Negative impacts on the environment

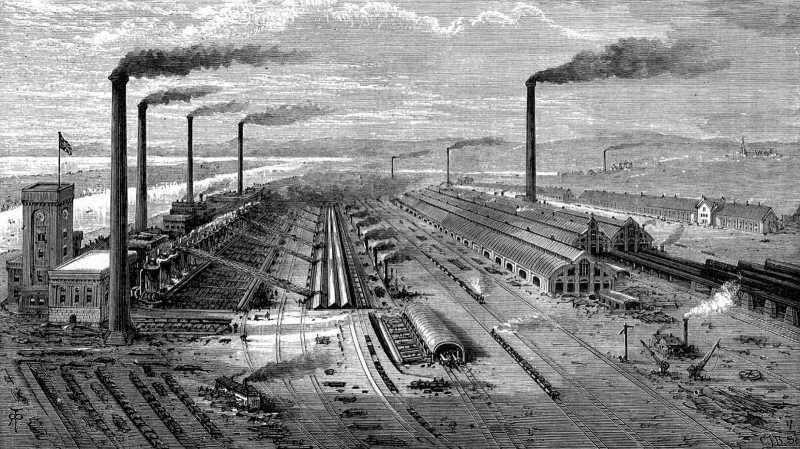

One of major effects of the Industrial Revolution is that it had negative impacts on the environment. The environmental movement got its start as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution's rising levels of smoke pollution in the atmosphere. After 1900, the high volume of industrial chemical discharges added to the increasing load of untreated human waste. The advent of huge factories and the concurrent enormous growth in coal consumption led to an unparalleled degree of air pollution in industrial hubs. The British Alkali Acts, passed in 1863 to control the harmful air pollution (gaseous hydrochloric acid) released by the Leblanc process, which is used to generate soda ash, were the first extensive, modern environmental legislation. To stop this pollution, four sub-inspectors and an Alkali inspector were hired.

The Alkali Order of 1958, which put under regulation all significant heavy businesses that released smoke, grit, dust, or fumes, marked the culmination of the inspectorate's constantly expanding responsibilities.

Between 1812 and 1820, produced gas production started in British cities. The method employed resulted in very hazardous sewage being deposited into rivers and sewers. Numerous nuisance cases were filed against the gas companies. They frequently lost and changed their worst habits. In the 1820s, the City of London regularly accused gas companies of contaminating the Thames and its fish. Finally, in order to control toxicity, Parliament drafted business charters. Around 1850, the industry arrived in the US, bringing with it lawsuits and pollution.

Local experts and reformers in industrial cities took the lead in identifying environmental degradation and pollution and launching grass-roots initiatives to demand and enact reforms, especially after 1890. Water and air pollution were typically given top concern. One of the first environmental NGOs, the Coal Smoke Abatement Society was established in Britain in 1898. Sir William Blake Richmond, an artist, founded it after becoming dissatisfied with the gloom that coal smoke created. Despite prior laws, the Public Health Act of 1875 mandated that all stoves and furnaces must expel their own smoke. Provisions against factories that released a lot of black smoke were also included. The Smoke Abatement Act, passed in 1926, expanded the scope of this law's restrictions to cover other emissions, including soot, ash, and grit particles, and also gave local governments the authority to enact their own rules