Shenyi

The shenyi was a single long robe, as opposed to a top and bottom. The shenyi's structure, however, consists of two parts: a yi (the upper garment) and chang (the lower garment), which are joined to create a single robe. The paofu is a one-piece robe with the lower and upper parts cut from a single piece of fabric; the shenyi differs structurally from this garment. Additionally, a typical shenyi was constructed with twelve cloth panels that were stitched together.

The shenyi and its components existed prior to the Zhou period, having initially appeared during the Shang dynasty. People of the Shang and Western Zhou eras, on the other hand, wore a set of clothing known as yichang, which consisted of a jacket called yi and a long skirt called chang. The yi and chang were sewed together to form a robe for convenience; this combination resulted in the shenyi, which was produced during the Zhou period. From the Zhou through the Han dynasties, the shenyi became the primary form of Hanfu robe, remaining popular. The loose shenyi with wide sleeves was popular among the aristocracy, elites, and members of the royal families from the Spring and Autumn period through the Han dynasty. The loose shenyi was made for the top echelons of society, particularly for ladies who desired to avoid showing off their body parts when walking. It wrapped around the body from front to back and lacked a front-end slit. In a time when the kun was not yet widely accepted by the populace, the design of this wrap-style shenyi was crucially necessary. The aristocracy's obsession with layered, loose-fitting clothing also demonstrated their desire to set themselves apart from the laborers and served as a marker of their high rank. The shenyi had evolved in forms by the Han dynasty; it then further developed in the Han dynasty, with subtle differences in styles and shapes appearing. Following the Han dynasty, the shenyi declined in favor until it was restored during the Song dynasty.

The Western Zhou dynasty had tight norms and regulations governing its citizens' daily apparel based on their social position; these regulations also covered the material, shape, sizes, colors, and decorative patterns of their garments. The Zhou dynasty's hierarchical system based on social status, gender, age, and situation also influenced the shenyi. Despite these complex regulations, the shenyi remained a basic form of garment that served the needs of all classes, from nobles to commoners, old to young, men to women; and people would thus express their identities on their outer garments through recognizable objects, decorations, colors, and materials. Nobles wore an ornamented coat over the shenyi, whereas commoners wore it alone.

There were still stringent laws and norms governing the attire of all social groups throughout the early Eastern Zhou dynasty, which were designed to preserve social differentiation between members of various classes.

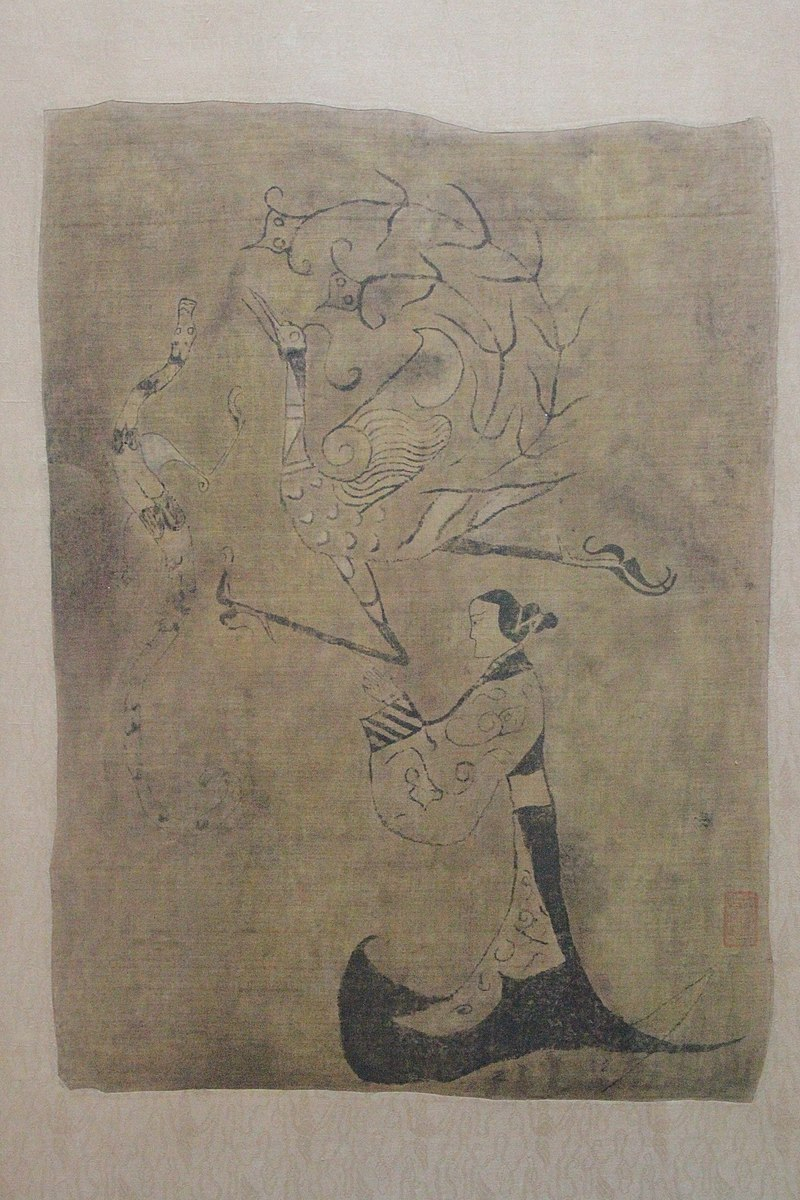

The shenyi was a moderately formal style of attire during the Warring States period. The front of the shenyi, which represented the Warring States Period, was designed to be stretched and wrapped around the torso numerous times. The Silk painting depicting a man riding a dragon and the Silk painting with the female figure, dragon, and phoenix designs both show wrapping-style shenyi for men and women. Both paintings were discovered in a Chu tomb during the Warring States period (5th century BC), in Changsha, Hunan Province.

During this time, linen was frequently utilized as a material, but when shenyi was fashioned into ceremonial clothing, black silk was used instead. Given that it was both practical and basic in design, it was worn by both the literati and the soldiers. The dadai or shendai silk ribbon, on which a decorative item was fastened, was also used to tie the shenyi in the front, just below the level of the waist.