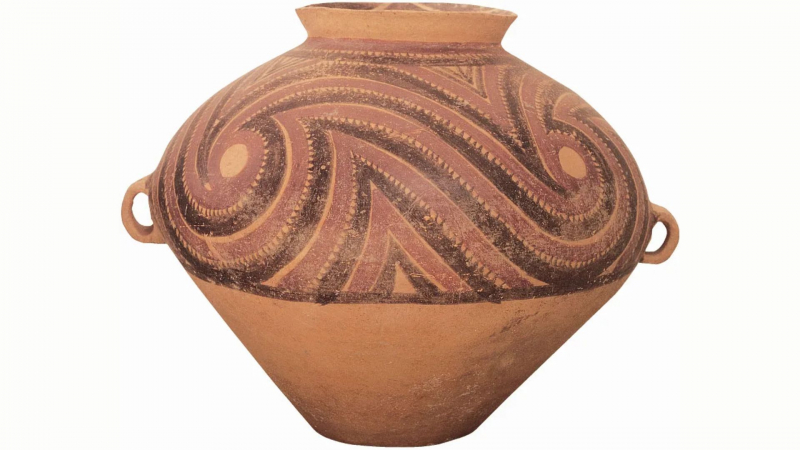

The Chinese were pottery and ceramics masters. They made everything from hefty and useful earthenware storage jars to finely designed porcelain bowls, vases to garden seats, and teapots to pillows. They created the first glaze goods, the first green celadons, and the first cobalt blue underglaze wares. During the Han period, early advancements in techniques and kilns resulted in both greater firing temperatures and the first glazed pottery. Pottery, particularly jars painted with a grey slip prevalent in Han tombs, frequently copied the shape and design of bronze vessels, which would be an aim of many potters in following centuries. Small unglazed clay models of typical homes were created and placed in tombs to accompany the deceased and, presumably, symbolically fulfill their longing for a new dwelling. Many of these models come with a nearby animal pen and figurines of the people and animals that live there.

The technical mastery of Tang potters was higher than that of any of their forebears. Blues, greens, yellows, and brown were among the new color glazes that were invented during this time and were made from cobalt, the iron, and copper. Additionally, colors were blended to create the three-colored goods for which the Tang era is renowned. Tang pottery occasionally had lavish inlays of gold and silver. Even more well-known ceramics with their distinctive and frequently imitated blue-on-white decoration, which itself had taken design cues from previous Chinese paintings, would be created throughout the Yuan (1271-1368) and Ming (1368-1644) dynasties.

Amphora | China | Tang dynasty (618–907) - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Britannica Chinese pottery - Britannica -

Silk is a fine, smooth material made from mulberry silkworm cocoons, which are soft protective shells (insect larvae). According to legend, silkworms were discovered by Lei Tzu, the wife of the Yellow Emperor, who ruled China around 3000 BC. According to one version of the story, while walking through her husband's gardens, she discovered that silkworms had destroyed several mulberry trees. She gathered a number of cocoons and sat down to rest. While she was drinking her tea, one of the cocoons she had collected landed in the hot tea and began to unravel into a fine thread. Lei Tzu discovered she could wrap her fingers with this thread. She then convinced her husband to give her permission to raise silkworms in a grove of mulberry trees. In order to make the cocoon's fibers strong enough to be woven into cloth, she also created a unique reel to draw them out as a single thread. Although it is unclear how much of this is accurate, it is undeniable that silk has been grown in China for many centuries.

Originally, silkworm farming was restricted to women, who were responsible for growing, harvesting, and weaving. Silk quickly became a status symbol, and originally, only royalty were permitted to wear silk clothing. Over time, the rules were gradually relaxed until, during the Qing Dynasty (1644—1911 AD), even peasants, the lowest caste, were permitted to wear silk. Silk was so valuable during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) that it was used as a unit of currency. Government employees were paid in silk, and farmers paid their taxes in grain and silk. The emperor also used silk as diplomatic gifts. Silk has been used to create paper, musical instruments, fishing lines, and bowstrings. The first evidence of silk paper use was found in a nobleman's tomb who is said to have passed away around 168 AD.

The lucrative trade route now known as the Silk Road, which took silk westward and brought gold, silver, and wool to the East, was eventually created by demand for this exotic fabric. The Silk Road was named after its most valuable commodity, which was thought to be more valuable than gold.

The Great Wall of China, the Pamir mountain range, modern-day Afghanistan, and the Middle East were all part of the roughly 6,000-kilometer Silk Road, which began in Eastern China and ended at the Mediterranean Sea. Damascus served as a significant trading hub along the route. The goods were then transported across the Mediterranean Sea from there. Few businesspeople traveled the entire route; instead, most commodities were handled by a network of middlemen.

Because the mulberry silkworm is indigenous to China, the country was the sole producer of silk for hundreds of years. The Byzantine Empire, which ruled over the Mediterranean region of southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East from 330 to 1453 AD, eventually spread the secret of silk-making to the rest of the world. Another legend has it that in 550 AD, monks working for the Byzantine emperor Justinian smuggled silkworm eggs to Constantinople (Istanbul in modern-day Turkey) hidden inside hollow bamboo walking canes. However, the Byzantines were just as secretive as the Chinese, and the weaving and trading of silk fabric was a strict imperial monopoly for many centuries.

The Arabs later conquered Persia in the seventh century, taking their fine silks with them.

As the Arabs swept across these countries, silk manufacture subsequently extended throughout Africa, Sicily, and Spain. In the tenth century, Andalusia in southern Spain served as Europe's primary silk-producing region. But by the thirteenth century, Italy was the continent's top producer and exporter of silk. Venetian traders engaged in substantial silk trading and promoted the relocation of silk cultivators to Italy. Even today, the province of Como in northern Italy is renowned for its silk processing.The European silk industry was destroyed by the nineteenth century and industrialization. One of the many factors driving the trend was cheaper Japanese silk, trade in which was greatly facilitated by the opening of the Suez Canal. Then, in the twentieth century, new manmade fibers like nylon began to be used in what had previously been silk products like stockings and parachutes. The European silk industry was also stifled by the two world wars, which disrupted the supply of raw materials from Japan. After WWII, Japan's silk production was restored, with improved raw silk production and quality. Until the 1970s, Japan was the world's largest producer of raw silk and practically the only major exporter of raw silk. However, China has progressively regained its status as the world's largest producer and exporter of raw silk and silk yarn in more recent decades. Around 125,000 metric tons of silk are produced globally each year, with China accounting for over two-thirds of that total.

Silk in Ancient China: The Legend of Lady Hsi Ling Shih - Lux Magazine The Ancient Library's Channel -

During the early fourteenth to fifteenth centuries in China, foreign influence aided the development of cloisonné. The first securely dated Chinese cloisonné dates from the reign of Ming Xuande (1426–35). Cloisonné, on the other hand, is documented during the previous Yuan dynasty, and it has been suggested that the technique was introduced to China at that time via the western province of Yunnan, which received an influx of Islamic people under Mongol rule. A few cloisonné objects have been stylistically dated to the early Ming dynasty's Yongle reign (1403-24).

The art of cloisonné involves decorating metal objects with colorful glass paste that is encased in copper or bronze wires that have been bent or hammered into the appropriate pattern. The enclosures, often called cloisons (French for "partitions"), are typically glued or soldered to the metal body. Metallic oxide is used to color the glass paste, or enamel, before it is painted into the design's defined spaces. Typically, the vessel is burned at a low temperature of around 800°C. After firing, enamels frequently contract, therefore the process is repeated numerous times to fill in the designs. After this procedure is finished, the vessel's surface is rubbed until the edges of the cloisons are apparent. They are then gilded, frequently on the edges, interior, and base.

Cloisonné objects were primarily intended for use in the decoration of temples and palaces because their flamboyant splendor was thought appropriate for the function of these structures but not well suited to a more restrained atmosphere, such as that of a scholar's home. Cao Zhao (or Cao Mingzhong) expressed this viewpoint in 1388 in his influential Gegu Yaolun (Guide to the Study of Antiquities), in which cloisonné was dismissed as only suitable for lady's chambers. However, by the reign of Emperor Xuande, this ware had become highly valued at court.

Dung-Chen - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Foliated dish with floral srcolls - The Metropolitan Museum of Art