There were more deserters at Valley Forge than at any other period during the Revolution

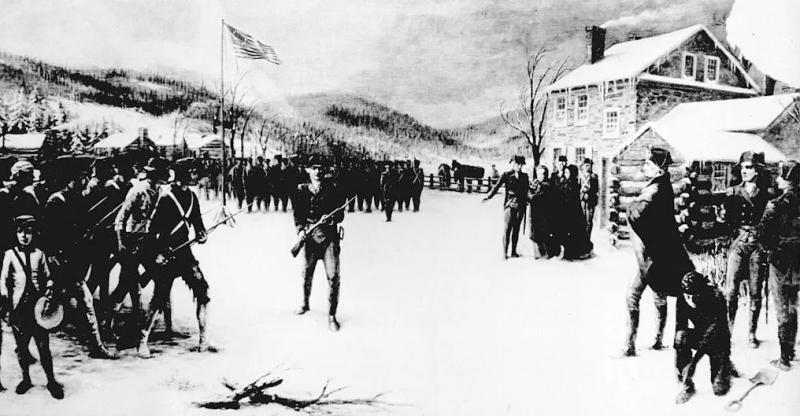

Before even reaching the winter encampment, Washington was already vociferously complaining to his brigadiers about the number of “summer soldiers” simply vanishing from his army’s ranks. Once the encampment was established, those desertions multiplied daily, reaching such epic proportion that the commander-in-chief was forced to issue a series of General Orders threatening his junior officers with dismissal if they failed to convene multiple daily roll calls – the only way, he felt, to ensure that men abandoning their posts could not get too far before specially-designated mounted units could round them up and return them. Yet despite the most recidivist offenders being hanged in the camp’s parade grounds, still they left Valley Forge.

It was not unusual for regimental commanders to find scores of grumbling soldiers outside their huts threatening to desert en masse “for want of victuals.” Loyalist spies stationed along the Hudson Highlands spotted so many New Englanders simply walking home that they (mistakenly) warned the British in New York that the Continentals might be massing for a rearguard surprise attack on the city. “The spirit of desertion never before rose to such a threatening height as at the present time,” an alarmed Washington wrote to the Continental Congress. Come the spring of 1778, the combination of death and “self-granted furloughs” had reduced the commander in chief’s force to barely 8,000 able-bodied men.