Churchill spent time in a Prisoner of War camp

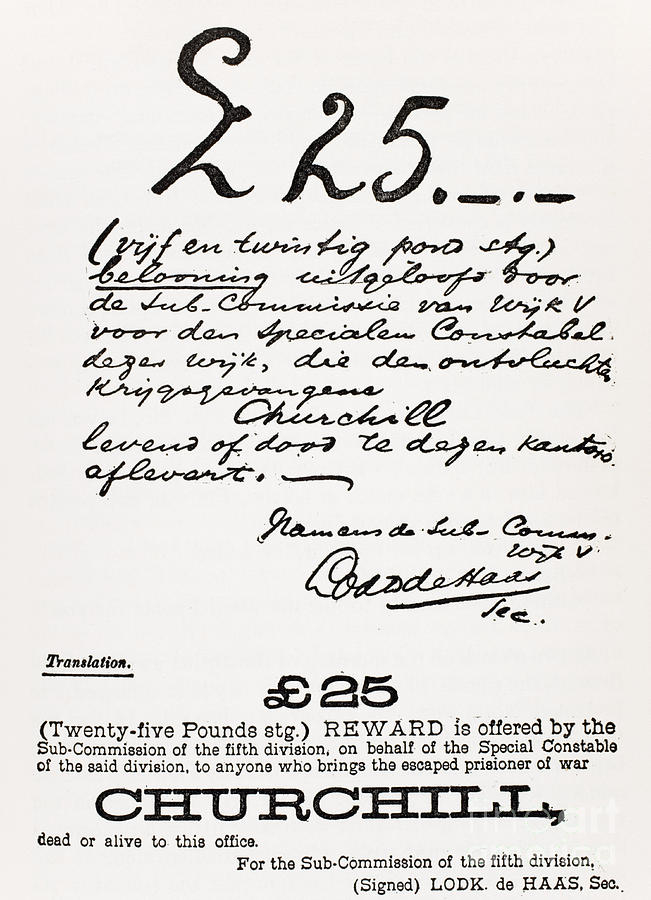

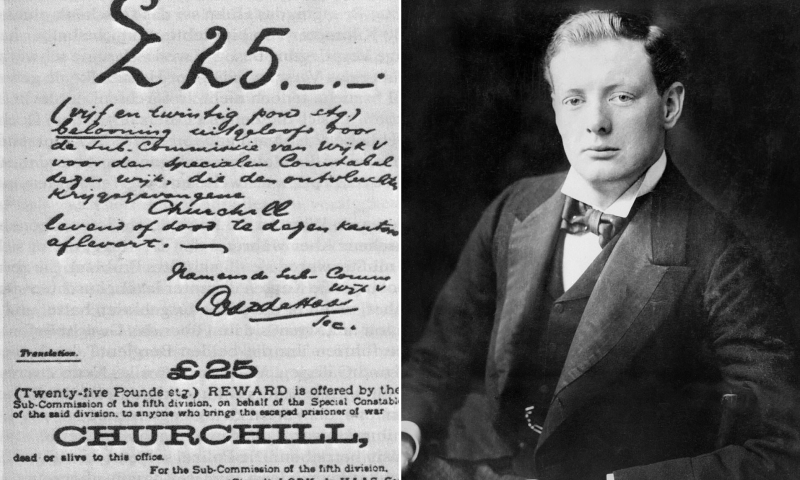

One of the other interesting facts about Winston Churchill is Churchill spent time in a Prisoner of War camp. The story begins when Churchill took a leave of absence from the army following his graduation from Sandhurst to visit Cuba and cover an insurrection there for a London newspaper. Later, he worked in India, Sudan, and South Africa as a war journalist and military officer, roles that were then legal. His armored train was attacked by Boers, the sons of Dutch settlers who were at war with the British at the time when it arrived in South Africa in 1899. Churchill was apprehended and sent to a prison camp, where he quickly escaped by climbing a wall at night as two of his fellow inmates turned around. Churchill scaled the prison wall and fled on the night of December 12, 1899, while the guards weren't looking. With no map, no knowledge of the local language, and only "four slabs of melting chocolate and a crumbling biscuit" in his pocket, the fugitive was still confident that he could make the 300-mile journey through the hostile territory without getting lost. This confidence was on a par with superhuman levels.

Churchill traveled by hiding during the day and drinking from streams when walking at night. When he was on the verge of being hungry, the fugitive took a gamble and knocked on the door of a coal mine boss. Once more, young Churchill's good fortune was on his side since John Howard, an Englishman, answered the door. Before Howard was able to sneak his countryman aboard a freight train that brought him to freedom in Portuguese East Africa, he spent days hiding in the complete darkness of the coal mine with only the patter of the rats darting around his pillow for company.

Churchill chose to continue reporting the war—and participating in it as well—despite having finally found the glory he had long desired. A bullet that struck him at the Battle of Spion Kop cut a feather from his cap. Churchill entered Pretoria on horseback after it was overrun in June 1900 and oversaw the release of the 180 men who were still imprisoned there. That summer, Churchill returned to Britain as the imperial hero he had always envisioned himself to be.