Top 9 Most Important Battle Tactics of Ancient Romans

Even now, military academies and staff colleges like Sandhurst continue to teach students about Roman military strategy. Military strategies have changed over ... read more...time, but the Romans were mainly responsible for the development of modern technology and strategic military strategies. The Roman military was flexible, and it approached combat very differently from other armed forces. The Romans were unique because of their talent. They modified already-used weaponry and techniques in addition to developing their own, in order to further their own objectives. Their victory on the field of combat is evidence of their creative and tactical approaches, which were not only effective but also efficient. Ever questioned how? They have made the following cutting-edge developments.

-

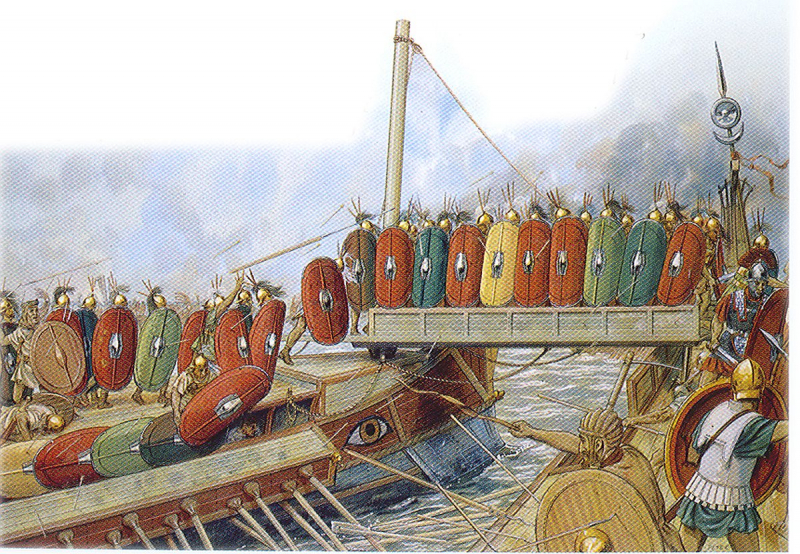

The testudo, which means "tortoise" in Latin, was a Roman shield-wall construction. It was a frontline approach that the legionaries frequently employed during battle. It was a defensive system that permitted Roman foot soldiers to defend themselves against missile attacks and opposing bowmen.

The testudo configuration was not normal, but it was utilized in unique circumstances to manage certain combat hazards. The layout was intricate and difficult to create, requiring the soldiers' skill and synchronicity.

Romans were able to surround opponents with a wall of wood thanks to their very huge scuta shields. The formation's front rank would crouch behind its over one-meter-tall shields that were connected. Shields would be held above the heads of the men in front by the second rank, and so on. Men on the flanks and in the back could likewise present and lock their roughly meter-wide shields together, their sharply curved fronts making an excellent missile barrier, if the all-around defense was required.

Some testudo descriptions distinguish between "heavily-armed" infantry with curved scuta and lighter troops with flat shields, who provide the tortoise's roof.

While a testudo could be marched around, it moved at a tortoise-like pace, and the formation was primarily utilized in response to distant missile fire. It was used in sieges to provide troops and engineers with safe access to the walls they were attempting to destroy before more permanent defensive constructions could be constructed.

In 36 BC, Marc Antony (of later Shakespearean fame) allegedly used the approach against the Parthians, who had some success against the testudo with mounted archers.

Imperium Romanum

THE FEW GOOD MEN -

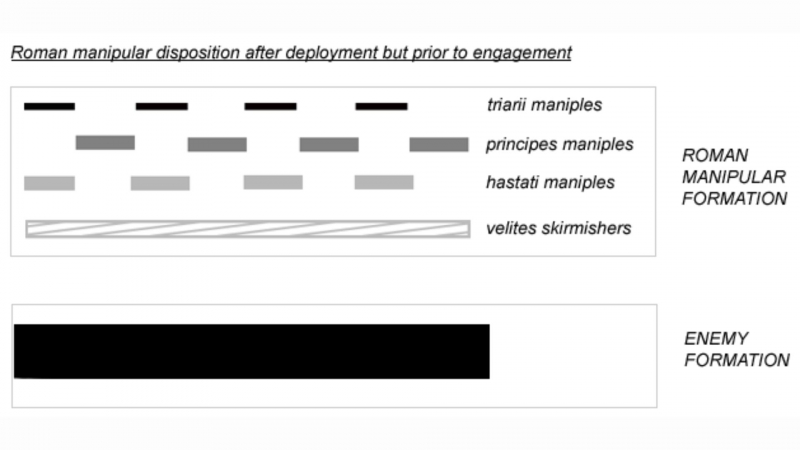

The Romans adopted this phalanx, which was originally Greek. Where a legionary stood in the battle order depended on their level of military seniority. The triple line consisted of the hastate, the principles, and the triarii. Surprisingly, the hastati, the least experienced guys, comprised the front rank. The principles and then the combat veterans, the triarii, were behind them. The unfortunate velites, the newest (and typically least skilled) recruits, stood in front of everyone. They would throw javelins at approaching foes before vanishing behind the triarii.

The line beyond which a Roman legionary would not retreat was the final rank, which might be some distance back. The phrase "falling on the Triarii" came to indicate engaging in a last-ditch battle.

The three lines would frequently create a mile-long battle configuration with alternating gaps, creating a broader but still seemingly unbroken fighting front. These spaces offered the already adaptable legion even more leeway, allowing the rear ranks to advance up into a threatened line.

Travian: Legends Blog

Quora -

The Roman army was the master of formation movement in antiquity, providing the general with a selection of already drilled maneuvers. The legionaries would form a wedge and assault the adversary at the cry of "cuneum formate."

It's a basic issue of physics. A sharp needle pierces enemy soldiers' bodies, as a thickening mass behind them expands to further divide their forces. A human wedge, like a wooden wedge, can split a log and smash an opposing force.

The best troops would be arranged in deep lines at the "tip" of the wedge, concentrating their killing prowess against a weaker adversary. This mismatch of blades or missiles enables the wedge to force a gap against an enemy that is being squeezed into a smaller space, which can then be enlarged by the rest of the formation.

The wedge was frequently utilized. Wedge attacks helped bring Alexander the Great of Macedon's reign to an end at the Battle of Pydna in 168 AD. After blocking a British charge with spear volleys, a massively outnumbered Roman force moved in wedge formations to put an end to Boudicca's epic insurrection in 60 or 61 AD.

History Hit

Flickr -

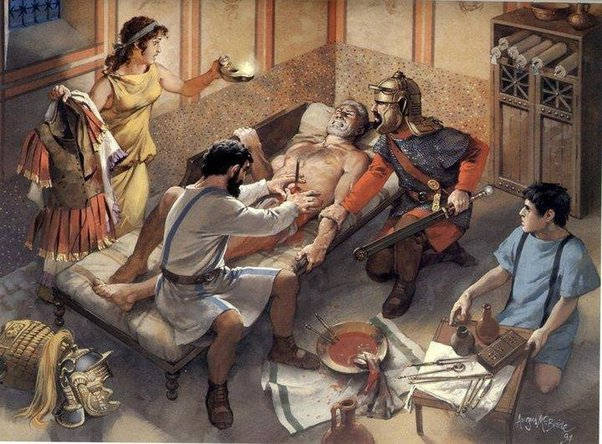

The Romans were renowned for having a well-organized structure that set them apart from their adversaries, yet they nevertheless experienced casualties like everyone else. The Romans had highly skilled professionals at their disposal who were hired to handle casualties and logistics. They were formed up of professionals who collaborated to make the army both physically and strategically strong, including engineers, physicians, and even architects.

Injured soldiers were treated on the battlefield by a dedicated medical unit and a surgery unit in the Roman military. These experts were trained to perform all tasks, including making sure the surgical instruments were clean.

They used to disinfect the tools with hot water before using them, a practice that lasted until the nineteenth century. In addition, they were responsible for the sanitation of army camps in order to prevent the spread of sickness. They also ensured that soldiers ate well, which is possibly why Roman soldiers - or at least those who survived the battlefield - had longer lives than civilians during that time period.

The Roman Army Medical Service - Malton Museum

Quora -

Boarding was the most common technique for attacking the Roman fleet. Because Rome gained dominance through a land force, naval fighting was a difficulty for a long time, and lack of ability frequently resulted in defeats. The solution was the "raven" (Corvus), a boarding ramp with two or one spike (resembling a bird's beak, hence the name). It enabled the use of the infantry force at sea and the tactic of fast jumping to the enemy.

During the First Punic War (264-241 BCE), the ancient Romans encountered larger-scale maritime fighting for the first time. Despite the fact that some ships were built using a captured Carthaginian ship as a model, the Roman's and their allies' method of shipbuilding was very different from that of the Carthaginians. Additionally, Carthage's officers, rowers, and hired mercenaries outperformed the opposition in terms of skill.

A new strategy of warfare had to be created due to the difficult circumstances the Roman maritime fleet was in and its early defeats. The person who first used the boarding bridge is unknown to us. Although the dearth of knowledge regarding the inventor's name shows that the Romans did not want to share the success, Adrian Goldsworthy speculates that it might have been a Sicilian or a youthful Archimedes.

The Latin name Corvus does not exist in ancient texts and was most likely derived from Polybius' Greek name - corax. Corvus was approximately 11 meters long and 1.2 meters wide. On either side, there was a knee-high railing. The deck was joined to a 7-meter-tall column in the center. The platform was rotated using ropes and pulleys, allowing it to be lowered to the left or right side and forward.

The Battle of Cape Mylae in 260 BCE saw the first application of corvus. The Carthaginian commanders ignored the enigmatic constructions emerging on the opposing ships because they had superior navigational abilities, which the plodding, inexperienced Roman fleet lacked. However, as soon as the piers descended, containing a total of thirty Phoenicians, the prevailing Roman naval forces changed the maritime conflict into a land fight, shattering their optimism. According to a number of reports, Carthage was beaten and suffered the loss of 30 to 50 ships.

IMPERIUM ROMANUM

Corvus - Livius -

The Romans invented yet another tactical weapon in the seventh century AD. This contentious weapon was thought to have been invented by Syrian engineer Callinicus, and it used a vicious "liquid fire" that could burn while floating on water.

It utilized a flammable substance emitted by the weapon and was used to set fire to hostile ships. Its most notable attribute was that it ignited when it came into touch with water, which greatly aided the Romans during maritime wars, particularly those undertaken by the Eastern Roman Empire.

However, the method of creating Greek fire remained a well-guarded military secret. A few writers from the time period explain how Greek fire could be effectively fought using sand and potent vinegar.

Greek fire - Wikipedia

Greek City Times -

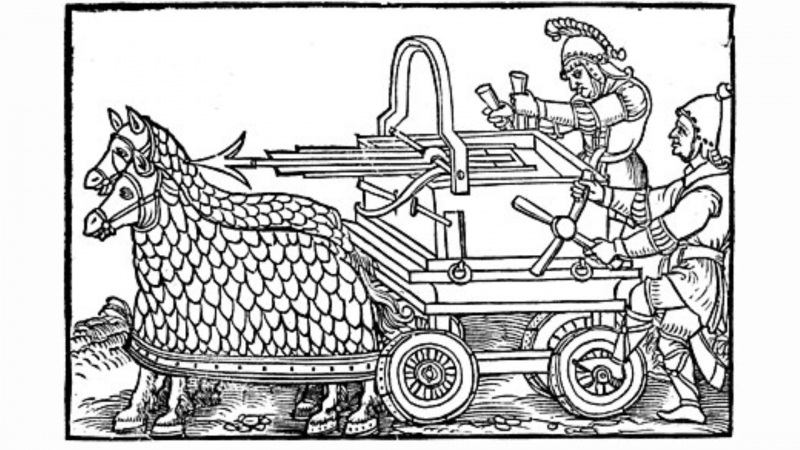

The basic ballista mechanism was created by the Greeks in the fifth century BC, but the Romans surely expanded the practical use of this weapon system for use in combat. The manuballista, a Roman siege engine from the imperial era, served as the foundation for the carroballista. The Roman army used it because it was the most sophisticated two-armed torsion engine. The ability to maneuver was the main distinction between these two systems.

The carroballista was a terrifying hybrid of the Roman ballista and the catapult. For optimum power, it blasted hefty bolts using a system of accumulated spring energy. On the battlefield, two men were required to handle this weapon, and it was quickly adopted as a major piece of Roman artillery. According to current reports, each legion possessed 55 carroballista.

Carroballista - Wikipedia

Ballista - Wikiwand -

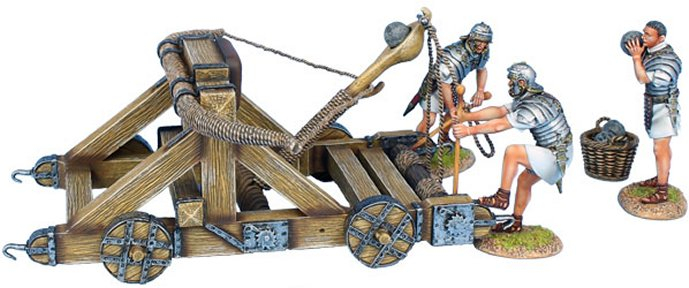

The onager, a form of catapult that used torsional force produced by a twisted rope or springs to generate the potential energy needed for the shot, was named after the wild ass because of its kick. The first person to mention it was the historian Ammianus, who compared the weapon to a scorpion.

In addition to the aforementioned artillery systems that could utilize boulders to damage walls and small fortresses, the Romans also started to use ballistae, which were primarily used for assaulting enemy troops with bolts (as was discussed above). The Romans utilized rocks and flammable substances as projectiles, firing them at their enemies. The Romans won many battles thanks to this military strategy.

Troops of Time

IMPERIUM ROMANUM -

In the Roman Empire, highways were critical for trade. The systematic development of roadways by trained engineers allowed for the flourishing of trade and culture. After the second century, the Romans constructed a large road network.

During the first Roman Empire, 30 military routes flowed out of the capital city, with nearly 400 roads connecting them. The highways facilitated speedier communication and commercial commodities exchange. The Roman legions could now travel around 35 to 40 kilometers per day, which was far faster than before.

Roads were not the only thing built. Along the road, the Romans built homes that allowed the army to create communication networks and communicate intelligence and secret information over large distances.

Roman roads - Wikipedia

History Hit