Top 9 Facts About The Battle of Glendale

The Battle of Resaca, from May 13 to 15, 1864, formed part of the Atlanta Campaign during the American Civil War when a Union force under William Tecumseh ... read more...Sherman engaged the Confederate Army of Tennessee led by Joseph E. Johnston. Unusual bravery was displayed during the Battle of Glendale. Please consider the following essential information to increase your understanding of this crucial conflict on the Virginia Peninsula.

-

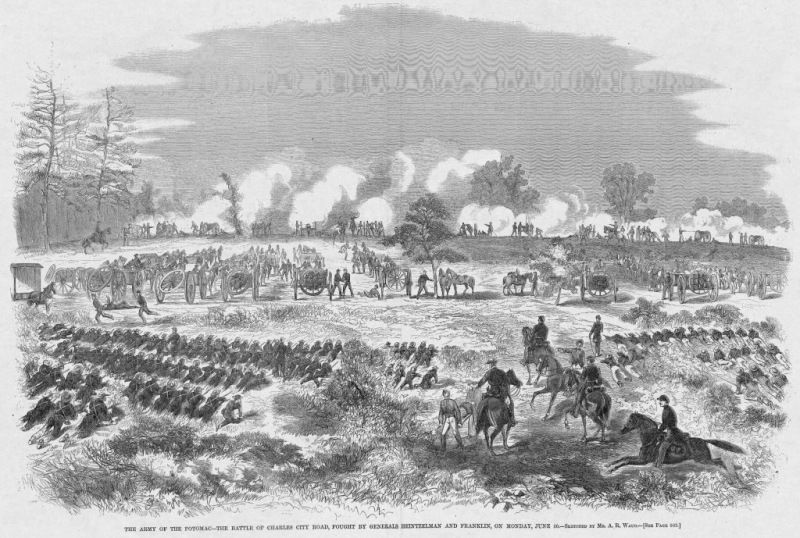

The Seven Days Battles began on June 25, 1862, with a Union assault in the minor Battle of Oak Grove, but McClellan quickly lost the initiative as Lee launched a series of assaults at Beaver Dam Creek (Mechanicsville), Gaines' Mill, Garnett's and Golding's Farm, and Savage's Station on June 29. In order to reach Harrison's Landing on the James River, where it would be secure, McClellan's Army of the Potomac kept moving backward.

The Union Army of the Potomac was less than a day's march from the Confederate capital of Richmond on June 26, 1862, following an implacable advance across the Virginia Peninsula.

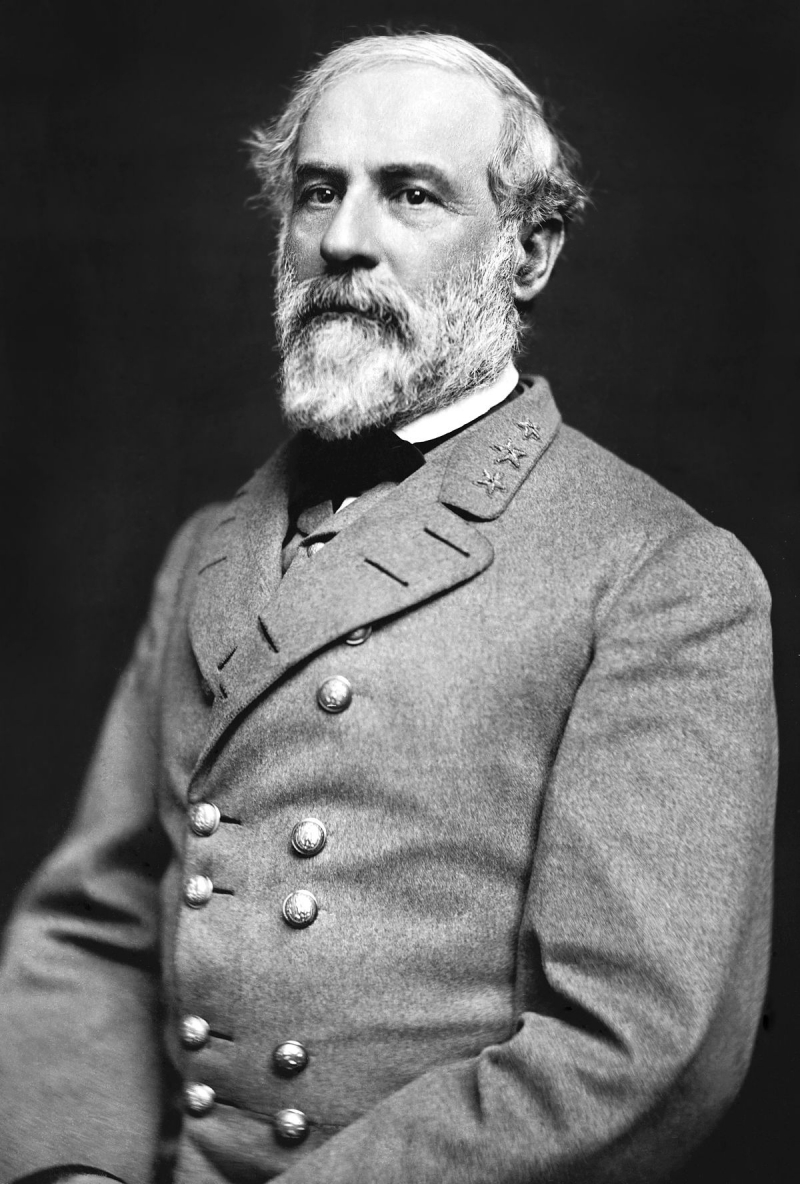

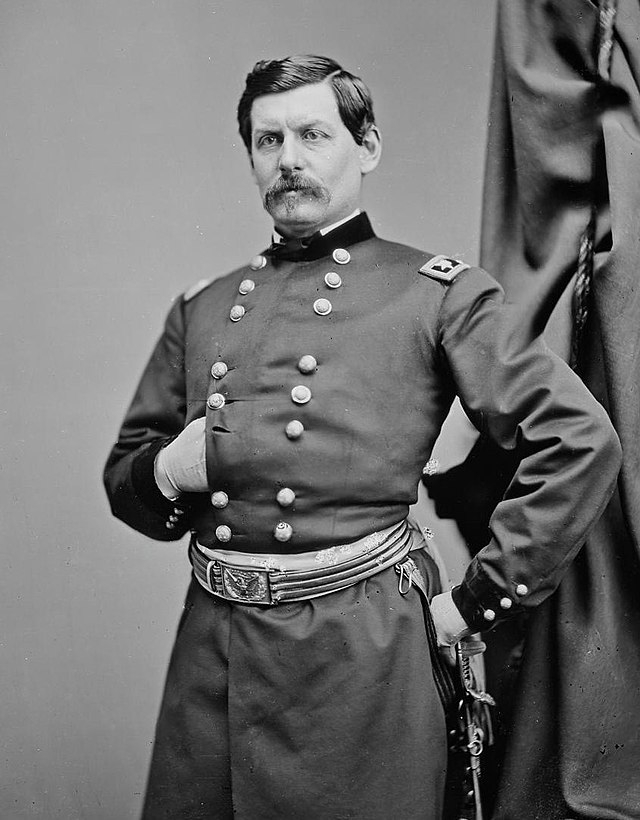

Then, for the next four days, the Confederates engaged in a series of lethal close-quarters fights in the swampy woodlands near Richmond. After the Gaines' Mill engagement on June 27, General George McClellan, the leader of the Union forces, lost contact with Washington and was forced to order a full-scale retreat towards Harrison's Landing on the James River. Robert E. Lee, who had just assumed command of the Confederate army, launched his subsequent significant attack at Glendale on June 30.

Wikipedia

History.com -

On June 30, two-thirds of the Union force, or roughly 62,000 soldiers, would have to walk through the crossroads hamlet of Glendale in order to get to Harrison's Landing. With 71,000 Confederates, Robert E. Lee was prepared to attack at that fork in the road. He envisioned a battle in which a portion of his army would hold Union soldiers off to the north and south of the crossroads while his major assault through the frail middle.

The Union troops in the Glendale area were disjointed and disheartened. On June 30, they fought with more bravery than unity. Lee's intricate battle strategy failed, as it did so frequently throughout the Seven Days, resulting in a bloody struggle that seriously wounded the Federals but did not stop them from retreating. The Union force would have been cut in half, exposed to a complex enemy nation, and at risk of annihilation had Lee taken control of the crossroads. His failure made the Union's escape all but certain.

American Battlefield Trust

American Battlefield Trust -

George B. McClellan, also known as "Little Mac," had traveled to the Virginia Peninsula in search of an American Waterloo—a significant battle that would conclude the war and make him the victor. However, the significant casualties of the current battles and the failure of the campaign, which had seemed so promising only a few days ago, left him feeling hopelessly dejected. The Union force was dispersed on the congested roads leading to Harrison's Landing on June 30, with each corps commander organizing his own evacuation and battle strategy.

To board the gunboat U.S.S. Galena on the James River, McClellan had ridden ahead of the army. McClellan dined and drank wine as the Galena steamed upriver. The lack of a strong leader in charge severely hurt the Union army at Glendale. The soldiers at Glendale were thrown together from several commands without the required command presence to properly react to enemy moves because McClellan failed to organize or oversee the army's retreat. The Union soldiers formed a crooked, disconnected line when they deployed, with the flanks of one unit not seamlessly joining the flank of another, creating a field of "bite-sized" pieces of the army. These isolated units would be in need of either a hasty withdrawal or immediate support when Lee's men emerged from the woods.

Wikipedia

Wikiwand -

The cautious General Benjamin Huger, whose name is pronounced "You-Jee," was supposed to launch the first attack on the Union center but was thwarted by a barricade of downed trees in his path. Huger decided against sending out personnel to clear the obstruction and instead cut a new path through the trees. After losing an artillery battle while advancing against the extreme Union left at Malvern Hill, General Theophilus Holmes decided against moving his infantry forward. Lee's plan did not heavily rely on them, but General John B. Though they were not a major factor in Lee's plan, General John B. Magruder's troops were blocked by Holmes's immobile force and, thus, more than one-third of the Confederate army failed to reach the Glendale battlefield.

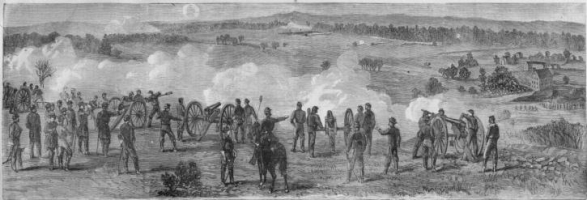

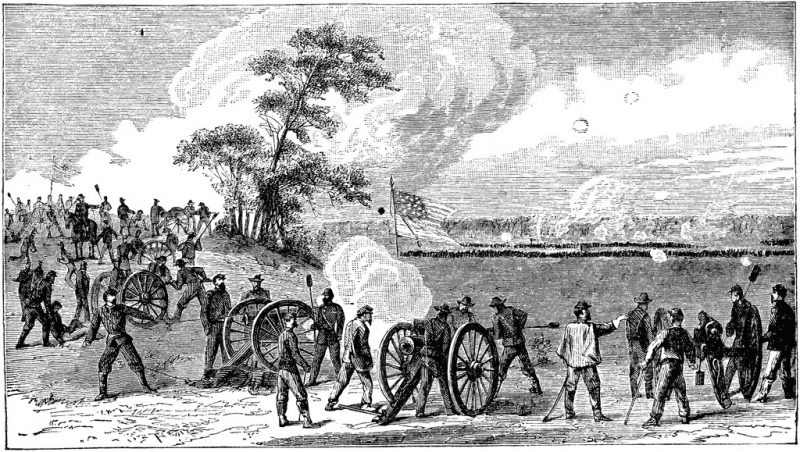

The majority of the Union army was uncommitted as a result of Lee's generals' mistakes, allowing them to move reinforcements to vulnerable areas. Just before 5:00 p.m., Lee dispatched General James Longstreet's division straight for the Glendale intersection, much to his dismay. 25,000 of Lee's planned over 70,000 soldiers were defeated at Glendale due to mistakes made by the Confederate leadership.

Encyclopedia Virginia

American Battlefield Trust -

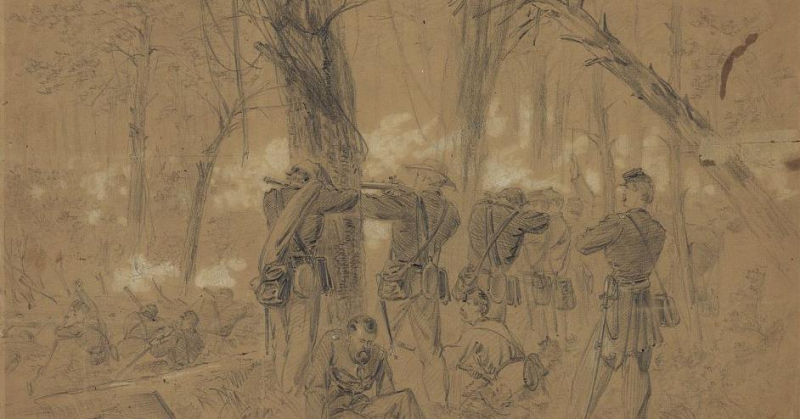

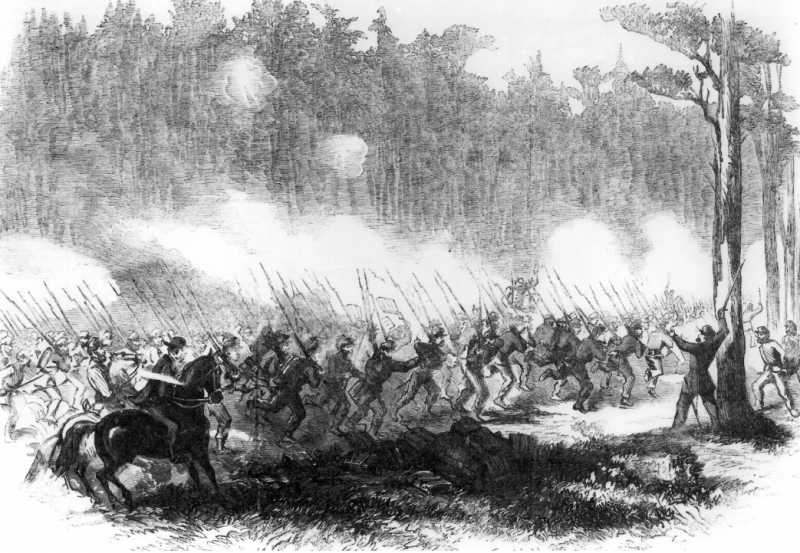

At the Battle of Mechanicsville on June 26, the Pennsylvania Reserves, a Union infantry division commanded by General George McCall, had experienced their first encounter with close-quarters combat and were compelled to withdraw. They suffered a grueling day of Confederate attacks on June 27 at Gaines' Mill, and one of their best general officers, John Reynolds, was captured. The weary Pennsylvanians were now at Glendale, in the middle of the Union battle line, gazing into the thick forest to the west, where the Confederate army was hidden.

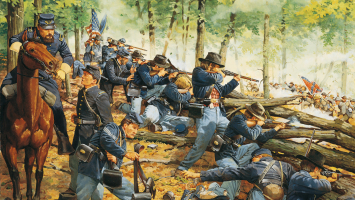

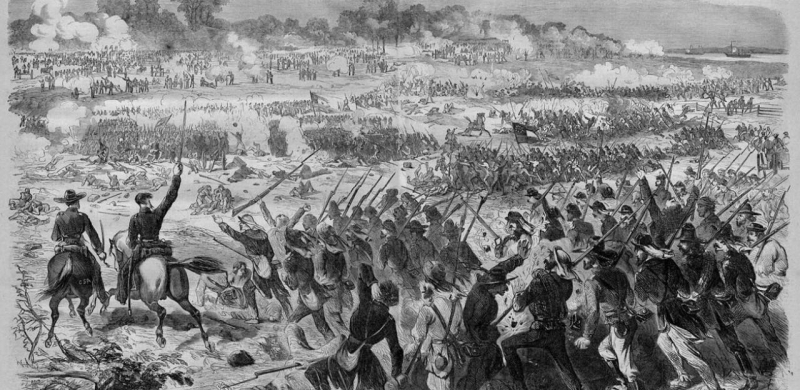

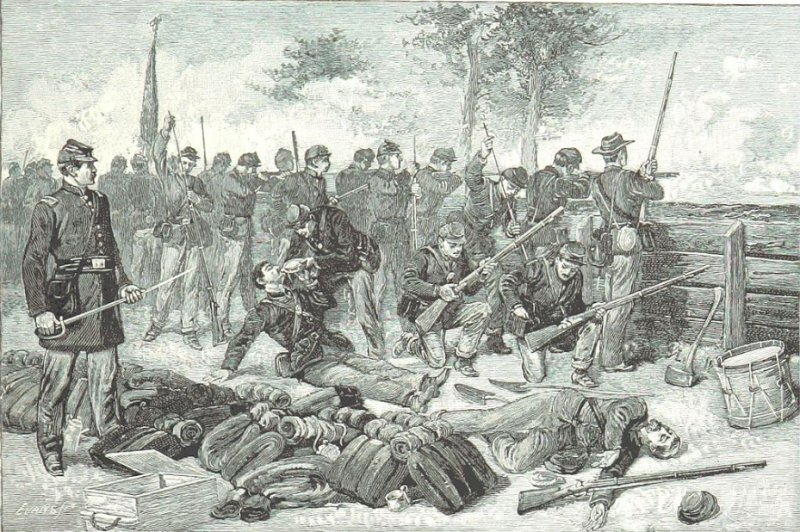

With a rebel scream, Longstreet's division emerged from the forest around 5:00 p.m. By driving in the left-most section of the Pennsylvanian skirmishers, capturing Captain Otto Diederichs' artillery, seizing the Whitlock farmhouse, and turning the Pennsylvanians' left flank, General James Kemper's Virginia brigade turned the battle. General Micah Jenkins' second Confederate brigade made a break for the six cannons of Captain James Cooper's battery in the middle of the Union line. One witness said there was "more actual bayonet, & butt of the gun, melee fighting than any other occasion I know of in the war" during the Pennsylvanians' hasty attempt to defend their firearms. The field was torn apart by fierce hand-to-hand combat before both sides withdrew, bloodied and worn out, into their respective wooded positions.

American Battlefield Trust Tabletop History -

At the age of sixteen, New York City native Benjamin Levy enlisted in the Union army. Levy was posted as a drummer boy to the 1st New York Infantry's musician corps, despite the fact that he was still technically ineligible and the regulation was frequently broken.

He was in a tent on June 30, 1862, just to the north and east of the Glendale intersection. Levy made the decision to take action as the first line's cannonade of gunfire began to intensify. The young soldier hurried to join the regimental combat line as it marched into the dusk battle at the Glendale crossroads, leaving behind his drum and taking a sick comrade's musket. The regiment's color guard was swiftly devastated by Confederate fire, which made the New Yorkers hesitate. Levy proceeded to the front of the formation as the crisis developed and once more raised the battle flags. The line steadied around the former drummer boy and, with the help of reinforcements, the Confederates were eventually repulsed. Levy is the first person of the documented Jewish faith to win the Congressional Medal of Honor.

The Jewish American Military Historical

U.S. Army -

The Union battle north of the Glendale crossroads was led by Phil Kearny, a one-armed Army regular and one of the Army of the Potomac's best generals. The area's topography was complicated and heavily forested. Kearny overstepped his bounds when conducting reconnaissance in the Confederate tree line during a pause in the action. A young officer who approached him and said, "What shall I do next sir?" made this clear. Kearny observed that there were numerous enemy skirmishers there in the woods. Why do what you have always been instructed to do, do dammit you! Kearny replied sharply. The officer, mortified to have received such condemnation from a superior, did not question Kearny further as the quick-thinking New Jerseyan slipped back to his own lines.

After the Seven Days Battles concluded, speculation that Kearny might succeed McClellan spread across Washington. However, on September 1, 1862, Kearny was shot dead at the Battle of Chantilly after a similar scouting encounter went wrong, putting an end to the whisperers.

American Battlefield Trust

The Wild Geese -

Both sides were rattled and worn out after the brutal initial combat over the Glendale crossroads. Union and Confederate reinforcements hastened into the conflict as the situation was still quite uncertain. First to arrive were more Confederates, who formed a formidable second line of about 10,000 soldiers from the Longstreet and A.P. Hill divisions. The Southerners were on the verge of a breakthrough as they swept into the battered Union elements left over from the initial phase of the battle when new Union troops started to arrive.

More than 12,000 of these men were transferred from the areas that Benjamin Huger and Stonewall Jackson left uninfected. At a crucial juncture in the war, they arrived at the fork in the road and replenished the Union line. The exhausted assailants collapsed on the ground and traded volleys in the dimming light, which caused the Confederate effort to stop. The combat continued until the darkness engulfed them. Despite their early successes, the Confederates were unable to blockade the crucial intersection.

Emerging Civil War

The Wild Geese -

Forces from the Union continued to withdraw from Harrison's Landing after securing the roads. The majority of McClellan's men were stationed at Malvern Hill on July 1, a crucial site that offered protection from the west and the north for the invasion. In their final attempt to completely destroy their northern rivals, the Confederate infantry attacked the heights and fiercely scattered toward the Union line. The bloody frontal assault at the Battle of Malvern Hill the next day is the result of the missed opportunities at Glendale.

The futile attacks into a horde of guns could have been avoided if the Battle of Glendale had gone differently, perhaps more as planned. "On two occasions in the four years, we were within reach of military successes so great that we might have hoped to end the war with our independence," wrote Confederate artillery chief Edward Porter Alexander in a postwar letter. ... The first occurred in July 1861 at Bull Run. I consider this [second] opportunity of June 30, 1862, to be the greatest of all.

Florida Center for Instructional Technology

The Civil War Monitor