Top 8 Things to Know about Halloween

Halloween is a holiday that is observed every October 31; in 2022, it will fall on a Monday. The custom has its roots in the ancient Celtic holiday of Samhain ... read more...when people would dress up and light bonfires to fend off ghosts. Pope Gregory III established November 1 as a day to celebrate all saints in the eighth century. Soon, some of Samhain's customs were incorporated into All Saints Day. Before Halloween, the previous evening was referred to as All Hallows Eve. Halloween has changed over the years to become a day filled with festivities like trick-or-treating, carving jack-o-lanterns, festive get-togethers, dressing up, and enjoying sweets. Read our article about things to know about Halloween to gain a deeper understanding of this holiday.

-

Halloween's roots can be found in the historic Samhain festival of the Celts (pronounced sow-in). On November 1, the Celts, who lived 2,000 years ago in a region that is now primarily Ireland, the United Kingdom, and northern France, celebrated the beginning of their new year. This day marked the end of summer and harvest and the start of the dark, cold winter, a time of year that was often associated with human death. The night before the new year, according to the Celts, the line separating the living from the dead grew hazy. On the evening of October 31, they observed Samhain, a time when it was thought that the spirits of the dead made a comeback to the planet.

In addition to causing havoc and destroying crops, Celts believed that the presence of otherworldly spirits made it easier for Druids, or Celtic priests, to predict the future. These prophecies were an important source of comfort during the long, dark winter for people who were completely dependent on the volatile natural world. Druids built massive sacred bonfires to commemorate the event, where people gathered to burn crops and animals as sacrifices to the Celtic deities. During the celebration, the Celts dressed up in animal heads and skins and attempted to tell each other's fortunes. They re-lit their hearth fires, which they had put out earlier that evening, from the sacred bonfire after the celebration was over in order to help protect them during the upcoming winter.

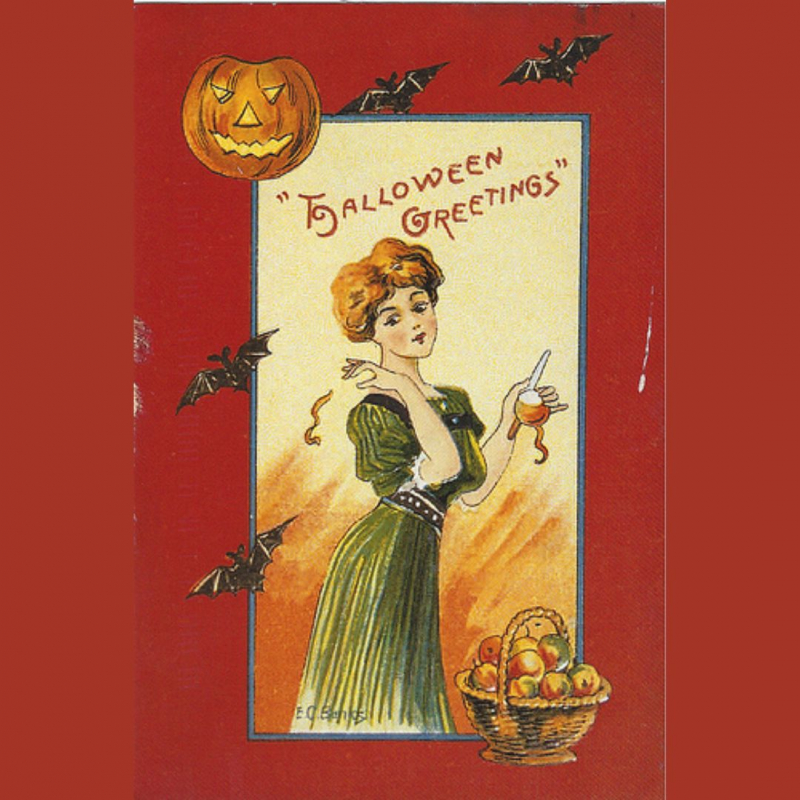

The majority of Celtic lands had been conquered by the Roman Empire by the year 43. Over the course of their 400-year reign over the Celtic lands, two Roman-inspired holidays were merged with the customary holiday of Samhain. The first was Feralia, a Roman tradition that takes place in late October to remember the deceased. Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and trees, was celebrated on the second day. The apple is Pomona's emblem, so the fact that this celebration was incorporated into Samhain probably explains why we still bop for apples on Halloween today.

Museum of Arts & Science

Ligonier Valley Historical Society -

The origin of the modern English name Halloween can be found in medieval Christianity. The Middle and Old English words for holy are where the word hallow comes from. It also has the noun meaning of saint. The day before All Hallows' Eve, when an evening mass was held, was All Hallows' Eve, and it was the Christian holiday we now know as All Saints' Day. Eventually, that three-word name was abbreviated to Halloween.

Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon in Rome to all Christian martyrs on May 13, A.D. 609, and the Catholic feast of All Martyrs Day was established in the Western church. Later, Pope Gregory III expanded the festival to include all saints and martyrs and moved the celebration from May 13 to November 1.

By the 9th century, Christianity's influence had spread into Celtic lands, gradually blending with and supplanting older Celtic rites. The church declared November 2 All Souls' Day, a day to honor the dead, in A.D. 1000. Today, it is widely assumed that the church attempted to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related, church-sanctioned holiday.Similar to Samhain, All Souls Day was observed with large bonfires, parades, and dressing as saints, angels, and demons. The holiday known as All Saints' Day is also known as All-Hallows or All-Hallowmas (from the Middle English word all-holowmesse, which means All Saints' Day), and the night before it, known as Samhain in the Celtic religion, started to be called All-Hallows Eve and then, eventually, Halloween.

Catholic News Agency

Franciscan Media -

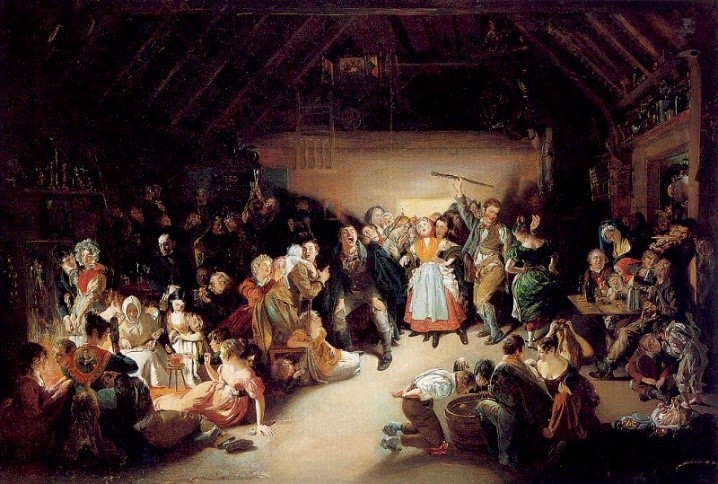

Borrowing from European traditions, Americans began dressing up in costumes and going door to door asking for food or money, a practice that evolved into today's "trick-or-treat" tradition. Young women believed that by performing tricks with yarn, apple parings, or mirrors on Halloween, they could divine the name or appearance of their future husband.

In the late 1800s, there was a movement in America to make Halloween a holiday about community and neighborly gatherings rather than ghosts, pranks, and witchcraft. Halloween parties for both children and adults became the most popular way to celebrate the holiday around the turn of the century. Parties centered on games, seasonal foods, and festive costumes.

Newspapers and local authorities urged parents to remove anything "scary" or "grotesque" from Halloween celebrations. By the start of the twentieth century, Halloween had largely lost its superstitious and religious connotations as a result of these efforts.

www.history.com

families, LoveToKnow -

Colonial New England's strict Protestant religious beliefs severely restricted the Halloween festivities. In Maryland and the southern colonies, Halloween was much more common.

A uniquely American interpretation of Halloween started to take shape as the beliefs and traditions of various European ethnic groups and American Indians converged. The first harvest celebrations included "play parties," which were open-air gatherings. Neighbors would sing and dance while exchanging ghost stories and fortunes.

Colonial Halloween celebrations also included the telling of ghost stories and various forms of mischief. Annual autumn festivities were common by the middle of the nineteenth century, but Halloween was not yet celebrated throughout the country.

America was flooded with new immigrants in the second half of the nineteenth century. These newcomers, particularly the millions of Irish fleeing the Irish Potato Famine, helped to popularize Halloween across the country.

www.history.com

Piccola New Yorker Special Trips -

By the 1920s and 1930s, Halloween had evolved into a secular but neighborhood-focused celebration, with parades and Halloween parties serving as the main attractions. Vandalism started to affect some celebrations in many communities during this time, despite the best efforts of many schools and communities.

By the 1950s, town officials had successfully reduced vandalism, and Halloween had changed into a celebration primarily for kids. The baby boom of the 1950s produced a large number of young children, so celebrations moved from town civic centers to classrooms and homes where they could be accommodated more easily.

The centuries-old practice of trick-or-treating was also revived between 1920 and 1950. Trick-or-treating was a low-cost way for an entire community to participate in the Halloween celebration. In theory, families could also prevent tricks from being played on them by providing small treats to the neighborhood children.

As a result, a new American tradition was born, and it has since grown. Halloween now accounts for an estimated $6 billion in annual spending in the United States, making it the country's second-largest commercial holiday after Christmas.

Let's Roam

VnExpress -

Trick-or-treating on Halloween in America likely originated with early All Souls' Day parades in England. Poor people would beg for food during the festivities, and in exchange for their promise to pray for the family's deceased relatives, families would give them treats called "soul cakes."

The church promoted the distribution of soul cakes as a replacement for the traditional custom of leaving food and wine out for wandering spirits. Children eventually adopted the custom of "going a-souling," where they would visit the homes in their neighborhood and receive ale, food, and money.

The Halloween costume tradition has both European and Celtic origins. Winter was an uncertain and frightening time hundreds of years ago. Food supplies frequently ran low, and the short days of winter were fraught with anxiety for many people who were afraid of the dark.

People expected to encounter ghosts if they left their homes on Halloween when it was believed that ghosts returned to the earthly world. People would wear masks when leaving their homes after dark to avoid being recognized by these ghosts, hoping that the ghosts would mistake them for fellow spirits.In order to deter ghosts from trying to enter homes on Halloween, people used to leave bowls of food outside. This would appease the ghosts and keep them away.

The Inn at the Crossroads Tasting History with Max Miller's Channel -

Halloween has always been a mystery, magic, and superstition-filled holiday. It began as a Celtic end-of-summer festival when people felt particularly close to deceased relatives and friends. They set places at the dinner table, left treats on doorsteps and along the side of the road, and lit candles to assist loved ones in finding their way back to the spirit world.

Today's Halloween ghosts are frequently depicted as more fearsome and malevolent, as are our customs and superstitions. We avoid black cats because we are afraid they will bring us bad luck. This belief dates back to the Middle Ages when many people believed that witches avoided detection by transforming into black cats.

We make an effort to avoid using ladders as footholds. It's possible that this superstition originated with the ancient Egyptians, who thought triangles were sacred (it also may have something to do with the fact that walking under a leaning ladder tends to be fairly unsafe). And especially around Halloween, we make an effort to avoid damaging mirrors, stepping on potholes, and spilling salt.

www.history.com

WallpaperBetter -

Many Halloween traditions and beliefs centered on the future rather than the past, and on the living rather than the dead.

Many had to do with assisting young women in identifying potential husbands and assuring them that they would be married someday, hopefully by next Halloween. On Halloween night in 18th-century Ireland, a matchmaking cook might bury a ring in her mashed potatoes, hoping that the diner who found it would find true love.

In Scotland, matchmakers advised young women to name a hazelnut for each potential suitor before throwing the nuts into the fireplace. According to the legend, the nut that burned to ashes instead of popping or exploding represented the girl's future husband. In other versions of this myth, the opposite was true: the burning nut represented a fleeting love.

Another legend claimed that a young woman would dream about her future husband if she consumed a sugary mixture made of walnuts, hazelnuts, and nutmeg before going to bed on Halloween night.Young women tossed apple peels over their shoulders, hoping for the peels to fall on the floor in the shape of their future husbands' initials; peered at egg yolks floating in a bowl of water to learn about their futures; and stood in front of mirrors in darkened rooms, holding candles and looking over their shoulders for their husbands' faces.

Other rituals were more competitive in nature. The first guest to find a burr on a chestnut hunt at some Halloween parties would be the first to marry. Others believe that the first successful apple bobber will be the first down the aisle.Of course, each of these Halloween superstitions depends on the goodwill of the very same "spirits" whose presence the early Celts felt so keenly, whether people are seeking love advice or hoping to ward off seven years of bad luck.

messynessychic.com

messynessychic.com