Top 10 Facts About Trenches Warfare In World War I

Trench warfare is a style of land warfare in which troops are well-protected from enemy small arms fire and are mostly covered from artillery fire by occupying ... read more...lines largely made up of military trenches. Trench warfare became synonymous with World War I (1914–1918) as the Race to the Sea, which began in September 1914, dramatically extended trench use on the Western Front. In this post, Toplist will share some interesting facts about the Trenches Warfare in World War I.

-

When the war on the Western Front began in August 1914, the commanders expected a fight with a lot of troop movement. The Germans had launched a massive offensive over Belgian territory and into France. However, they were adamant about holding on to the land they had so far. Because they were losing ground, the Germans began trench warfare. They would have had to retire and lose land if they had been defeated at the First Battle of Marne.

The French and British troops, on the other hand, were unable to break through this line of defense. Forward-moving techniques, such as head-on infantry attacks, had become obsolete due to the advent of modern gear such as machine guns and heavy artillery. As a result, the Allies dug trenches to provide cover for their own forces. Because they were losing ground, the Germans began trench warfare. They would have had to retire and lose land if they had been defeated at the First Battle of Marne. Instead, they created trenches that made crossing impossible for French and British troops.

Photo: Timeline Express

Photo: War History Online -

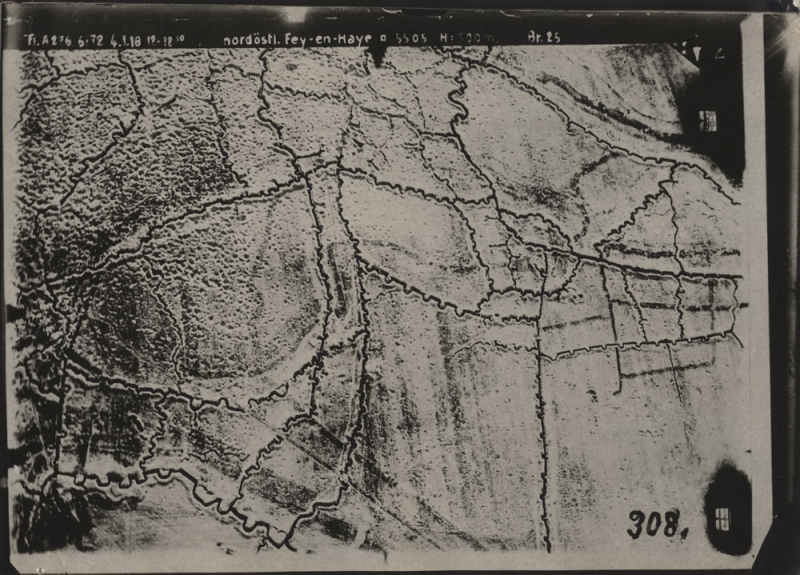

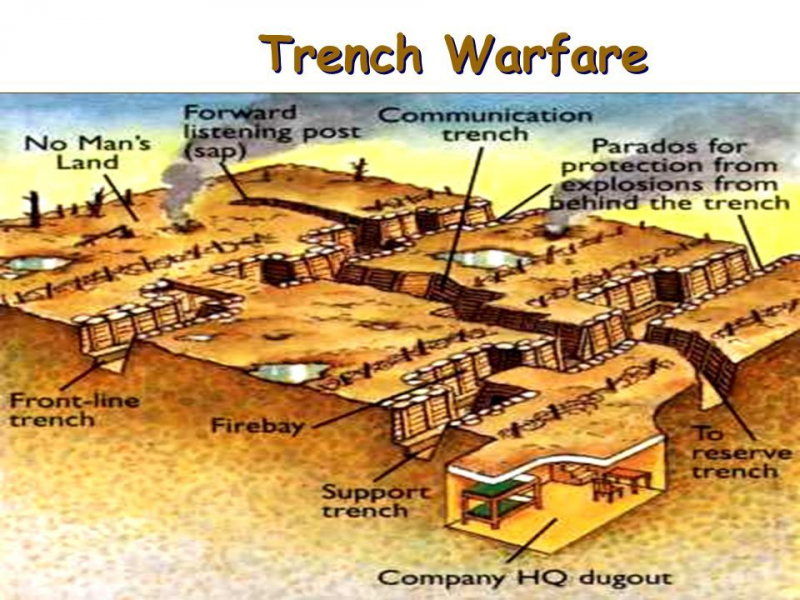

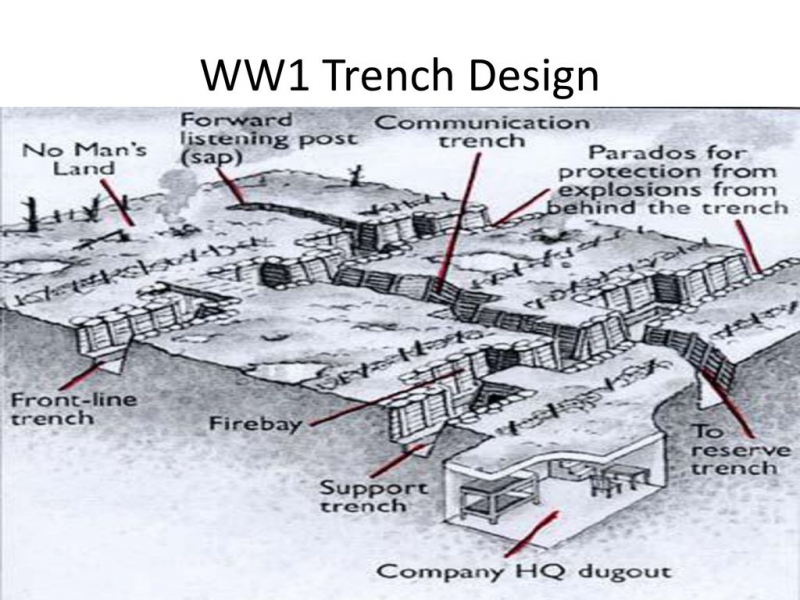

Thousands of miles of trench system were built is the next fact about the trenches warfare in WWI. The trench system began as a temporary measure, but it would become the norm on the Western Front for the next four years, as neither side would be able to decisively penetrate the other's defensive lines. On the Western Front, hundreds of kilometers of trenches were built. Single lines were not like trenches. Multiple layers of trenches, supply trenches, dug outs, forward casualty stations, and so on were used in trench systems.

The Western Front trench system, which was in place from the winter of 1914 to the spring of 1918, finally stretched from Belgium's North Sea coast southward across France, with a bulge outwards to confine the hotly disputed Ypres salient. The system eventually reached its southernmost point in Alsace, near the Swiss border, passing via such French towns as Soissons, Reims, Verdun, St. Mihiel, and Nancy.

There were three types of trenches: firing trenches, which were lined on the enemy's side by steps where defending soldiers could stand to fire machine guns and throw grenades; communication trenches; and "saps," shallower positions that extended into no-man's-land and provided spots for observation posts, grenade-throwing, and machine gun-firing.

Photo: National WWI Museum and Memorial

Photo: Pinterest -

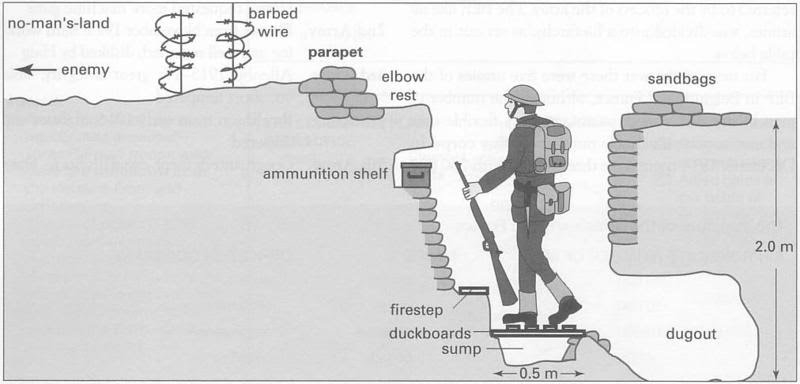

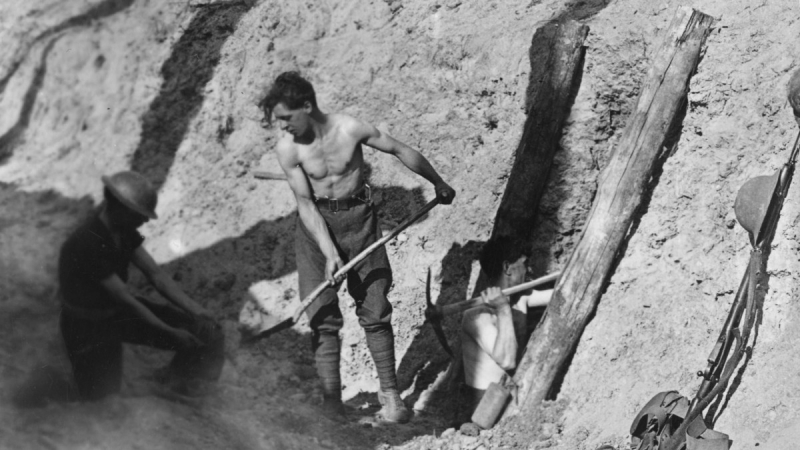

Early trenches were nothing more than ditches dug for the purpose of providing cover during brief wars. However, as the Western Front came to a halt near the end of 1914, the necessity for a more sophisticated system became obvious. The majority of the ditches were constructed according to a set of guidelines. A front wall, sometimes known as a parapet, was constructed facing the adversary and measured around 10 feet in height. Sandbags ran the length of the structure, extending 2 to 3 feet above ground level. The majority of the ditches were roughly 3 meters deep and 1 to 2 meters broad.

For support, they were reinforced with wooden beams. On the ditch, a ledge was constructed that allowed a soldier to walk up and see over the top, generally through a hole between the sandbags. Sandbags were also used to line the back wall, which helped to absorb blasts while also protecting the walls from rain and enemy shelling. Furthermore, machine guns were housed in concrete bunkers built at key locations.

As World War I continued, both sides, particularly the Germans, created trench systems of increasing depth and strength to ensure that the enemy could not break through at any point. The Germans devised a complex defense system based on pillboxes, which are concrete bunkers for machine guns. More barbed wire was installed behind the pillboxes, as well as concrete-reinforced trenches and dugouts to withstand artillery fire. There were other lines of trenches behind these positions that were effectively out of range of the enemy's artillery fire. By 1918, the Germans had built trenches that reached a depth of 14 kilometers.

Photo: Google Site Source: Simple History -

The trenches were constructed in a zigzag style. This is another fact about the trenches warfare in WWI Toplist want to mention. This was done to prevent shrapnel from flying down the trench and to absorb blast. In addition, if an opponent managed to get into the trench, he couldn't just fire along the line. Barbed wire was deployed extensively in front of the front lines, and as and where needed, posing a significant hurdle to any opponents who managed to get through it. If a mortar, grenade, or artillery shell fell into the trench, it would only affect the soldiers in that area, not the rest of the trench. A network of connections trenches were built roughly perpendicular to each of the major lines of trenches, connecting them to each other and to the rear.

These trenches were used to supply food, ammo, fresh troops, letters, and orders. Command posts, advance supply dumps, first-aid stations, cooks, and latrines were all part of the intricate network of trenches. It had machine-gun emplacements to protect against an assault, as well as deep enough dugouts to shelter huge numbers of defending troops during an enemy bombardment.

Photo: MillitaryHistoryNow.com

Photo: TM Terrain -

To support the front line, the support trench, and the reserve trench, most trench systems had at least two additional trench lines. These lines were a few hundred meters apart and connected by connecting trenches, allowing supplies and soldiers to move freely. Dugouts built beneath the trench flooring were found in several trenches. Dugouts occasionally had additional amenities such as mattresses and furniture. The German dugouts were generally more modern, with toilets, electricity, ventilation, and even wallpaper in some cases.

The long-range artillery was stationed some kilometers behind the trench lines, while "no man's land" was the space between the opposing armies' front lines. The region of terrain between the two front lines known as "No Man's Land" was usually between 30 and 250 yards long. Rows of barbed wire, land mines, abandoned or wrecked military equipment, shell holes or artillery craters, dead troops, dead horses, fragments of soldier's uniforms, and what remained of trees and flora may all be found there. There were "Saps," which were listening posts dug out from the front line and into No Man's Land. On both sides of the trenches, compassion would occasionally intervene, and a truce would be called to collect the dead bodies.

Photo: Tes

Photo: Google -

The next fact in the list of facts about the trenches warfare in WWI is the life of soldiers in the trenches. The terrible lives of the men in the trenches are commonly remembered in the aftermath of World War I. Though trench warfare was not a new concept, it was used on a massive scale on the Western Front during the Great War. Soldiers in the trenches faced several problems on a daily basis, making life difficult. As a result of the poor hygienic conditions in the trenches, many soldiers contracted infectious ailments. Soldiers had tasks to do even when they weren't fighting, such as fixing trenches, transferring supplies, cleaning weapons, conducting inspections, and guard duties. One out of every ten men died in the trenches.

Infectious diseases including dysentery, cholera, and typhoid fever were frequent and spread quickly because men fought in close quarters in the trenches, often in filthy conditions. Trench foot is a painful ailment in which dead tissue spreads across one or both feet, requiring amputation in certain cases. It is caused by constant exposure to moisture. Trench mouth, a sort of gum infection, was also a concern, and was linked to the stress of constant bombardment.

The troops were harassed by rats and lice at all hours of the day and night. Oversized rats, bloated on the food and waste of sedentary armies, caused disease and were an annoyance. In 1918, medics discovered that lice was the source of trench fever, which caused headaches, fevers, and muscle pain in the troops.

Photo: ThoughtCo

Photo: BBC -

Heavy rains inundated ditches, making them impassable and dirty. Not only were the soldiers expected to drain the water and repair the damage, but several of them are also believed to have drowned after becoming stranded in the thick, deep mud. As a result of the guys standing in the water for lengthy periods of time, a terrible condition known as "trench foot" developed, which was similar to frostbite. In other cases, this progressed to gangrene, necessitating amputation. The tunnels were generally infested with an unpleasant odor. The trenches smelled of rotting sandbags, cigarette smoke, and poison gas, and many men had not bathed in weeks.

Indeed, the battlefields' flooded trenches and churned landscape are among the most powerful emblems of the First World War. This was especially visible at Passchendaele, which was notoriously flooded due to the rain and the high water table of this low-lying territory, much of which was reclaimed marshland. The bombardment has exacerbated the situation by disrupting normal drainage. Even though pumps were employed to remove water from trenches and dugouts, finding a dry place to rest or sleep was often a struggle. Many soldiers died of trench foot, a fungal condition induced by prolonged exposure to cold water.

Photo: History Hit

Photo: U.S. Army -

"Shell Shock" will be the following fact about the trenches warfare in WWI. Sleeping and resting in trenches was difficult due to the harsh environment. Apart from the unpleasant surroundings and the threat of enemy attack, the sound of shells being fired was a big nuisance. Many soldiers suffered from "shell shock" as a result of the incessant artillery shelling, a debilitating mental disease that may have a direct resemblance to what we now know as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The soldiers themselves developed the term "shell shock." Fatigue, tremor, confusion, nightmares, and poor vision and hearing were among the symptoms. It was frequently diagnosed when a soldier was unable to function for no apparent reason. It had nothing in common with the present diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder because many of the symptoms were physical.

Medical officers were told in 1917 to avoid using the term "shell shock" and to label suspected patients as "Not Yet Diagnosed (Nervous)." The soldier was sent to a psychiatric unit and diagnosed as "shell shock (wound)" or "shell shock (sick)," with the latter diagnosis being provided if the soldier had not been near an explosion. The invalided soldier was transferred to a treatment center in the United Kingdom or France, where he was cared for by neurologists and recovered until he was discharged or returned to the front lines. Officers might have a final period of recuperation before returning to the maw of the war or the business world, recovering strength at a smaller, typically privately funded medical center which were some calm, secluded spot like Lennel House in Coldstream, Scottish Borders region.

Photo: The Conversation

Photo: Quora -

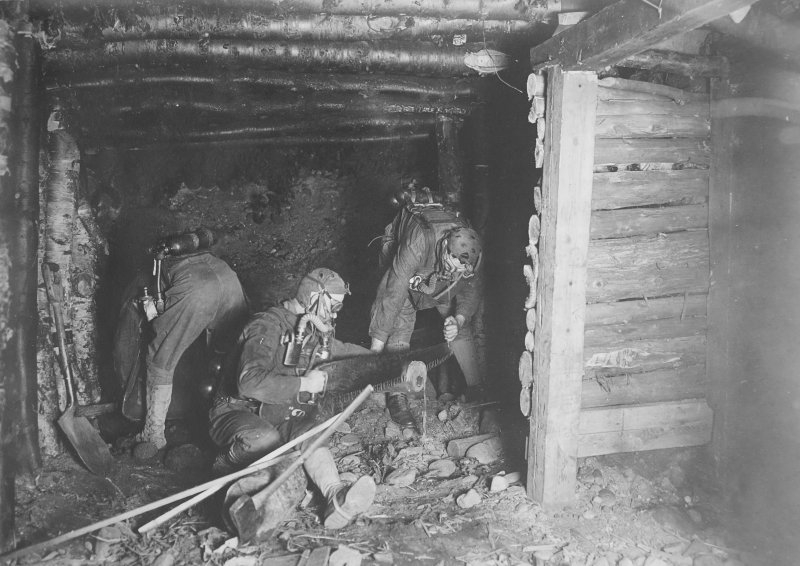

In September 1915, as trench warfare became the norm on the Western Front, Brigadier George Fowke, the British Expeditionary Force's Engineer-in-Chief, recommended a deep mining operation. Fowke had envisioned galleries stretching as far as Grand Bois and Bon Fermier Cabaret on Messines' outskirts, but the longest tunnel was a 660 m (720 yd) gallery to Kruisstraat. Although Fowke and his deputy, Colonel R. N. Harvey had already begun the preliminary work, the design devised by Fowke was formally accepted on 6 January 1916. Several deep mine shafts, dubbed "deep wells," and six tunnels had been started by January. Mining was challenging due to the complex subsurface conditions and distinct ground water levels. Two military geologists, including Edgeworth David, who planned the mine system, assisted the miners in March to overcome the technical challenges.

As a result, a crew of miners built tunnels up to 100 feet below in complete secrecy to plant and detonate mines beneath the enemy's trenches. For months, the miners battled carbon monoxide, tunnel collapse, water, and other hazards, as well as German tunnel diggers who had begun their own mining operations.

Photo: MIchigan Technological University

Photo: History Channel -

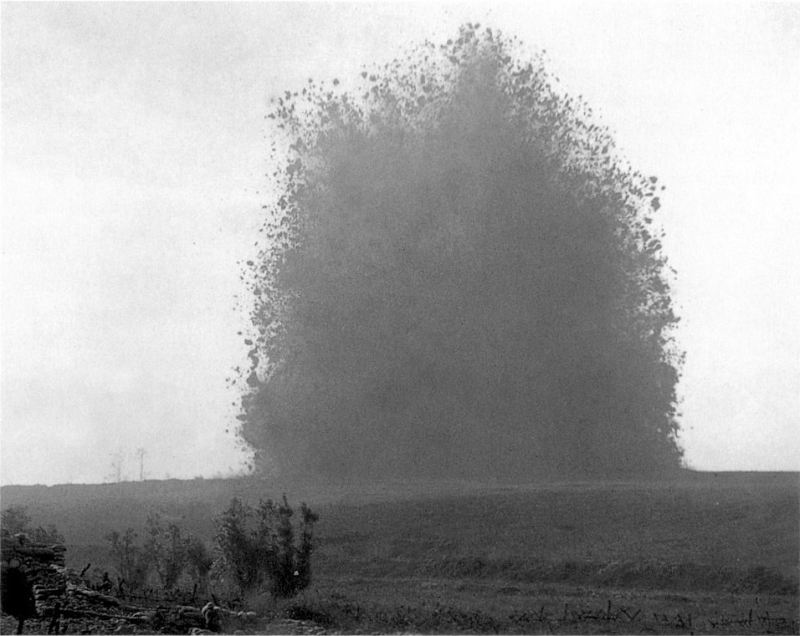

As the war progressed, the Allied tunnel miners began to gain ground on their German counterparts, and their greatest triumph came at Messines Ridge in Flanders. At 3.10 a.m., on June 7, 1917, the mines were set off, signaling the start of the Battle of Messines. In West Flanders, Belgium, 19 mines were blown up along the Messines Ridge. Soldiers detonated the mines, which went off a few seconds apart up and down the length of the slope, blasting geysers of earth, steel, concrete, and bodies into the air and igniting the night sky with orange light.

The joint explosion was one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, with the blast sounding like one of the loudest man-made noises ever heard. The explosions were reportedly detected on a seismograph in Switzerland and were heard by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George in Downing Street, London, from a distance of 241 kilometers. Between Ypres and Ploegsteert. The world seemed to break apart to the Germans, who were stationed in trenches and sleeping in underground bunkers. According to later estimates, up to 10,000 soldiers were killed in the blasts, some of whom were buried alive and many more who were never seen again. The blast knocked men off their feet on the British side of the front. The tremor was misinterpreted as an earthquake in France. This one also ends the list of facts about the trench warfare in WWI.

Photo: Rare Historical Photos

Photo: Wikipedia