Top 5 Most Important Historical Figures In Colombia

Colombia is a country steeped in history. Everywhere you go in Colombia, you'll see statues of famous figures and streets named after important people, and ... read more...every time you pay for something, there's a good chance you'll use a bill or coin with a famous Colombian on it. Today, in the list, we'd like to introduce you to some of the most important historical figures in Colombia.

-

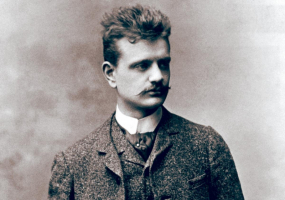

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 - 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led the independence of what are now Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia from the Spanish Empire. He is also known as El Libertador, or the Liberator of America. He is regarded as one of the most important historical figures in Colombia.

Simón Bolívar was born into a wealthy creole family in Caracas, Captaincy General of Venezuela. He lost both parents before the age of ten and moved around a lot. Bolivar was educated abroad and lived in Spain, as was common for upper-class men at the time. He was introduced to Enlightenment philosophy and met his future wife Mara Teresa Rodrguez del Toro y Alaysa while living in Madrid from 1800 to 1802. Del Toro died of yellow fever after returning to Venezuela in 1803. Bolívar embarked on a grand tour that ended in Rome, where he vowed to end Spanish rule in the Americas. In 1807, Bolívar returned to Venezuela and proposed to other wealthy Creoles that Venezuela gain independence. When Napoleon's Peninsular War weakened Spanish authority in the Americas, Bolívar became a zealous combatant and politician in the Spanish American wars of independence.

In 1810, Bolívar began his military career as a militia officer in the Venezuelan War of Independence, fighting for the first and second Venezuelan republics, as well as the United Provinces of New Granada, against Spanish and more native Royalist forces. Following the capture of New Granada by Spanish forces in 1815, Bolívar was forced into exile in the Republic of Haiti, led by Haitian revolutionary Alexandre Pétion. Bolivar befriended Pétion and received military support from Haiti after promising to abolish slavery in South America. Returning to Venezuela, he established a third republic in 1817 before crossing the Andes to liberate New Granada in 1819. In New Granada in 1819, Venezuela and Panama in 1821, Ecuador in 1822, Peru in 1824, and Bolivia in 1825, Bolivar and his allies defeated the Spanish. Venezuela, New Granada, Ecuador, and Panama merged to form the Republic of Colombia (Gran Colombia), with Bolívar serving as president in Peru and Bolivia.

In his final years, Bolívar became increasingly disillusioned with and estranged from the South American republics due to his centralist ideology. He was removed from office one by one until, following a failed assassination attempt, he resigned the presidency of Colombia and died of tuberculosis in 1830. He is regarded as a national and cultural icon throughout Latin America; the countries of Bolivia and Venezuela, as well as their currencies, bear his name. His legacy is diverse and far-reaching, both within and beyond Latin America, and he has been memorialized all over the world through public art, street names, and popular culture.

commons.wikimedia.org

simple.wikipedia.org -

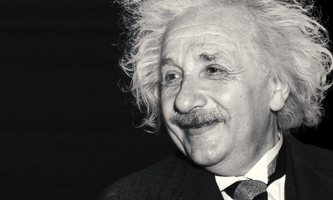

Policarpa Salavarrieta, also known as La Pola, was a Neogranadine seamstress who spied for the Revolutionary Forces during the Spanish Reconquista of the Viceroyalty of New Granada. She was apprehended by Spanish Royalists and executed for high treason. The Colombian Woman Day is observed on the anniversary of her death. She is now regarded as a Colombian independence heroine and among the most important historical figures in Colombia.

Policarpa was not involved in politics prior to 1810, but by the time she returned to Bogotá in 1817, she was actively participating in political issues. Because Bogotá was a Reconquista stronghold where the majority of the population supported Pablo Morillo's takeover, it was extremely difficult to enter and exit the city. Policarpa and her brother Bibiano entered the capital with forged documents and safeguards, as well as a letter of introduction written by two Revolutionary leaders, Ambrosio Almeyda and José Rodrguez; they recommended that she and her brother stay in the house of Andrea Ricaurte y Lozano under the guise of working as her servants. In reality, Andrea Ricaurte's house was the epicenter of the capital's intelligence gathering and resistance.

Policarpa was regarded as a revolutionary in Guaduas. Because she was unknown in Bogotá, she was free to move around and meet with other patriots and spies. She could also infiltrate the royalists' homes. Policarpa offered her services as a seamstress to the wives and daughters of royalists and officers, altering and mending clothing for them and their families while overhearing conversations, collecting maps and intelligence on their plans and activities, identifying who the major royalists were, and determining who was suspected of being revolutionaries.

Policarpa, with the help of her brother, secretly recruited young men for the Revolutionary cause. They worked together to increase the number of soldiers needed by the Cundinamarca insurgency.

Policarpa's operations went unnoticed until the Almeyda brothers were apprehended while transporting information back to the insurgents outside Bogotá. Their information linked La Pola directly to the Revolution. The Almeyda brothers and La Pola were involved in assisting soldiers to desert the Royal Army and join the Revolution; transporting weapons, ammunition, and supplies to the insurgents; and assisting the Almeydas in escaping from prison when they were apprehended in September of the same year and finding refuge in Machetá. They had hoped that their connection with La Pola would be useful in the event of a city revolt. The loyalists suspected her of treason, but there was insufficient evidence to charge a seamstress with espionage and treason.

The arrest of Alejo Sabaran while attempting to flee to Casanare enabled the royalists to apprehend La Pola; he was apprehended with a list of royalists and patriots provided by Policarpa.

Sergeant Iglesias, the chief Spanish officer in Bogotá, was charged with her capture and detention. Policarpa Salavarrieta and her brother Bibiano were arrested at Andrea Ricaurte y Lozano's house and taken to the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario, which had been converted into a makeshift prison.

On November 8, 1967, the Congress of the Republic of Colombia passed and President Carlos Lleras Restrepo signed Law 44, which declared November 14 to be the "Day of the Colombian Woman" in honor of the death anniversary of "our heroine, Policarpa Salavarrieta."

Policarpa Salavarrieta has appeared numerous times on Colombian currency over the years. While many idealized or mythological female figures have appeared, her portrait was the only one of an actual female historical personality ever used for a long time. Lady Liberty, Justice, an unknown Native American woman representing all indigenous peoples in Colombia, and, most recently, Mara, a fictitious character from Jorge Isaacs' novel of the same name, pictured with the author, are among the other images. The only denomination still in circulation with Policarpa Salavarrieta's image is the "Diez Mil Pesos" bill ($10,000).

elconfidencial.com

semana.com -

Gustavo Rojas Pinilla (March 12, 1900 - January 17, 1975) was a Colombian Army general, civil engineer, and dictator who served as Colombia's 19th President from June 1953 to May 1957. He is among the most important historical figures in Colombia.

During La Violencia, a period of civil strife in Colombia during the late 1940s that saw infighting between the ruling Conservatives and Liberal guerillas, Rojas Pinilla rose to prominence as a colonel and was appointed to the cabinet of Conservative President Mariano Ospina Pérez. He staged a successful coup d'état against Ospina's successor as president, Laureano Gómez Castro, in 1953, imposing martial law. He ruled the country as a military dictatorship, implementing infrastructure programs and extending female suffrage in order to reduce political violence. In 1957, he was forced to resign due to public pressure.

In 1961, Rojas Pinilla founded the National Popular Alliance (ANAPO) in opposition to the National Front, the power-sharing agreement negotiated by the Conservatives and Liberals after he was deposed. He ran for president in 1970, but was defeated by the National Front's candidate, Conservative lawyer Misael Pastrana Borrero. However, Rojas Pinilla and his supporters claimed that the election was fraudulent and illegitimate; as a result, ANAPO supporters formed the M-19 guerilla movement, which contributed to the country's insurgency unrest in the second half of the twentieth century.

radionacional.co

es.m.wikipedia.org -

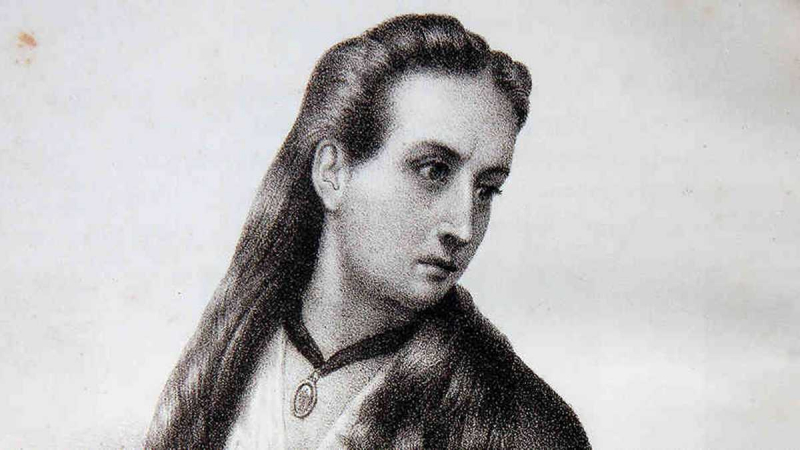

Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Ayala (23 January 1903 - 9 April 1948) was a charismatic Colombian politician from the left. He was the mayor of Bogotá from 1936 to 1937, the national Education Minister from 1940 to 1941, and the Labor Minister from 1943 to 1944. He was assassinated during his second presidential campaign in 1948, sparking the Bogotazo and the violent period of political unrest known as La Violencia in Colombian history (approx. 1948 to 1958).

Due to the chaotic public disorder, Gaitan's relatives were forced to bury him in his own house, which is now known as the Jorge Eliécer Gaitán House Museum, where his remains still rest. During the period known as La Violencia, the bipartisan violence spread to other regions.

According to an urban legend, during a debate with the Conservative candidate for president, Gaitán asked him how he made a living. "From the land," said the other candidate.

"Ah, and how did you get this land? " Gaitán inquired.

"I inherited it from my father!"

"And where did he get it from?"

"He inherited it from his father!"

The question is asked again and again until the Conservative candidate admits, "We took it from the Natives."

"Well, we want to do the opposite: we want to give the land back to the Natives," Gaitán responded.

commons.wikimedia.org

radionacional.co -

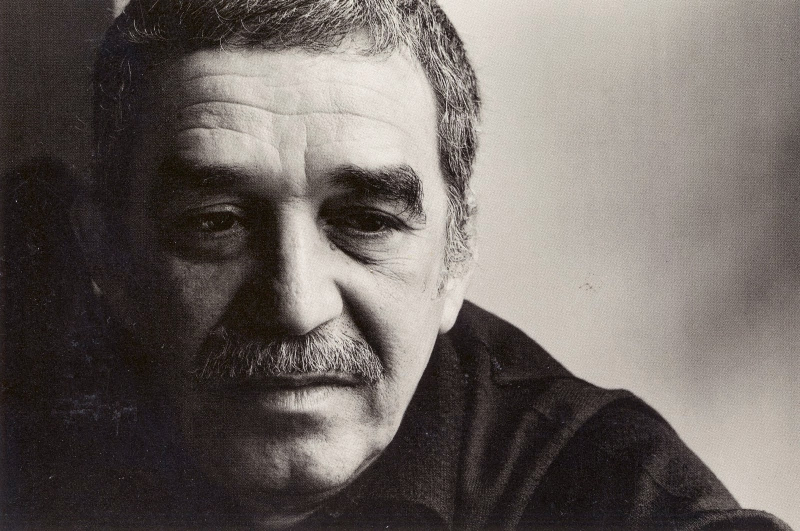

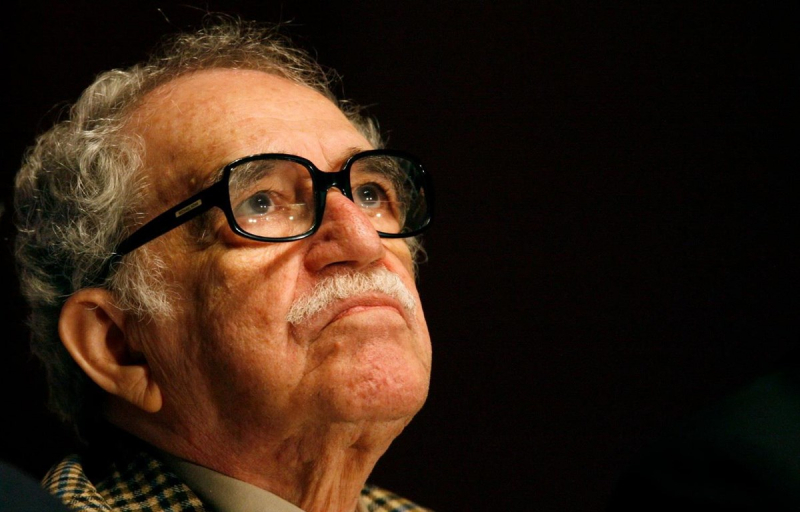

Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez (6 March 1927 - 17 April 2014) was a Colombian novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter, and journalist known affectionately throughout Latin America as Gabo or Gabito. Considered one of the twentieth century's most significant authors, particularly in the Spanish language, he received the 1972 Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature. He pursued a self-directed education that led him to leave law school for a career in journalism. He was unafraid to criticize Colombian and foreign policy from the start. He married Mercedes Barcha Pardo in 1958, and they had two sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo.

García Márquez began as a journalist and wrote numerous acclaimed non-fiction works and short stories, but he is best known for his novels, including One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981), and Love in the Time of Cholera (1985). His works have received widespread critical acclaim and commercial success, most notably for popularizing a literary style known as magical realism, which incorporates magical elements and events into otherwise ordinary and realistic situations. Some of his works are set in the fictional village of Macondo (inspired primarily by his birthplace of Aracataca), and the majority of them deal with the theme of solitude.

When García Márquez died in April 2014, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos referred to him as "the greatest Colombian who ever lived." He is remembered as one of the most important historical figures in Colombia.

holieu.org

vietnamplus.vn