Top 10 Misconceptions About Ancient Battle Tactics

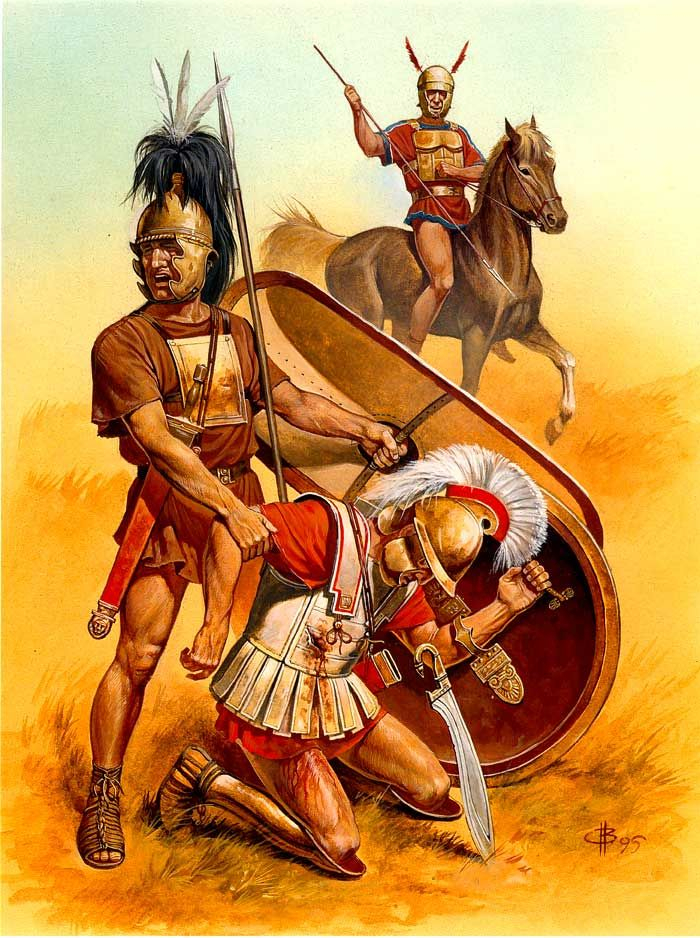

Anyone attempting to imagine battles from a millennium or two ago will have their perception significantly bent by influences that, in turn, were significantly ... read more...shaped by fantasists, such as pulp fiction painter Frank Frazetta. To better understand how far off we are from that reality, let's look at what soldiers in the distant past truly had to look forward to. The past was often (and shockingly) far more commonplace than fiction would have us believe. It was also more terrible.

-

There has never been an arm more revered throughout history than the sword, as the opening quotation and our third entry imply. The club may be more widely used than the most famous blade of monarchs. People are undoubtedly given the impression that an army equipped with long swords would dispatch any line of spearmen in close battle, with the possible exception of a phalanx.

The examination of historical warfare by History.com shows that armies where the soldiers relied on swords were at a significant disadvantage. Even a short sword needs enough of elbow room to be wielded correctly. This is part of the reason why the Roman legion, while engaging their opponents, primarily favoured the short swords known as gladiuses, though even that was largely supported by javelins and slings to pierce opposing lines. In conclusion, unit cohesion in ancient warfare defeated even the most sophisticated individualized weapon.

The author of the fantasy book A Tale of Magic Gone Wrong, in which a character carries a spearspade, is Dustin Koski. He wants to dispel the myth that they were actual antiquated weaponry one day.

https://www.denix.co.uk/

https://oriental-arms.com -

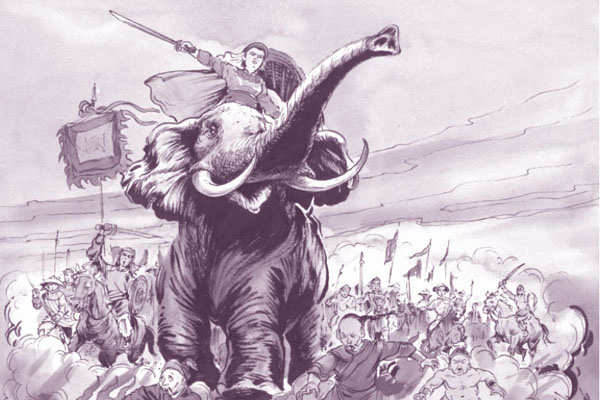

Internet commentators will emerge from hiding every time a historical drama depicts a lady using a sword in combat to call it ridiculous. It is assumed that men and women just function at fundamentally different levels of strength. Even fantasy shows like The Witcher received harsh criticism for their innovative choices.

The typical response is to name specific historical examples of female warriors, such as Queen Boudica or Queen Tomyris. But that strategy is inherently wrong because it suggests that these troops were the outliers who proved the rule.

Instead, let's think about the armies where the use of female combatants was not even worth mentioning. Two such examples are Trung Trac and Trung Nhi of Vietnam, who not only oversaw the drive of the Chinese out of Vietnam in 40 AD, but also served as the instructors for a general staff of 36 other women. Or there were the numerous Celtic burial sites from the Iron Age, which also contained chariots and female bones.

Insufficient armies when this was still a common practice? Hopefully, the reports of East Africa, where regiments of female archers from Western Sudan or comparably sizable formations of female warriors from Ghana were still being pitted against European forces during the Middle Ages, would suffice to make the point.

https://www.vietvisiontravel.com/

https://taucaotoc.vn/ -

It makes sense to suppose that you'll want something as hefty as a sledgehammer if a sword is going to be expected to slash at opponents who are wearing armor and holding shields. By the time the Medieval age arrived and warriors needed a weapon to disable individuals wearing the greatest deflectors available, warhammers had become a common tool.

Swords have really historically been quite lightweight. According to Escapist magazine, heavier broadswords were probably only going to weigh around four and a half pounds, so if a person can easily hold a typical laptop, they are likely in good enough shape to hold a sword.

Even the Middle European Zweihander, which is known to have been among the most biggest swords ever used in actual battle, weighed 8.8 pounds. A musket used in the American Civil War weighed around 9.75 pounds, therefore soldiers who attempted to bayonet or club their adversaries were exerting more effort than the most powerful ancient swordsmen.

https://oriental-arms.com

https://www.pinterest.com/ -

One of the long-held theories about the American Revolution was that the country gained freedom because, despite their inability to beat His Majesty's forces in open warfare, the Americans could use guerrilla warfare to gain the upper hand. Although we've previously discussed how accurate that is, history textbooks frequently portray the idea that American rebels preferred guerrilla tactics as some sort of innovation. Practical arguments support the notion that this was the case: Fielding an army would not have been feasible due to less advanced agricultural technologies because both sides would have needed to send men home for the harvests or risk financial collapse.

However, battle and attrition were concepts that were well known even in ancient times. Emperor Fabius was known for his prowess with them, and as a result, the colloquial expression "Fabian tactics"—being strategically aggressive to wear down an adversary, especially one who is typically unbeatable in a pitched battle—came to be used. While he decimated their troops four times on the Italian Peninsula during the Second Punic War, they would enable Rome to overcome Hannibal. During the Gallic Wars, they came dangerously close to stopping Julius Caesar, and Caesar gave Vercingetorix a lot of credit for his expertise in handling them.

According to Garrett Fagan and Matthew Trundle's New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare, even Sparta was defeated through attrition warfare, in large part due to its extreme reliance on slave labor, which made their positions more precarious if the troops had to be mustered for an extended period of time. Any amount of toughness won't be able to support troops who can't get supplies or don't seem to be moving forward.

http://historycollection.co

http://justtimepass-lifeisbeautiful.blogspot.com -

You are aware of the appearance of an Imperial Roman soldier. Leather armour in the form of a type of skirt, and a red tunic. It makes natural that the empire would want a uniform piece of apparel to foster a sense of community among its legion. The Roman Empire often frequently couldn't be bothered to make the effort, unless according to papers that have survived.

Payroll records reveal that soldiers' salary was actually deducted for wearing uniforms, thus the less fortunate troops decided against trying it. There are numerous letters from the time period in which the troops request clothing from their own homes, including one famous letter in which a struggling soldier stationed in Britain asked his family to give him wool socks.

The myth that all Romans dressed the same was largely a product of Hollywood. In Technicolor, those vivid red uniforms looked wonderful. In retrospect, the idea that red was an expensive dye used only by nobility at the time seems kind of ridiculous. Imagine if all soldiers in the present-day were shown as donning Louis Vuitton or Gucci outfits before heading into battle.

https://www.pinterest.com/

https://paintingvalley.com/ -

It would make sense for ancient ships to frequently ram one another because wooden ships would naturally appear to be much more vulnerable to it than metal ones. With arrows or any other heavy equipment most ancient vessels could deploy in battle, it is quite difficult to sink an enemy ship. An extraordinarily literal example of backfiring is when an attacker uses fire, as this might cause the attacker's own ship to catch fire.

However, it has been repeatedly noted, for example in Raffaele D'Amato's 2017 book Imperial Roman Ships, that no captain would do it if they could avoid it. Even with a successful ramming, the attacker's hull, mast, or other structural components could all be compromised. Furthermore, even if a ship managed to destroy an adversary with a single hit, there was still a chance that the rammer would be trapped and perish along with the sinking ship. This is why even much ricketier ships, like those in Constantine's navy in the fourth century AD, were frequently more successful due to their greater speed and maneuverability.

This also applied to naval combat in Ancient Asia. The Korean navy was reluctant to ram enemy ships with their innovative ironclad ships because it was too risky, even though they were praised for being unsinkable. Modern fleets, where ships have interchangeable mass-produced parts, and the capacity to sink ships make boarding a vessel for capture considerably riskier than in the past, if anything, making ramming ships more likely.

http://bet-ilim.blogspot.com/

http://www.militaryheritage.com -

The concept that post-traumatic stress disorder wasn't truly identified or documented until the 20th Century is frequently disseminated in history classrooms. The general opinion is that World War I, which marked the beginning of that age, was only written off as "shell shock." People are presumed to have been trained with sterner material than they can muster now because life away from the battlefield was so much tougher than modern conveniences. Because they believed that civilization was softening up their soldiers, even Ancient Romans occasionally credited barbarian soldiers with being more resilient.

Even while they may not have used the term "post-traumatic stress disorder," ancient historians did note the impacts. The famed historian Herodotus, who chronicled the Greco-Persian Wars, identified spear-carrier Epizelus as having psychological issues after the war had concluded. According to a PBS documentary from hundreds of years ago, Assyrian tablets documented the psychological suffering that soldiers had experienced as a result of their time in the military.

Although Huangdi's Canon of Medicine, written around 200 BC, makes no direct references to the term in Ancient China, it strongly alludes to soldiers who experience suspiciously comparable psychological disorders. The research suggests that having less technology does not always result in super-soldiers.

http://nigerianobservernews.com/

https://www.newsweek.com/ -

Diomedes, a character in the ancient Greek novel The Iliad, is struck by an arrow and declares that archery is only appropriate for cowards. According to Peter Gainsford, this contributed to the idea that this point of view was held by the majority of Greeks rather than just one injured individual. The way that the phalanx, a close-quarters formation, came to be so revered for its alleged invincibility served as more evidence for this notion. As a result, you may now witness representations of the Greeks, such as in the graphic novel 300 and the movie 300, where Spartan King Leonidas expressly states this.

In truth, archers were frequently used as a tactic of suppression during maneuvers, even by the Spartans, the supposedly best phalanx combatants. To be fair, researchers have discovered tributes to archers in ancient Sparta proper, though there are no records of Spartan archers decimating foes the way Welsh bowmen or Mongol horse archers are known to have done. They didn't require proof of this as heroic archers are frequently honored in Greek mythology and epics like Homer's Odyssey.

https://talesoftimesforgotten.com/

https://www.pinterest.fr/ -

Perhaps only communities that valued the military would endure in ancient times because nations were frequently at war. Without ideas like martial honor to drive them, especially in periods when there were few money benefits available, how were soldiers supposed to be inspired to risk their lives in battle?

So it must be with Ancient China, as it overcame such a sizable and powerful empire. This is a particularly widespread misconception in the West, which typically associates Ancient China with military films like Mulan, Red Cliff, or The Wall by John Woo.

Confucius, the most famous counsel China has ever produced, was known for his contempt for warriors and belief that victories in war weakened the authority of a king. An old Chinese proverb states that "good men do not become soldiers." Much harsher than the more modern American proverb "Mamas, don't let your sons grow up to be cowboys" Sun Tzu's Art of War was enticing because, by emphasizing cunning above honorable battle, it avoided the destruction of vital resources and infrastructure.

https://www.worldhistory.org/

https://www.entrepreneur.com/ -

A civilization is always seen as an abnormally huge rabble of savages until it gains enough power to be called a "empire." How often have people witnessed Roman armies charging towards the legions like schoolkids on the last day of school while facing off against mud-caked mobs and untidy fur piles? This is a particularly useful perspective when nationalists want to assert that the Roman military's heavy reliance on barbarian troops in its final several centuries was the cause of its demise.

A detailed examination of the historical evidence refutes this. In his own candor, Julius Caesar admitted that the well organized Gauls he fought for eight years were a formidable opponent. Their social structures, armor, and weapons all showed they possessed an extremely well-organized infrastructure. More to the point, specialized barbarian cavalry archers outnumbered Roman cavalrymen roughly three to one in some of the greatest Roman victories, as the one at Strasbourg in 356 AD.

At Alesia, the battle he won against the greatest odds of his career, even Caesar heavily relied on mounted German mercenaries to defend his army. The evidence suggests that, if barbarian mercenaries were responsible for Rome's demise, they had also played a significant role in its growth.

https://en.europe-israel.org

https://www.quora.com/