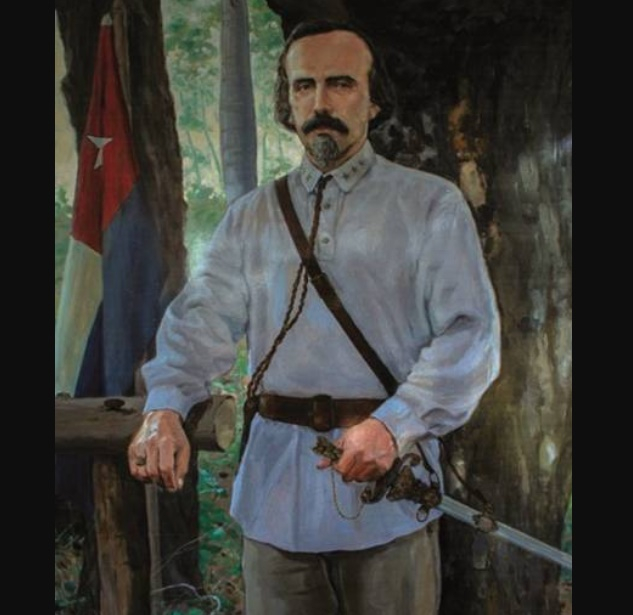

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes del Castillo

One of the most important historical figures in Cuba is Carlos Manuel de Céspedes del Castillo. He (18 April 1819, Bayamo, Spanish Cuba – 27 February 1874, San Lorenzo, Spanish Cuba) was a Cuban revolutionary hero who served as the country's first president in arms in 1868. Cespedes, a Cuban plantation owner, emancipated his slaves and issued the Declaration of Cuban Independence in 1868, kicking off the Ten Years' War (1868–1878). This was the first of three independence wars, the third of which, the Cuban War of Independence, ended Spanish authority in 1898 and resulted in Cuba's independence in 1902. He is revered in Cuba as the "Father of the Fatherland" for his initiatives that led to the island's eventual independence.

Céspedes was a landowner and lawyer in eastern Cuba, near Bayamo, who bought La Demajagua, a sugar plantation, after returning from Spain in 1844. On October 10, 1868, he issued the Grito de Yara (Cry of Yara), declaring Cuban independence and kicking off the Ten Years' War. After ringing the slave bell, signaling to his slaves that it was time to work, they stood before him waiting for commands, and Céspedes stated that they were all free men and were invited to join him and his other conspirators in the battle against the Spanish government of Cuba. He is known as Padre de la Patria (Father of the Country). He was elected President of the Republic of Cuba in Arms in April 1869.

The Ten Years' War was the first major attempt to break free from Spain and free all slaves. The conflict was fought between two factions. Eastern Cuban tobacco planters and farmers, aided by mulattos and some slaves, fought against western Cuba's sugarcane fields, which required a large number of slaves, and the Spanish governor-army. general's Hugh Thomas summarized the battle as one between criollos (creoles born in Cuba) and peninsulars (recent immigrants from Spain).

Céspedes was overthrown in a leadership revolution in 1873. Because the new Cuban administration refused to allow him to go into exile and denied him an escort, Spanish troops assassinated him in a mountain refuge in February 1874. The war concluded in 1878 with the Pact of Zanjón, which included concessions such as the emancipation of all slaves and Chinese who had fought alongside the rebels, as well as no action for political violations, but no freedom for all slaves or independence. Although the Grito de Yara had not accomplished much, it had lighted a long-burning fuse. Its lessons would come in handy during the Cuban War of Independence.