Lincoln actually issued the Emancipation Proclamation not once, but twice.

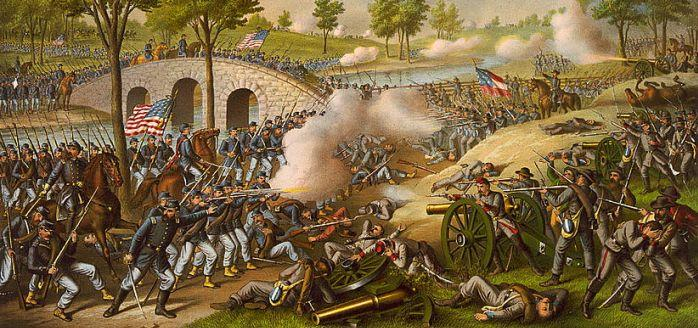

When President Abraham Lincoln felt the time had come to pursue emancipation as a “military necessity,” he read an initial draft of his Proclamation to his cabinet. However, his advisors were apathetic to the Proclamation, worried that it might be too radical. On the other hand, Secretary of State William Seward suggested that Lincoln wait to issue the Proclamation until a Union victory could prove that the federal government could enforce it. Therefore, the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation which stated that enslaved people in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free, is officially issued on September 22nd, 1862, after the Battle of Antietam in the American Evolution.

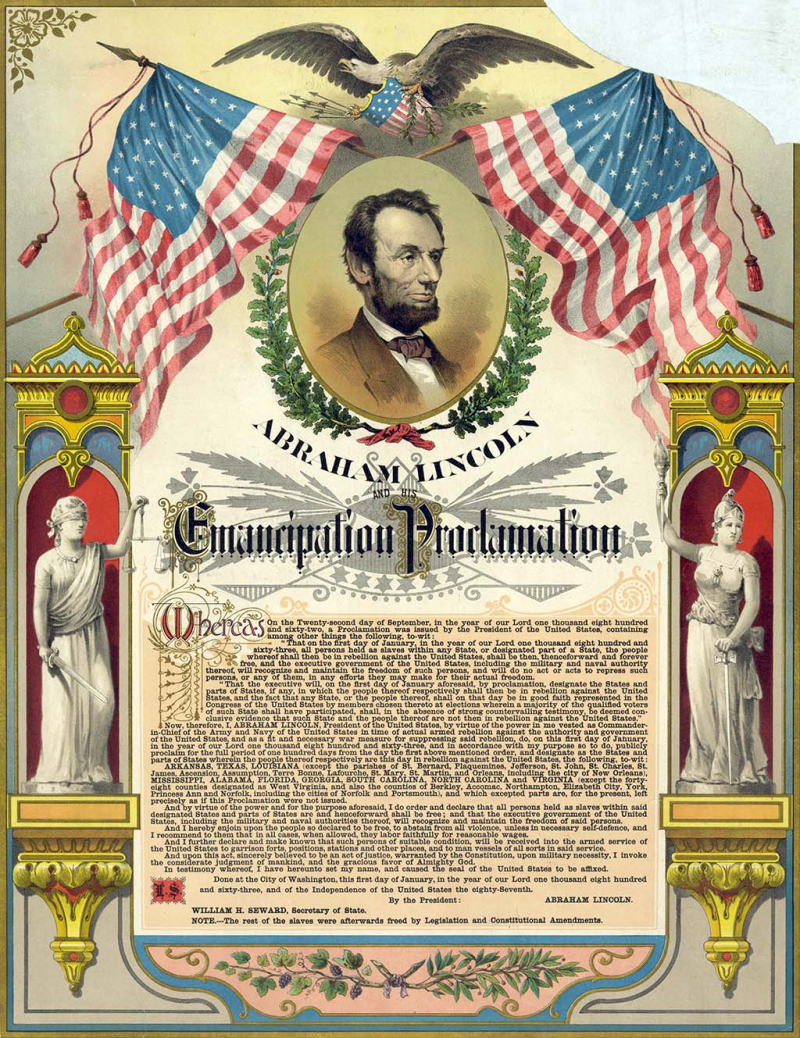

One hundred days later, When the Confederacy did not yield, Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1st, 1863. This time, the Emancipation Proclamation provided that the executive branch, including the Army and Navy, "will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons". Even though it excluded areas, not in rebellion, it still applied to more than 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country. Around 25,000 to 75,000 were immediately emancipated in those regions of the Confederacy where the US Army was already in place. It could not be enforced in the areas still in rebellion, but, as the Union army took control of Confederate regions, the Proclamation provided the legal framework for the liberation of more than three and a half million enslaved people in those regions by the end of the war.