Top 10 Facts about the Native Americans in the American Revolution

The Indigenous peoples of the continental United States are referred to as Native Americans, American Indians, First Americans, Indigenous Americans, and other ... read more...titles. Most Native Americans who joined the fight during the American Revolution supported the British because of their trading ties and the belief that a defeat for the Americans would put an end to further settlement on Native American territory. And here are some facts about the Native Americans in the American Revolution.

-

The Six Nations were generally successful in upholding their neutrality for the majority of the French and Indian War. The Confederacy cemented its alliance with the British as the war's conclusion drew closer. The Six Nations, however, would be under pressure from the American Revolution that they could not withstand. The bulk of the Oneida people and some of their Tuscarora descendants chose to support the American cause, although the majority of the Confederacy ultimately continued to support England. Sir William Johnson's efforts had a significant role in the Six Nations and England's alliance. On the other hand, Rev. Samuel Kirkland played a role in the alliance between the Americans and the Oneidas.

Geographically speaking, the Oneida lived on territory in central New York and were closest to the eastern seaboard. They developed into the Iroquois Confederacy's most steadfast supporters of the Patriot cause. The Oneida's decision to side with certain allies was also influenced by their loss of sovereignty under the British. Sir William Johnson had overstepped his authority during discussions for the Boundary Line Treaty of 1768 (held at Ft. Stanwix), eventually wearing the Oneida down and getting their consent to expand the boundary line further into Oneida territory. Johnson also hindered the Oneida's progress toward self-sufficiency, turning down their request for a blacksmith to be stationed in their villages to do repairs right away. The Tuscarora, who were helped by the Oneida to gain entry into the six nations, had groups that backed opposing sides in the struggle and shared reservation ground with the Oneidas after the fighting before receiving their own designated place

Photo: Texas Homeless Network

Photo: American Battlefield Trust -

Native Americans from the Catawba tribe supported patriot partisans and militia in operations in North and South Carolina would be the second fact about the Native Americans in the American Revolution. The Piedmont, a rich region that runs across the Carolinas and is home to the Catawba, is where they lived. They comprised a varied mix of about 15 different ethnic groups. In the wake of disease, conflict, enslavement, and dependence on trade as they united in the early 18th century, the various groups who made up the Catawba nation reinvented their identities. However, the smallpox outbreaks that occurred after the Seven Years War furthered their decline. The Catawba were in a tough situation by the time of the American Revolution. They turned to renting their reservation grounds as a way of financial survival because they were surrounded by unfriendly South Carolinians.

Even though the Catawbas supported the British during the French and Indian War, a reserve in South Carolina was established for them just before the American Revolution. Many of the Catawba people's homesteads were set on fire as a result of the British presence in the region between 1780 and 1781. They moved further into the American camp as a result, serving at locations like Guilford Courthouse in March 1781 and with the renowned militia leader General Thomas Sumter in South Carolina. After the British took Charleston, South Carolina, in 1780, they furthermore gave colonists food and assistance.

Photo: Legends of America

Photo: Colonial Quills -

The Mohican, Housatonic, and Wappinger peoples made up the multiethnic Native population from whom the Stockbridge-Mohicans originated. The Mohicans, who currently reside in Wisconsin, are a federally recognized people group. The Mohicans inhabited western Massachusetts and the Hudson Valley prior to the Revolutionary War. The Mohicans who lived there were given the new moniker Stockbridge Indians or Stockbridges when missionaries founded the Massachusetts town of Stockbridge in the 1730s. The English colonists sought to convert the Stockbridges to Christianity, and the tribe also acquired parts of their cultural customs and beliefs, fusing them with local customs.

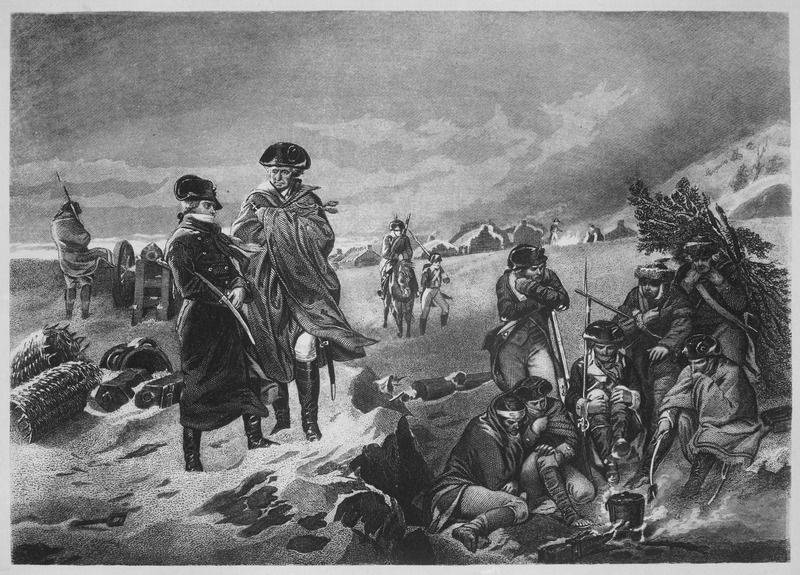

The Stockbridges allied with the Revolutionaries when the Revolutionary War started. The Stockbridge marched south after the battle of Saratoga and joined Washington's troops at Valley Forge. They engaged in combat at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778. The Stockbridge neighborhood met with Revolutionary leaders at the start of the war to forge an alliance. They arrived on the battlefield shortly after that. Stockbridge Indians volunteered to be minutemen when the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord in 1775. Later, at the Battle of Bunker Hill, some Stockbridges fought alongside New Englanders. Due to their participation in these early conflicts, the Continental Congress gave General George Washington permission to actively recruit Stockbridge Indians in 1776. They acted as scouts for the Continental Army throughout the whole conflict, providing crucial local knowledge that helped the army prepare for swift ambushes. The Stockbridge-Mohican served as their ambassadors and contributed to intelligence collection as well as diplomatic relations with the United States and other Native American tribes.

Photo: American Battlefield Trust

Photo: WorthPoint -

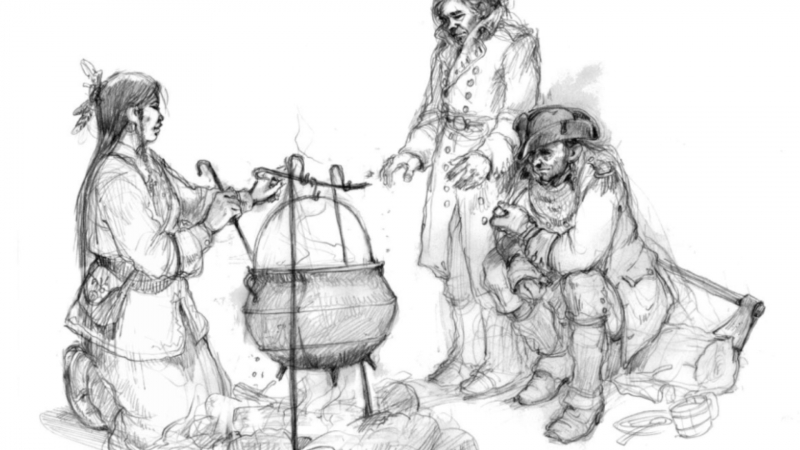

Another fact about the Native Americans in the American Revolution is that Oneida Polly Cooper journeyed to Valley Forge with male warriors during the Continental army's winter encampment. Oneida woman from the New York colony named Polly Cooper participated in a 1777 mission to support the Continental troops during the American Revolution. During the winter of 1777–1778, troops were encamped at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Cooper and other Oneida locals traveled hundreds of miles on foot to deliver the Continental Army's starving troops hundreds of bushels of white maize. She stayed with the Continental Army for a while to instruct the men on the proper way to boil white maize for digestion, which required a distinct cooking method. She also assisted with medical assistance and natural medications.

Understanding Polly Cooper's story requires knowing that George Washington and his soldiers were acquainted with the Oneida Indian Nation. The leadership of the congregational preacher Samuel Kirkland and their contempt for the British-appointed native superintendents Sir William Johnson and his son-in-law Guy Johnson led the Oneida Indian Nation to embrace the American cause. In order to help Washington at Valley Forge, a group of 47 Indian men, Polly Cooper, and Louis de Tousard departed on April 25. They were carrying bushels of grain. After the war, the Continental Army attempted to compensate Polly Cooper for her heroic service, but she rejected the offer, insisting that it was her responsibility to aid her comrades in need. A black shawl that Cooper had spotted in a store window was given to her as a gift. She received the shawl in exchange for her services as an army cook, for which Congress authorized funds. The Cooper family still looks after the shawl, which is almost in flawless condition.

Photo: Wikipedia

Photo: Revolutionary War Journal -

The Oneida were able to contribute the most physically to the war from late 1777 to early 1778. At the Battle of Oriskany, Herkimer's militiamen engaged American Loyalists and British allies from the Six Nations League. Han Yerry Tewahangarahken, an Oneida War Chief, his wife Two Kettles Together (Tyonajanegen), and their son Cornelius stood out in particular. Han Yerry murdered nine of the adversaries by the end of the conflict. 150 soldiers were supplied by the Oneida to Gen. Horatio Gates' army during the final stages of the Burgoyne Campaign. This gang was successful in intimidating British forage expeditions and sentry stations. The Oneida sent 50 men to serve with Washington's army at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777–1778.

The Oneidas served as skirmishers and scouts alongside Daniel Morgan's Virginia riflemen, giving early notice of the approaching British forces. This made it possible for the Marquis de Lafayette's army to conduct a well-organized combat retreat. There is a plaque in Lafayette Hill, Pennsylvania's St. Peter's Lutheran Church commemorating the six Oneidas who lost their lives in the battle. When they heard the approaching British soldiers, as many as 9,000 of them, the Oneida and the riflemen were scouting the area. The small group of Oneida and riflemen continued to fire at the British from the trees, unafraid. The British mounted a horse charge after realizing they were facing a force of about 100 men when they first recognized how small the attack force was.

Photo: Oneida Indian Nation

Photo: Tara Ross -

Joseph Brant, also known as Thayendanegea, was a Mohawk military and political figure who lived in modern-day New York and was intimately affiliated with Great Britain during and after the American Revolution. He died on November 24, 1807, at the age of 74. He may have been the Native American of his generation most well-known to both Americans and the British. He interacted with many of the most important Anglo-American figures of the time, including King George III and George Washington. Brant commanded "Brant's Volunteers," a group of Mohawk and colonial Loyalists that fought in a bloody partisan conflict on the frontier of New York during the American Revolution. He was given the nickname "Monster Brant" by the Americans who accused him of carrying out atrocities, however historians later claimed that the claims were untrue.

Guy Johnson (c. 1740 – 5 March 1788) was an Irish military officer and diplomat. He moved to the Province of New York as a young man and worked with his uncle, Sir William Johnson, who was the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies during the Revolutionary War. He fought on the side of the British. Guy Johnson succeeded his uncle as British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, serving as Sir William's deputy. He discovered a lot about the Mohawk and Iroquois people. Guy took over as supervisor after William passed away in 1774, just before the war.

In 1774, Guy Johnson succeeded his uncle as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and it was largely due to his efforts that the Iroquois Confederacy's majority of tribes joined the British cause. As a prominent Mohawk military and political figure, Joseph Brant fought a partisan battle in New York on behalf of the British. That's all about the sixth fact about the Native Americans in the American Revolution we want to mention.

Joseph Brant (Photo: American Battlefield Trust)

Guy Johnson (Photo: Wikipedia) -

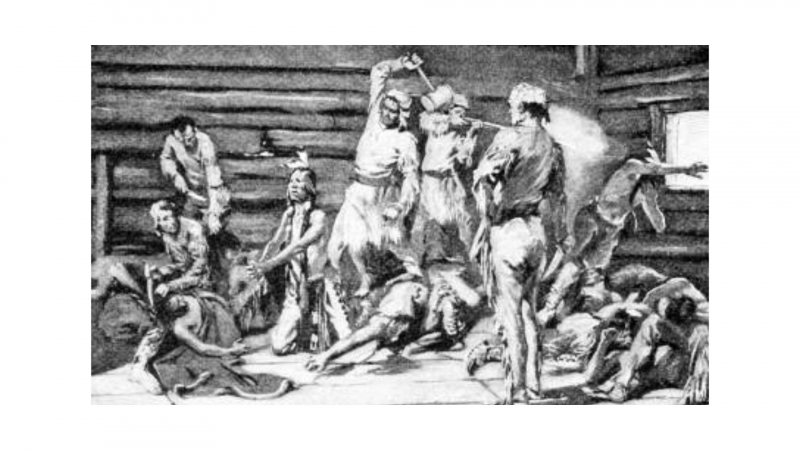

The American Revolutionary War's Gnadenhutten Massacre, also known as the Moravian Massacre, took place on March 8, 1782, in the Moravian missionary settlement of Gnadenhutten, Ohio Country. It resulted in the deaths of 96 pacifist Moravian Christian Indians (mainly Lenape and Mohican). The Moravians were looked down upon by both the British and the Americans due to their adherence to Christian pacifism, which prevented them from taking sides during the American Revolution. The Pennsylvania militia came upon the Moravians as they were gathering crops and made false promises to the Moravians that they would be "relocated away from the fighting parties." However, after they had gathered, the American militia rounded up the unarmed Moravians and claimed they intended to put them to death for being spies, accusations the Moravians refuted.

The Moravians spent the night before their execution praying and reciting Christian songs and psalms after requesting permission to pray and worship from their captors. Despite being outnumbered by those who wished to murder the pacifist Moravians, 18 U.S. militiamen resisted the killings; those who opposed the killings abstained from the massacre and kept their distance from the murderers. The American soldiers "dragged the women and girls out into the snow and systematically raped them" before killing them. The Moravians sang hymns and spoke words of encouragement and consolation one to another until they were all slain" as they were being executed.

Photo: Ohio History Central

Photo: history.com -

The next fact about the Native Americans in the American Revolution related to civil war among Native American. The British, who had put some restrictions on colonial development on Native American territory, looked to pose a far larger threat to the majority of Native peoples than an independent United States committed to westward expansion. When it came to keeping tribal allies, the British had many advantages over the Americans. British officials could provide the trade commodities (such cloth, metal tools, rifles, and ammunition) that Native people had grown to rely on because they had considerably more financial resources and control over the sea. Many countries had come to view the British Crown as a reliable defender and ally. The fact that these countries were aware that an American triumph would open their territory to invasion by settlers and soldiers was crucial.

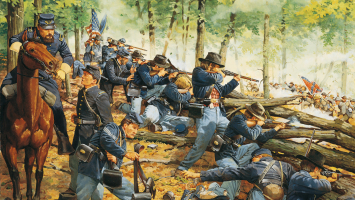

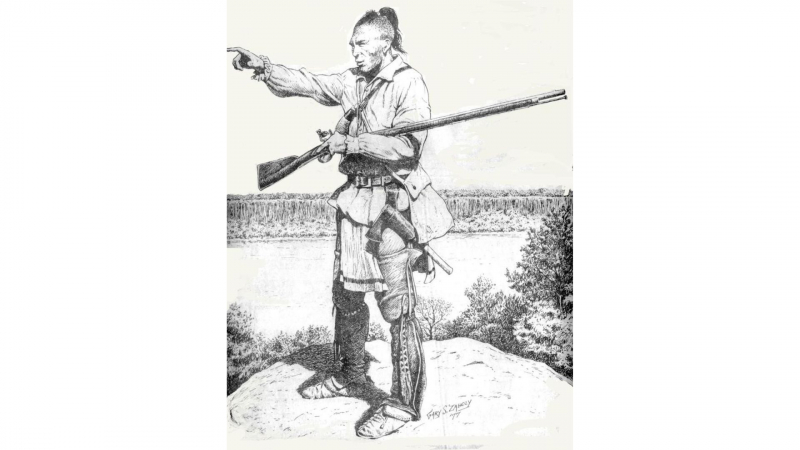

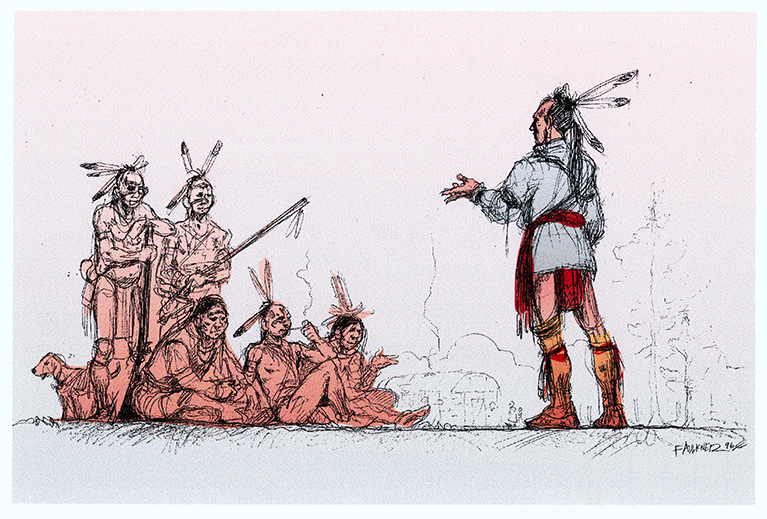

Some Native American tribes, on the other hand, choose to back the Revolutionaries, whom they regarded as neighbors and allies. These American Indian tribes had the view that if the Revolutionaries were successful, they would grant them the right to continue ruling over their ancestral territories. Three American Indian tribes which are Oneida, Mohawk, and Stockbridge-Mohican—that took part in the Revolutionary War are depicted in paintings by Don Troiani. The Iroquois Confederacy included the Oneida and Mohawk. Four of the Confederacy's six member countries, including the Mohawk, actively sided with the British, whereas the Oneida and Tuscarora backed the Revolutionaries. The Stockbridge-Mohican and other Native Americans also joined the Revolution.

Photo: American Battlefield Trust

Photo: American Battlefield Trust -

The Cherokees were one of the greatest Native American tribes in the South. The Cherokee fought as allies of Great Britain against American patriots during the Revolutionary War, in addition to fighting against settlers in the Overmountain region and later in the Cumberland Basin to defend against territorial colonization. The North was the center of British strategy, not the remote outposts, particularly those in the west. With the exception of supplies from British coastal ports and a few collaborative operations in South Carolina, the Cherokee were therefore on their own.

John Stuart, the British superintendent of the South, had intended to utilize English troops and Indian tribes against the colonists when the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775. Their choice to support the British was influenced by white encroachment at the Tennessee-North Carolina boundary along the Watauga, Nolichucky, and Holston Rivers, as well as a delegation of Shawnee and other northern Indians pushing the Cherokee to fight against the Americans. White North Carolinians gained independence during the American Revolution, but the region's native populations, particularly the Cherokee, were captured. Nevertheless, despite suffering military loss, the Cherokee were able to preserve some degree of political independence and cultural purity. The United States started a "civilization" program in an effort to integrate the Cherokee people into mainstream American society with the Treaty of Holston (1791). This primarily means switching to sedentary agriculture. As a result, Indians could now easily obtain more Cherokee territory because they could no longer use their vast hunting areas.

Photo: Age of Revolutions

Photo: Journal of the American Revolution -

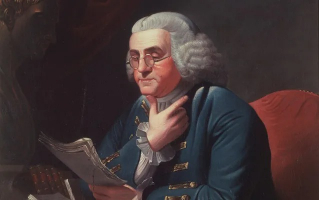

Conotocarious is the last fact in the list facts about the Native Americans in the American Revolution. George Washington was given the nickname Conotocarious, demonstrating the communication and memory of the many eastern Native American tribes. When George Washington made his initial contact with Native Americans in 1753, he was given the name, which means "town destroyer," that had been given to his ancestor in the 17th century. Washington carried the moniker with him throughout the American Revolution and into his administration.

George Washington offered his services to the Governor of Virginia as an ambassador to deliver a message to the French commander Jacques Le Gardeur in the fall of 1753 as French forces pushed into the Ohio Valley to construct a number of forts. On October 31, 1753, Washington was given his commission, and he immediately left. Washington had a small group with him. Because of the elder Washington's reputation, when the Native Americans met his great-grandson in 1753, they referred to him as Conotocarious. Later, Washington noted that this name had been "remembered by them ever since in all their transactions during the late War, having been entered in their Manner and communicated to other Nations of Indians." In a letter he sent to translator and negotiator Andrew Montour in October 1755, Washington referred to himself as "Conotocaurious" and expressed his wish for the Oneida to relocate along the Potomac.

Photo: history.com

Photo: history.com