Top 5 Interesting Facts about John Caldwell Calhoun

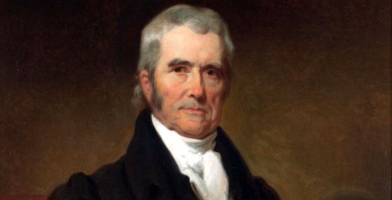

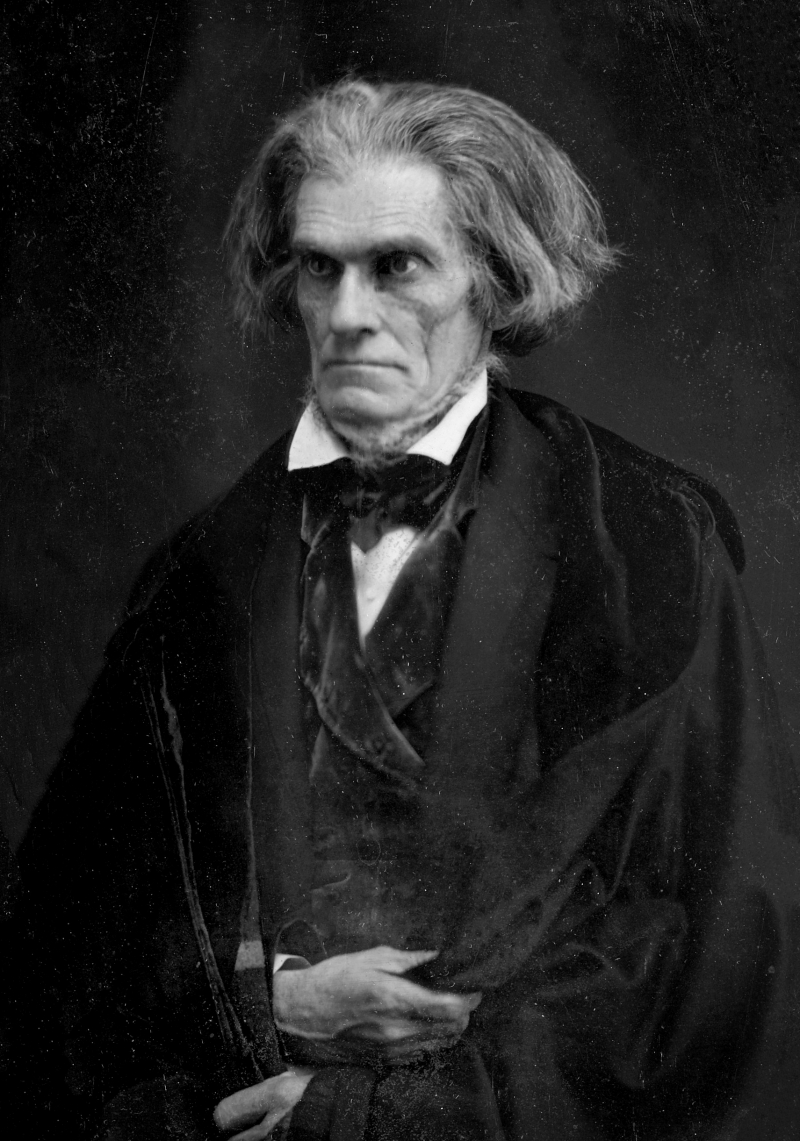

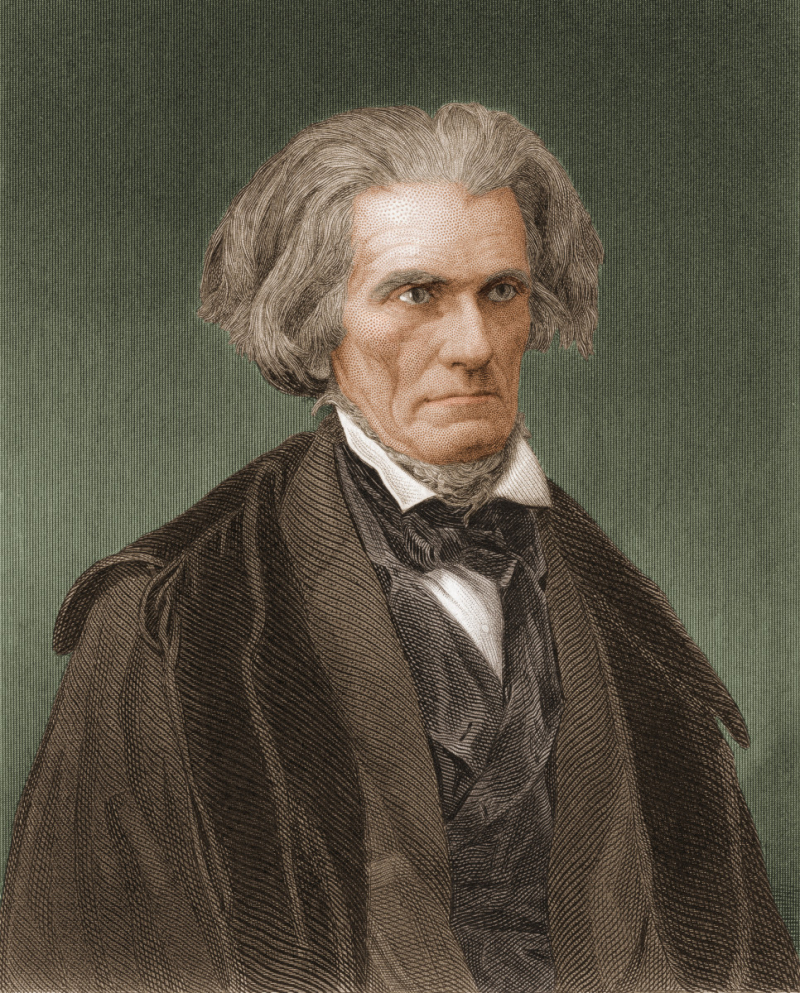

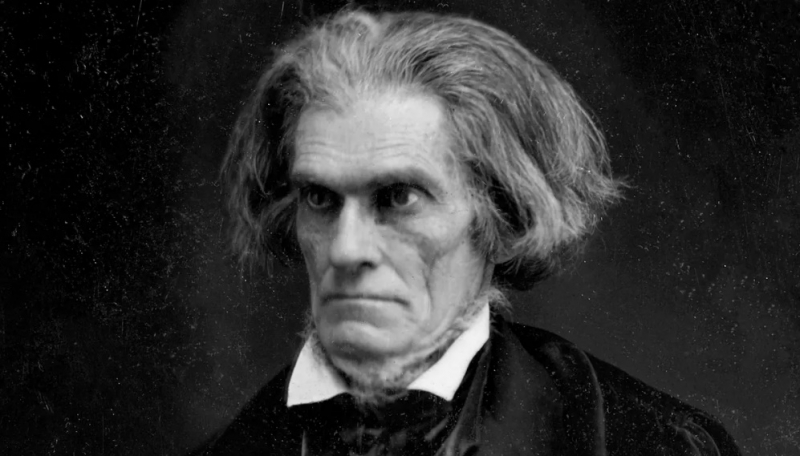

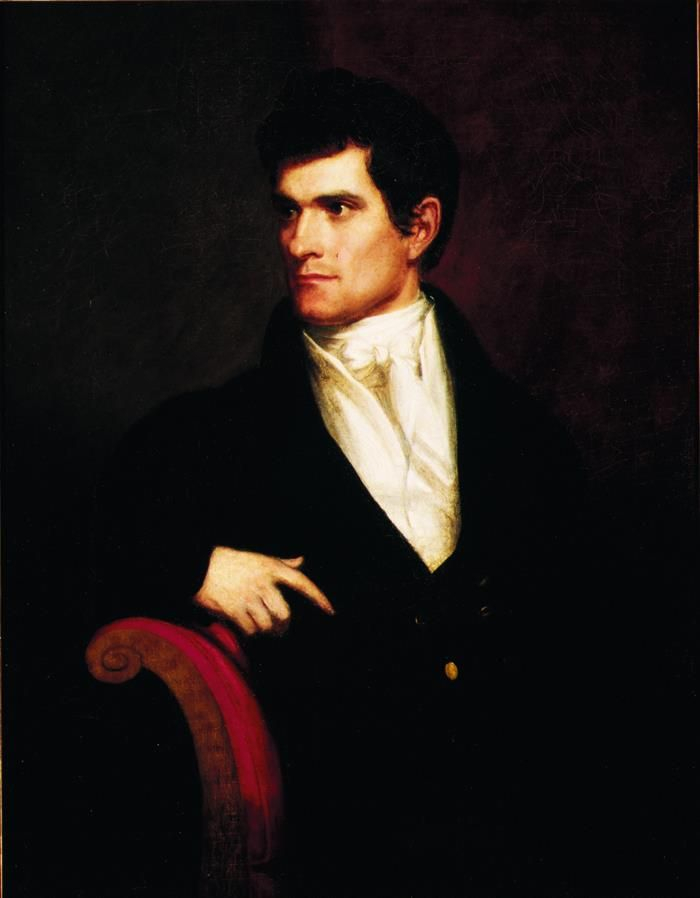

John Caldwell Calhoun was a South Carolina-born American statesman and political theorist who served as the seventh Vice President of the United States from ... read more...1825 to 1832, passionately supporting slavery and protecting the interests of the white South. He began his political career as a patriot, modernizer, and advocate for a strong national government and tariff protection. Here are the 5 interesting facts about John Caldwell Calhoun you should know.

-

One of the interesting facts about John Caldwell Calhoun is that he ran for the presidency. Calhoun was a candidate for President of the United States in the 1824 election. Andrew Jackson, Adams, Crawford, and Henry Clay were the other candidates. Calhoun did not receive the South Carolina legislature's endorsement, and his supporters in Pennsylvania decided to forsake his campaign in favor of Jackson's, instead supporting him for vice president. Other states quickly followed, and Calhoun permitted himself to be considered for vice president rather than the president. On December 1, 1824, the Electoral College unanimously elected Calhoun vice president. He obtained 182 of the 261 electoral votes cast, with the remaining votes going to five other men.

No presidential candidate earned a majority in the Electoral College, and the election was finally decided by the House of Representatives, where Adams was pronounced the winner over Crawford and Jackson, who had led Adams in both popular vote and electoral vote in the election. After Adams appointed Clay, the Speaker of the House, as Secretary of State, Jackson's supporters denounced what they saw as a "corrupt bargain" between Adams and Clay to give Adams the presidency in exchange for Clay receiving the office of Secretary of State, the holder of which had traditionally been the next president.

Photo: vi.wikipedia.org

Photo: history.com -

It is a fact that he advocated for slavery. Calhoun became known as the "cast-iron man" later in life for his staunch defense of white Southern beliefs and customs. His republicanism emphasized support for slavery and minority state rights, as exemplified by the South. In Fort Hill, South Carolina, he possessed scores of slaves. Slavery, Calhoun claimed, was a positive good that benefited both slaves and owners, rather than a necessary evil. To defend minority rights from majority control, he advocated for a concurrent majority, which would allow the minority to veto initiatives that it felt violated their liberty. To that purpose, Calhoun advocated for states' rights and nullification, which allowed states to declare unconstitutional federal legislation null and invalid. Along with Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, he was a member of the "Great Triumvirate" or "Immortal Trio" of Congressional leaders.

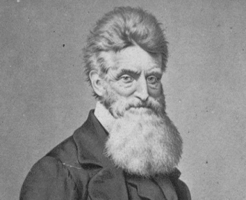

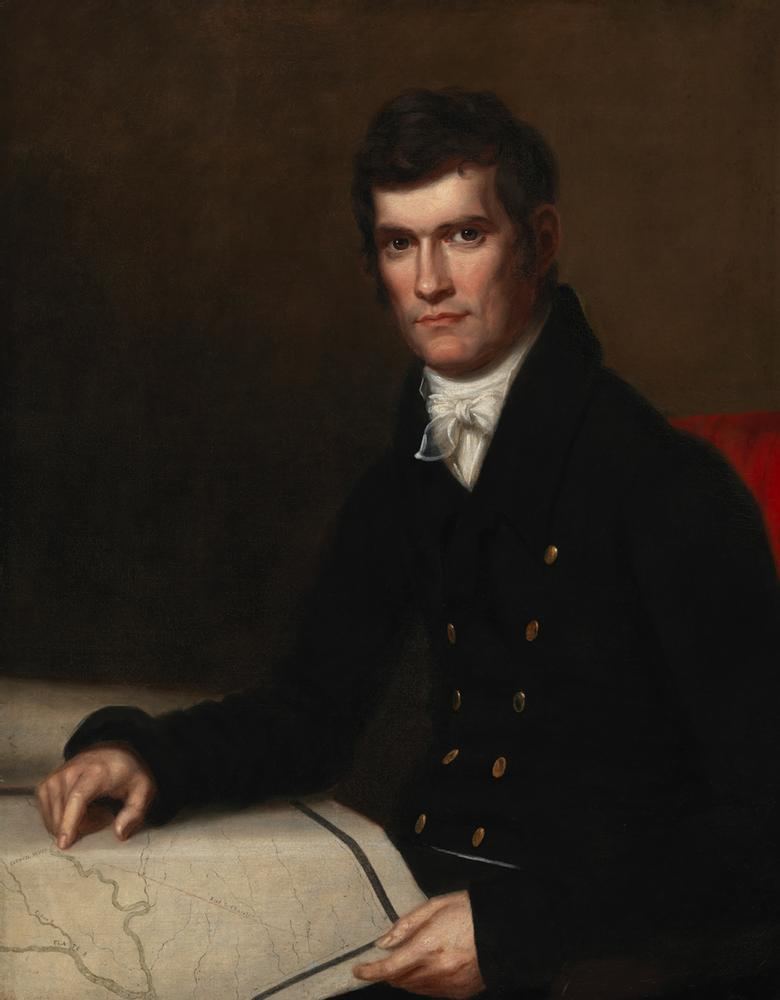

Calhoun led the Senate's pro-slavery party, opposing both total abolitionisms and attempts to limit slavery's growth into western regions, such as the Wilmot Proviso. Patrick Calhoun, Calhoun's father, influenced his son's political ideas. He was an ardent proponent of slavery, teaching his son that social position was determined not only by a devotion to the goal of democratic self-government but also by the possession of a large number of slaves. Calhoun was up in a world where slaveholding was the norm, and he found no need to challenge its morality as an adult. He also argued that slavery created in remaining whites a sense of honor that mitigated the disruptive potential of individual gain and developed the civic-mindedness that was central to the republican faith. From this perspective, the spread of slavery reduced the chance of social conflict and postponed the declension in which money became the exclusive measure of self-worth, as had occurred in New England. Calhoun was so strongly convinced that slavery was the key to the fulfillment of the American dream.

Patrick Calhoun (Calhoun's father) -Photo: en.wikipedia.org

John Calhoun -Photo: theguardian.com -

One of the interesting facts about John Caldwell Calhoun is that Calhoun was opposed to the War with Mexico. Calhoun continuously opposed the War with Mexico, believing that a larger military effort would only feed the public's worrying and growing desire for empire, inflate executive powers, and patronage, and load the republic with a ballooning debt that would upset economics and encourage speculation. Calhoun was also concerned that Southern slave owners would be barred from captured Mexican areas, as was nearly the case with the Wilmot Proviso. He contended that the conflict would result in the annexation of all of Mexico, bringing Mexicans into the country who he regarded morally and intellectually weak.

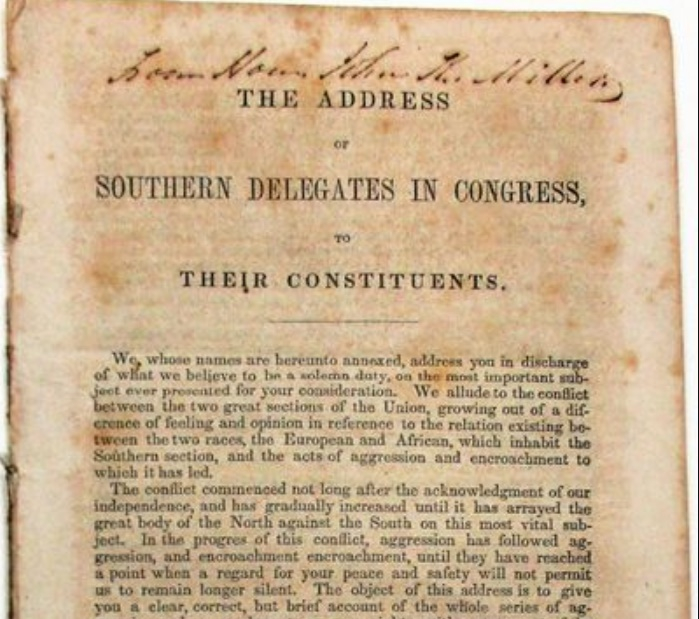

Anti-slavery Northerners saw the war as a Southern plot to expand slavery, while Calhoun saw it as a Yankee plot to destroy the South. By 1847, he had concluded that the Union was in peril from a completely corrupt party system. He argued that politicians in the North pandered to the anti-slavery vote, especially during presidential campaigns, and politicians in the slave states sacrificed Southern rights to appease the Northern wings of their parties. As a result, the important first step in any successful assertion of Southern rights has to be the abandonment of all party affiliations. Calhoun attempted to add substance to his appeal for Southern unity in 1848-49. He was instrumental in the creation and distribution of the "Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress, to Their Constituents".

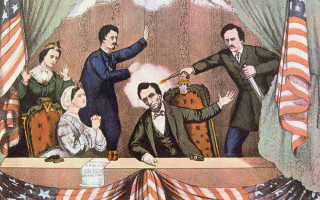

Many Southerners took his warnings seriously and regarded every political news report from the North as proof of the premeditated annihilation of the white southern way of life. The victory of Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860, a decade after Calhoun's death, led to the secession of South Carolina, followed by six other Southern states. They established the new Confederate States, which, according to Calhoun's thesis, lacked structured political parties.

The Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress, to Their Constituents -Photo: abaa.org

War with Mexico -Photo: scencyclopedia.org -

Calhoun was appointed Secretary of War on December 8, 1825, and served until 1825. During the Era of Good Feelings, he maintained his position as a leading nationalist. He proposed a comprehensive program of national infrastructure reforms that he claimed would hasten economic development. His first priority was an effective navy, including steam frigates, and his second priority was a standing army of sufficient size, as well as great permanent roads, some encouragement to manufacturers, and a system of internal taxation that would not collapse from a war-time shrinkage of maritime trade, such as customs duties.

Calhoun, a reform-minded modernizer, strove to instill centralization and efficiency in the Indian Department and the Army by erecting new coastal and frontier fortifications and building military roadways, but Congress either ignored or opposed his initiatives. Calhoun established the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1824 as a result of his dissatisfaction with congressional delay, political rivalries, and ideological differences. The bureau's tasks included managing treaty talks, schools, and trading with Indians, as well as overseeing all expenses and correspondence pertaining to Indian matters. The bureau's first director was named Thomas McKenney.

During Calhoun's service as Secretary of War, the Missouri issue erupted in December 1818, when a petition from Missouri settlers demanding entrance to the Union as a slave state arrived. In response, New York Representative James Tallmadge Jr. suggested two modifications to the bill to limit the growth of slavery into what would become the new state. These amendments sparked a fierce debate between the North and South, with some openly discussing disunion.

With their Jeffersonian vision for an economy in the federal government, the "Old Republicans" in Congress attempted to downsize the operations and budget of the War Department after the war ended in 1815. Calhoun's political struggle with Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford over the president in the 1824 election marred Calhoun's tenure as War Secretary.

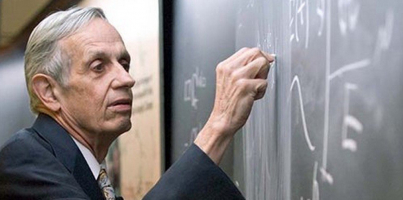

chrysler.emuseum.com

luerzersarchive.com -

One of the interesting facts about John Caldwell Calhoun is that he died of tuberculosis on March 31, 1850, at the age of 68, at the Old Brick Capitol boarding house in Washington, D.C. "The South, the poor South!" were his last words, according to legend. He was laid to rest in Charleston's St. Philip's Churchyard. During the Civil War, Calhoun's companions were anxious about the likely desecration of his grave by Federal troops and transferred his casket to a hiding place beneath the church's stairs during the night. His coffin was buried the same night in an unmarked cemetery near the church, where it stayed until 1871 when it was unearthed and returned to its original location.

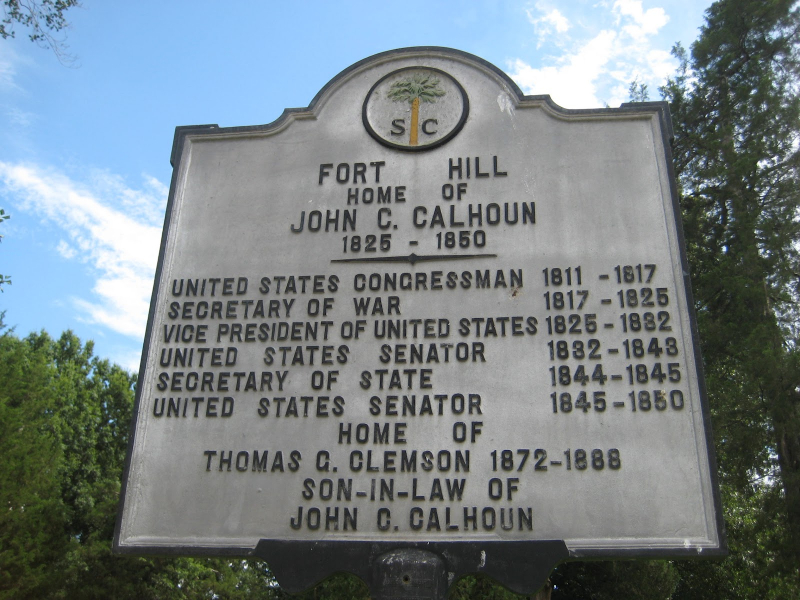

After Calhoun died, an associate recommended that Senator Thomas Hart Benton deliver a eulogy on the Senate floor in his honor. Benton, a staunch Unionist, declined, explaining: "He's not dead, sir, he's not dead. His body may be lifeless, but his teachings are alive and well." Calhoun's Fort Hill farm, which he left to his wife and daughter, is now home to Clemson University in South Carolina. They sold it and its 50 slaves to a family member. Thomas Green Clemson foreclosed on the mortgage after the owner died. He eventually left the land to the state to be used as an agricultural college named after him. Floride Calhoun died on July 25, 1866, and was buried in St. Paul's Episcopal Church Cemetery in Pendleton, South Carolina, near their children but not with her husband.

Fort Hill -Photo: clancolquhoun.blogspot.com

Grave of John C. Calhoun -Photo: pinterest.com