Top 10 Odd Artifacts Housed in the Smithsonian

With so many facilities and a large collection, it makes sense that the Smithsonian holds some rather unusual artifacts. Some of them are on view in the ... read more...various museums. Others are kept at the Smithsonian Museum Support Center in Suitland, Maryland, known as "Nation's Attic." The general public is not permitted access to the Support Center. Others have been deemed unfit for public display, while some of the pieces kept there are being prepared for later display in the museums. However, the Smithsonian and its affiliates' museums and vaults are filled to the brim with curiosities. Here are ten Artifacts Housed in the Smithsonian.

-

The renowned behaviorist BF Skinner created a pigeon-operated missile guidance system for use during World War II. Through conditioning, the pigeons were taught to peck at particular images they saw while in flight. The pecks turned on sensors, which guided the missile in the direction of the target. Though Skinner claimed to have made substantial headway training the pigeons, the program was ultimately abandoned in October 1944 without having conducted any successful testing. He reproached the military for not treating the undertaking seriously.

The Smithsonian has a nose cone created by Skinner and his collaborators. Three distinct compartments, one pigeon each, made up Skinner's design. The lateral, longitudinal, and vertical axes of flight were each controlled by a different pigeon. Despite having obvious flight expertise, the pigeons frequently overreacted to stimuli during the studies by either pecking excessively or not at all. In one experiment, a pigeon pecked more than 10,000 times in a 45-minute period, according to Skinner's records. Although the Smithsonian's nose cone is not currently on public display, pictures of the experimental guidance system can be found online.

Image by Tim Mossholder via pexels.com

Image by Valeria Boltneva via pexels.com -

Theodore Roosevelt refused to personally shoot a bear that had been run to exhaustion on a hunting trip in 1902, but he did order that others put the animal to death (or so the story goes). Depending on the political views of the reporters and cartoonists, he was either praised or lampooned when the media learnt of the occurrence. Posters, brochures, and editorial cartoons all featured images of "Teddy's Bear."

A businessman by the name of Morris Michtom made a little stuffed bear toy modeled after the cartoon characters and showed it in his store under the name "Teddy." The Ideal Novelty and Toy Company was founded by Michtom in 1907 as a result of the success of bears that followed those of the original. The Ideal Novelty and Toy Company was founded by Michtom in 1907 as a result of the success of bears that followed those of the original. Roosevelt, who hated the term "Teddy," responded positively when Michtom asked for permission to use Teddy's Bear.

The Roosevelt family was contacted by officials of the Ideal Toy Company in the early 1960s in an effort to persuade them to appear for a promotional photo with one of the original bears. Teddy Roosevelt's grandson Kermit eventually decided to let his kids take pictures with the bear before giving it to the Smithsonian after first refusing. The bear was well-liked by Kermit's kids, who resisted giving it away. Family lore claims that they kept the toy from their parents. Persuasion or perhaps parental authority won out. The Roosevelt family donated the first Teddy Bear to the Smithsonian in January 1964. The Museum of American History is where it is kept.

Image by Marina Shatskikh via pexels.com

Image by suntorn somtong via pexels.com -

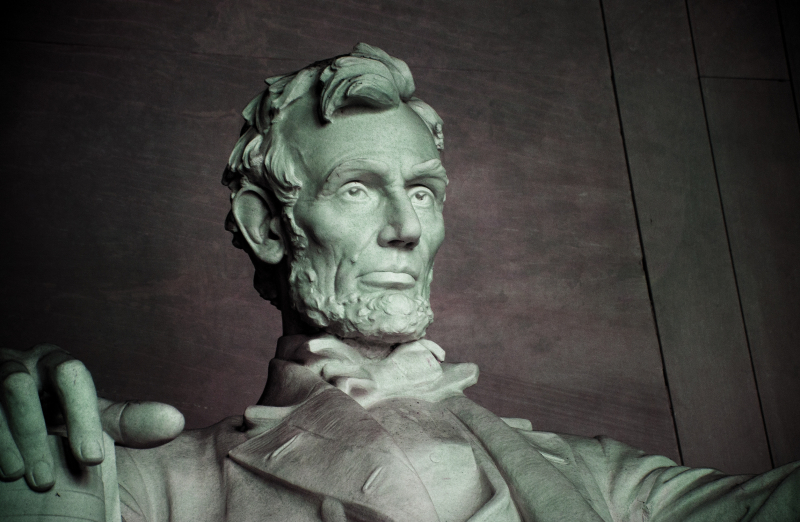

Contrary to popular myth, there is no death mask from the assassinated Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln twice sat for facial molds to be taken during his lifetime in order to make a life mask. The first was established in 1860, while Lincoln negotiated for the Republican Party's nomination to run for president. As a result, the Lincoln mask shows him without a beard.

Lincoln did not enjoy the treatment, according to its originator, a sculptor by the name of Leonard Volk, who later revealed that Lincoln found it unpleasant, taxing, and slightly painful. Lincoln still praised the resulting life mask, calling it "the animal itself" in a self-deprecating manner. In February 1865, after being re-elected and while awaiting his second inauguration, Lincoln took the second mask.

Despite the fact that Lincoln was still alive when he sat for the cast to be formed, the second mask, which was constructed by Clark Mills, is frequently referred to as the President's death mask. The Smithsonian is the owner of the Mills mask. Although it is not currently on display to the public, pictures of the mask can be found online.

Theodore Mills, the artist's son, gave the mask to the Smithsonian in 1889. After additional bronze castings from the previous Volk mask molds were produced, the Smithsonian received the molds in 1886. The Metropolitan Museum in New York has one such casting on display, which clearly depicts a younger Lincoln.

Image by Pixabay via pexels.com

Image by Pixabay via pexels.com -

Even though it's difficult to imagine more than 50 years later, the original Star Trek series was a ratings failure and barely lasted three years. However, its influence on the entertainment sector is almost incalculable. It also made a huge contribution to American slang by coining expressions like "beam me up," "I'm a doctor, not a" and, of course, "Warp speed."

Phasers and photon torpedoes were also new weaponry that were introduced. Large, strong phasers might be able to destroy cities, asteroids, and other objects. They could also be small, portable weapons that just stun an opponent rather than kill them. In order to keep people warm, they may also be used to heat rocks or other useful objects.

Several phasers from Star Trek TOS (The Original Series) are kept by the Smithsonian Institution and are frequently displayed in their touring exhibits. The USS Enterprise original model, which was not housed alongside the Smithsonian's other television relics, was used to film the series in the 1960s. The replica was suspended from the ceiling of the Air & Space Museum's gift shop for many years.

It was moved, a vision of the future committed to history, to the Boeing Milestones of Flight Exhibit at the Air & Space museum after restoration. It and other neighboring exhibits were taken down in October 2019 because the hall was being renovated; however, after the work is over, it will be available for public viewing once again

Image by Tima Miroshnichenko via pexels.com

Image by Martin Lopez via pexels.com -

During his brief life (1971–1984), David Philip Vetter rose to fame as the "child in the bubble." David was placed in a confined, hygienic environment from birth because of a congenital condition known as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), and he lived there for the majority of his life. He was eventually given access to a mobile, sterile environment that looked like a space suit and allowed for some limited movement outside of his restricted environment. NASA gave him a new suit when he outgrew the first, but he apparently never used it. The American Experience claims that David only ever used the original costume seven times since he didn't like it. He passed away at the age of 12 from lymphoma.

During David's brief life, there was a lot of debate, but it subsided once he passed away in 1984. Some believed the treatment he received was less an effort to treat his crippling sickness and more a research tool. He eventually turned into the target of crude humor from stand-up wags. The Smithsonian has a sizable collection of items related to his experience, including letters from doctors, pictures, medical tools, and NASA-provided suits. Despite not being on display to the public, they are kept at the Museum of American History. The majority of the objects are viewable online.

Image by Pixabay via pexels.com

Image by Pixabay via pexels.com -

Before the Smithsonian Institution, the Patent Office in Washington, D.C., housed a well-known museum of American artifacts. The museum, which is officially called the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, attracted visitors who were interested in its numerous patent models and other items.

Abraham Lincoln enjoyed going to the Patent Office while he was president, frequently with his younger kids. John Varden, a museum employee, started gathering hairpieces from notable figures around 1850, including General Winfield Scott, Sam Houston, and all the Presidents from George Washington to Franklin Pierce. Varden placed newspaper ads requesting donations from people carrying hairpieces. The locks were mounted on a plaque and put on display at the museum in 1853.

Varden made a new plaque that held the presidential hairs and removed them from the original one around 1855. The Smithsonian still holds the hair plaques after receiving them from the Patent Office in 1883 along with a large portion of its museum collections. They can be viewed online, just like a lot of the collection, and are housed in the Museum of American History. The results of DNA testing on the locks have not been released, so it is unclear if they truly belong to the men they represent.

Image by Jess Loiterton via pexels.com

Image by Seva Kruhlov via pexels.com -

All in the Family, a sitcom from the 1970s, clearly couldn't be produced today. Archie Bunker, the show's protagonist, was blatantly racist, anti-Semitic, misogynistic, anti-liberal, and extremely humorous. Carroll O'Connor played the role of Archie, who parodied the traditional blue-collar, conservative family guy of the day. His wife Edith, daughter Gloria, and son-in-law Mike put up with his rants during which the latter was frequently called a "meathead." Archie also used a disparaging term for people of Polish heritage to describe his son-in-law. Although the show was as politically incorrect as it was humanly possible to be, it has consistently ranked among the top 10 television shows.

Archie's chair and his reaction to anyone having the effrontery to sit in it were the subject of a running joke on the program. He always gave the same response, telling the person to get up from their chair and frequently adding an expletive. Archie frequently sat in his chair and offered his opinion on current events. Edith sat in the chair across from Archie's, which was obviously less comfortable. A little table that typically held a can of beer for Archie's delight and an ashtray for his cigar separated the two. All of them are on display in the Smithsonian's Museum of American History, exactly as they did for many years on the All in the Family set.

Image by Harmoor Furniture via pexels.com

Image by Tima Miroshnichenko via pexels.com -

Public service announcements (PSAs), which are typically a little depressing, brought a comedic approach to a serious issue in 1985. The issue was that American drivers weren't wearing seatbelts. The introduction of Vince and Larry, crash test dummies, to highlight the dangers of not using a seatbelt while in a collision provided the humor. The tagline of the Vince and Larry PSAs was, "You can learn a lot from a dummy." In the late 1980s, the tagline and the commercials went viral across America. Vince and Larry rose to fame.

The costumes for the actors Vince and Larry were put in storage after the campaign ended in 1998. The Smithsonian conducted a hunt to find the dummies in the first decade of the twenty-first century with the intention of acquiring them for their collection. A display on the development of car safety was unveiled in 2010 at the National Museum of American History. It featured early seatbelts, airbags, actual crash test dummies and their sensors, as well as other comparable tools. Vince and Larry, two former comic book stars who are now Smithsonian Institution relics, are seated among them.

Image by Ruca Souza via pexels.com

Image by James Frid via pexels.com -

Numerous relics from America's military history are housed in the National Museum of American History of the Smithsonian, both on exhibit and in its storage vaults. The stuffed body of a carrier pigeon named Cher Ami is one of the items on display. In 1917–18, Cher Ami, sometimes known as Dear Friend, served in France with the American Expeditionary Force. In both the First World War and the subsequent, far larger World War, pigeons played a significant role in communications and signal operations. Pigeons had been used to transmit communications before the Americans arrived in France, to the point where the Germans introduced falcons to hunt them down.

Cher Ami performed her duty admirably, delivering 12 messages before suffering an injury while making another trip. The pigeon received a buckshot from an enemy marksman, losing an eye and suffering severe leg injuries, but it nevertheless made it to its destination with the message capsule still within. Cher Ami passed away from his wounds. For its final mission, which contributed to the survival of nearly 200 soldiers, the French gave the bird the Croix de Guerre. Later, the bird was preserved. The Smithsonian's museums and libraries host a number of displays recognizing the use of animals in warfare, including Cher Ami.

Image by Vicky Deshmukh via pexels.com

Image by Castorly Stock via pexels.com -

Hans Langseth, an Iowa farmer of Norwegian descent, entered a beard-growing competition when he was 19 years old. It is uncertain if he won the competition, but he decided to keep growing his beard afterward. Hans reinforced and gave his beard more substance as it grew by coiling it as it grew. As he got older, Hans traveled the nation as a sideshow entertainer, performing at circuses and fairs. He carried the beard between appearances in his pockets or bag, wrapped around a corncob. The beard still has corn in it, according to Smithsonian officials. By 1922, a club calling itself the Whiskerinos had measured Langseth's beard to a length of 17 feet, making it the longest in America.

1927 saw Hans's passing. He requested that his beard be removed, but otherwise left in tact. Before his son gave it to the Smithsonian, it spent many years in his family's custody, packaged and stored. From 1967 until it was taken out and kept in the National Museum of Natural History, it remained there on exhibit. Although Langseth's relatives have occasionally had access to it, it is still in storage today. The curators, who keep the beard as part of their research on the human body collection, decide if and when to put it back on display.

Image by Bruno Salvadori via pexels.com

Image by Mathew Thomas via pexels.com