Top 10 Body Parts with Stories to Tell

When someone passes away, there are typically many alternatives for how to appropriately and respectfully dispose of their remains. Although the techniques ... read more...vary, they all typically deal with the entire body at once. But it doesn't always work out like that. For preservation purposes, some body parts are occasionally removed. Sometimes they inexplicably disappear, especially when it involves a notorious or well-known person. Today, Toplist has looked at ten such body parts that have fascinating backstories to share about what happened to them after their owners passed away.

-

How did Napoleon's penis end up in New Jersey? That is a strange and twisted story, one with many unanswered questions. During the autopsy, it appears that his doctor, Francesco Autommarchi, severed the "little general" and delivered it to the priest who performed his last rites, Abbé Anges Paul Vignali.

People don't know the "tendon's" precise movements after it left the Vignali family until it entered American rare book dealer A.S.W. Rosenbach's collection in the early 20th century. The organ was on show at the Museum of French Art in New York for the first and only time ever in 1927. After that, its history becomes a little more hazy once more until 1977, when urologist Dr. John Lattimer paid $3,000 for it at auction. For many years, he kept it at his New Jersey home, only letting a select few people see it.

The member is currently in the care of Lattimer's heirs, who likewise closely guard it. In addition, it has been described as being "extremely little," "withered," and "like a piece of leather or a shriveled eel" in case you were curious about what it looks like.

https://popularhistoria.se

https://whfpdubai.com/ -

In addition to being the creator of utilitarianism and one of the founders of University College London (UCL), Jeremy Bentham is best known today as the man who requested that his body be dissected, preserved, and displayed as a "auto-icon."

Bentham, strangely enough, was granted his wish. Dr. Thomas Southwood Smith removed Dr. Jeremy Bentham's skeleton after his death in 1832 and dressed it in Bentham's attire. The auto-icon was then displayed inside the UCL student center and served as the school's unofficial mascot.

The head was a different story. Dr. Smith wasn't exactly a specialist on mummification, but Bentham insisted that they use his own mummified head. The college decided to replace it with a wax replica despite his best efforts because the final product was horrifying. The real head was still on exhibit for the majority of the auto-existence, icon's sitting at its previous owner's feet. After being taken and destroyed during a prank, the real head wasn't kept in a safe until the 1990s for security reasons.

The offenders were students from King's College, a school that competes with UCL. They allegedly stole Bentham's head in 1989 and used it as a football in a neighborhood game. By the time the college received it back, it was undoubtedly in poor shape, which is why UCL chose to remove it from the exhibit. However, the students weren't too put off. The wax head of Bentham was simply taken the following year.

https://www.thefamouspeople.com/

http://www.traveldarkly.com -

Famous composer Joseph Haydn from Austria passed away in Vienna in 1809. Given his stature and the support of the Royal House of Esterházy, he unquestionably deserved a sumptuous funeral. However, due to the fact that Austria was at war with France at the time, Haydn was promptly and quietly laid to rest.

Around ten years later, Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II was reminded that Haydn was still buried there, and the wealthy monarch had him dug up and moved to his family seat. Nevertheless, when he did, he saw that Haydn's head was gone.

This is what transpired. Haydn's head was sent to two fans of the composer shortly after his burial so they might use it for phrenology, the disproved quackery that used measurements of the bumps on the skull to forecast certain qualities. They retained the head as a trophy once they were finished. It was also displayed for anybody who came to visit, making it simple for the prince to identify the thief. They complied with his request to return the skull, sort of. They did bring back "a" skull, which was interred next to Haydn's ashes in a tomb.

Although people are unsure of whose skull it was, the cunning pair retained onto Haydn's for their own use. The skull was passed down from generation to generation over the years until it was acquired by the Esterházy family in the early 20th century. After 150 years of being separated, they finally organized a ceremony to join the body and the head. Haydn's grave now has two heads since they decided to leave the other skull there rather than just toss it out because they were unsure of its owner.

http://fixquotes.com/

https://www.austria.info -

Burke’s Skin is one of the top Body Parts with Stories to Tell. William Burke and William Hare are still among Scotland's most infamous murderers despite their murdering spree occurring almost 200 years ago. Burke and Hare started out as body snatchers, stealing fresh bodies to sell for anatomical dissections, but later realized it was quicker and more profitable to just make the corpses themselves. Before being discovered, they killed 16 people. When they were, Hare turned state's evidence and revealed his companion in return for immunity.

On January 28, 1829, William Burke was executed by hanging in front of a sizable throng that numbered in the tens of thousands. Burke received a public dissection as part of his sentence, and the Edinburgh Medical School's anatomical museum now houses his preserved skeleton. Strangest of all, though, was the excision of Burke's skin, which was eventually applied to a book to create a binding known as anthropodermic bibliopegy.

https://fineartamerica.com

https://www.nationalgalleries.org -

In a well-known moment from Hamlet, the main character picks up the skull of a deceased court jester and begins a monologue with the words, "Alas, dear Yorick! The man I knew, Horatio. Yorick was formerly performed by an actual human skull, and has since been referred to as "theatre's greatest skull." Based on diaries and lists of props from that time period, people believe this wasn't done during Shakespeare's lifetime, although it was common during the 18th and 19th centuries. People know this because numerous modern reviewers have mentioned the use of "actual skulls and bones" in the play in their notebooks and reviews.

What about in contemporary times? Peter Hall, the director of London's National Theater, allegedly planned to try it in 1975, but he was so overburdened during rehearsals that he substituted a replica for the live performances.

André Tchaikowsky, a pianist, left his head to the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1982, with the express purpose of being used as Yorick. His odd request was granted, and his skull was utilized for photo sessions and dress rehearsals but never on stage. Up until 2008, when David Tennant, the Doctor, performed Hamlet on the show with a real skull.Del Close, an American comedian and acting instructor, had the same thought. His will left his skull to the Goodman Theater in Chicago, where it is now utilized as Yorick. He passed away in 1999. Despite the fact that an actual cranium was used on stage, rumors that it did not belong to Del Close quickly spread. The executor of his estate initially refuted the accusations, but she later admitted to buying a substitute skull from a medical supply firm since she was unable to locate someone to preserve the original skull before the cremation.

http://medyamagazine.com/

https://www.chicagotribune.com -

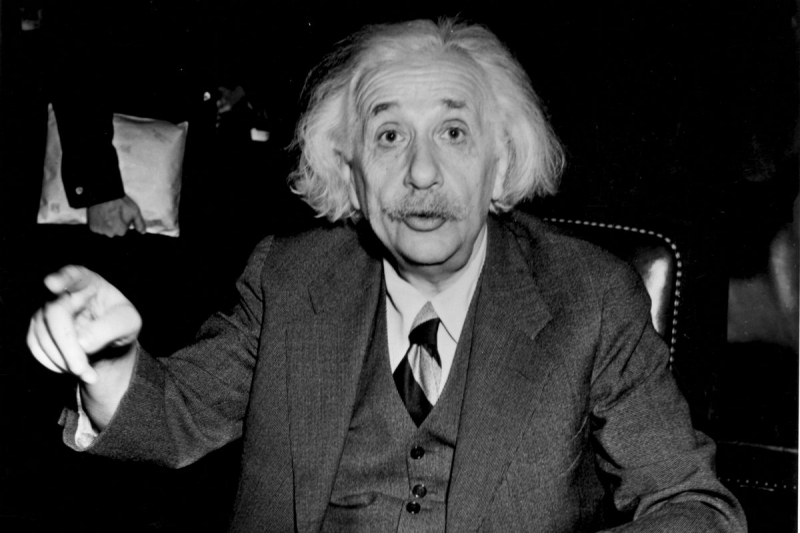

Albert Einstein's brain underwent a similar predicament following his passing in 1955. Thomas Harvey, a pathologist, took care of his body and then removed the brain for study. It's not unexpected that people were interested in studying Albert Einstein's brain given that the name "Einstein" has come to be associated with "genius." This narrative is contentious because it is still unknown if Harvey had authorization to act as he did or whether he merely took Einstein's brain and refused to give it back.

Einstein had instructions for his corpse to be incinerated and his ashes to be spread in a secret place, according to the scientist's biographers. Naturally, Harvey was unaware of any of this and was just interested in the possibility to further his own career. When Einstein's son Hans Albert learned about it, he was incensed, but Harvey was able to persuade him to let him keep the brain so he could research "the secret of genius," with the condition that he would publish his results as soon as possible in academic publications.

However, the years stretched into decades and nothing changed. Everyone ultimately forgot about Einstein's brain, but Harvey kept hold of it, transporting it across the country in numerous mason jars. Although it wasn't known at the time, Harvey's silence over those years was due to the lack of anything to say. Harvey didn't want the findings of the numerous neurologists and neuropathologists who examined the tiny samples he was willing to share to be made public because they all concluded that the brain was normal.

The first articles on Einstein's brain, asserting numerous differences between his brain and an ordinary one, which could have highlighted the traits of brilliance, didn't come out until 1985, three decades after Einstein's passing. Although many people attacked and refuted these works, Harvey retained his brain. He had already lost his marriage, his job, and his career at that point, leaving him with nothing but his wits. After Einstein passed away, his heirs finally donated his brain, the most of which was donated to the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

https://www.dukebasketballreport.com/

https://www.earth.com/ -

A body discovered in a Danish bog in 1950 came to be known as the Tollund Man. He was in outstanding shape considering his age—roughly 2,400 years—especially the head, which still had hair and beard stubble evident. The head was saved, but the rest of the corpse was left behind because extracting the body from the bog intact was a challenge that scientists weren't up to 70 years ago. So, if you ever visit the Silkeborg Museum and witness the Tollund Man, be aware that the body is a reproduction while the head is the real deal.

What transpired to the genuine body, then? It was dug out of the bog as carefully as possible, autopsied, and split up into smaller parts that were distributed for studies all around the world. Since the head was unquestionably the collection's focal point, no one paid close attention to the other components, and soon enough, they began to go missing.

In the 1980s, academics proposed that they might want to try putting the body together. Everything was recovered after years of work, with the exception of the internal organs and the right foot's big toe, which was obviously sawed off.

After another several decades, the museum received an intriguing contact from Birte Christensen in 2016, who claimed to be the owner of the Tollund Man's big toe. She was the descendant of the late conservator Brorson Christensen, who assisted in keeping the Tollund Man's head intact. He sliced off the toe to examine various preservation methods while working on the bog body. He simply kept it in a jar of blue liquid on his desk till he passed away because no one ever requested for it back.

https://strangebtrue.blogspot.com/

https://www.pinterest.jp/ -

André Bessette, often known as Brother André, rose to prominence in the Canadian Catholic Church in the early 20th century. He was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1982 and later declared a saint in 2010. However, all of this occurred several years after his passing. Brother André passed away in 1937, and his heart was immediately taken and placed inside a reliquary that was displayed at St. Joseph's Oratory in Montreal. The heart was taken in 1973 and kept for a $50,000 ransom. Rewind a few decades.

The heart was thought to be lost for a year because no ransom was paid. Then, in 1974, a well-known Montreal attorney named Frank Shoofey got a call from an unknown caller claiming to know where Brother André's heart was. Shoofey and several other police officers went to the basement of an apartment building in the city as per his directions and discovered the reliquary concealed inside a locker, with the seal intact and the heart in tact. What caused the thief's change of heart—pun clearly intended—also remains a mystery, as does his identity.

http://hannahstears.net/

http://www.todayscatholicnews.org -

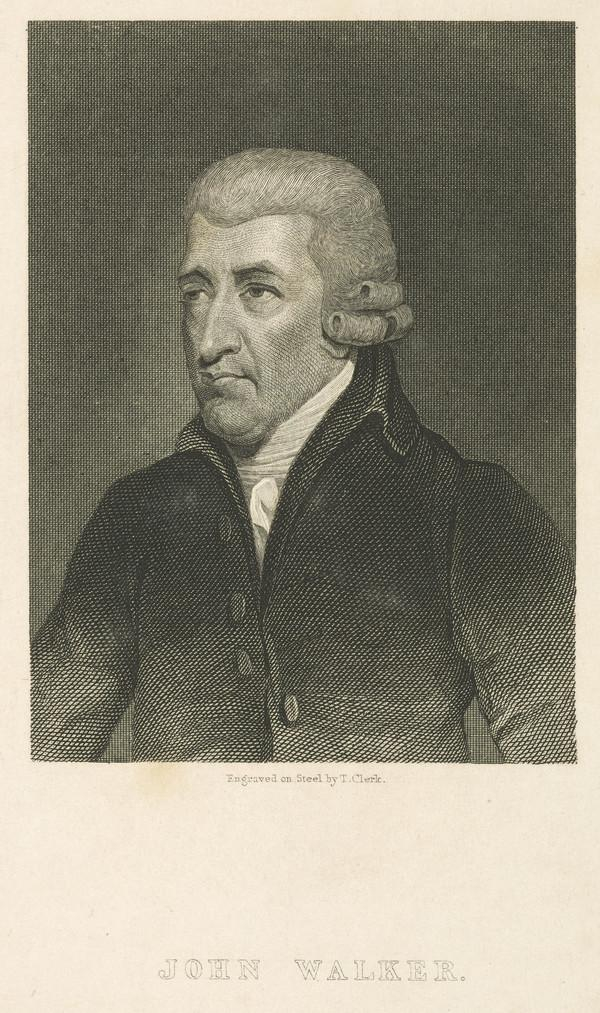

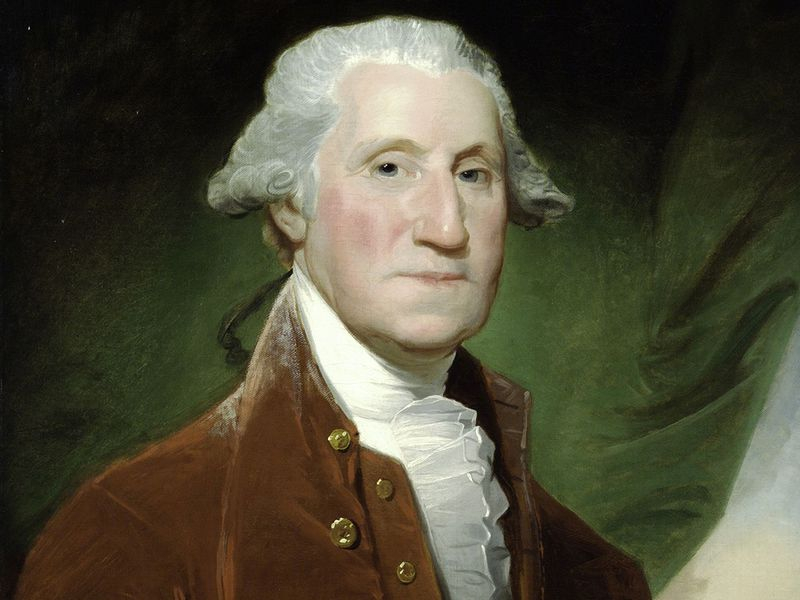

Dental issues with George Washington have been fairly well documented. He first experienced toothaches and decay in his 20s, and as he aged, the problems only grew worse, giving him constant anguish and necessitating the use of many dentures. Contrary to popular belief, none of them were made of wood. In reality, Dr. John Baker constructed Washington's first set of dentures out of ivory before the Revolutionary War.

After that, Washington used the services of a French dentist by the name of Jean-Pierre Le Mayeur; nevertheless, John Greenwood eventually took over as the Founding Father's personal dentist.

When Washington was elected president, he only had one last natural tooth, and Greenwood did everything in his power to preserve it by including a space for it in every set of dentures he created for the president. In addition to Greenwood's conviction that a tooth should never be extracted while it can still be kept, this was also for practical reasons because the genuine tooth served as the anchor for the dentures.

But finally, it was inevitable, and Washington also lost his final tooth, which he gave to John Greenwood as a thank-you gift. The particular locket that Greenwood always wore and kept the tooth in is currently in the collection of the New York Academy of Medicine.

http://commons.wikimedia.org

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/ -

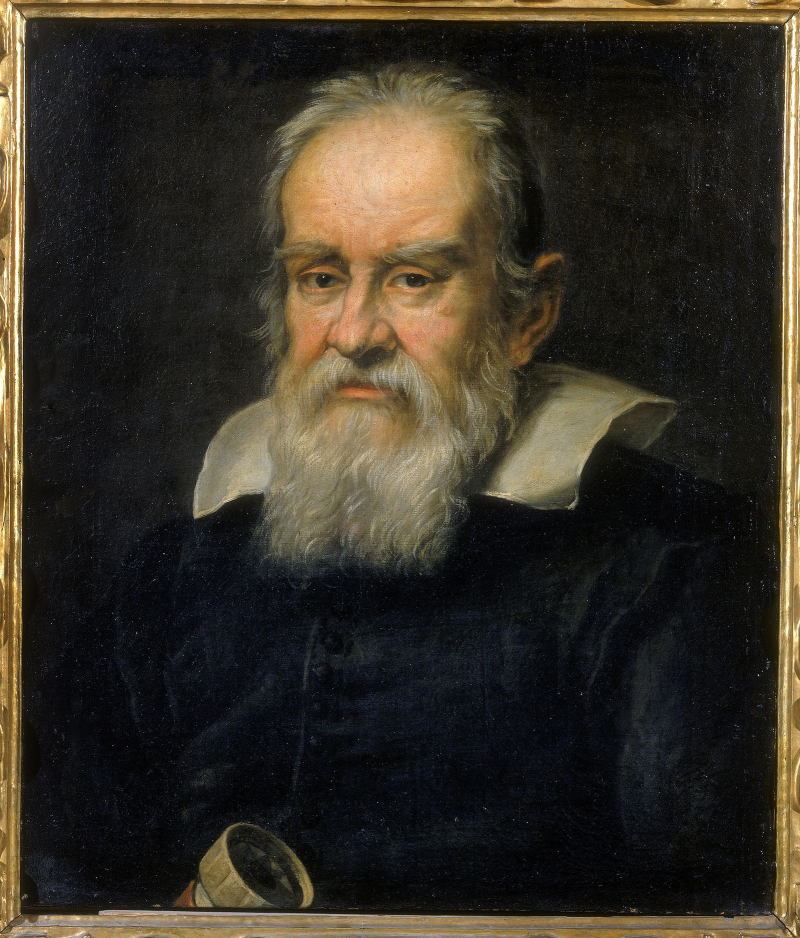

Few, if any, Italian scientists were more productive or significant than Galileo Galilei, an astronomer who clashed with the Catholic Church over his erroneous heliocentric theories. Many of the items he used to make his findings are still on display at the Galileo Museum in Florence, which was formerly known as the Institute and Museum of the History of Science. His middle finger, which is protected by a glass egg, is also visible.

Where did it come from? So, nearly a century after Galileo's passing, in 1737, some of the scientist's admirers organized for his body to be exhumed and buried in a tomb more appropriate for someone of his status. Since they were already there, they also removed three of Galileo's fingers so they could be kept as souvenirs along with his final tooth.

After being preserved by Florentine antiquarian Anton Francesco Gori, the middle finger was eventually sold to a number of academic institutions before being acquired by the Museum of the History of Science in 1927. Since then, it has been on display as the sole set of human remains to be found in a museum featuring scientific apparatus.

At least, it was until 2009, when the tooth and the other missing digits reappeared after nearly 300 years. They were separated from the middle finger, sold at auction, and are currently on exhibit together.

https://www.thoughtco.com/

https://easyscienceforkids.com/