Top 7 Major Effects of the Industrial Revolution

In modern history, the Industrial Revolution was the transition from an agrarian and handicraft economy to one dominated by industry and machine production. ... read more...These technological advancements brought about unique working and living arrangements and radically altered society. The 18th century saw the start of this process in Britain, which then expanded to other regions of the globe. Here are the 7 major effects of the Industrial Revolution.

-

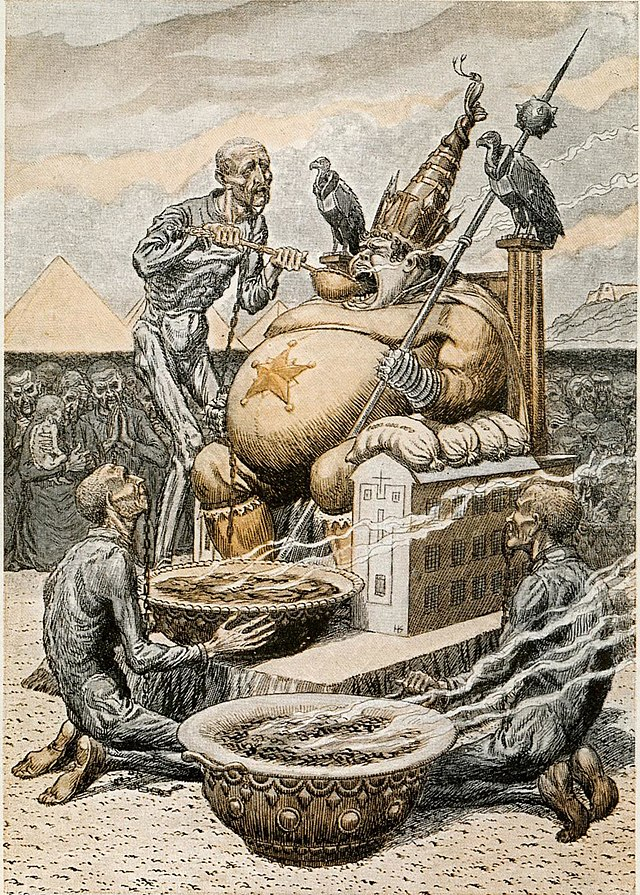

An economic system based on private ownership of the means of production and their use for profit is known as capitalism. Capital accumulation, competitive markets, a price system, private property, the recognition of property rights, voluntary exchange, and wage labor are key features of capitalism. In a capitalist market economy, owners of wealth, property, or the capacity to move capital or the capacity for production control decision-making and investment, although pricing and the distribution of products and services are primarily influenced by competition in goods and services markets.

A group of economists, led by David Hume (1711–1776) and Adam Smith (1723–1790), challenged key mercantilist tenets in the middle of the 18th century, including the notion that the world's wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its wealth by encroaching on that of another state.

Industrialists took the position of merchants as the dominating force in the capitalist economy during the Industrial Revolution, and they contributed to the demise of the traditional handicraft abilities of artisans, guilds, and journeymen. The surplus produced by the expansion of commercial agriculture also spurred more mechanization of agriculture during this time. Industrial capitalism contributed to the growth of the factory manufacturing system, which is characterized by a sophisticated division of labor between and within the various stages of the production process as well as the repetitive nature of the tasks involved, and it ultimately established the dominance of the capitalist mode of production.

The protectionist approach once recommended by mercantilism was subsequently abandoned by industrial Britain. A push to cut tariffs was started in the 19th century by Manchester School adherents Richard Cobden (1804–1865) and John Bright (1811–1889). With the 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws and the 1849 repeal of the Navigation Acts, Britain pursued a less protectionist stance in the 1840s. In keeping with David Ricardo's promotion of free trade, Britain lowered tariffs and quotas.

sites.google.com

en.wikipedia.org -

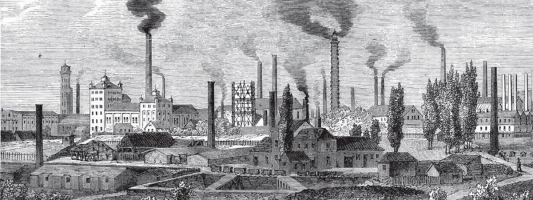

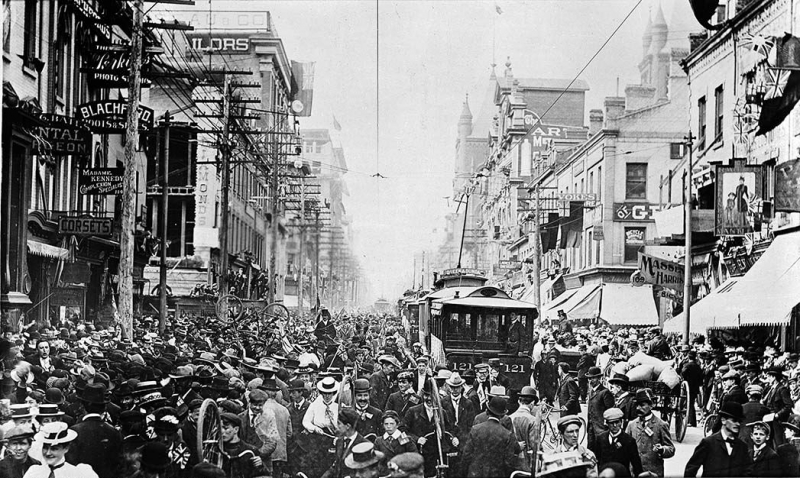

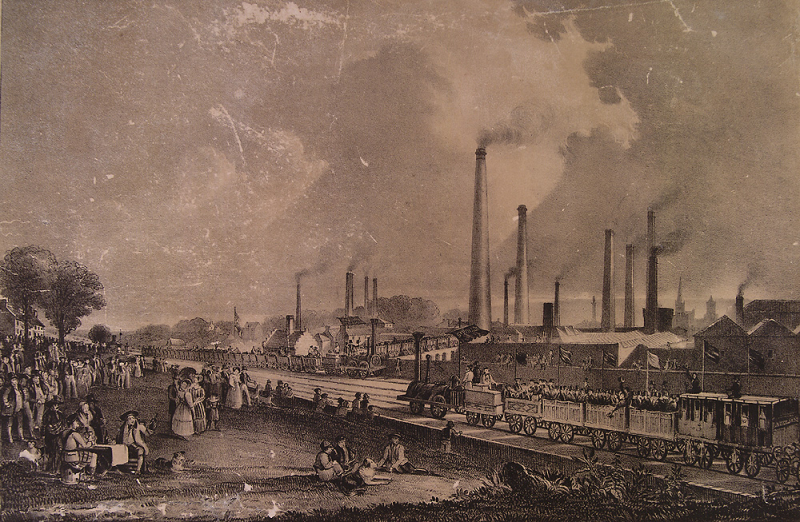

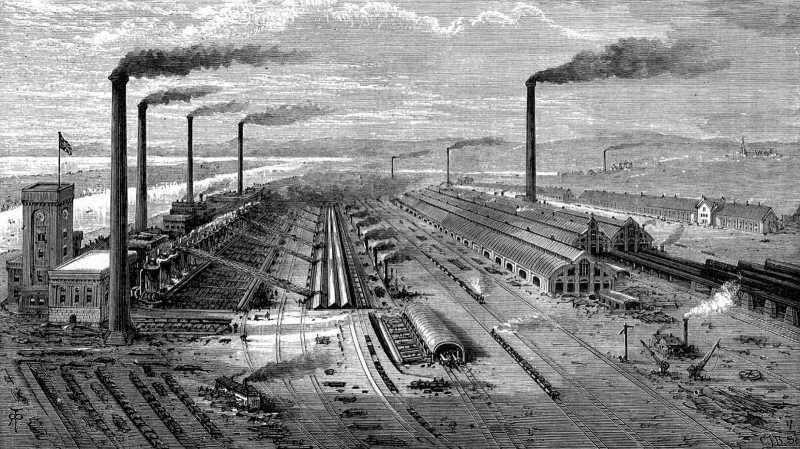

The population transfer from rural to urban regions, the concomitant decline in the number of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adjust to this transition are all referred to as urbanization. As one of major effects of the Industrial Revolution, urbanization is primarily the process by which towns and cities are created and enlarged as more people move into urban centers to live and work.

This relationship was finally shattered with the beginning of the British agricultural and industrial revolution in the late 18th century, and over the course of the 19th century, both through continued migration from the countryside and due to the tremendous demographic expansion that occurred at that time, there was unprecedented growth in the population of cities.

In England and Wales, the percentage of the population residing in cities with a population of more than 20,000 increased from 17% in 1801 to 54% in 1891. By using a broader definition of urbanization, it can be seen that whereas the urbanized population in England and Wales made up 72% of the total in 1891, it was only 37% in France, 41% in Prussia, and 28% in the United States.

Workers flocked to the new industrial cities like Manchester and Birmingham that were experiencing a boom in commerce, trade, and industry as they were liberated from working the land due to improved agricultural production. Growing international trade also made it possible to import frozen meat from South and Australasia and cereals from North America. Cities also grew spatially as a result of the development of public transportation networks, which made it easier for the working class to commute over larger distances to the city center.

According to Britannica, in 1801, about one-fifth of the population of the United Kingdom lived in towns and cities with 10,000 or more inhabitants. Two-fifths of the population had reached this level of urbanization by 1851, and more than half of the population could be considered urbanized if smaller towns with a population of 5,000 or more were taken into account. The first industrial society in the world had also developed into the first one that was genuinely urban. By 1901, the year of Queen Victoria’s death, the census recorded three-quarters of the population as urban (two-thirds in cities of 10,000 or more and half in cities of 20,000 or more) (two-thirds in cities of 10,000 or more and half in cities of 20,000 or more). As industrialization advanced, the pattern was replicated first on a European and later global level.

commons.wikimedia.org

agustinadearagonschool.blogspot.com -

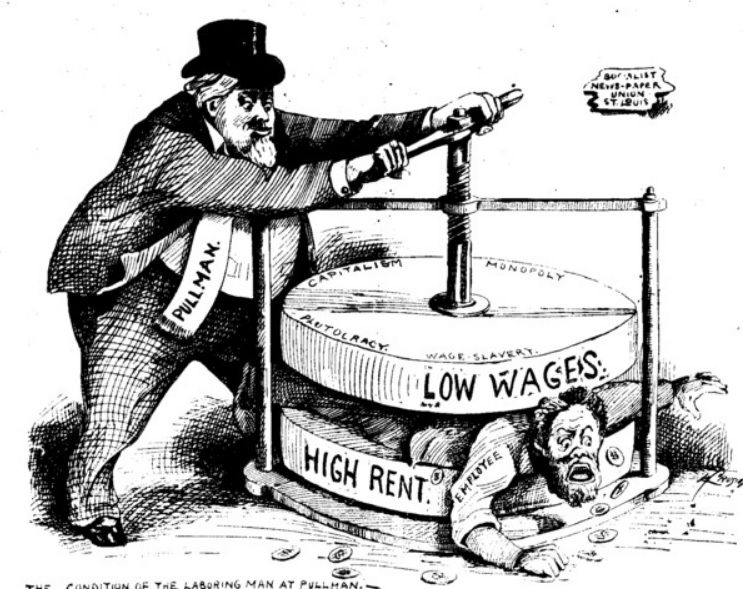

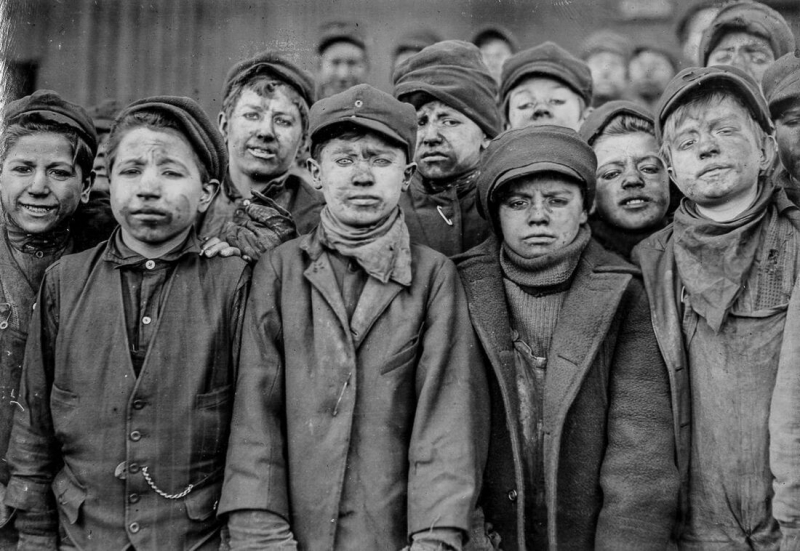

One of major effects of the Industrial Revolution is the labor exploitation. Significant societal changes were brought about by the Industrial Revolution's economic and technological features. The greater population density in compact locations allowed the new industries to access a vast pool of laborers, and the larger labor force allowed for ever-increasing specialization. Numerous industrial employees in Europe were living in the most appalling conditions by the 19th century, numbering in the thousands. It initially appeared to make the poverty and misery of workers worse. They were forced to rely on expensive production tools that few people could afford to purchase for employment and survival. There was little job security because of a vast labor pool and frequent worker displacement brought on by technical advancements. Lack of laws and rules protecting workers resulted in long hours for meager pay, living in filthy tenements, and occupational abuse and exploitation.

Immigrants from rural areas flocked to cities lured by the prospect of gainful employment only to discover that they were compelled to live in overcrowded, dirty slums filled with rats, sickness, and other vermin. The streets of the newer cities were frequently laid out in grid patterns that were intended for commerce rather than human needs like privacy and recreation, yet allowed these towns to grow endlessly.

According to Beck, many socialist movements that aimed to improve the living and working conditions of industrial workers formed. For instance, both Marxism and utopian socialism aimed to end the exploitation of workers by owners and improve social balance. The concept of labor unions also gained popularity during this time in industrial societies. Workers established unions and utilized them to agitate for a range of causes, such as reduced working hours, more income, secure working conditions, access to healthcare, and basic education.

Many of them succeeded in achieving these objectives by putting pressure on the government to intervene and enact laws governing various facets of industrial operations. For instance, the British government created legislation restricting child labor as the Industrial Revolution gained momentum. The Factory Acts of 1819 set a 12-hour maximum workweek for British children. Children under the age of nine were no longer permitted to work, and those above the age of 13 were only permitted to work for a maximum of nine hours per day by 1833. More triumphs for the working class were won by the labor movement in the shape of minimum wage laws, hourly limits, required lunch breaks, and health and safety standards.

historycrunch.com

historycrunch.com -

The Industrial Revolution impacted significantly the standards of living. The real impact of the Industrial Revolution, according to some economists like Robert E. Lucas, Jr., was that "for the first time in history, the standards of living of the masses of ordinary people have begun to undergo sustained growth. Nothing remotely like this economic behavior is mentioned by the classical economists, even as a theoretical possibility." Others, however, contend that although the Industrial Revolution saw an unprecedented increase in the economy's overall productive powers, the majority of people's living standards did not improve significantly until the late 19th and early 20th centuries and that in many ways, early capitalism caused workers' living standards to decline. For instance, investigations have revealed that between the 1780s and 1850s, real wages in Britain only climbed by 15% and that the country's life expectancy did not start to significantly rise until the 1870s. The population's average height also decreased during the Industrial Revolution, suggesting that their nutritional status was deteriorating as well. The cost of food was rising faster than real salaries.

The life expectancy of children significantly rose during the Industrial Revolution. From 74.5 percent in 1730-1749 to 31.8 percent in 1810–1829, the proportion of London-born children who passed away before the age of five fell.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, economic and social historians vigorously disputed the consequences of the industrial revolution on living standards. The academic consensus that the majority of the population, who were at the bottom of the social ladder, suffered serious decreases in their living conditions, was later established by a series of 1950s writings by Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila V. Hopkins. The wages of workers significantly increased between 1813 and 1913.

vox.com

historycrunch.com -

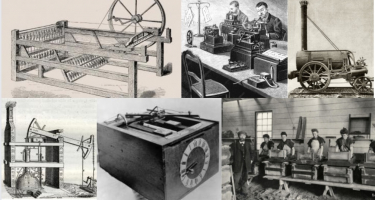

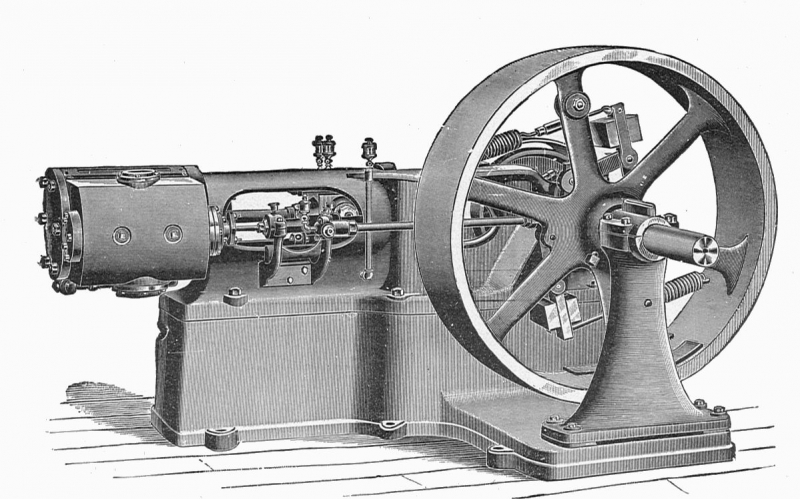

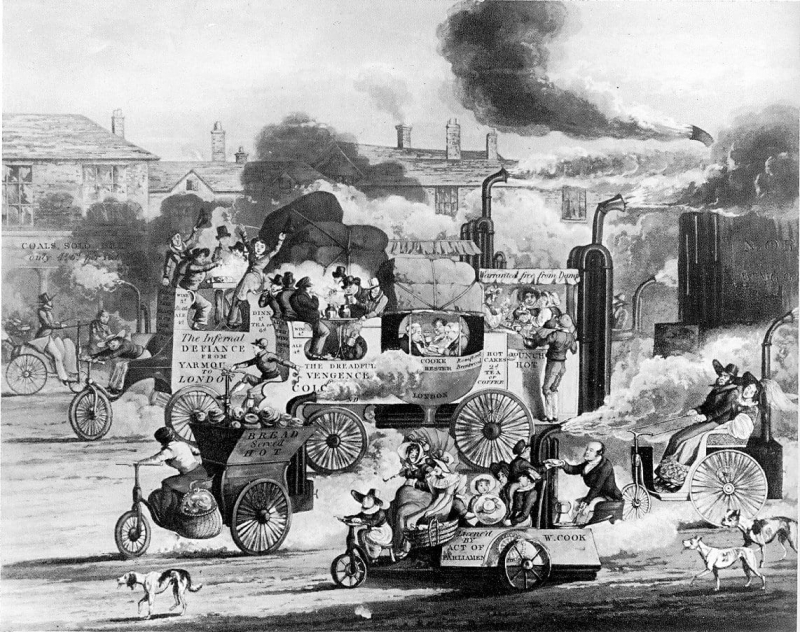

The start of the Industrial Revolution is intimately associated with a number of technological innovations that began in the second half of the 18th century. The following advances in significant technologies had been made by the 1830s.

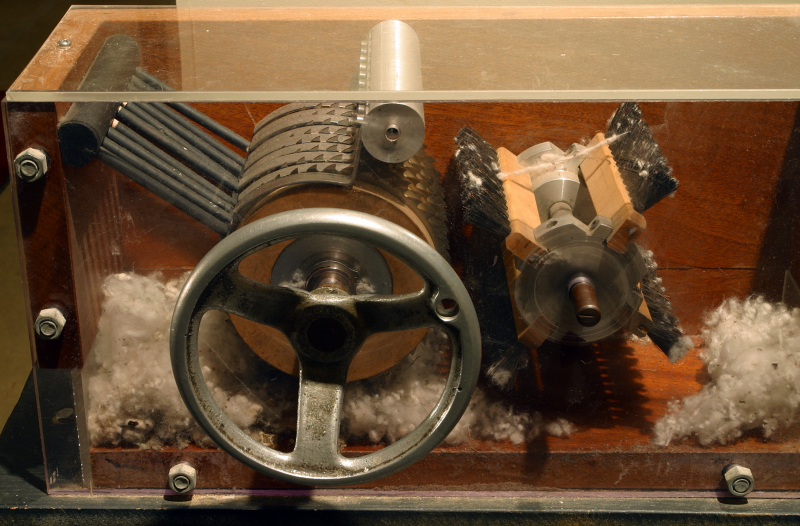

Mechanized cotton spinning driven by steam or water increased a worker's output in the textiles industry by a factor of about 500. A worker's output was increased by a factor of nearly 40 thanks to the power loom. The cotton gin significantly boosted cotton seed removal productivity by a factor of 50. Wool and linen spinning and weaving saw significant increases in productivity as well, though not to the same extent as cotton. Steam engines became more efficient, requiring between one-fifth and one-tenth less fuel. The conversion of stationary steam engines to rotational motion allowed for their usage in industry. The high-pressure engine was appropriate for transportation because it had a high power-to-weight ratio. After 1800, steam power had a tremendous increase.

The cost of fuel for the manufacturing of pig iron and wrought iron was significantly reduced by substituting coke for charcoal. Coke usage also made it possible to build larger blast furnaces, which led to cost savings. A significant rise in iron production was made possible by the steam engine's ability to directly power blast air (by pumping water to a waterwheel) around the middle of the eighteenth century. In use since 1760 is the cast iron blowing cylinder. Later, it was enhanced by making it dual-acting, enabling higher blast furnace temperatures. Puddling was a less expensive method than finery forging for producing structural quality iron. In comparison to hammering wrought iron, the rolling mill was fifteen times faster.

The first machine tools were also created during the Industrial Revolution, along with numerous other technological innovations. These comprised the milling machine, cylinder boring machine, and screw-cutting lathe. Although it took many years to develop efficient methods, machine tools made it possible to make quality metal parts on a budget.

en.wikipedia.org

thinglink.com -

One of major effects of the Industrial Revolution is that it had negative impacts on the environment. The environmental movement got its start as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution's rising levels of smoke pollution in the atmosphere. After 1900, the high volume of industrial chemical discharges added to the increasing load of untreated human waste. The advent of huge factories and the concurrent enormous growth in coal consumption led to an unparalleled degree of air pollution in industrial hubs. The British Alkali Acts, passed in 1863 to control the harmful air pollution (gaseous hydrochloric acid) released by the Leblanc process, which is used to generate soda ash, were the first extensive, modern environmental legislation. To stop this pollution, four sub-inspectors and an Alkali inspector were hired.

The Alkali Order of 1958, which put under regulation all significant heavy businesses that released smoke, grit, dust, or fumes, marked the culmination of the inspectorate's constantly expanding responsibilities.

Between 1812 and 1820, produced gas production started in British cities. The method employed resulted in very hazardous sewage being deposited into rivers and sewers. Numerous nuisance cases were filed against the gas companies. They frequently lost and changed their worst habits. In the 1820s, the City of London regularly accused gas companies of contaminating the Thames and its fish. Finally, in order to control toxicity, Parliament drafted business charters. Around 1850, the industry arrived in the US, bringing with it lawsuits and pollution.

Local experts and reformers in industrial cities took the lead in identifying environmental degradation and pollution and launching grass-roots initiatives to demand and enact reforms, especially after 1890. Water and air pollution were typically given top concern. One of the first environmental NGOs, the Coal Smoke Abatement Society was established in Britain in 1898. Sir William Blake Richmond, an artist, founded it after becoming dissatisfied with the gloom that coal smoke created. Despite prior laws, the Public Health Act of 1875 mandated that all stoves and furnaces must expel their own smoke. Provisions against factories that released a lot of black smoke were also included. The Smoke Abatement Act, passed in 1926, expanded the scope of this law's restrictions to cover other emissions, including soot, ash, and grit particles, and also gave local governments the authority to enact their own rules

en.wikipedia.org

re-thinkingthefuture.com -

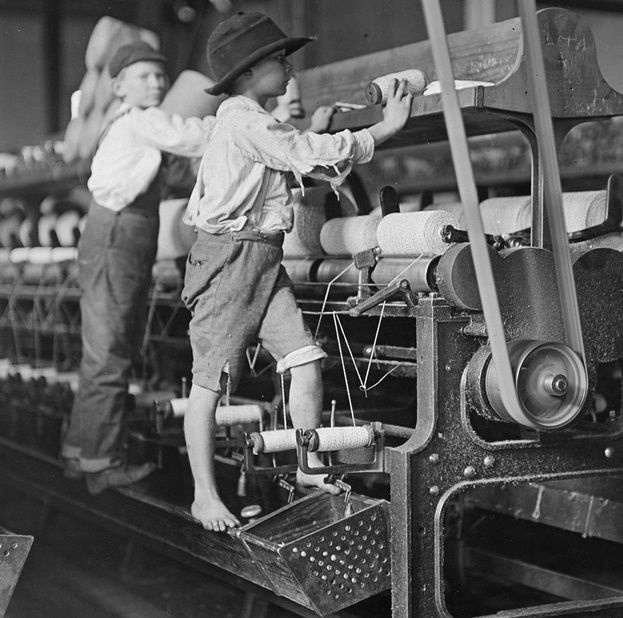

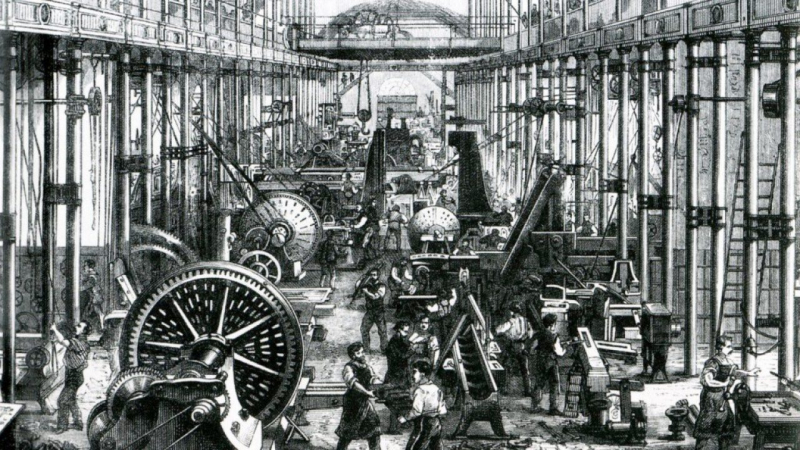

Another effect of the Industrial Revolution is that it had an impact on the modern factory system. The majority of the workforce worked in agriculture prior to the Industrial Revolution, either as independent farmers, landowners, tenants, or landless agricultural laborers. Families were accustomed to spinning yarn, weaving cloth, and creating their own clothing. For market output, households also spun and woven. The majority of the cotton cloth used in the world at the time was manufactured in India, China, and various Middle Eastern and Asian regions, while Europeans produced wool and linen goods.

By the 16th century, the putting-out system—often referred to as a cottage industry—which allowed farmers and town residents to create things for a market in their homes—was being used in Britain. Spinning and weaving were typical putting-out system products. Typically, merchant capitalists supplied the raw materials, paid employees by the piece, and handled the selling of the products. Poor quality and employee theft of supplies were frequent issues. The putting-out approach had additional drawbacks related to the logistical effort required for obtaining, distributing, and taking up finished goods. Cottagers could afford some early weaving and spinning equipment, such as a 40-spindle Jenny that cost about six pounds in 1792. Because later machinery like spinning frames, spinning mules, and power looms was costly (especially if they were powered by water), capitalism came to control companies.

During the Industrial Revolution, unmarried women and children, including many orphans, made up the majority of the workforce in textile factories. On average, they put in 12 to 14 hours a day, with just Sundays off. Women frequently accepted seasonal jobs in factories during the slow seasons of farming. It was challenging to find and keep employees because of inadequate transportation, long hours, and low compensation. Many people who were forced to work in factories included displaced farmers and agricultural workers who had nothing to sell but their labor.

populationeducation.org

australiancurriculumlessons.com.au