Top 10 Facts About The Philadelphia Campaign

During the American Revolutionary War, the British launched the Philadelphia campaign (1777–1778) in an effort to seize control of Philadelphia, which at the ... read more...time was home to the Second Continental Congress. This is an important milestone in the American Revolution. Let's explore 10 facts about the Philadelphia Campaign to know more about this event!

-

Throughout the war, Philadelphia served as the nation's capitol is the first fact about The Philadelphia Campaign Toplist want to share. The 1790s saw Philadelphia, where the U.S. Constitution was created in 1787, act as the country's capital for ten years. In a variety of ways, from the political drama to the development of a national culture, it was a decade of nation-building. The United States Congress approved the Sedition, Alien, and Fugitive Slave Acts while convening in the County Court House (Congress Hall). Philadelphia attracted painters who came to create portraits of politicians and other notables because so many of the nascent nation's famous individuals were there. With the growth of leaders like Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, and James Forten, the city also became a center for the development of African American communities.

The most populous urban center in the young country, according to the results of the first U.S. Census, was Philadelphia, together with its neighboring suburbs Southwark and the Northern Liberties. Philadelphia's success, as well as failure, went beyond its borders. The Lancaster Turnpike, built between 1793 and 1795, increased the city's commercial connections to the interior of Pennsylvania. Philadelphians with the resources to do so fled to the countryside around Grays Ferry, Germantown, and South Jersey in 1793 when yellow fever struck.

Photo: American Battlefield Trust

Photo: Architect of the Capitol -

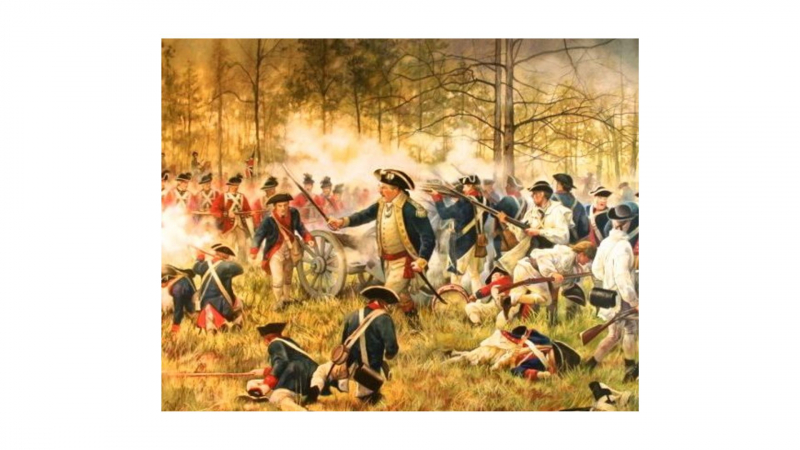

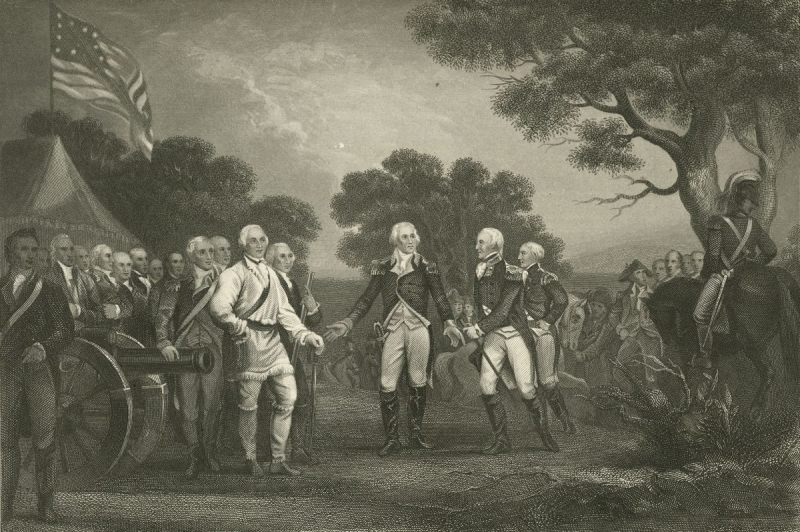

Midway in 1777, Howe began his effort to seize Philadelphia, the nation's capital. As General George Washington tried to avoid committing his restrained but untested Continental Army, the forces had already engaged in skirmishes. Howe intended to engage Washington in a decisive battle and was confident of success. The Continental Army of General George Washington, consisting of about 15,000 soldiers, and about 16,000 soldiers under General Howe, set sail from New York City in July 1777. They met near Chadds Ford, on Brandywine Creek in southeast Pennsylvania, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) southwest of Philadelphia.

After capturing the city, the British positioned 9,000 soldiers in Germantown, which is located 8 kilometers (5 miles) north of Philadelphia. To remove a row of chevaux de frise barriers from the river, the British took control of Fort Billingsport on the Delaware in New Jersey on October 2. Benjamin Franklin is credited with the idea for those obstructions, and Robert Smith created them. A third line, fortified by Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer, was located closer to Philadelphia after an undefended line had already been taken at Marcus Hook. On October 4, Washington launched a fruitless assault on Germantown before withdrawing to wait for a British counteroffensive.

Photo: history.com

Photo: Alchetron -

The following fact in the list of facts about The Philadelphia Campaign is that Even though they fought valiantly, the Americans lost the battle of brandywine, which was fought only ten miles from Philadelphia. The American Revolutionary War battle of Brandywine, fought on September 11, 1777, close to Philadelphia, saw the British triumph over the Americans while retaining control of the Revolutionary army. Sir William Howe, a British general, was persuaded to go to Philadelphia on the impression that Pennsylvania would essentially be eliminated from the war due to the sizable Tory population there. That action left General John Burgoyne's forces in northern New York on their own, which directly contributed to the British defeat at the Battles of Saratoga on September 19 and October 11, victories that persuaded France to support the American war effort and marked a significant turning point in the war.

The British won the Brandywine Battle decisively, taking control of the rebel capital in the process. The Continental Army's brave effort demonstrated that the rebels could withstand the entire force of the British Army and survive, giving them the confidence to fight another day. Nevertheless, the victory offered the British few strategic advantages. Howe's wing eventually overcame the newly formed American right wing, which was stationed on various hills, after a fierce battle. At this juncture, the American left wing was destroyed by Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen's onslaught on Chadds Ford. Bringing up portions of General Nathanael Greene's division as Washington's army began to retreat, he was able to delay Howe's column long enough for his army to flee to the northeast. General Casimir Pulaski of Poland helped Washington escape by protecting his back. Philadelphia was vulnerable as a result of the loss and the subsequent actions. The city was under British rule for nine months, from September 26 to June 1778, after the British had taken it two weeks later on September 20.

Photo: History on the Net

Photo: British Batlles -

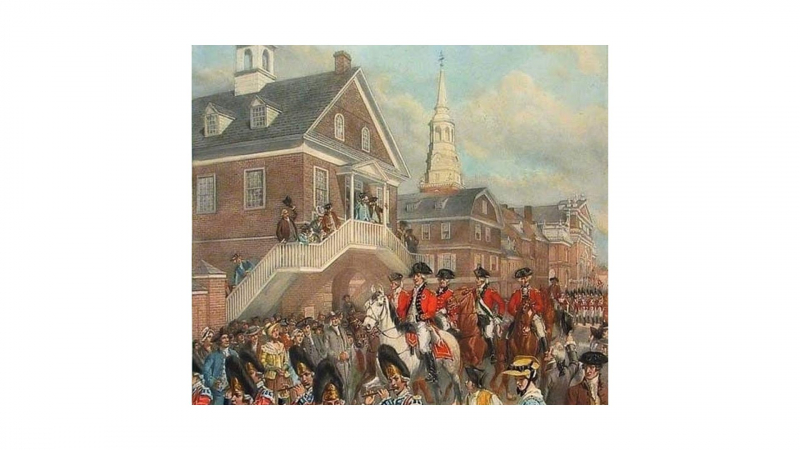

In Philadelphia, the British entered on September 26, 1777. Many businessmen and nationalists had left the city in advance of their arrival. The situation was made worse by the fact that Washington's forces had pillaged Philadelphia and taken anything that the British may have found useful. Most of the residents that stayed were a mixture of Quakers, Loyalists, and the underprivileged. Children and women made up three-quarters of the total population. The majority welcomed British authority because they had always regarded themselves as loyal English citizens. Additionally, people had grown weary of the city's rulers' excessive patriotism for a long time.

The British held the American capital for almost a year. Patriot civilians suffered the occupation while Loyalist civilians welcomed the British. Merchants from other towns began relocating, British officers began residing in the most prestigious homes, and the occupying Englishmen installed a puppet administration made up of locals who supported the throne. George Washington and the Continental Army persisted in fighting while the Continental Congress evacuated to York, Pennsylvania, despite the loss of their capital city.

After joining the war on the side of the Americans, France's entry into the conflict rendered the British position in Philadelphia unsustainable. General Clinton was compelled to lead his British-Hessian troops to New York City on foot in order to evade the French fleet. The Patriots arrived in Philadelphia the day after the British left, and the city's loyalists fled by sailing down the Delaware River. The force that peacefully took over the city under the command of U.S. General Benedict Arnold was given the position of military governor. The Continental Congress left the city on June 24 and relocated to temporary quarters in York, Pennsylvania.

Photo: American Revolution Podcast

Photo: Philadelphia Reflections -

Against October 4, 1777, Washington commanded an attack on the British at Germantown, just outside of Philadelphia. The Americans first appeared to be winning the battle, but soon the situation changed, and Washington was forced to retreat. Despite suffering several setbacks, Washington saw a chance to trap and soundly destroy the dispersed British force. As his final effort of the year before moving into winter quarters, he made up his mind to attack the Germantown garrison. His strategy planned for an intricate and audacious assault; four columns of soldiers were to attack the British garrison from various angles at night in order to form a double-envelopment. In the same way as the Hessians were at Trenton, Washington hoped that the British would be taken by surprise and overpowered.

On October 3, after nightfall, the American force started their march of 16 miles (26 km) in the direction of Germantown. The troops were told to put a piece of white paper in their hats to identify them as friendly or hostile in the shadows. The Jäger pickets failed to notice the Americans, which prevented the main British camp from being informed of the American advance. For the Americans, it appeared that their endeavor to build on their triumph at Trenton was going well. The darkness, however, made it very difficult for the American columns to communicate with one another, and as a result, progress was slower than anticipated. The majority of American forces were too far from their intended positions at dawn, losing the element of surprise they had previously enjoyed. That's all about the fifth fact about the Philadelphia Campaign.

Photo: American Battlefield Trust

Photo: British Battles -

Valley Forge was the third of eight winter encampments for the main body of the Continental Army, commanded by General George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. In September 1777, as Philadelphia was being taken over by the British, Congress fled the city. After failing to retake Philadelphia, Washington's 12,000-man army spent the winter in Valley Forge, which is located about 18 miles (29 km) northwest of Philadelphia. They stayed there for six months, from December 19, 1777, until June 19, 1778. At Valley Forge, the Continentals battled a serious supply shortage while reorganizing and retraining their regiments. The number of soldiers who died from illness, which may have been exacerbated by malnutrition, ranged between 1,700 and 2,000.

Washington met with his officers to decide which location would be best for his troops. Around 12,000 soldiers, craftspeople, women, and kids made up the Continental Army that marched into Valley Forge. Patriot leaders and legislators struggled to feed a populace the size of a colonial city over the whole winter. More than 1,000 soldiers and maybe as many as 1,500 horses perished that winter due to famine and sickness. The men experienced constant, agonizing cold and hunger. The Continental Army had trouble keeping things clean. The encampment's unsanitary environment led to the outbreak of scabies and other, more deadly diseases. Water for bathing, washing, and cooking was scarce in the army. Dead horse carcasses were frequently left unburied, and Washington disliked the scent in some spots.

Photo: history.com

Photo: history.com -

The British left Philadelphia in june 1778 after word reached Philadelphia that France had sided with America would be the next fact about the Philadelphia Campaign. In 1778, General Henry Clinton, the current British leader, departed Philadelphia. It was less crucial for them to control the American capital after they realized other British interests were in danger all around the world. The tide of war was shifting while Howe and his troops spent the winter in Philadelphia. Burgoyne submitted at Saratoga on October 17, 1777, without assistance from Howe. The French were inspired to join forces with the Americans by this American success. The French navy was a threat to British objectives in America, thus they could no longer afford to occupy Philadelphia, especially since they had achieved little there. The directive was given for General Henry Clinton to leave Philadelphia and head back to New York. In June 1778, the British army departed Philadelphia with about 3,000 allies.

Black Philadelphians, both free and enslaved, were forced to make difficult decisions as a result of the British occupation and departure of the city. It was unclear in 1777 and 1778 whether a British or American victory would be more likely to result in independence and expanded rights. On the one hand, Philadelphia's Quaker and abolitionist attitude had been escalating in the ten years prior to the conflict. The number of free Black people in the city increased as more masters released their slaves. A victory for the Americans in Philadelphia would have given slaves there hope for more manumissions or even the abolishing of slavery.

Photo: HistoryNet

Photo: Posterazzi -

On this date in history, June 18, 1778, the British army leaves Philadelphia, and the Americans recover the city. British General William Howe took control of Philadelphia in September 1777 in an effort to put an end to the American uprising by killing off its head there. However, the Continental Congress evacuated the city and continued to lead the uprising in York, Pennsylvania. Known for his extreme prudence, General Howe chose to spend the winter in Philadelphia rather than go after Washington's army to the north of the city. For Philadelphia, the occupation was catastrophic. Residences and establishments were burned or pillaged. There was a lack of all kinds of supplies. Around the city, there were heaps of the dead. While this was going on, the senior officials resided in opulence in the confiscated mansions of eluded patriots.

On June 18, the city was eventually abandoned, and George Washington dispatched Major General Benedict Arnold, who had not yet committed his act of treason, to assume interim command of the city's forces. Congress soon made its way back. The huge Battle of Monmouth, which involved 25,000 soldiers, was the culmination of the Continental Army's pursuit of Clinton's army as it made its way back to New York. The Continental Army had emerged from Valley Forge at this point. The outcome of the battle, which was practically a draw, saw the British return to New York City and the Continental Army return to White Plains, New York, exactly where they had been two years before before the operations in New Jersey and Philadelphia.

Photo: VISTA.Today

Photo: American Battlefield Trust -

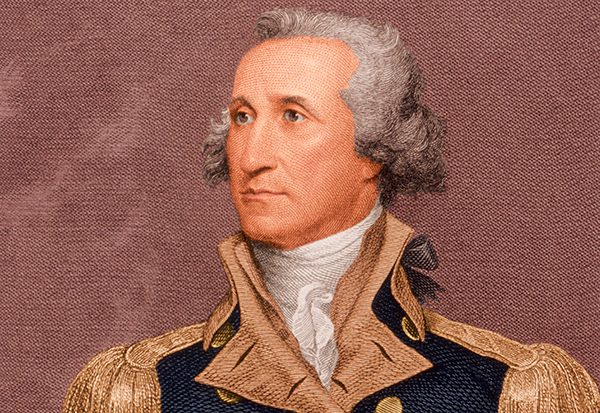

Talking about the facts about the Philadelphia Campaign, facts about George Washington is not to be missed. George Washington was the one who led the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He managed a new army for a brief period of time in 1798 after serving as President of the United States from 1789 to 1797. He was the military figurehead for the American Revolution. On June 14, 1775, Congress gave him the first command of the new Continental Army after the Battles of Lexington and Concord ignited the conflict.The task he undertook was enormous, balancing regional demands, rivalry among his subordinates, morale among the rank and file, attempts by Congress to overly regulate the army's affairs, requests for support from state governors, and an endless need for resources with which to feed, clothe, equip, arm, and move the troops. The numerous state militia groups were typically not under his authority.

After seizing Philadelphia in 1777, Howe eventually made his way back to New York. He gradually understood that North American military strategies would be ineffective in Europe. Armies engaged in direct combat to take control of important cities around Europe. However, the British were still in a weaker position in 1777 despite controlling Philadelphia and New York. After New York, Washington came to the conclusion that the largely unskilled Continental Army was unable to defeat the skilled British army in direct combat. Therefore, he created his own system of warfare that consisted of smaller, more regular skirmishes and shied away from large battles that would have put his entire army at risk. No matter how many cities the British took, as long as he maintained the army together, the fight would continue.

Photo: HistoryExtra

Photo: history.com -

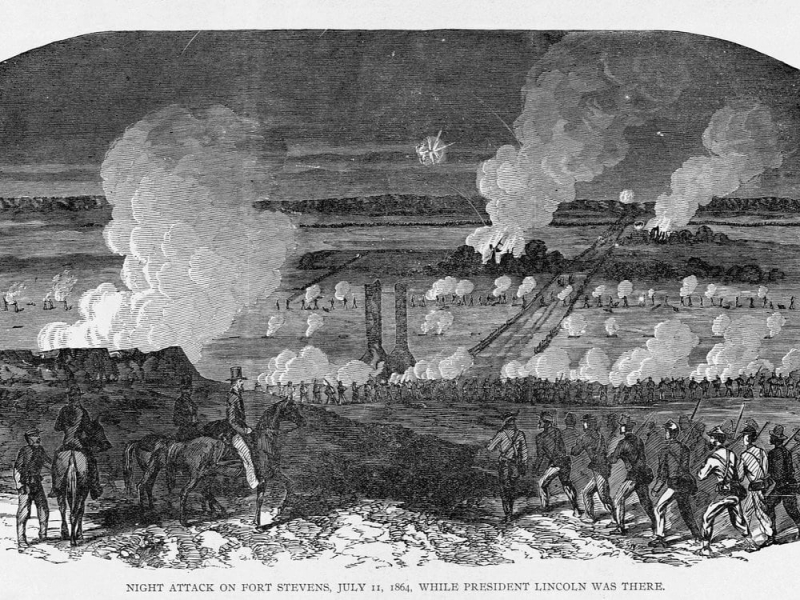

The other two incidents occurred in 1814 when British troops assaulted and set fire to Washington, D.C., and in 1864 when Confederate forces stormed Fort Stevens in Washington, D.C., but were repelled. On August 24, 1814, flames erupted from the unfinished remains of the US Capitol. In reprisal for Americans burning the Canadian capital at York the year before, British forces set fire to this structure, the White House, and much of Washington. According to Joel Achenbach for the Washington Post, among other reasons, the War of 1812 between Britain and its young former colony was sparked by the Royal Navy's practice of "impressing" American men into British service by falsely accusing them of being British subjects.

During the Valley Campaigns of 1864, on July 11 and 12, 1864, forces led by Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early and Union Major General Alexander McDowell McCook engaged in combat in what is now Northwest Washington, D.C. Early's attack, which took place fewer than four miles from the White House, alarmed the American administration, but Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright's reinforcements and Fort Stevens' robust defenses significantly reduced the threat. In the midst of one of its worst heat waves ever, Washington, D.C., prepared for the Confederate onslaught. Both to avoid the heat and the approaching Confederate advance, Congress and influential citizens departed town. President Lincoln, however, chose to stay close to the city, residing with his family at the Soldier's Home in modern-day Northwest Washington, even though a steamer was waiting on the Potomac to pick them up if the situation deteriorated. In the meantime, refugees from neighboring countries started to enter the comparatively safe city.

Photo: CBS News

Photo: Smithsonian Magazine