Top 8 Outstanding Examples of Mesopotamian Art

Each of these civilizations left behind stunning specimens of their art throughout history. The pyramids and other magnificent monuments to their dead were ... read more...left by the Egyptians. In the Mediterranean region, the Greeks and Romans left innumerable temples and monuments. The Chinese left behind many things, including books and terracotta figures and Mesopotamian is not the exception. Here are the most outstanding examples of Mesopotamian art.

-

The Ishtar Gate was Babylon's eighth inner-city gate (in the area of present-day Hillah, Babil Governorate, Iraq). On the north side of the city, it was built around 575 BCE at the king's command. It was a section of the city's grand processional road, which was enclosed by a wall. The walls were finished in primarily blue glazed bricks with low reliefs of animals and gods that were also constructed of bricks that have been shaped and colored differently. Many people today believe that the Ishtar Gate is the most outstanding example of Mesopotamian art.

Large in size, the gate is 100 feet wide and 14 feet high. Its golden and yellow mosaics gave away the fact that one was entering a wealthy and strong city, and its crenelated towers demonstrate architectural ability. Restorers surmise that lapis lazuli was used to tint or cover the Ishtar Gate based on dye and paint residue. The pricey lapis paint highlights the significance of the building. Two of the main gods of the Babylonian pantheon are depicted repeatedly in a low relief artwork on the front of the gate. The national deity and chief god Marduk is shown as a dragon with a snake-like head and tail, a lion's scaled torso, and strong talons for back feet. The Ishtar gate's bricks were constructed from finely textured clay that was pressed into wooden molds. Additionally, the bricks used to build each of the animal reliefs were created by squeezing clay into reusable molds. The brilliant blue background glazes, which mimic the hue of the highly valuable lapis lazuli, predominate. The glazes utilized for animal images are gold and brown. Black, white, and gold glaze is used for the rosettes and borders.

The Ishtar Gate was supposedly just the last building on a long route heading into the city's north side. The road leading to the gate is thought to have been lined with small castle towers, all of which were crenelated like the top of the Ishtar Gate. It is unclear if this was done merely for aesthetic purposes, to defend archers, or both.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: World History Encyclopedia -

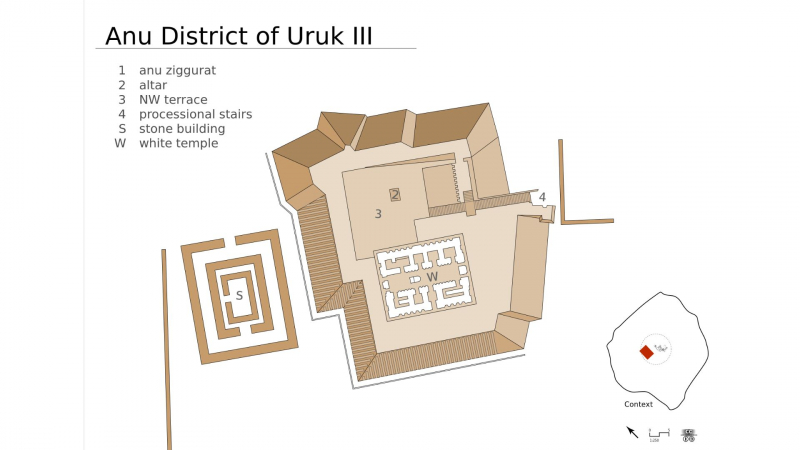

The White Temple and Great Ziggurat, the most significant temple to the gods for the Sumerians, are found in Uruk, which is situated on the Euphrates in what is currently southeast Iraq. The legendary Sumerian hero Gilgamesh, who is depicted in the renowned epic poem of the same name, lived in Uruk, a significant city in early Sumerian culture and one of the first examples of narrative that has survived to the present day. Today, the ruins of one of ancient Sumer's most significant temples broil in the Iraqi sun. It takes a lot of imagination for tourists, historians, and archaeologists to imagine the ziggurat as it actually was 5,000 years ago. Despite the damage caused by time, the sun, the wind, and erosion, we can extrapolate from archeological data and literature to create a picture of the structure's appearance during the height of Sumer's supremacy.

The Sumerians built many of their temples on the highest points and as tall as the available building technology allowed because, like many other cultures, they believed the gods resided in the sky. A ziggurat is a pyramid with steps. It is a broad one in this instance, with a sizable flat region at the top where a huge temple was built. Here, priests would pray to the gods, make sacrifices, and listen for messages from the gods. The White Temple had a surface area of 56 x 72 square feet and was 40 feet (12 meters) high. It was made of brick because usable stone was scarce in the area (17 x 22 square meters). According to historians, the temple was built over the course of five years by 1,500 workers. Archaeologists have discovered the burned skeletons of a leopard and a lion within the temple, as well as a number of stone tablets that record the temple's financial transactions and a burn pit where it is thought that burnt sacrifices were offered to the gods.

Photo: Smarthistory

Photo: Wikipedia -

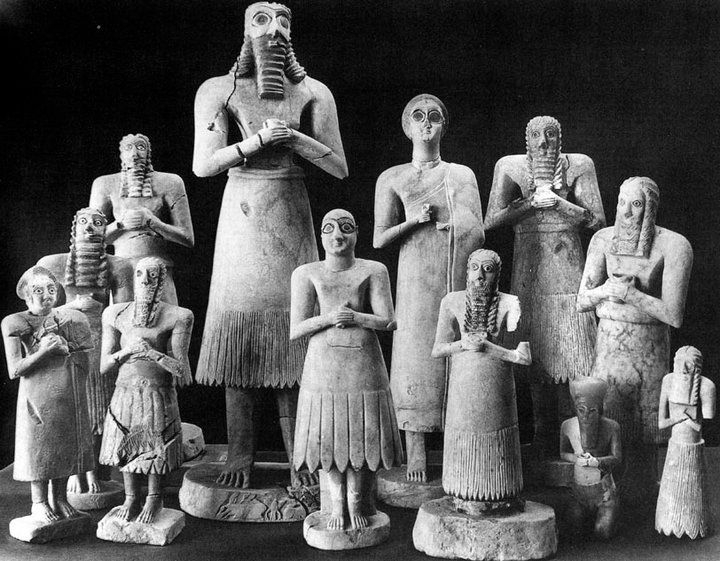

Statues of Tell Asmar is the next outstanding example of Mesopotamian art. Twelve sculptures known as the Tell Asmar Hoard (Early Dynastic I-II, approx. 2900-2550 BC) were discovered in 1933 in Eshnunna (current-day Tell Asmar), in the Diyala Governorate of Iraq. They continue to be the only examples of the abstract style of Early Dynastic temple sculpture, despite subsequent discoveries at this site and elsewhere in the larger Mesopotamian region (2900 BC–2350 BC). The desert east of the Diyala River, just north of its confluence with the Tigris, was a major source of unique, high-quality antiquities for Baghdad's antique dealers in the late 1920s. The twelve statues together referred to as the Tell Asmar Hoard are among the most well-known and well-preserved artifacts. The trove was discovered at Tell Asmar during the 1933–1934 excavation season beneath the floor of a temple honoring the god Abu. In the sanctuary, the sculptures were arranged neatly in an oblong chamber next to an altar. The exact positioning shows that they were buried on purpose. However, it is still unknown why the body was buried and who, if anyone, was behind it.

The Tell Asmar Hoard's statues are between 8.2 inches and 72 centimeters tall (28.3 in.). Ten of the discovered statues are male and two are female. Two of the figurines are made of limestone, one (the smallest) of alabaster, and eight of the figures are made of gypsum. [4]: 57–59 All of the figures are depicted in a standing stance, with the exception of one that is kneeling. Large wedge-shaped feet gave the larger statues extra resilience, while thin circular bases were employed as supports. The males dress in patterned kilts that cover their thighs and midsection. The bare chest, which is partially framed by a black, styled beard, is framed by their large shoulders and thick, circular arms. The statues' huge eyes, which are unquestionably the most prominent artistic element in common, are crafted from inlays of white shell and black limestone; one of the figures has lapis lazuli pupils.

Photo: Reddit

Photo: Pinterest -

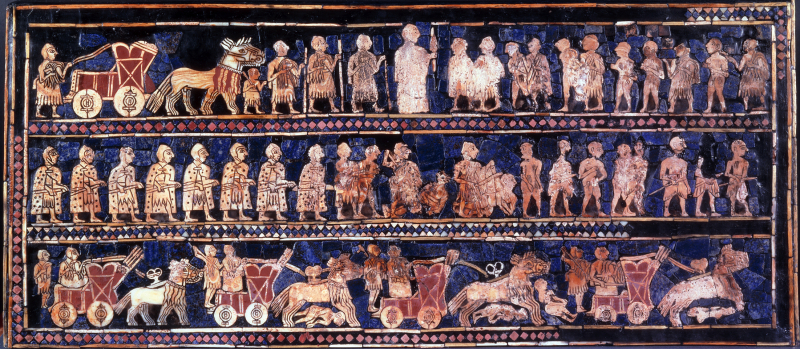

The British Museum currently has The Standard of Ur, a Sumerian artifact from the third millennium BC. It is made out of a hollow wooden box that is 49.53 centimeters (19.50 in) long and 21.59 centimeters (8.50 in) wide, and it is inlaid with a mosaic of lapis lazuli, red limestone, and shell. It is from the historic city of Ur (located in modern-day Iraq west of Nasiriyah). It is approximately 4,600 years old and dated to the First Dynasty of Ur during the Early Dynastic era. The standard was most likely built in the shape of a hollow wooden box with scenes of conflict and peace depicted on each side by intricately inlaid mosaics. Although its discoverer saw it as a standard, its original intent is still unclear. It was discovered in a royal tomb in Ur in the 1920s adjacent to the skeleton of a man who may have been its bearer and who had been ritually sacrificed.

The mosaic, which was first thought to be covering a hollow, four-sided box, is actually fairly modest, yet it contains a wealth of information about various facets of ancient Mesopotamian society. The two pieces that have survived have been given the names "War" and "Peace." The first depicts the king as a two-dimensional, enormous person watching a column of nude, often wounded, prisoners being dragged past his chariot. In their helmets and with their weapons ready, Mesopotamian troops are depicted.

It is unclear with certainty what the Standard of Ur's original purpose was. It is now seen as improbable that Woolley's claim that it represented a standard was true. It has also been conjectured that it was a musical instrument's soundbox. Paola Villani hypothesizes that it was used as a chest to hold resources for war or charitable endeavors. As there is no inscription on the artifact to provide any background information, it is hard to know for sure.

Photo: Wikipedia

Photo: World History Encyclopedia -

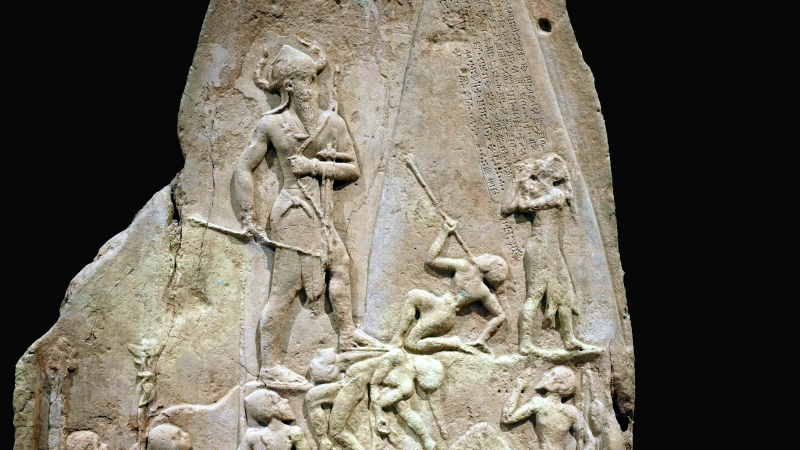

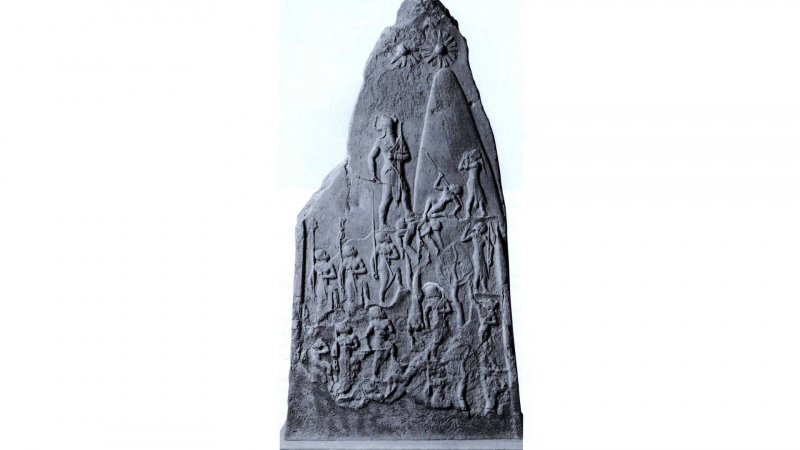

Located at the Louvre in Paris, the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin is a stele that dates to roughly 2254–2218 BC, during the Akkadian Empire. The 200cm (6' 7") tall relief was carved from pink limestone and has writings in Akkadian and Elamite. It shows the Lullubi, a mountain people from the Zagros Mountains, being defeated by the Akkadian army under the command of King Naram-Sin of Akkad.

The stele depicts a story in which the monarch scales the treacherous mountains into enemy territory. On the left, the orderly imperial armies march over the disorganized defenders who are lying broken and vanquished. The most significant character is clearly Naram-Sin, who towers over his adversaries and army and is the focus of all attention. The disorganized and feeble opposing forces are depicted being flung off the mountainside, pierced by spears, running away, pleading with Naram-Sin for mercy, and being crushed under Naram-feet. Sin's. This is meant to suggest that they are uncivilized and primitive, which justifies the conquering. Estimates of its initial height range up to three meters, despite the fact that it is currently just about two meters tall.

The stele is distinctive in two ways. Most representations of conquests are horizontal, with the king positioned top-center. The king is still at the top-center of this steele's diagonal representation of the victory, but he is now in a position where everyone else can look up to him. The depiction of Naram-Sin as having bull horns on his helmet or appearing as a lion's visage is the piece's second distinctive feature. At the time this stele was ordered, only the Gods wore helmets of this kind. This stele is essentially telling the observer that Naram-divine Sin's status makes him a successful conqueror. That's all about the fifth outstanding example of Mesopotamian art we want to mention.

Photo: Smarthistory

Photo: American Historical Association -

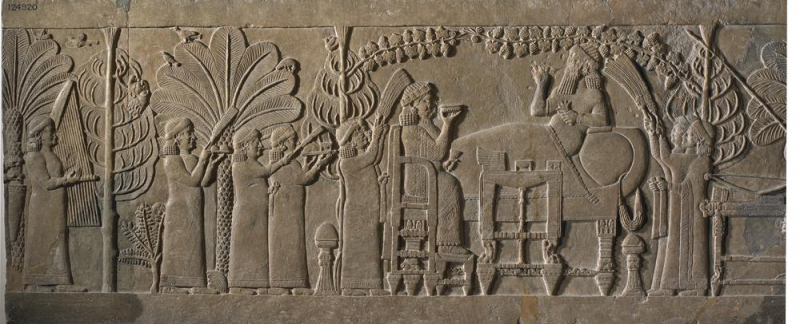

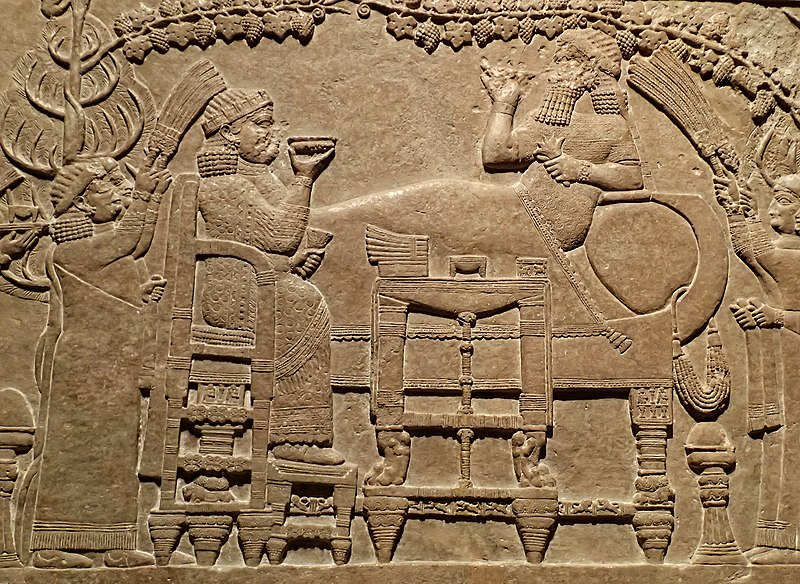

Ashurbanipal was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is often regarded as the final great Assyrian king. Ashurbanipal had one of the longest reigns of any Assyrian kings, ruling for 38 years after being chosen as his father Esarhaddon's preferred heir. Assyrian artwork from the Ancient Near East includes Assurbanipal and His Queen in the Garden. This panel shows a large crowd joyfully assisting and encircling what appears to be a wealthy couple in a garden. Assurbanipal and His Queen in the Garden gives the appearance of a regal, unhurried hero. This clearly demonstrates the sway that era's citizens held over their king.

This low-saturation light brown alabaster panel has serene low relief carvings that don't draw undue attention from the viewer. The panel's block-like characters focus the viewer's attention on the two figures on the right side of the picture and their imposing presence. The lines of the vines that appear to encircle the king and queen draw attention to them. The arrangement of the people themselves does not fill the full panel; rather, it leaves room for the viewer to see the garden in the distance, lending the carved panel a feeling of peace, rest, and relaxation. This artwork exudes relaxation throughout. While the other servants deliver food and drink to the regal couple, a figure in the far left side is playing a harp. The two prominent people appear to be being fanned by at least four of the attendants as they eat and drink. With one foot in front of the other, the servants appear to be moving in the direction of the royal couple. The garden exudes serenity. The palms are lined up as the trees extend out in a beautiful pattern.

Photo: British Museum

Photo: Wikipedia -

One of the earliest stringed instruments ever found is the Bull Headed Lyre. It is considered as one of the most outstanding examples of Mesopotamian art. The lyre was discovered during the 1926–1927 season of an archaeological dig conducted jointly by the University of Pennsylvania and the British Museum in what is now Iraq in the Royal Cemetery of Ur. The excavations were headed by Leonard Woolley. The lyre was discovered next to more than sixty soldiers' and attendants' corpses in "The King's Grave." It is one of several lyres and harps from the Early Dynastic III Period discovered at the cemetery (2550–2450 BCE). The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (the Penn Museum) received the lyre as part of the initial shipment of items in 1929. The object is made up of a quadripartite panel, a sound box, and a sculptured bull's head. It has undergone substantial conservation and repair work throughout the years.

The character most commonly mentioned in some ancient inscriptions as having a lapis lazuli beard is the Mesopotamian sun god Utu/Shamash. He was frequently believed to take the shape of a bull, especially in his duty at daybreak. For these reasons, the Penn Museum claims that Utu/Shamash is represented by the bull head on the lyre. The head was constructed of a single piece of gold plating over a wooden core that has since crumbled, and the ears and horns were fastened to the skull with tiny pegs. Carved lapis lazuli tesserae on a silver backing are used to create the beard.

A front panel of the lyre features four scenes related to Early Mesopotamian burial rites. Shell inlay is used to create the designs on the bitumen. In the first panel, two bulls with human heads are being wrestled by a guy. The second depicts a lion carrying a jar and a hyena carrying meat. The third depicts an animal holding a rattle and playing a bull-shaped lyre while being supported by a bear. In the lowest register, a man is greeted by a scorpion guarding the underworld. Utu / Shamash served as the judge of the dead in addition to being the sun deity. He appears to be overseeing the events depicted in the panel attached below his head in the lyre.

Photo: World History Encyclopedia

Photo: Penn Museum -

The lamassu were guardian deities in Mesopotamian mythology who had human heads, lion or bull bodies, and bird wings. The lamassu guarded temples and palaces in much the same way that Chinese guardian lions, lion dogs, and dragons did in order to safeguard the safety of the king and priests and the protection of prayers. Most people relate the visage of the lamassu to the features of Mesopotamian kings or priests. They have a long, square-ended beard that is curled and is worn with a tall hat with a flat top, resembling a miter. People frequently connect the face of the lamassu with the kings of Mesopotamia, much like we think of King Tut or the Sphinx as representative of ancient Egypt.

As the protectors of the temples and the entrances to the gods, the majority of the lamassu figures that have survived are huge and formidable. At Sargon II's temple in Khorsabad, northern Iraq, the most famous pair of lamassu stands significantly higher and wider than the people. The fact that these bull- or lion-bodied guardians frequently have five legs is another intriguing aspect about them. These human-animal hybrids, like the Lamassu, often appeared in pairs and served as guardians against supernatural forces from without. Its five legs can be seen from either the front, where it is shown standing firm with two legs planted against a threat, or from the side, where it is shown advancing against evil with four long, powerful legs.

Photo: Ancient Origins

Photo: Khan Academy