Top 7 Most Important Historical Figures In Mexico

Mexico's history is full of colorful characters, from the legendary inept politician Antonio López de Santa Anna to the enormously talented but tragic artist ... read more...Frida Kahlo. Here are a few of the most important historical figures in Mexico who have left an indelible mark on the history.

-

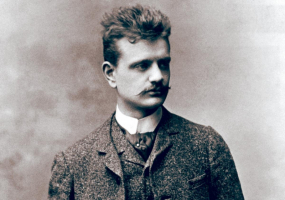

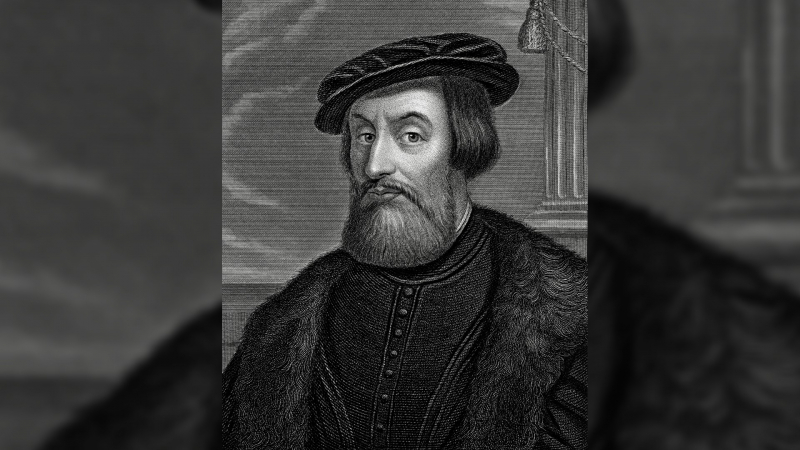

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (1485 - December 2, 1547) was a Spanish conquistador who led an expedition that brought the Aztec Empire to its knees and brought large portions of what is now mainland Mexico Cortés belonged to the generation of Spanish explorers and conquistadors who launched the first phase of Spanish colonization of the Americas.

Cortés, who was born in Medellín, Spain, to a family of lesser nobility, chose to seek adventure and riches in the New World. He traveled to Hispaniola and then to Cuba, where he was given an encomienda (the right to the labor of certain subjects). He was the alcalde (magistrate) of the second Spanish town founded on the island for a short time. In 1519, he was appointed captain of the third expedition to the mainland, which he helped to fund in part. His animosity with the Governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, resulted in the expedition being recalled at the last minute, an order that Cortés ignored.

When Cortés arrived on the continent, he used a successful strategy of allying with some indigenous people against others. He also used Doña Marina, a native woman, as an interpreter. She later gave birth to his first child. When the Governor of Cuba sent emissaries to arrest Cortés, he fought them and won, using the extra troops as reinforcements. Cortés wrote letters directly to the king, requesting recognition for his successes rather than punishment for mutiny. Cortés was given the title of Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca after overthrowing the Aztec Empire, while the more prestigious title of Viceroy was given to a high-ranking nobleman, Antonio de Mendoza. Cortés returned to Spain in 1541, where he died six years later of natural causes.

en.wikipedia.org

livescience.com -

The first bishop and archbishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga (1468-1548), was an outstanding representative of a group of 16th-century Spanish clergy in America who combined missionary zeal, a sensitive social conscience, and a love of learning. He is remembered as one of the most important historical figures in Mexico.

Juan de Zumárraga was born in the Vizcayan town of Tavira de Durango. He joined the Franciscan order as a young man and rose through its ranks to become the first bishop of Mexico in 1527. Soon after his arrival in Mexico in 1528, he clashed with the audiencia (an executive court) appointed by Charles V to govern Mexico in place of Hernán Cortés. The judges turned out to be greedy and corrupt men who only cared about enriching themselves at the expense of the Indians and the Cortés faction. Zumárraga attempted, but failed, to put an end to the audiencia's abuses of natives by combining his episcopal office with that of protector of the Indians.

Zumárraga's feud with the judges became so heated that he excommunicated the offenders and placed Mexico City under interdict. He was summoned to Spain in 1532 to justify his actions, and he did so with complete success. Meanwhile, the first audiencia had been replaced with capable and conscientious judges with whom Zumárraga had excellent relations.

Zumárraga did not oppose the encomienda despite his concern for Indian welfare (the assignment to a Spanish colonist of a group of Indians who were to serve him with tribute and labor). He believed that if properly regulated, this system could benefit both Spaniards and Indians.

Zumárraga was an inquisitor in Mexico from 1535 to 1543. He was very active in the prosecution of heresy and other violations of orthodoxy. The trial for heresy of Don Carlos, the Indian cacique of Texcoco, whom Zumárraga sentenced to death by burning, was the pinnacle of his inquisitorial career. This excessive severity earned him a reprimand from Spain and resulted in his removal from the position of inquisitor. Despite his principal biographer's earnest efforts to clear Zumárraga of the charge of destroying pre-Conquest codices, there is no doubt that he was responsible for the destruction of these and other relics of Indian history.

Zumárraga made significant contributions to Indian youth education and Mexican culture in general. In 1536, he founded the famous Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco with the assistance of Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza to train the sons of Indian chiefs. Before it began to decline in the second half of the 16th century, this school had produced a generation of Indian scholars who helped Spanish friars write important works on the history, religion, and customs of the ancient Mexicans. Zumárraga also constructed hospitals for both races, introduced the printing press to Mexico in 1539, and wrote and published books for Indian religious education.

In 1547, Zumárraga was named Mexico's first archbishop. He died in Mexico City on June 3, 1548. Zumárraga, who was heavily influenced by Erasmus' and Thomas More's Christian humanism, drew heavily on Erasmus' books for the preparation of his own writings, but only selectively, using only material that was clearly orthodox. His ideas were a synthesis of medieval and Renaissance elements, but the medieval friar in him was undeniably dominant.

prabook.com

commons.wikimedia.org -

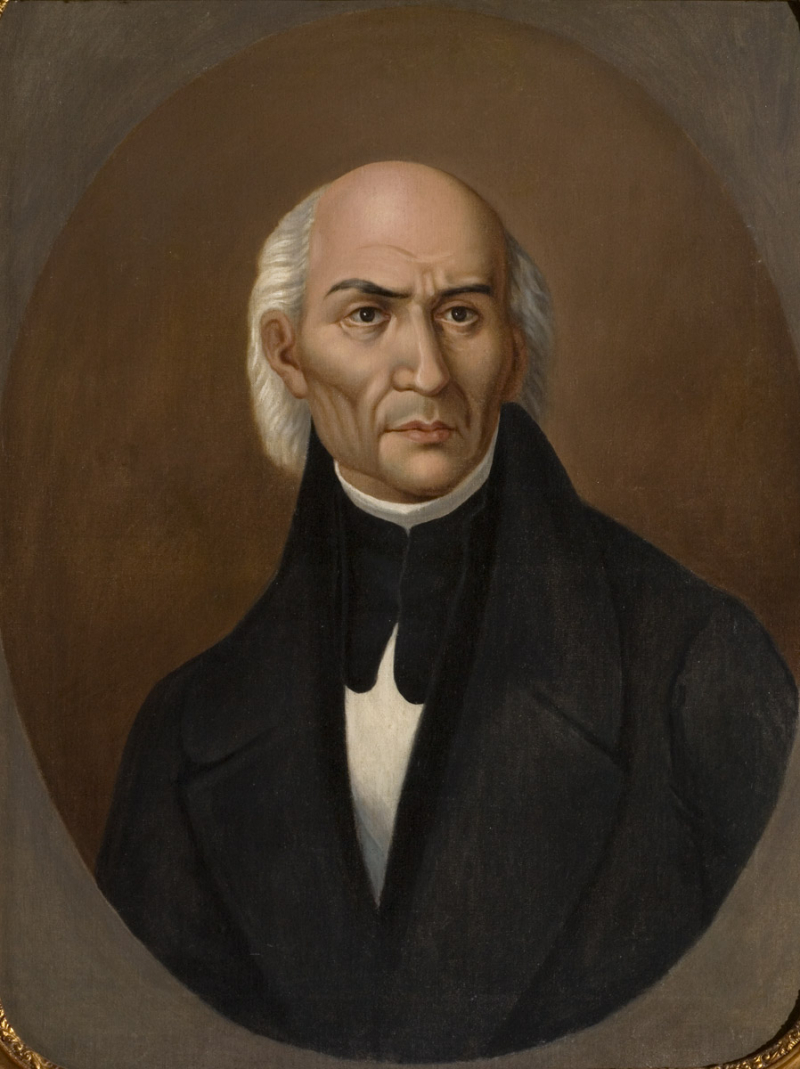

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla y Gallaga Mandarte Villaseor (8 May 1753 - 30 July 1811), also known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or Miguel Hidalgo, was a Catholic priest and leader of the Mexican War of Independence.

Hidalgo, a professor at Valladolid's Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo, was influenced by Enlightenment ideas, which contributed to his ouster in 1792. He worked in a church in Colima before moving to Dolores. He was astounded by the rich soil he discovered upon his arrival. He attempted to assist the poor by teaching them how to grow olives and grapes, but in New Spain (modern Mexico), growing these crops was discouraged or prohibited by colonial authorities in order to avoid competition with imports from Spain. On September 16, 1810, he delivered the Cry of Dolores, a speech calling on the people to protect the interests of their King Ferdinand VII, who was imprisoned during the Peninsular War, by revolting against the European-born Spaniards who.

He marched across Mexico, gathering an army of nearly 90,000 poor farmers and Mexican civilians to attack the elites of the Spanish Peninsula and the Criollo. Hidalgo's troops were poorly trained and armed. In the Battle of Calderón Bridge, these troops were defeated by an army of well-trained and armed Spanish troops. Following the battle, Hidalgo and his remaining troops fled north, but Hidalgo was betrayed, captured, and executed.

historia-biografia.com

3museos.com -

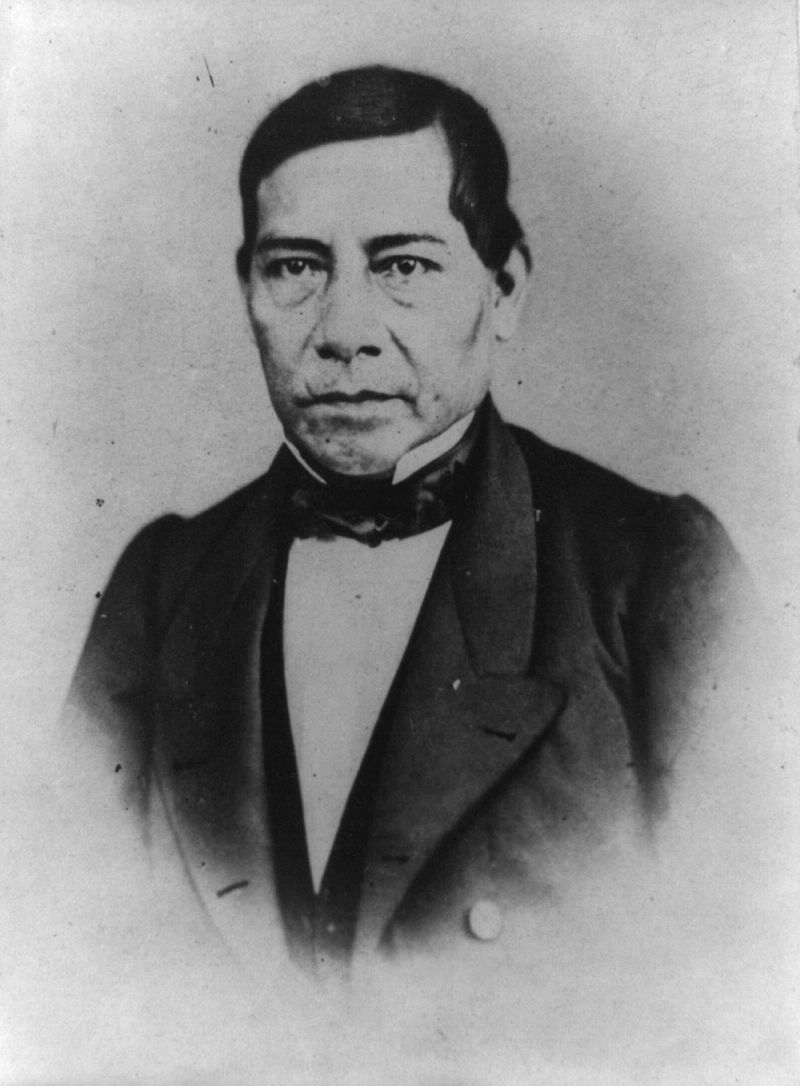

Benito Pablo Juárez Garca (21 March 1806 - 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as Mexico's 26th president from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. He was the first indigenous president of Mexico and the first indigenous head of state in the postcolonial Americas. He is among the most important historical figures in Mexico.

Juárez, who was born in Oaxaca to a poor rural family and orphaned as a child, was raised by his uncle and eventually moved to Oaxaca City at the age of 12 to work as a domestic servant. He enrolled in a seminary and studied law at the Institute of Sciences and Arts, where he became active in liberal politics with the help of a lay Franciscan. He married Margarita Maza, a woman of European ancestry from a socially distinguished family in Oaxaca City, after his appointment as a judge, and rose to national prominence after the ouster of Antonio López de Santa Anna in the Plan of Ayutla. He took part in La Reforma, a series of liberal measures implemented during the presidencies of Juan lvarez and Ignacio Comonfort that culminated in the 1857 Constitution. With Comonfort's resignation during the Reform War, Juárez assumed the constitutional presidency of Mexico as President of the Supreme Court. During the conflict, he led Mexican liberals against conservatives and defeated the Second French Intervention.

Juárez linked liberalism to Mexican nationalism and clung to power until his death in 1872. In opposition to Maximilian I, whom the French Empire installed with the support of Mexican conservatives, he asserted his leadership as the legitimate head of the Mexican state. After being elected president in 1861, he was re-elected in 1867 and 1871 to lead the Restored Republic, but with growing opposition from fellow liberals.

Juárez became known as "a preeminent symbol of Mexican nationalism and resistance to foreign intervention." He saw the United States as a model for Mexican development, in contrast to previous administrations, which had a more European-oriented political vision. His policies promoted civil liberties, equality before the law, civilian power over the Catholic Church and the military, the strengthening of the Mexican federal government, and the depersonalization of political life. Mexicans saw Juárez's tenure as a "second struggle for independence, a second defeat for the European powers, and a second reversal of the Conquest."

Following his death, the city of Oaxaca added "de Juárez" to its name in his honor, and numerous other places and institutions bear his name. He is the only person whose birthday (March 21) is observed as a national public and patriotic holiday in Mexico.

commons.wikimedia.org

commons.wikimedia.org -

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori (15 September 1830 - 2 July 1915), also known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, spanning 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 December 1876, 17 February 1877 to 1 December 1880 and from 1 December 1884 to 25 May 1911. The entire period from 1876 to 1911, which has been described as a de facto dictatorship. He is among the most important historical figures in Mexico.

Veteran of the Reform War (1858-1860) and the French intervention in Mexico (1862-1867), Díaz rose to the rank of general, leading republican troops against Maximilian I's French-imposed rule. He later revolted against presidents Benito Juárez and Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada on the principle of no re-election. Díaz was successful in seizing power, deposing Lerdo in a coup in 1876 with the assistance of his political supporters, and was elected in 1877. He stepped down in 1880, and his political ally Manuel González was elected president and served from 1880 to 1884. Díaz abandoned the idea of not running for re-election in 1884 and remained in office until 1911.

Díaz's regime, a controversial figure in Mexican history, ended political instability and achieved economic growth after decades of stagnation. He and his allies were members of a group of technocrats known as científicos ("scientists"), whose economic policies benefited a circle of allies and foreign investors, assisting hacendados in consolidating large estates, often through violent means and legal abuse. These policies became increasingly unpopular, resulting in civil repression and regional conflicts, as well as strikes and uprisings from labor and the peasantry, groups that did

Despite making public statements in 1908 favoring a return to democracy and declining to run for office again, Díaz reversed his position and ran in the 1910 election. After Díaz declared himself the winner for an eighth term, his electoral opponent, wealthy estate owner Francisco I. Madero, issued the Plan of San Luis Potos calling for armed rebellion against Díaz, sparking a political crisis between the cientificos and the followers of General Bernardo Reyes, allied with the military and peripheral regions of Mexico. After the Federal Army suffered several defeats against Madero's forces in May 1911, Díaz resigned in the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez and went into exile in Paris, where he died four years later.

vi.wikipedia.org

infobae.com -

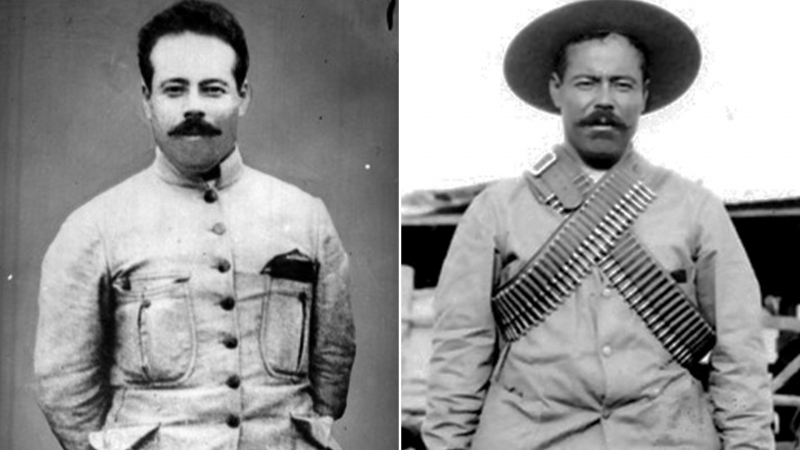

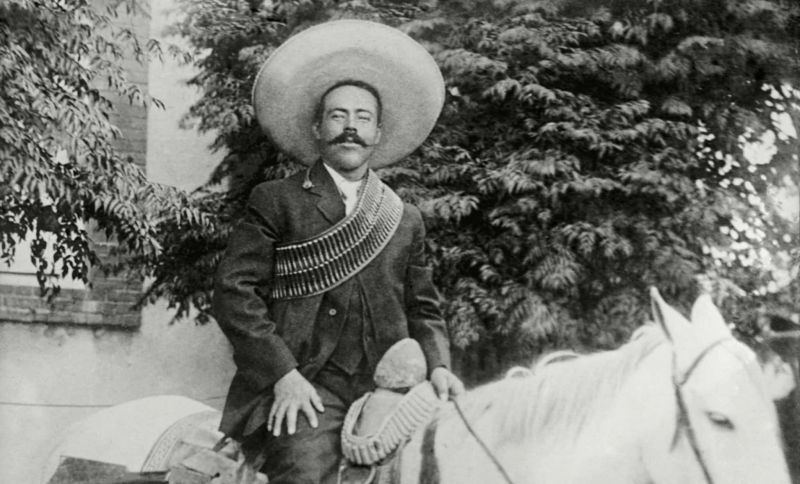

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, 5 June 1878 - 20 July 1923) was a Mexican Revolutionary War general. He was a pivotal figure in the revolutionary movement that deposed President Porfirio Díaz and installed Francisco I. Madero as President in 1911. When Madero was deposed in February 1913 by a coup led by General Victoriano Huerta, he led anti-Huerta forces in the Constitutionalist Army 1913-1914. Venustiano Carranza, the civilian governor of Coahuila, led the coalition. Villa broke with Carranza after Huerta's defeat and exile in July 1914. Villa presided over a meeting of revolutionary generals that excluded Carranza and aided in the formation of a coalition government. During this time, Emiliano Zapata and Manuel Villa became formal allies, but only in theory. Villa, like Zapata, was a strong supporter of land reform, but his plans were not carried out while he was in power.

At the height of his power and popularity in late 1914 and early 1915, the United States considered recognizing him as Mexico's legitimate authority. Villa was decisively defeated by Constitutionalist General lvaro Obregón in the summer of 1915, and the United States aided Carranza directly against Villa in the Second Battle of Álvaro Obregón in November 1915. Villa, enraged by the United States' assistance to Carranza, conducted a raid on the border town of Columbus, New Mexico in 1916-17 to provoke the United States to invade Mexico. Despite a large contingent of soldiers and cutting-edge military technology, the United States was unable to capture Villa. When President Carranza was deposed in 1920, Villa negotiated an amnesty with interim President Adolfo de la Huerta and was given a landed estate in exchange for his political retirement. In 1923, he was assassinated. Despite the fact that his faction did not win the Revolution, he is one of its most charismatic and prominent figures.

During his life, Villa helped shape his own image as an internationally known revolutionary hero, starring as himself in Hollywood films and giving interviews to foreign journalists, most notably John Reed. After his death, he was excluded from the pantheon of revolutionary heroes until the Sonoran generals Obregón and Calles, whom he fought against during the Revolution, had passed away. Villa's exclusion from the official Revolutionary War narrative may have contributed to his posthumous popular acclaim. Corridos, films about his life, and novels by prominent writers all paid tribute to him during the Revolution and long after. In 1976, his ashes were reburied in Mexico City's Monument to the Revolution in a massive public ceremony.

infobae.com

alma-de-chiapas.com -

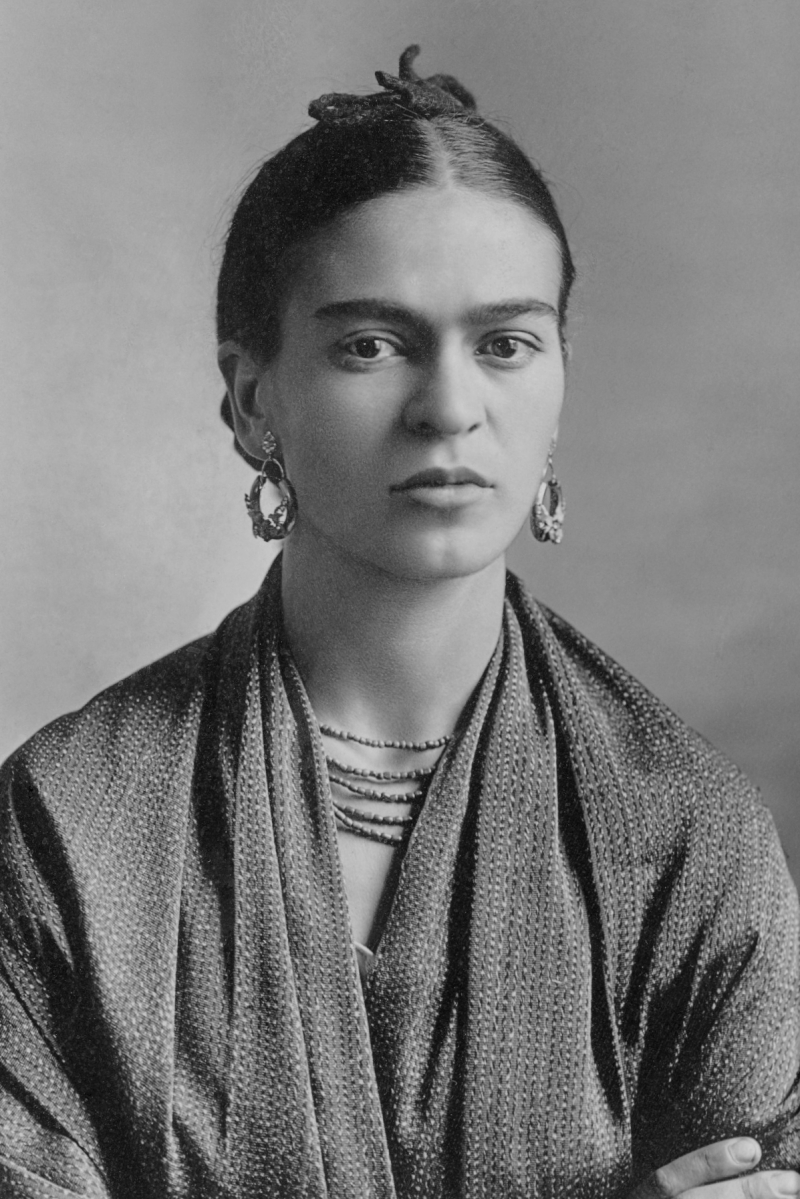

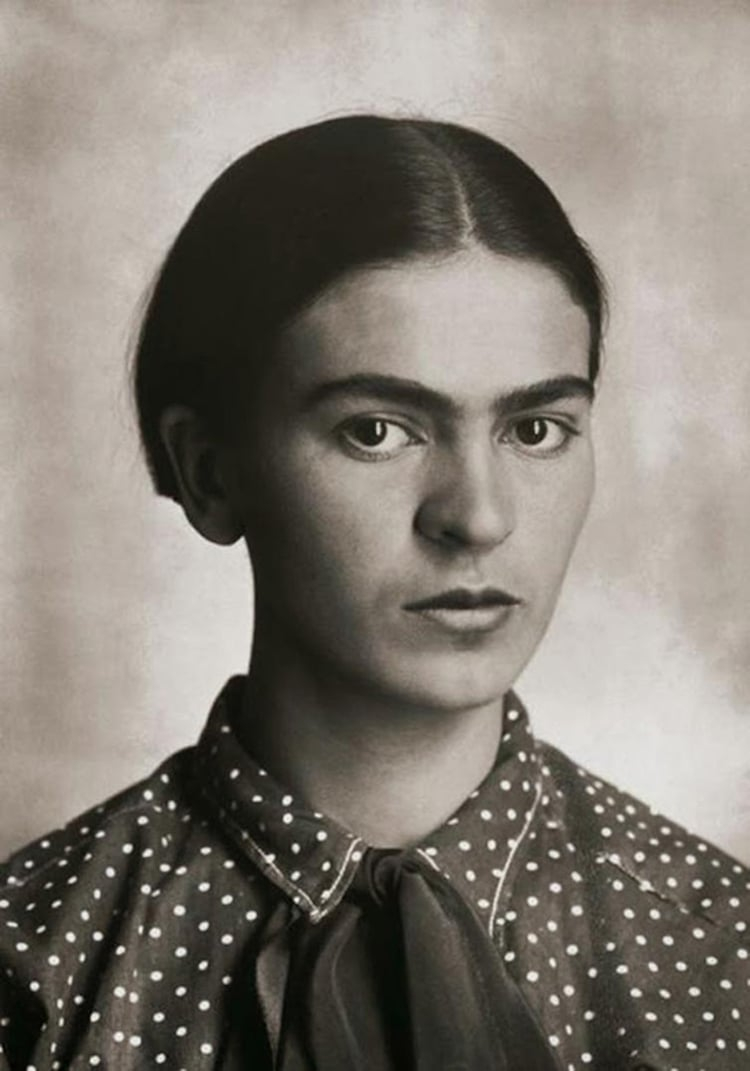

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (July 6, 1907 - July 13, 1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by Mexican nature and artifacts. She used a naive folk art style inspired by Mexican popular culture to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society. Her paintings frequently had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to being a member of the post-revolutionary Mexicayotl movement, which sought to define Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a surrealist or magical realist. She is well-known for painting about her chronic pain experience. Now she is regarded as one of the most important historical figures in Mexico.

Kahlo spent the majority of her childhood and adult life at La Casa Azul, her family home in Coyoacán, which is now open to the public as the Frida Kahlo Museum. Despite having polio as a child, Kahlo was a promising student on her way to medical school until she was injured in a bus accident at the age of 18, which caused her lifelong pain and medical problems. During her rehabilitation, she revisited her childhood interest in art, with the goal of becoming an artist.

Kahlo's political and artistic interests led her to join the Mexican Communist Party in 1927, where she met fellow Mexican artist Diego Rivera. The couple married in 1929 and traveled together in Mexico and the United States during the late 1920s and early 1930s. During this time, she developed her artistic style, drawing inspiration primarily from Mexican folk culture, and painted mostly small self-portraits that incorporated elements from pre-Columbian and Catholic beliefs. Her paintings piqued the interest of Surrealist artist André Breton, who arranged for Kahlo's first solo exhibition in New York at the Julien Levy Gallery in 1938; the exhibition was a success, and it was followed by another in Paris in 1939. While the French exhibition was less successful, the Louvre purchased a painting by Kahlo, The Frame, making her the first Mexican artist to be included in their collection. She was a founding member of the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana and taught at the Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado ("La Esmeralda"). In the same decade, Kahlo's always-fragile health began to deteriorate. She had her first solo exhibition in Mexico in 1953, just before her death at the age of 47 in 1954.

Kahlo's work as an artist was relatively unknown until the late 1970s, when art historians and political activists rediscovered it. Not only had she become a recognized figure in art history by the early 1990s, but she was also regarded as an icon for Chicanos, the feminism movement, and the LGBTQ+ movement. Kahlo's work has been praised internationally as a symbol of Mexican national and indigenous traditions, as well as by feminists for its uncompromising depiction of female experience and form.

en.wikipedia.org

nld.com.vn