The Stamp Act of 1765

Between 1756 to 1763, the Seven Years' War was fought between a British-led alliance and a French-led coalition. Around the same period in America, the French and Indian War erupted, pitting British territories in America against New France, a region occupied by France. Even though the British won both wars, they did so at a tremendous cost. By taxing the Thirteen Colonies in America, Britain attempted to recover the expense of its standing army in America as well as reduce its financial burden.

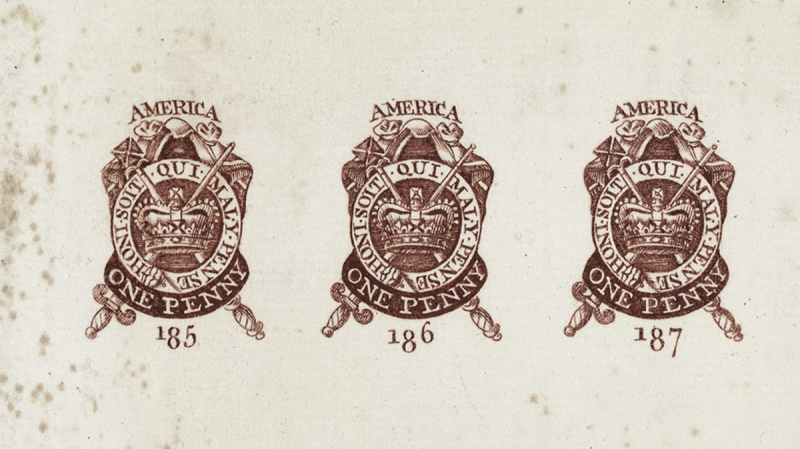

The Stamp Act of 1765 was approved by the British Parliament in March of that year. This was the first time the colonies were subjected to direct British taxation. Many printed materials, including legal documents, periodicals, newspapers, and even playing cards, were required to be printed on London-stamped paper with an embossed revenue stamp under the Act. The colonists objected to the taxes not because they were excessive, but because they were imposed by a British Parliament that they had no representation. One of the main grounds of contention between colonists and Britishers was the issue of "no taxation without representation."

Prominent figures such as Benjamin Franklin and members of the Sons of Liberty, an independence-minded society, contended that the British parliament lacked the jurisdiction to levy an internal tax. The resulting violence drew widespread attention as a result of the public outcry. Threats were made against tax commissioners, and some of them resigned out of fear; others just failed to collect any money. The "Stamp Act would have to be implemented by force," Franklin wrote in 1766. Parliament, unable to do so, repealed the Stamp Act a year later, on March 18, 1766. The seeds of strife that would lead to the major events of the American Revolution, on the other hand, had been sowed.

Date: March 22, 1765