Louis Braille was very talented at music

From the beginning of his studies at the Institute (the Institut Royales des Jeunes Aveugles), Braille excelled in music, taking home the top medal for solo cello in his fifth year. At that point, Braille's standing as a musician had already been cemented. He performed in several Parisian parishes, notably Notre-Dame-des-Champs and Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs, which possessed a beautiful old organ. He made spare change tuning pianos in and around Coupvray over the summer. When one of his exceptionally gifted students was going to depart the Institute without a job in 1839, Louis extended to him an offer of his position at Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs.

Even Braille's pupils had urged him to figure out how to make his simple raised-dot method work with music. The 18th-century composer Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778)'s technique, which the Institute had accepted to replace Haüy's system, served as the foundation for his first music code. Rousseau's music, however, had two very significant flaws: it depended on embossed print, and it was unable to convey the relative values of musical notes.

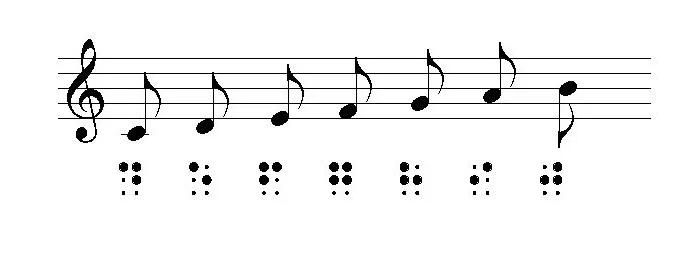

Rousseau's method was first enhanced by Braille by substituting his own six-dot Braille code for the difficult-to-read embossed print. Unexpectedly, Braille's straightforward cell handled every facet of music.

He created the fundamental musical code in 1834, from which blind musicians today have developed a complex system. His musical notation technique was so excellent that it was adopted almost immediately, in contrast to Braille's literary code, which took decades to achieve recognition. It is hard to speak of Braille's code in terms of music with too much adulation, a music instructor at the Missouri Institution for the Education of the Blind claimed in 1866.