Mandela saw national reconciliation as the most important mission of his precidency

Mandela saw national reconciliation as the most important mission of his presidency as he presided over the transition from apartheid minority rule to a multicultural democracy. After witnessing the devastation caused by the departure of white elites in other post-colonial African nations, Mandela attempted to reassure South Africa's white people that they were safe and well-represented in "the Rainbow Nation." Although the ANC would dominate his Government of National Unity, he attempted to build a broad coalition by nominating de Klerk as Deputy President and other National Party leaders as Ministers of Agriculture, Environment, and Minerals and Energy, as well as Buthelezi as Minister of Home Affairs. The remaining cabinet positions were filled by ANC members, many of whom had long been Mandela's comrades, such as Joe Modise, Alfred Nzo, Joe Slovo, Mac Maharaj, and Dullah Omar, while others, such as Tito Mboweni and Jeff Radebe, were much younger.

Mandela personally met with apartheid regime figures such as lawyer Percy Yutar and Hendrik Verwoerd's widow, Betsie Schoombie, and laid a wreath beside the statue of Afrikaner hero Daniel Theron. He declared that "courageous people do not fear forgiving, for the sake of peace," emphasizing personal forgiveness and reconciliation. As South Africa hosted the 1995 Rugby World Cup, he pushed black South Africans to rally behind the hitherto despised national rugby side, the Springboks. Mandela wore a Springbok shirt in the final versus New Zealand, and when the Springboks triumphed, Mandela delivered the trophy to Afrikaner captain Francois Pienaar. This was widely regarded as a significant step forward in the reconciliation of white and black South Africans. Mandela's efforts at peace assuaged white people's anxieties while also drawing criticism from more militant black people.

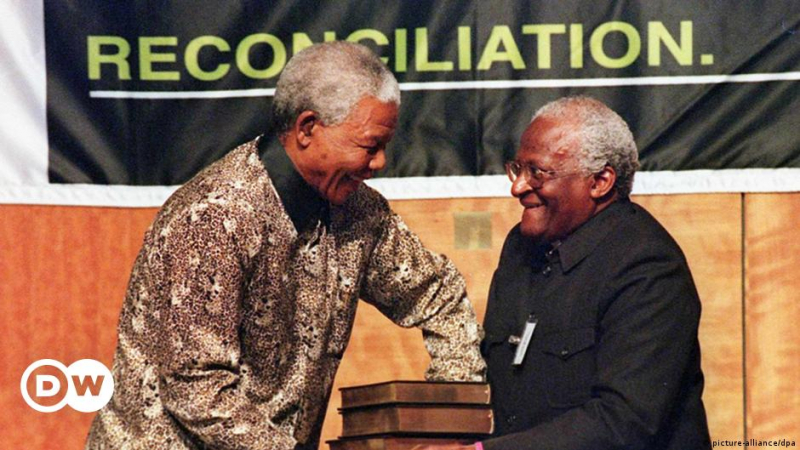

Mandela oversaw the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, chaired by Tutu, to investigate crimes perpetrated by both the government and the ANC under apartheid. To avoid the creation of martyrs, the Commission gave individual amnesties in exchange for testimony about apartheid-era crimes. It was established in February 1996 and conducted two years of hearings on rapes, torture, bombings, and assassinations before presenting its final report in October 1998. Both de Klerk and Mbeki filed appeals to have portions of the report hidden, but only de Klerk's was successful. Mandela applauded the commission's work, saying it "had helped us move away from the past to concentrate on the present and the future".