Top 10 Facts About The Battle of Franklin

The Battle of Franklin was fought between the American Army and the Confederate States Army in Franklin, Tennessee, as part of the Franklin–Nashville Campaign ... read more...of the American Civil War. It was "one of the worst disasters of the war for the Confederate States Army". These are some of the facts about this special event in the American Civil War that your might not know.

-

After being informed that Union general William Sherman will turn east in his “March to the Sea" after taking up Atlanta, Confederate general John Bell Hood led the Army of Tennessee north out of Georgia and towards the supply and communications hub of Nashville, Tennessee, aiming to draw Sherman into a fruitless pursuit before swinging through Kentucky and joining Robert E. Lee in Virginia with a legion of new recruits and cartloads full of Yankee food and munitions. John Bell Hood (June 1 or June 29, 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. During the Battle of Franklin, he stood against William Sherman and John Schofield. Although brave, Hood's impetuosity led to high losses among his troops as he moved up in rank.

General John Schofield, commanding Sherman’s rearguard, parried Hood’s thrusts in a series of small engagements as both forces raced toward Nashville. Hood’s hopes for a decisive campaign lay on defeating Schofield before the Union general reached the city, where another 25,000 Federals under General George Thomas waited. Hood caught Schofield at Franklin on November 30, 1864, about twenty miles south of Nashville. As the sun began to set, Hood ordered an attack. This attack causes casualties for both sides, and the attack did not work out well on John Bell Hood's side.

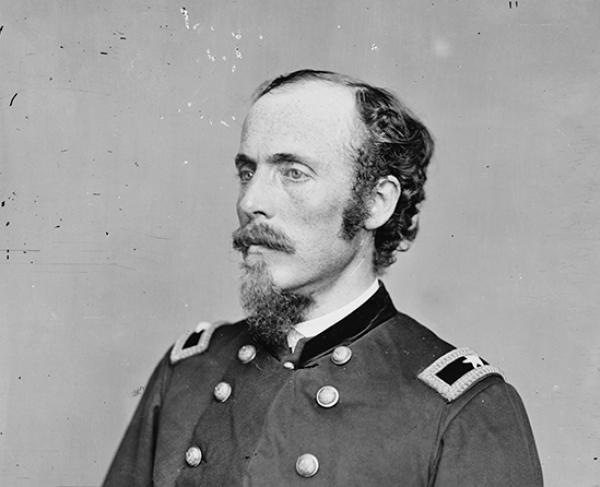

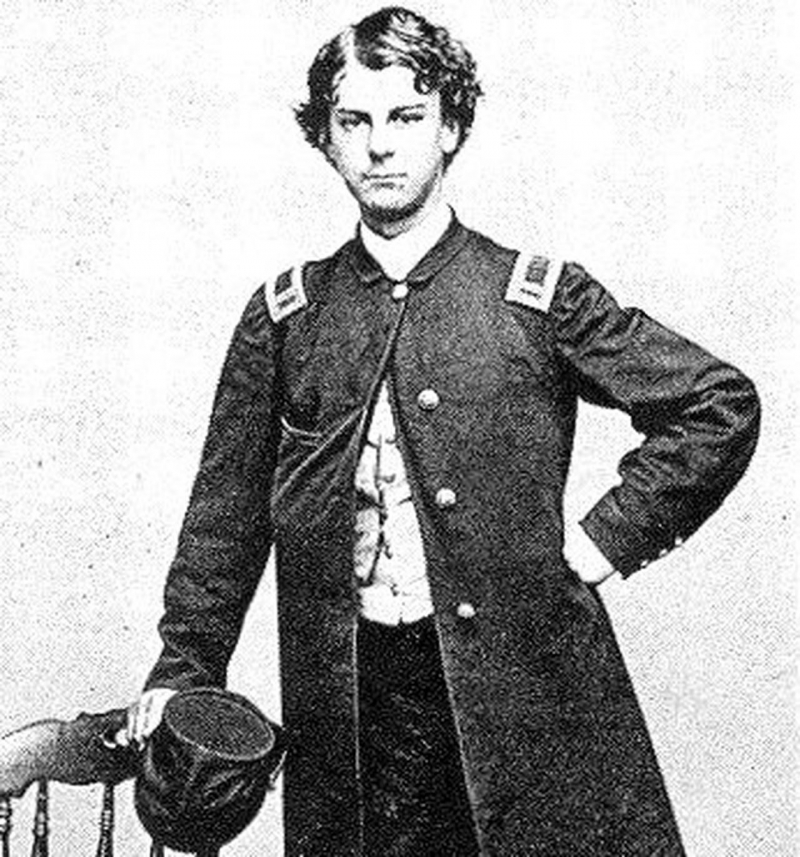

John Bell Hood - Photo: www.battlefields.org

Photo: warfarehistorynetwork.com -

John McAllister Schofield (September 29, 1831 – March 4, 1906) was an American soldier who held major commands during the American Civil War. He took an important role in the Battle of Franklin. At Columbia, Tennessee, he had prevented Hood from crossing the Duck River for five days. When Confederates began to assemble for battle on the southern bank of the Duck on the 29th, Schofield felt it was time to withdraw. He sent half of his army twelve miles north to Spring Hill while the other half remained to cover the river crossing. But Schofield had been fooled. The grey mass opposite Columbia was a diversion. While their comrades occupied Schofield’s attention, two Confederate divisions crossed at a ford further east and swung around the city to land astride the north-south road connecting Columbia to Spring Hill. The Union force was divided and in grave danger.

Command confusion disrupted several Confederate attacks in what became known as the Battle of Spring Hill, preventing a decisive interdiction of the Federal escape route. That night, soldiers and wagons evacuating Columbia passed within earshot of the Confederates encamped along the road, but the attack that might have changed the course of the campaign never came. The next day, Hood, “wrathy as a rattlesnake,” accused the Army of Tennessee of cowardice and ordered a pursuit of Franklin. The failure of the day before had prevented a battle to the Southerners’ advantage and sealed the violent fate of thousands.

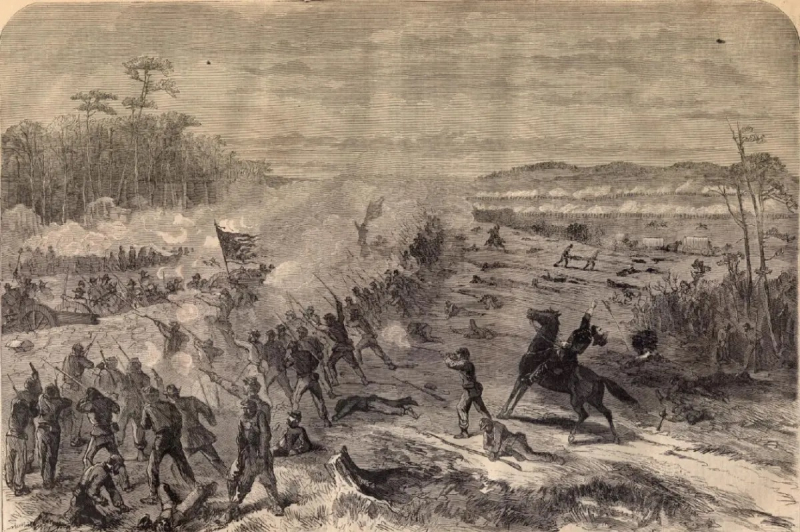

The Battle of Spring Hill - civilwarmonths.com Video: American Battlefield Trust -

Samuel Emerson Opdycke (January 7, 1830 – April 25, 1884) was a businessman and Union Army brigadier general during the American Civil War. During the Battle of Franklin, Emerson Opdycke led a brigade in George Wagner’s division. As the Confederates approached, Wagner ordered Opdycke to join his fellow brigade commanders, John Lane and Joseph Conrad, in a line thrown out half a mile in front of the Union breastworks.

Recognizing the folly of taking such an exposed position in front of a vastly superior force, Opdycke vehemently refused to obey Wagner’s directive and instead deployed his brigade about two hundred yards behind the Carter House. Although he was mainly looking for a good place to cook breakfast, from this spot he could also quickly reinforce any threatened point in the Union center. When Wagner’s position was shattered and his men were hurled back through the main line, the Confederate attackers secured a dangerous foothold in the maelstrom around the Carter House. Opdycke threw his men into the fray. The Confederates could advance no further, and after hours of bloody combat, the line was finally stabilized. Had Opdycke obeyed Wagner’s orders, his command would have surely been routed along with the rest of the division, and Hood’s army may well have shattered the unsupported main line.

Samuel Emerson Opdycke - www.battlefields.org

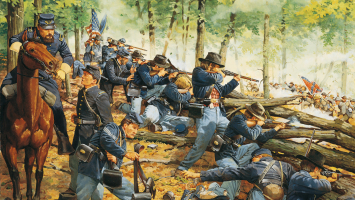

Opdycke on the battlefield - fineartamerica.com -

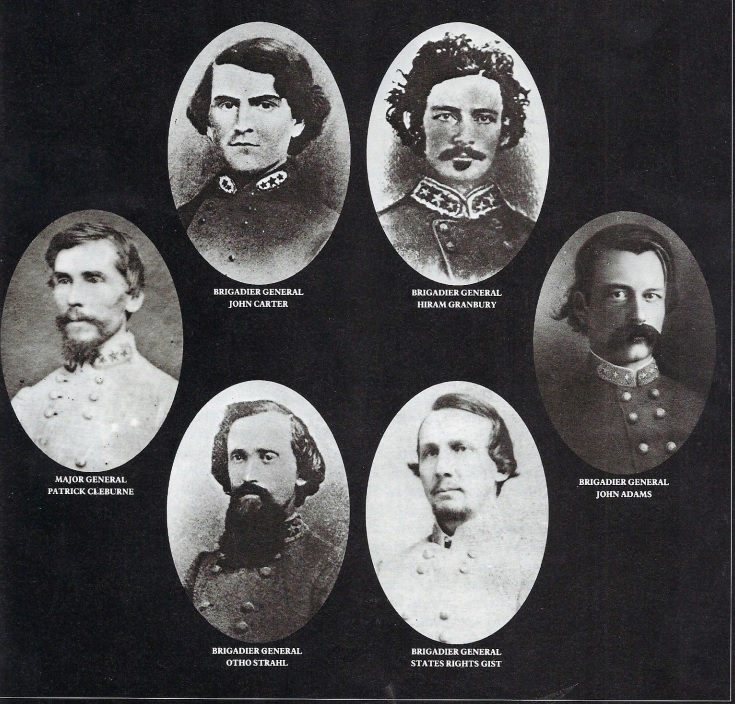

The Battle of Franklin ended with the Union victory, as the Union's losses were reported as only 189 killed, 1,033 wounded, and 1,104 missing. On the other hand, the Confederates suffered 6,252 casualties, including 1,750 killed and 3,800 wounded. An estimated 2,000 others suffered less serious wounds and returned to duty before the Battle of Nashville. However, the devastating defeat of Gen. John Bell Hood’s Confederate troops in an ill-fated charge at Franklin, resulted in the loss of six generals and many other top commanders.

Patrick Cleburne, John Carter, John Adams, Hiram Granbury, States Rights Gist, and Otho Strahl were all killed leading their men in the assault on the Union breastworks at the Battle of Franklin. Adams was found upright in his saddle, riddled with bullets, with his horse’s legs on either side of the works. Cleburne vanished in a cloud of gun smoke and was found with a bullet in his heart. In comparison, five Confederate generals were killed at Gettysburg, three were killed at Antietam, three at Chickamauga, and two at Spotsylvania. John Brown, Francis Cockrell, Zachariah Deas, Arthur Manigault, Thomas Scott, and Jacob Sharp were also wounded and George Gordon was captured at Franklin. Perhaps spurred to greater danger by John Bell Hood’s accusation of cowardice in the ranks on the morning of the battle, no other engagement of the war saw as much devastation in the Confederate general officer corps as did the Battle of Franklin.

Confederate generals in the battle of Franklin - www.theclio.com Video: History Gone Wilder | Have History Will Travel -

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865. For illustrative purposes, the reported organization and strength of the Army of the Tennessee as of April 30, 1863, when it numbered approximately 150,000 in total, can be seen in the Official Records. The Army of Tennessee participated in most of the significant battles in the Western Theater, including the Battle of Franklin.

After the battle with John Bell Hood, John McAllister Schofield resumed his withdrawal towards Nashville, now decisively ahead of the Confederate army. John Bell Hood continued to pursue, although his army had been devastated at the Battle of Franklin and stood no chance of defeating a united Federal force. At the Battle of Nashville, fought from December 15-16, 1864, the reinforced Union army left its fortifications and brought Hood to battle, routing the Army of Tennessee once and for all. It would never fight again as a cohesive force. Hood’s unwillingness to withdraw during the Battle of Nashville compelled Schofield to comment that “I doubt if any soldiers in the world ever needed more cumulative evidence to convince them that they were beaten.”

Photo: wargame.ch Video: Reading Through History -

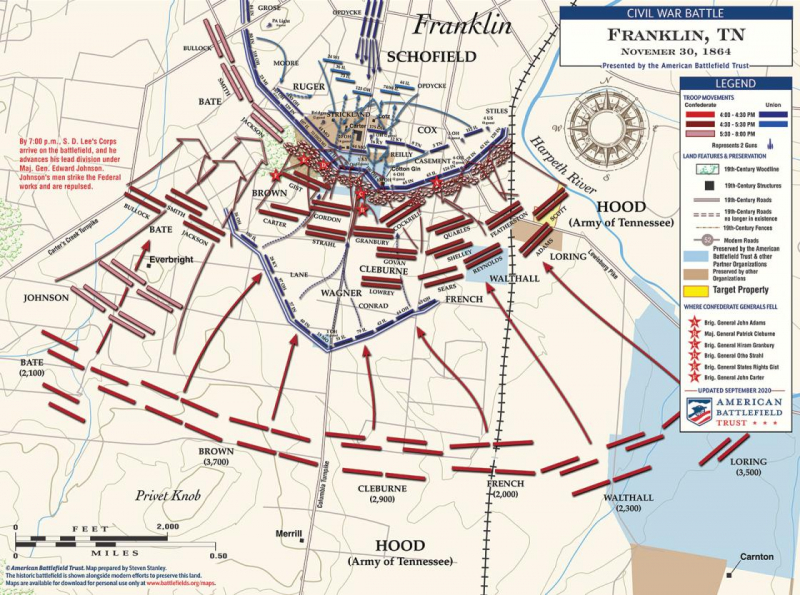

The Army of Tennessee arrived on the Franklin battlefield to participate in the Battle of Franklin from the south, in the shadow of Winstead Hill. Schofield had drawn his army up into a three-tiered series of hastily-constructed but formidable breastworks on the outskirts of town, roughly two miles north of the unfolding grey battle line. Over the protests of his lieutenants, Hood ordered a frontal assault on the Federal works. Several elements of the ensuing battle are worthy of comparison with Lee’s assault on July 3, 1863.

At Gettysburg, 12,000 Confederates attacked over a mile of open ground following a 150-gun bombardment of a Union line protected by a low stone wall. They reached their objective and held out for around thirty minutes before being repulsed, leaving about 1,415 dead or mortally wounded on both sides.

At Franklin, 20,000 Confederates, supported by just one battery, advanced over two miles of open ground and struck a Union line made up of three tiers of sturdy breastworks and abatis that in most places stood about eight feet high. The Army of Tennessee pierced the center of this line and held their position for over three hours, resulting in over 2,000 combined fatalities. Such bravery and ferocity so late in the war shocked and saddened many observers--Private Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee called it "the blackest page in the history of the war."

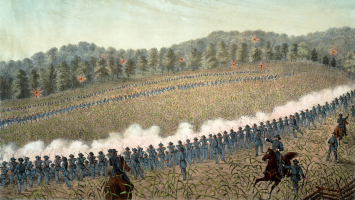

The Army of Tennessee on the battlefield - historycollection.com

Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg - theplayersaid.com -

After sunset on September 14, 1862, the confederate cannons across the road on School House Ridge vanished in the darkness. The features of the landscape begin to blur as the shell-shocked union soldiers on Bolivar Heights wondered if they could survive another day of artillery bombardment. The union troops could not rest until tomorrow, however, because general "Stonewall" Jackson's confederate army might charge over School House Ridge at any moment. To guard against such an attack, the union command established a human alarm system on this field in the form of a skirmish line. That was the first line of the Union defense at Franklin. If the confederates advanced, the gunfire from the Union soldiers on the skirmish line would reveal the location of the attack. "Stonewall" Jackson was counting on it.

The Union defenders stampeded back towards the main line after firing a single volley, the charging Southerners hot on their heels. Afraid of hitting their comrades, the riflemen on the main line held their fire as they watched the intermingled crowd of butternut and blue surge toward them. As a result, the last half-mile of the Confederate advance was largely uncontested, allowing the charge to hit the main line with full force. This was one of the few times the Confederate advanced in the Battle of Franklin.

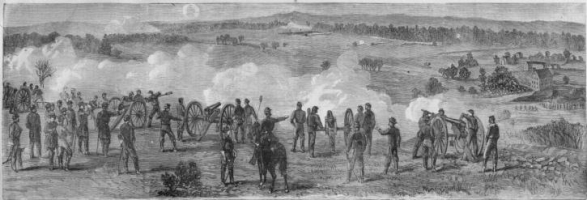

Photo: www.battlefields.org

Photo: www.battlefields.org -

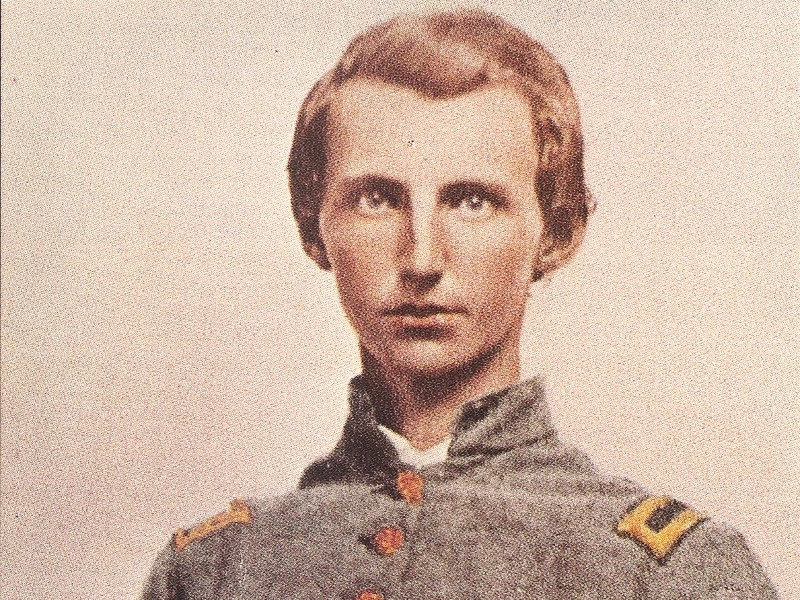

Tod Carter is the middle child in the Carter family, who had enlisted in the Confederate army in 1861. By 1864, he was the assistant quartermaster to Brigadier General Thomas Benton Smith in the Army of Tennessee, participating in the Battle of Franklin. When the Army of Tennessee crossed the Georgia-Tennessee border, the soldiers were heartened by a sign on the side of the road that read “Tennessee, A Grave or A Free Home.” Those words must have had special meanings for Tod Carter, as he will get to see his family the next day.

However, he had to participate in a fight with Smith’s brigade as part of Bates’s division. Although Tod Carter’s quartermaster duties did not require him to fight, he would not hear of it. About five hundred feet from his front yard, Tod Carter was struck by a Union bullet and tumbled into the blood-soaked grass. After the day’s carnage had ended, the Carter family emerged from their cellar only to be greeted by General Smith with the news of Tod’s wounding. By lantern light, Smith and the Carters spent hours searching the corpse-strewn battlefield for the young captain. Dying and insensible, Tod was carried back to the Carter House near dawn and set down in his sister Annie’s room. He died the next day, just one of the nearly ten thousand family tragedies that the battle wrought.

Tod Carter - williamsonsource.com Video: Tennessee Home and Farm -

Arthur MacArthur, Jr., “The Boy Colonel”, had enlisted in the 24th Wisconsin Infantry regiment underage at the beginning of the war but had already made an impressive name for himself. At the Battle of Franklin, while leading the 24th Wisconsin of Opdycke’s brigade in the middle of the reserve line, MacArthur and his men, with a shout of “Up, Wisconsin!” plunged into the melee at the Carter House after the initial Confederate charge splintered the Union defenses. MacArthur was shot off of his horse almost immediately. Bleeding from the shoulder, he drew his saber and began cutting his way through the melee towards a ragged Southern flag waving above the fray, under which MacArthur came face-to-face with a Confederate officer. The Southerner leveled his pistol and shot MacArthur in the chest. MacArthur kept his feet and ran his opponent through, but the falling officer fired once more and hit MacArthur in the leg. Gravely wounded, MacArthur was nearly trampled before his men dragged him to safety.

Miraculously, the young colonel survived his wounds and the war. His son Douglas became one of the United States’ top generals in World War II and Korea. To this day, Arthur and Douglas are the only father and son pair besides Theodore Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. to have won the Medal of Honor.

Arthur MacArthur - MassLive.com Video: City of Little Rock -

Despite the importance of the Battle of Franklin, for many years the land’s legacy was all but ignored as the city grew in the years following the war. However, the efforts of the Civil War Trust, with the help of local partners that include Franklin’s Charge, Save the Franklin Battlefield, Inc., the Battle of Franklin Trust, and the City of Franklin, have produced stirring results. Today, well over a hundred acres of battlefield land have been reclaimed and preserved, often one acre at a time over a span of many years.

Despite the efforts of so many over the years to bury history, there is so much for the visitor to see. The Carter House is considered to be “the single largest Civil War relic”. The house is where Tod Carter was born, and also the same place he died after dedicating his life to the country. His story is to be among the best stories of the American Civil War. You can go there and touch those bullet-scared walls and then out to Winstead Hill where Hood stood and watched in horror as his army seemed to vanish into the blood and night that was Franklin.

Or you can go to Ft. Granger and make your way through the center of earthen works of the Union fortifications and then make your way out to Carnton and walk through those rooms where Carrie McGavock proved herself to be the “consummate Southern Mother” as she made her way from boy to boy, with “two feet of blood on her skirts.”

Video: The Franklin Battlefield Trust

The Carter House - https://boft.org/carter-house