Painting

Chinese artists used a variety of media and different painting styles. The most common formats were on walls (from approximately 1100 BCE), coffins and boxes (from approximately 800 BCE), screens (from approximately 100 CE), silk scrolls that could be held in the hand or hung on walls (from approximately 100 CE for horizontal and from approximately 600 CE for vertical hanging), fixed fans (from approximately 1100 CE), book covers (from approximately 1100 CE), and folding fans (from c. 1450 CE).

The first artists used wood and bamboo as their primary materials, but these were soon replaced by plastered walls (about 1200 BCE), silk (around 300 BCE), and paper (from c. 100 CE). Canvas would not be commonly utilized until the eighth century CE. Animal hair was cut to a tapering end and fastened to a bamboo or wood handle to make brushes. They were, interestingly, the identical tools employed by the calligrapher. The inks were created by rubbing a dried cake of animal or vegetable materials mixed with minerals and glue on a damp stone. Because there was no commercial production of inks, each artist had to laboriously make their own.

Landscapes and portraits were the two most common subjects for Chinese paintings. Beginning in the Warring States Period (5th–3rd century BCE), portraits in Chinese art were traditionally created with great restraint because the subject was typically a great scholar, monk, or court official who should, by definition, have a good moral character and deserve to be depicted with respect. Because of this, faces frequently have a blank appearance with only a tiny trace of expression or character displayed. In portraits of emperors and Buddhist dignitaries, in particular, the character of the subject is frequently much more vividly represented in their stance and interaction with other persons in the painting.

There were, however, instances of more realistic portraits, which can be observed especially in tomb wall paintings. Painting historical characters in educational moments from their lives that demonstrated the rewards of moral behavior was one area of portraiture. Naturally, there were other paintings depicting individuals with less lofty goals, such as the popular images of Chinese family life set in a garden.

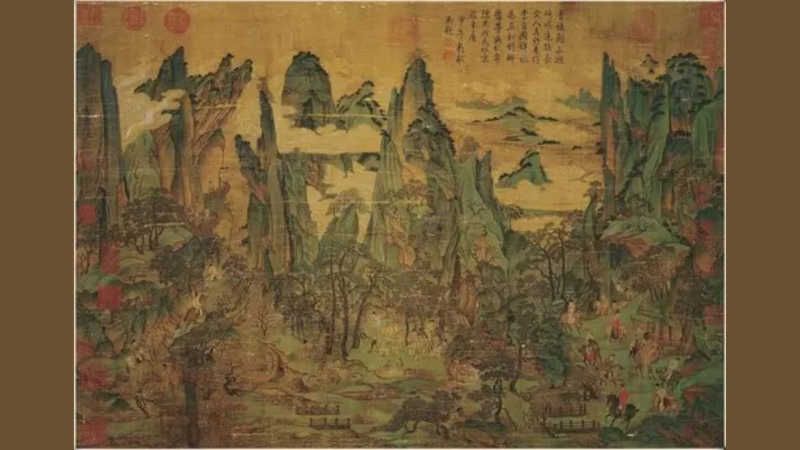

As long as there have been artists, there have been landscape painters, but the genre really took off during the Tang dynasty when artists started to become much more interested in the place of mankind in nature. In Tang paintings, little human figures frequently lead the audience across a broad landscape of mountains and rivers. It shouldn't come as a surprise that mountains and water are prevalent in landscape paintings because the Chinese word for landscape directly translates to "mountain and water." The scene typically depicts a specific season of the year and includes rocks and trees as well. The use of color was limited; either everything was painted in different tones of a single color (illustrating calligraphy's origins) or two colors were blended, most frequently blues and greens.

According to the Taoist concept of the benefits of studying quiet nature, agricultural laborers are rarely shown in landscape paintings, and no precise place is supposed to be depicted. Later periods, on the other hand, would witness more intimate and abstract depictions of nature, focusing on highly specialized themes like bamboo gardens. From the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), detailed paintings of a single animal, flower, or bird were very popular, but they were viewed as aesthetically inferior to the other categories of Chinese painting.

Nonetheless, particular animals became symbolic of certain concepts and appeared in paintings, as they did in other art forms such as bronze work. A pair of mandarin ducks, for example, represented a happy marriage, a deer represented money, and fish represented fertility and abundance. Plants, flowers, and trees all have their own significance. Bamboo grows straight and true, much like a good scholar should, pine and cypress signify endurance, peaches represent long life, and each season has its own flower: peony, lotus, chrysanthemum, and prunus.

Depth was produced in paintings by incorporating mist or a lake in the center area, creating the illusion that the mountains were further behind. Other techniques include painting more distant items with softer ink and fainter strokes, while front objects are made darker and more realistic. Another prominent feature of Chinese art is the use of numerous angles and perspectives to depict a situation. The 8th century CE painted silk panorama known as 'The Emperor Ming Huang Traveling in Shu' is one of the most famous of all Chinese landscape paintings. It is a sweeping and intricate mountain panorama masterpiece in the traditional Tang style, employing only blues and greens.