He didn't profit from the cotton gin despite its significance

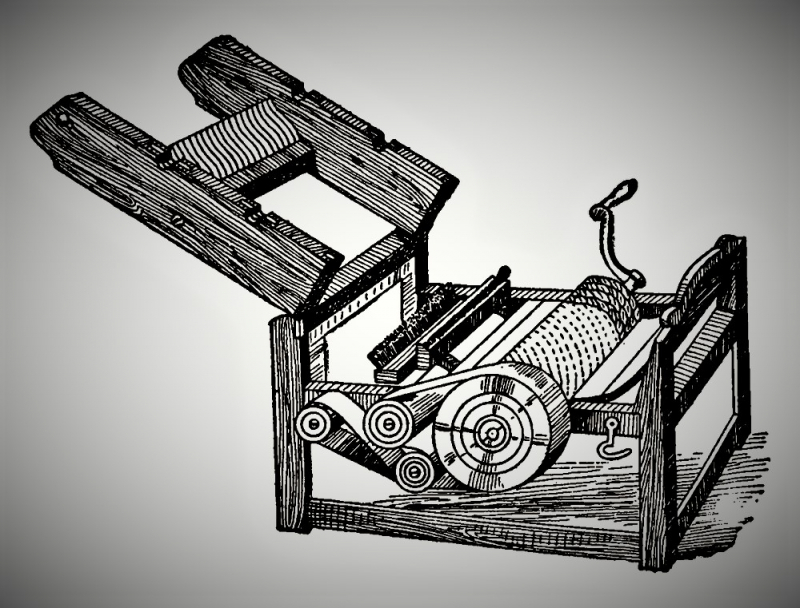

One of the most interesting facts about Eli Whitney is that he didn't profit from the cotton gin despite its significance. On October 28, 1793, Whitney submitted a patent application for his cotton gin. On March 14, 1794, the patent was granted, although it wasn't valid until 1807. The gins were not intended for sale by Whitney and his business partner Miller. Instead, they anticipated charging farmers for cleaning their cotton, two-fifths of the value paid in cotton, just like the owners of grist and sawmills. Infringement was unavoidable due to resentment about this plan, the device's simplicity mechanically, and the primitive state of patent law. Whitney and Miller were unable to produce enough gins to satisfy demand, thus gins from other producers were ready for sale.

A patent that was later revoked was given to Hogden Holmes in 1796 for a cotton gin that used circular saws instead of spikes. Ultimately, patent infringement lawsuits ate up the revenues, and their cotton gin company failed in 1797. One sometimes neglected fact is that Whitney's initial design had flaws. There is strong evidence that his sponsor, Mrs. Greene, fixed the architectural problems, but Whitney offered her no public credit or recognition.

Following the patent's approval, the South Carolina legislature approved $50,000 for those rights, while North Carolina imposed a licensing tax for five years, with a profit of roughly $30,000. A claim states that Tennessee may have paid $10,000. Whitney's cotton gin did not bring him the wealth he desired, but it did make him famous. Some historians have suggested that Whitney's cotton gin was crucial to the American Civil War's inadvertent cause. Whitney's innovation led to a revival of the plantation slave trade, which ultimately resulted in the American Civil War.