The fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also known as the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire's vast territory was divided into several successor polities as a result of the Empire's failure to enforce its rule. The Roman Empire lost the strengths that had allowed it to exercise effective control over its Western provinces; modern historians attribute this to factors such as army effectiveness and numbers, Roman population health and numbers, economic strength, emperor competence, internal power struggles, religious changes of the period, and civil administration efficiency. Increasing pressure from invading barbarians outside of Roman culture also played a significant role in the downfall. Many of these immediate elements were influenced by climatic changes as well as endemic and pandemic diseases. The causes of the collapse are key issues of ancient world historiography, and they inform much of modern discourse on state failure.

In 376, an uncontrollable influx of Goths and other non-Romans escaping the Huns reached the Empire. After winning two catastrophic civil wars, Theodosius I died in 395, leaving a failing field army and the Empire, still troubled by Goths, divided between his two inept sons' fighting ministers. Further barbarian clans crossed the Rhine and other borders and were not destroyed, expelled, or subjugated, as the Goths were. The Western Empire's armed forces became sparse and inefficient, and despite brief recoveries under capable leaders, central power was never effectively consolidated.

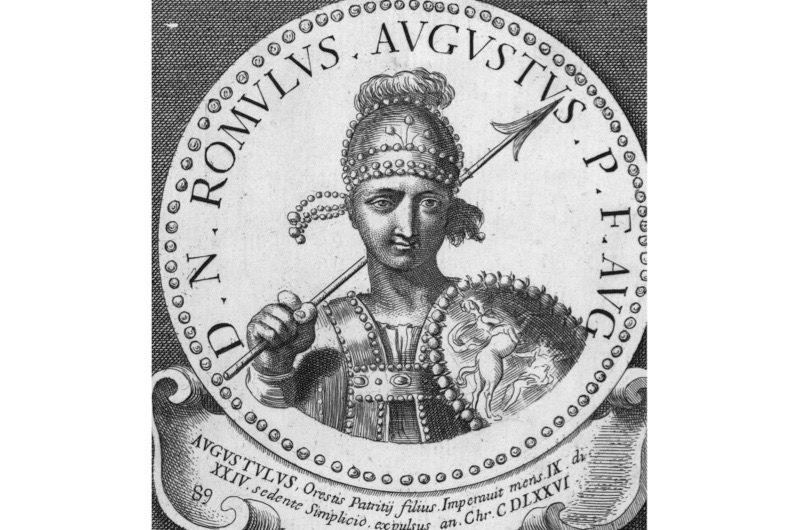

By 476, the Western Roman Emperor held little military, political, or financial power, and had no effective control over the scattered Western territories that might still be regarded as Roman. Barbarian nations had established their own power across most of the Western Empire's territory. The Germanic barbarian ruler Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustulus, the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire in Italy, in 476, and the Senate transmitted the imperial insignia to the Eastern Roman Emperor Flavius Zeno.

While its legitimacy survived for centuries longer and its cultural influence is still felt today, the Western Empire was never able to rise again. The Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire survived and, despite its diminished strength, remained an effective power in the Eastern Mediterranean for centuries.

While the loss of political unity and military power is unanimously acknowledged, the Fall is not the sole unifying notion for these events; the late antiquity period highlights the cultural continuities that existed throughout and beyond the political collapse.