He advocated for slavery

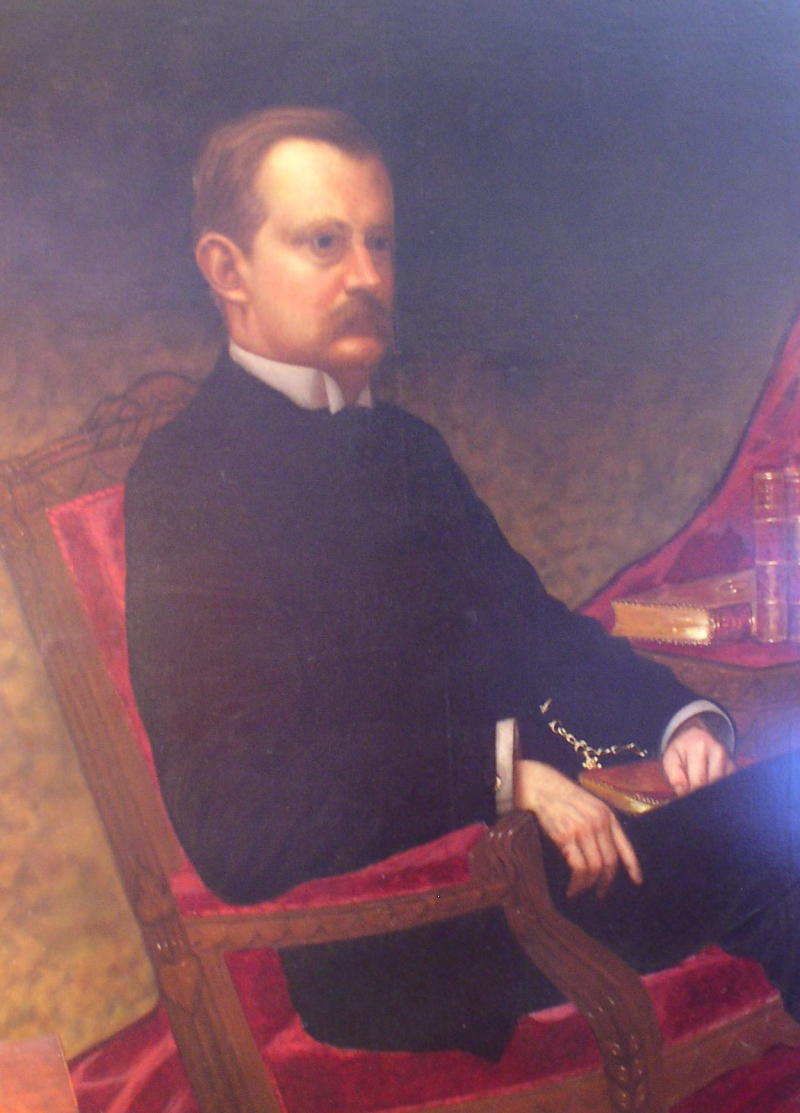

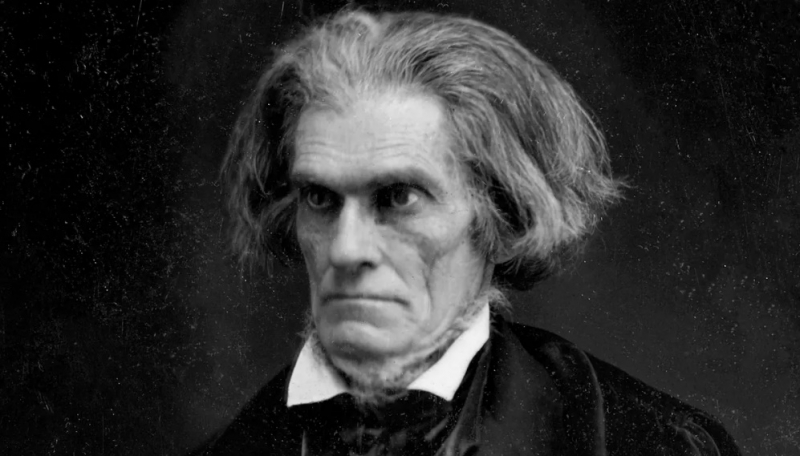

It is a fact that he advocated for slavery. Calhoun became known as the "cast-iron man" later in life for his staunch defense of white Southern beliefs and customs. His republicanism emphasized support for slavery and minority state rights, as exemplified by the South. In Fort Hill, South Carolina, he possessed scores of slaves. Slavery, Calhoun claimed, was a positive good that benefited both slaves and owners, rather than a necessary evil. To defend minority rights from majority control, he advocated for a concurrent majority, which would allow the minority to veto initiatives that it felt violated their liberty. To that purpose, Calhoun advocated for states' rights and nullification, which allowed states to declare unconstitutional federal legislation null and invalid. Along with Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, he was a member of the "Great Triumvirate" or "Immortal Trio" of Congressional leaders.

Calhoun led the Senate's pro-slavery party, opposing both total abolitionisms and attempts to limit slavery's growth into western regions, such as the Wilmot Proviso. Patrick Calhoun, Calhoun's father, influenced his son's political ideas. He was an ardent proponent of slavery, teaching his son that social position was determined not only by a devotion to the goal of democratic self-government but also by the possession of a large number of slaves. Calhoun was up in a world where slaveholding was the norm, and he found no need to challenge its morality as an adult. He also argued that slavery created in remaining whites a sense of honor that mitigated the disruptive potential of individual gain and developed the civic-mindedness that was central to the republican faith. From this perspective, the spread of slavery reduced the chance of social conflict and postponed the declension in which money became the exclusive measure of self-worth, as had occurred in New England. Calhoun was so strongly convinced that slavery was the key to the fulfillment of the American dream.